Screw Mount Leica II and IIIs were the most copied camera design in history, perhaps even the most copied THING in history. While counterfeit versions of Coach handbags, Rolex watches, and Nike shoes have been extremely common for decades, what makes Leica copies unique is that unlike most other luxury brands that are copied, making your own Leica is perfectly legal.

The patents for the Leica, it’s shutter, and lens mount were invalidated after World War II, meaning that any company that wanted to take Oskar Barnack’s design and make their own version were free to do so without any chance of legal recourse. About the only thing you couldn’t do is use the Leica logo or claim it to be a Leica, so as long as you came up with your own name, you were in the clear.

You don’t have to be collecting cameras for long to come across Soviet Zorkis or FEDs who took the original design and simplified it, or some of the more well known Japanese copies made by Canon, and other high profile camera makers. On the less common front were Leica copies made in the United States by Kardon, in England by Reid, and in China by Shanghai.

Of all the countries that made these copies, Japan had far and above the most. But how many were there? More seasoned collectors know about the Nicca and Leotax Leica copies, but did you know there were more….a lot more?!

When I started this article, my intent was to share with you five Japanese Leica copies that you might not have heard about, but as I researched each one, I discovered an interesting correlation between them all that links them all back to a single person. Before I get to that though, we should start at the very beginning.

The history of almost every Japanese made interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder camera comes back to Seiki Kogaku, the company that eventually became Canon. The story goes, that in the 1930s, a small optical shop was founded to produce the Kwanon, Japan’s first 35mm camera, a close, but not identical copy of the Leica II.

The Kwanon never made it past the prototype stage, but later evolved into a new camera called the Canon. Many of the first Canon cameras were distributed by a Japanese company called Omiya, who used the brand name “Hansa” on many of their products, including the Canon, therefore calling many of these early cameras, “Hansa Canons”.

Canon saw moderate success prior to the war, but around 1940, a Seiki Kogaku employee named Kumagai Genji left to form his own company called Kogaku Seiki. Kogaku Seiki was originally a service center for Seiki Kogaku, but in 1940 began working on it’s own camera, which would eventually be called the Nippon.

The Nippon was a closer copy to the Leica and lacked much of the distinctness of the Canons. Eventually, the Nippon cameras were rebranded as Nicca, and later, the entire company took the name as well.

Around 1948, Kumagai Genji would leave Nicca along with several other Nicca employees and start a series of freelance ventures with which he was linked to who made several very similar Nicca-like cameras.

Jeicy

One of the first cameras credited to Kumagai Genji is the Jeicy, only two of which are known to exist. The origins of this camera are not well known, but the most common story is that Kumagai Genji most certainly built these cameras himself using his knowledge of the Nicca and Leica. While there’s no proof that the Jeicy used Nicca parts, it is possible that some of the same tooling was used.

The oldest, and most well known example has serial number 21459 and is very similar to a Leica IIIc, with the most notable exceptions being it’s hinged back and unique film reminder dial. The rest of the camera is the same, from the position and spacing of the viewfinder and rangefinder windows, to the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, to the shutter speed, film advance, and rewind knobs.

A later example, which showed up around 1970, reportedly was in Kumagai Genji’s personal collection but differed from the earlier example by having a detachable, instead of hinged back. This version had serial number 52049 and looks much newer than the previous example, possibly being an entirely different camera altogether.

Exactly why or when the Jeicy cameras were made is unclear, but considering Kumagai Genji’s influence on many other companies, a reasonable guess would be it was either a practice model, or perhaps a proof of concept that he used to gain additional funding to build other cameras. If the Jeicy was built as a means to gain additional funding, it stands to reason that they were likely built after leaving Nicca in 1948. If so, the Jeicy would be the earliest of the cameras mentioned in this article.

Edit (6/27/2022): After publishing this article, camera collector Jo Geier contacted me with more images of the Jeicy camera. The gallery below contain all images used by permission from him.

Melcon

Kumagai Genji’s departure from Nicca in 1948 is well documented, but he was not the only person to leave the company with aspirations of building all new Leica copies.

In the early 1950s, probably 1951-52, at least one other former Nicca employee formed a new company called Meguro Kōgaku Kōgyō to produce another Leica-inspired 35mm screw mount rangefinder. Who exactly started Meguro is not clear but we definitely know the company’s roots date back to Nicca. Any link to Kumagai Genji is just speculation, but another Nicca employee named Yashima Shōhei had ties to the company, so it might have been him too.

