This is a Minolta Hi-Matic 7s rangefinder camera built by Minolta Camera K.K around 1966. The Hi-Matic 7s is an evolution of the original Hi-Matic from 1962 which was one of the very first Japanese cameras with full auto exposure. The 7s added several important features like full manual control, a faster lens, flash hot shoe, and a more advanced metering system. It was one of the more desirable Japanese rangefinders of the 1960s and sold very well. As a result, this camera still enjoys a positive reputation among collectors and photographers alike. It is a large body camera that compares in size to the Yashica Electro, Canonet QL17 and QL19, and Konica Auto S2, but stands apart from those models because of its flexibility with full manual and automatic control over shutter speed and aperture.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lenses: Rokkor-PF 45mm f/1.8 coated 6-elements

Focus: Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Seiko-LA Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/4 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Lens Mounted Dual CdS Contrast Light Compensator system (CLC)

Battery: PX625 1.35v Mercury

Flash Mount: Hotshoe

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_hi-matic_7s.pdf

History

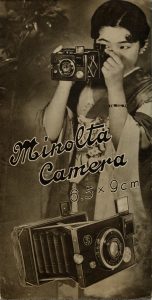

Minolta was a Japanese company founded in 1928 by Kazuo Tashima in Osaka, Japan. Tashima enlisted the help of German camera technicians Billy Neumann and Willy Heilemann to help him design Japanese made cameras, but utilizing German expertise. The company was originally known as Nichi-Doku Shashinki Shōten which translates to “Japanese-German Camera Shop”. In 1929, Nichi-Doku released its first camera, a folding 6 x 4.5 cm camera known as the Nifcarette which was inspired by similar German folding cameras of the time.

In 1931, the company changed its name to Molta Gōshi-Gaisha. The word “Molta” is an acronym of a German translation meaning “Mechanism, Optics and Lenses by TAshima”. Shortly after this time, both Billy Neumann and Willy Heilemann left the company to form their own company simply called Neumann & Heilemann.

In 1933, Molta Gōshi-Gaisha applied for a trademark for the name Minolta which would be used as a brand name for their forthcoming cameras. After World War II, much of the information regarding the history of the company was lost or destroyed, so it’s hard to know for certain if Minolta was also an acronym like Molta. Some sources say that Minolta stood for “Mechanism, INstruments, Optics and Lenses by TAshima”, but others state that Minolta is taken from the Japanese term “Minoru ta” (稔る田) which means “ripening rice fields”. Ripening rice fields are commonly used as symbolism in Japanese culture for signs of health and prosperity. In addition “Minoru ta” is pronounced exactly the same as the name “Minolta”.

Throughout the 1930s, the company saw great success in Japan and started releasing other lines of cameras and photographic equipment. In 1937, the company changed its name once again to Chiyoda Kōgaku Seikō K.K. which is often abbreviated as “Chiyoko” and released its first Twin Lens Reflex known as the Minolta-Flex.

In 1940, Chiyoko introduced the Rokkor line of optical lenses for military use only. During the early part of World War II, Chiyoko produced cameras both for military and civilian use, but in 1943 stopped all civilian production. Chiyoko was heavily involved in the Japanese war effort, but by the end of the war, 3 out of the company’s 6 factories were destroyed by US bombings.

In 1946, Chiyoko resumed manufacturing of consumer cameras and optical equipment and continued to expand its line of cameras. In 1947, a highly successful line of “Leica-inspired” 35mm rangefinder cameras known as the Minolta 35 was released. The Minolta 35 was the first mass produced 35mm rangefinder built with Leica specifications. It sold very well and was in regular production until the early 1960s. One unique aspect of most Minolta 35s that although they used standard 35mm film, it produced negatives that were 24mm x 32mm, compared to the international standard of 24mm x 36mm. This gave exposed images from the Minolta a more square look, and because the negatives used less space on the roll of film, you would get a few extra exposures per roll. A standard 36 exposure roll of film would yield 40 exposures.

The Minolta 35 would receive 8 revisions throughout it’s 12 year production run, and only the very last revision, the Minolta-35 Model IIB would shoot normal 24mm x 36mm exposures.

By the time the Minolta 35 had been in production for a decade, competition from other Japanese camera makers was fierce and Minolta knew they would have to come up with an all new design to continue to attract new customers. In 1962, Minolta would release a brand new 35mm rangefinder called the Minolta Hi-Matic. This new camera would be the company’s first with a selenium cell light meter and also the first with full automatic exposure. The camera would gain further fame when a variant of it was taken into space by astronaut John Glenn aboard Friendship 7.

The Minolta Hi-Matic featured a very sharp Rokkor 45mm f/2.8 or f/2 lens and a very accurate rangefinder. Unlike later Hi-Matics, this was a completely automatic camera that required a battery to operate. There was no way to control the camera manually.

