Vintage Cameras Index Home

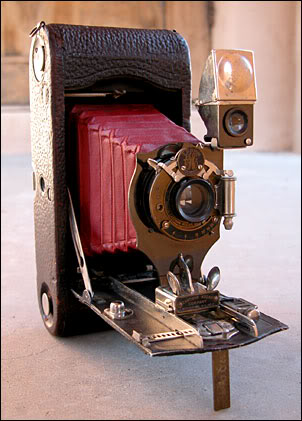

The appearance of the camera when it came out of the box was a bit daunting. Some of the leather covering had parted company with the camera, and the remainder was lifting up around the edges. There was a lot of tarnish, along with some corrosion and a small amount of rust on the metal surfaces. On closer examination, however, I could see that the lens, the shutter and the red Morrocan leather bellows were in nearly-perfect shape. This was a camera that was going to make pictures.

The dimensions of the folded camera are about 8x4x2 inches -- quite a bit larger than my other old folders which use 120 film. The larger size in this case accomodates the long-obsolete 116 size rollfilm cartridges which produced a negative that was 2-1/2 x 4-1/4 inches. In spite of its size however, the 1-A is remarkably light in weight, probably because the outer case under the leather is aluminum.

Prior to taking out the camera for a trial shoot, I did some minimal cosmetic work. These old Kodaks are pretty simple, and working on one is more akin to furniture restoration than to camera repair. I glued down the loose leather, and added a couple pieces around the bottom cut from an old leatherette notebook which had a pebbled surface similar to that on the camera. Some rust remover and Flitz polish considerably improved the appearance of the bright metal parts. The front and rear lens groups were easily removed for cleaning. The mirror in the swiveling reflex viewfinder was beyond cleaning, so I cut a replacement from a junker Polaroid; that gave me quite a brilliant view.

In order to be able to shoot still-available 120-size film in the 1-A, I nipped the ends off a couple yellow plastic drywall screw anchors and fitted them over the right-hand film holding spindles. That moves the film spools over to the left side leaving a small gap on the right, but it turned out to be minimal, and the three-sided support given to the film seemed pretty good. I replaced the missing red window in the camera's back, but I taped it during use as the gap on the right of the film chamber would let in too much light, and the numerals on the 120 film backing were of no use in any case.

The very old Kodaks are interesting partly because camera designers in those days were still experimenting with basic functions and features. Like a lot of the old Kodak cameras, the 1-A used the Universal System (U.S.) for designating aperture sizes. That system is easily translated to the current f-stop system if one remembers that f-16 is the same in both systems, and going up or down incrementally halves or doubles exposure. Thus, while the aperture settings on the 1-A indicate a range of 4 to 128, the actual f-stop values are f8 to f45.

The 1-A shutter has no markings to indicate its type, but the silky smooth action makes it likely that it is the ballbearing type. The smoothness is a real plus in this case because there is no provision for a standard cable release; speeds include T,B and 25-100. There is a metal tube which would connect to a pneumatic bulb release, but I did not get one with the camera. Another unusual feature of the shutter is an exposure counter on the shutter's front which counts off the exposures from 1 to 12. The rotating cylinder with peg stops for adjusting focus gave way in later models to a continuous screw adjustment.

Correct frame spacing when using 120 film in the 1-A depends on carefully counting advance knob rotations. Getting the film well started and giving eight complete rotations of the advance got me to the right starting point on the film for the fist exposure. I thought I had the system in hand after that with around two 360-degree rotations per frame, but I ended up with four widely spaced frames on the roll rather than the six I expected. I'm not sure what happened -- probably just a miscalculation on my part. In any case, five or six frames per roll in a semi-panoramic format is certainly possible.

I was pleased with the results from the test roll. There were no light leaks through the back or the bellows. The focus and shutter seemed right on. All the moving parts worked very smoothly. In short, the camera seemed to be performing very much as intended nearly a century ago.

The Rapid Rectilinear lens produced a little less sharpness than I am used to from same lens design in the slightly newer No. 2 Brownie folder. It is possible that the design is better suited to the smaller 6x9 format. However, there were really too many variables to make any summary judgments.

All four shots were hand-held. The film was certainly not as flat as it might be if it had spanned the full width of the 116 frame. A much better comparison would be obtained from using 70mm film with original or recreated 116 paper backing. The film went very loosely onto the take-up spool; the fit on the supply side was just not close enough to provide adequate tension. With the original film format, or maybe some foam padding on the supply side, the streaks along the frame edges would have disappeared. It's a grand old camera.

For a better way to adapt a 116-format camera to use 120 rollfilm,

please go to Page 2 ...

Vintage Cameras Index Home

© mike connealy

© mike connealy