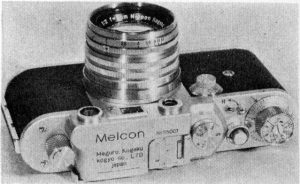

Regardless of who started Meguro, the company did exist, and began working on their new camera which they would call the Melcon. When the camera made it’s debut in 1955, the Melcon looked a lot like other Leica copies. The biggest difference was that it had a hinged back, but other changes were that it had a fixed take up spool, a different arrangement of viewfinder windows, and a top shutter speed of 1/500. As was very typical of most Leica Thread Mount cameras made in Japan at the time, the Melcon was usually sold with Nikkor lenses produced by Nippon Kogaku.

The Melcon was sold only in Japan and was distributed by Hinomaruya, the same company that also distributed Nicca, further tying the two companies together. The ad to the right suggests a retail price with a Nikkor HC 50mm f/2 lens of ¥48,000 which wasn’t cheap, but was a modest price compared to that of a real Leica.

The Melcon offered a few improvements and simplifications from the original Leica, which should have made it more appealing, but a problem with distribution and a lack of brand awareness meant it sold poorly.

In 1957, perhaps as a last ditch effort to sell more cameras, a functionally similar, but cosmetically different model called the Melcon II was released which included styling that was similar to Nippon Kogaku’s Nikon S2. The camera retained the same 39mm Leica Thread Mount, top 1/500 shutter speed and hinged back, however. The Melcon II was produced for less than a year, before the company went out of business.

Ichicon-35 and Honor 35/S1

Perhaps solving the mystery of Kumagai Genji’s Jeicy prototype, in a 1970 interview, Kumagai Genji claimed that he brought a prototype camera to Daiichi Kōgaku K.K., makers of the successful line of Waltax medium format folding cameras. Daiichi had just recently changed names from Okada Kōgaku Seiki K.K., the name it used since before the war.

Apart from confirming he had brought a prototype to Daiichi, exactly what happened next is not clear. Perhaps Daiichi agreed to build Kumagai Genji’s Jeicy camera with his cooperation, or perhaps Kumagai Genji simply sold them the design to be produced later, but whatever the exact nature of Kumagai Genji’s meeting was with Daiichi, it happened at a very bad time as the company was already going through financial troubles which resulted in bankruptcy in 1954.

Before that happened however, a prototype called the Ichicon-35 was produced which shared a strong resemblance to the Jeicy prototype, further linking the two cameras together. Only a single Ichion-35 is known to exist today, although more could have been built. A rumor exists that another prototype was either built or planned to be built which would have been called the Zenobia 35. The name Zenobia was used by Daiichi in a line of folding 4.5cm x 6cm cameras, and would later become the company’s name after their reorganization in 1957. No surviving examples or photographs of a Zenobia 35 Leica copy have ever been found, however.

After the bankruptcy and subsequent rebirth of Daiichi/Zenobia, plans to build a 35mm Leica rangefinder copy were sold to a new company called Mejiro Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. who was created specifically to build the camera. Exactly who created and operated the company is not clear, but at least one source suggests it was a man named Yamashita Kamenosuke who worked for Meguro, makers of the Melcon camera.

The new camera, now called the Honor was very similar to the Ichicon-35 prototype, which itself was very similar to the original Jeicy prototype. The exact name of the camera varied depending on publication, some referring to it as the Honor 35, and others as the Honor 35 S1. Later versions of the camera were officially called the Honor S1, so whether or not that was it’s official name from the start, or if it was adopted later, is unclear. The Honor was built by Mejiro, but distributed by yet another Japanese company called Zuihō Kōgaku Seiki, who were makers of binoculars and other optical measuring instruments.

Many Honor S1 cameras are found with collapsible 50mm f/3.5 Konishiroku Hexar lenses, but considering the large market of Japanese screw mount lenses of the era, can be found with Nippon Kogaku Nikkor, Leotax, and Topcor lenses as well. A version with a Hexanon f/1.9 lens appeared in September 1957 likely as a premium model.