Minolta would quickly update the camera and in 1963 would release the Hi-Matic 7, featuring a faster 45mm f/1.8 lens, an improved CdS exposure meter, and the ability to control both shutter speed and aperture manually.

The Minolta Hi-Matic was once again updated in 1966 with two new models, the Hi-Matic 7s and Hi-Matic 9. The 7s had an all new metering system called the Contrast Light Compensator system, or CLC for short. This system moved the CdS meter to the lens itself, above the front element, but within the filter ring. The CLC system had dual CdS meters in series that claimed to be more accurate in high-contrast lighting situations. Being inside of the filter ring also had the benefit of maintaining accurate metering if a lens filter is installed. The 7s also featured a new flash hot shoe instead of the cold shoe from the earlier model. The Hi-Matic 9 had all of the improvements of the 7s, but with a faster f/1.7 lens, a wider range of shutter speeds and something called the “Easy Flash” system which was designed to simplify flash photography.

During the 1960s, Minolta’s Hi-Matic series of rangefinders sold extremely well and were very highly regarded by photographers all over the world for their great build quality, ease of use, excellent lens, and modern features. Although I was unable to find any information regarding production numbers or original price, the overwhelming supply of used examples online suggests that these were in high demand back then, and in good working order still fetch reasonably high prices on eBay.

As the 1960s neared it’s end, the market for high-spec rangefinders was disappearing in favor of Single Lens Reflex cameras. Like other Japanese companies such as Canon and Yashica, the need to reduce the size and the price of their models required Minolta to release more compact and also less featured models. Throughout the 1970s, there were no less than 10 different variants of the Hi-Matic, and with only one exception, all were less featured than the 7s and 9 models. That one exception was the Hi-Matic 7sII from 1977. It featured a fast f/1.7 lens, shutter priority auto exposure, manual control, and nearly all of the features of the Hi-Matic 9, but in a much smaller package.

The last Hi-Matic models from the 1980s were plastic bodied point and shoot cameras with features like auto focus and electronic flashes, certainly having little in common to their well built, metal bodied, and much more advanced ancestors.

Because of their long run and variety of models, not all Hi-Matics share the same level of desirability among collectors. The Hi-Matic 7sII is certainly the most desirable because it represents everything that was great about the older models, but in a much smaller package. For those who don’t mind a larger and heavier camera, the Hi-Matic 7s and 9 are still very desirable too, and in working condition are capable of wonderful shots today. These cameras compare favorably to Canonet, Yashica, and Konica fixed-lens rangefinders of the era. While this review concentrates on the Hi-Matic 7s, you really can’t go wrong with any of these cameras as they all represent the very best of Japanese camera technology.

My Thoughts

When I reviewed the AGFA Karat 36, I made a statement saying that I could summarize up my thoughts on the camera by saying two words, “German Rangefinder”. This time, I just need to replace “German” with “Japanese” and my sentiments are the same. The only difference is it took the Japanese a little longer to nail the formula of an excellent rangefinder. By the 1960s, pretty much every rangefinder being made in Japan was of very high quality, and the Minolta Hi-Matic 7s is no exception.

I talk repeatedly about my infatuation with the Yashica Electro, and while my adoration for that camera will likely never cease, on paper the Electro is an inferior camera to this Hi-Matic. Even the Konica Auto S2 which is another great 1960s full-bodied Japanese rangefinder, falls ever so slightly short to the Hi-Matic in the build quality department. I must be very lucky that I keep getting these 50+ year old cameras in great working condition and am able to shoot with them without needing to do much work on them. As a matter of fact, the only 60s to early 70s Japanese rangefinders I ever had to do any amount of in-depth work is on the Canonet rangefinders, which is funny, because usually the Canonets are often cited as the best examples of 60s Japanese rangefinders.

When I came across this Hi-Matic, it was in a box of other cameras that I had picked up at an estate sale. I wasn’t even looking for a Hi-Matic and felt it was too similar to other cameras in my collection for me to have any interest and I figured I would just flip it. As often happens, when I picked up the camera and started playing with it, it’s appeal began to reveal itself. The camera takes a PX625 battery, so I put one in to test the meter, and to my surprise it fired right up. I had no idea if it was accurate, but judging by the generally excellent condition of the camera, I had a good feeling it would be, so I threw in a roll of film and went shooting. I literally didn’t have to do anything to this camera, not even replace the light seals.

While shooting with the camera, it’s size is definitely something that prevents it from being pocketable, but despite it’s large size, everything about the camera is well balanced. The controls are exactly where you expect them to be, the camera is neither lens heavy nor body heavy. If this were a sports car, I’d be saying things like it has a 50 – 50 weight balance. I prefer the all metal wind lever to the plastic tipped one on the Yashica Electro, and the build quality seems higher than that of the Konica Auto S2, plus the aperture and shutter speed rings aren’t quite as narrow as they are on the Konica.