In 1959, a second model, called the Honor SL was released with a rapid advance lever, a combined coincident image rangefinder, and redesigned top plate, similar to the Canon VI and L series. It is most commonly seen with a Zuiho Honor 50mm f/1.9 lens, retaining the 39mm Leica Thread Mount and top 1/500 shutter speed of other models, and appeared to have been an export only model.

The Honor SL was produced for less than a year as it never appeared in any publications from 1960 on, but the company did continue to operate still producing binoculars and other optical equipment.

Chiyoca / Chiyotax

In what sounds almost like an identical origin story to that of the Melcon, in the early 1950s, probably 1951-52, another former colleague of Kumagai Genji left Nicca to start his own company to produce…you guessed it, a Japanese Leica copy.

This new company, most commonly called Reise because it’s exact name isn’t clear, was at different times called Reise Kōgaku Kenkyūjo, Reise Optical Institute, Reise Camera Company, Ltd, or simply, Reise-Kogaku. Whatever their name, Chiyoca cameras were distributed by Chiyoda Shōkai and all cameras are engraved as being made by Chiyoca Camera Company.

Reise’s first product was a scale focus camera called the Chiyoca 35 which strongly resembles the Leica I. Apart from lacking a rangefinder, the Chiyoca 35 was a simplified camera, lacking any sort of flash synchronization or shutter speeds below 1/20. Some have been found with a shutter speed dial with a 1-20 position, but no such slow speeds exist. Most were sold with collapsible 5cm f/3.5 Konishiroku Hexar lenses.

About a year later, an updated model called the Chiyoca IF added a two post flash sync on the front of the camera, and shortly after that, the Chiyoca IIF which added a coupled rangefinder.

The exact dates the three original Chiyoca models were released vary between 1951 and 1953 depending on where you look. For sure, in 1953 the cameras appeared in various Japanese photographic publications at the time, and the length of development to produce such a model would suggest that the simpler first model likely came a year or two before that, but the 1951 date is largely speculation.

In late 1954, the name Chiyoca was changed to Chiyotax due to a copyright complaint by Chiyoda Kogaku who build the Minolta 35 Leica copy. Although Chiyoda and Chiyoca differ in spelling, the names were close enough that either Reise voluntarily changed it, or some mutual agreement was reached to sell the cameras from that point forward as the Chiyotax.

The earliest appearance of the Chiyotax name appeared around December 1954 and continued for the next couple of years as the Chiyotax IIF. An updated model, now with slow speeds called the Chiyotax IIIF appeared and was the top model. Early Chiyotax IIIF models continued to be engraved as being made by Chiyoca, but later models changed to say Reise Camera Company, Ltd for the first time acknowledging the actual manufacturer of the cameras.

This name change foreshadows a collapse of relations between Reise and Chiyoca, perhaps suggesting that Reise was on the hunt for a new distributor to help sell their cameras.

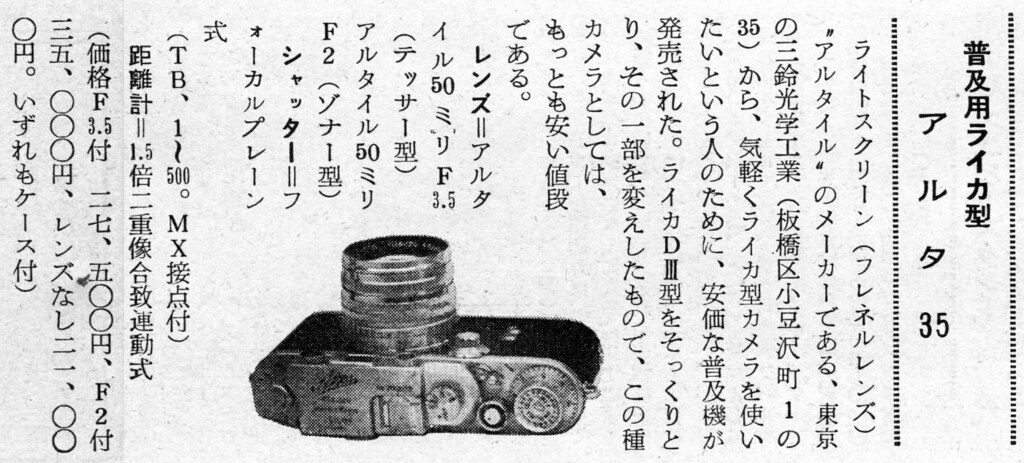

Alta

Around 1957, a camera called the Alta or Alta 35 was released by Misuzu Kōgaku Kōgyō, yet another Japanese distributor at the time. The Alta 35 was identical to the Chiyotax IIIF and is believed to be a continuation of that model, still produced by Reise after they lost their distribution agreement with Chiyoca.