If I was forced to come up with one incredibly minor nitpick, I would say that Minolta’s decision to display EV values in the viewfinder instead of shutter speed was a curious decision. If you want to shoot this camera manually, but still use it’s meter, you have to translate the EV value seen in the viewfinder to that of whats displayed on the ring of the lens. I don’t know that I would ever use this camera this way. I would either just leave it fully automatic or completely manual, but not in between. But like I said, this is truly a minor issue that in no way detracts from my overall opinion of this camera.

My Results

The Hi-Matic 7s has a very positive reputation and having first hand experience with several of it’s direct competitors, the bar was set pretty high. Unlike the Yashica Electro and my Konica Auto S2 where I had to make some exposure decisions on my own, I let the Minolta do it’s own thing and left it in fully automatic mode throughout the entire roll. I wanted to put the CLC metering system to the test. This camera is supposed to be really good, lets see it prove itself. I did this entire roll without any type of service whatsoever. I didn’t even change the light seals in the film compartment.

Yeah, I think the Minolta proved itself. While there were about 6 interior shots on this roll that were all out of focus, I have to blame myself for that, because the rest of the roll was spot on. The meter nailed the exposure…every…single…time, even in the blurry indoor photos I am not sharing. The only fault I had with any of the pictures was truly my own.

Well lit contrasty scenes were handled with ease, overcast shots of the crocuses and the little boy on the bicycle were handled exactly as they should. The dark shadows of the train wheels show tremendous detail. There is no vignetting in any of the shots, and the entire frame is sharp from center to corner.

This camera was designed for a 1.35v mercury battery and I used a PX625 1.5v silver oxide battery which sometimes can throw off old meters because of the increased voltage, but not here. Either the CLC meter is so good, it was able to function at the higher voltage, or the Hi-Matic has some kind of voltage correction circuit. In either case, using a battery this camera wasn’t designed for wasn’t even a problem for it.

Color me impressed. As much as I love the Yashica Electro, I will admit the “over” and “under” lights don’t always work for every situation, and the wobbly lens on the Konica makes it feel like a cheaper camera than it really is. Canonet cameras can be wonderful too, but I have never seen one that didn’t require quite a bit of service to restore functionality. So, could this be my favorite Japanese rangefinder? I think it might. Time will tell, I mean after all, I don’t have an Olympus 35 yet!

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

It gets really difficult to come up with new things to say about 1960s Japanese rangefinders because there are already so many great options, but I have to say that I think the Minolta Hi-Matic 7s could be the best of them all. It has an extremely reliable meter that handles 1.5v volt batteries without any perceived exposure errors, it has a bright and glorious viewfinder that is incredibly easy to use, an amazingly sharp lens, a hot shoe, full program auto exposure, but also offers complete manual control if you so choose. I can come up with a small list of complaints about the Yashica Electro, Konica Auto S2, and Canonet rangefinders, but not this one. This is an amazing camera that I cannot say enough good things about. If it’s not obvious yet, I wholeheartedly recommend anyone reading this review check one of these out. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for being one of the best examples of 1960s Japanese rangefinder design | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_Hi-Matic_7s

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Minolta_Hi-Matic_7

http://www.jwhubbers.nl/mug/HiMatic2.html#anchor98412

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=1044

https://rangefinder-cameras.com/minolta-hi-matic-7s-1966/

Just wanted you to know how much I enjoyed your article on the Minolta Hematic 7s. About a thousand years ago I was employed as a camera repairman at the Minolta service center in Lincolnwood (Chicago), Il. Each technician had their model specialties and mine was the HiMatics, mostly the 7 and 7s. I loved that camera and used it at that time at home. You might be interested to know that there was a black variant of the 7s, just a different top and bottom cover and winding lever in black. But very cool looking, I modified my own to be black. Thanks for the article, well done!

Hi Tom, not sure if you’ll see this. But I wanted to ask some questions about the Minolta 7s. I was just given one and I am unsure if works without batteries on Automatic. I put an MR-9 battery adapter in it with a 386 oxide cell battery as suggested due to the original battery no longer being available. I don’t see that it’s doing anything so was curious if I should just leave it as a display piece or try run a roll of film through it.

Hi Mike, I came upon this review recently and really enjoy your style of writing. I have posted a link to this page on the Minolta Collectors group on Facebook and also dropped a comment here, https://mikeeckman.com/2015/03/minolta-xg7-1977/

Here’s a link to a Flickr album about my black model 7s https://flic.kr/s/aHskq8i6nH