Connections between Misuzu and Reise are not exactly clear, but the timeline of the last appearance of the Chiyotax IIIF and appearance of the Alta 35 suggest that either Misuzu Kōgaku arranged for an exclusive distribution of Reise cameras, or that the company absorbed Reise altogether, producing and distributing them under one name.

By the time the Alta went on sale, the popularity of Leica inspired 35mm rangefinders had started to shift to SLRs or more advanced rangefinder models. Contemporary Japanese cameras made by Canon, Leotax, Nicca/Yashica, and Minolta added new features and in most cases offered designs which significantly updated the looks of the camera. The Alta would have been seen as being outdated at the time, so the price was lowered to as little as ¥21,000 for the body only, making it the least expensive LTM Japanese camera at the time.

Alta cameras are most commonly found with Altanon lenses, most of the collapsible f/3.5 type, but some solid bodied f/2 examples exist such as in the short advertisement above. The camera continued to be advertised as late as 1959, with no significant updates from the original Chiyotax IIIF design before completely disappearing before the end of that year.

Tanack

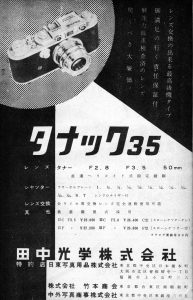

The last true Leica copy in this list is the Tanack, a series of 35mm Leica copies built from around 1952 to 1959. The Tanack was produced by Tanaka Kōgaku K.K.in Japan and was created by…you guessed it, a former employee of Nicca who has ties to Kumagai Genji. Could it be these were all the same people?

The first camera was called the Tanack 35, and like almost every other camera in this list, was a copy of the Leica III, featuring separate rangefinder and viewfinder windows, a cloth focal plane shutter with and without slow speeds, a top 1/500 speed, and using the 39mm Leica Thread Mount. The Tanack 35 is closest to the prewar Leica IIIb, suggesting that more advanced German models were either not easy to get in post war Japan for inspiration, or that these earlier models were easier to copy. Most cameras are found with a collapsible 50mm f/3.5 Tanar lens, but later versions had faster f/2.8 and f/2 lenses.

Of all the cameras on this list, the Tanack evolved the most, with the highest number of different models, all updating the specs to more closely match that of competing Japanese camera makers like Canon and Nicca. Models like the IIC, IIIC, IIF, IIIF, IIIS and IIISa were all released between 1952 and 1955 offering incremental improvements and faster lenses.

In early 1955, a new model called the Tanack IV-S was release. It was not significantly different from earlier cameras, only adding strap lugs, a film plane indicator, and revised cosmetics, but was the best selling model with the highest number built. If you were to find a Tanack camera today, there is a good chance it will be a Tanack IV-S.

Perhaps taking a cue from the Melcon II which had a resemblance to the Nikon S2, in 1957, a new model called the Tanack SD would appear that shared some similarities to the Nikon. Adding a combined coincident image rangefinder, but still using the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, the Tanack SD and Tanack IV S were sold at the same time, with a slightly higher price for the SD model.

In 1959, a new model called the Tanack V3 was released, with an entirely new die cast body with film advance lever, combined coincident image rangefinder and cleaner top plate similar to the Tanack SP, Honor SL, and Canon VI and L series. The camera’s shutter used curtains made out of a fiberglass-like material that was said to be as strong and burn resistant to the titanium curtains used by other Japanese camera makers.

Another major change was that Tanack V3 no longer used the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, instead featuring a 3 lug bayonet mount that was unique to that one camera. Only two lenses were ever made in the mount, both 5cm Tanars, one f/1.9 and the other f/2.8. A LTM to Tanack bayonet adapter was also available, allowing for full compatibility with any LTM screw mount lens available.

In the July 1959 advertisement to the right for the Tanack V3, a version including a Tanar H.C. 5cm f/1.5 lens was offered for ¥39,000, but all examples of this lens that have been found all have the LTM screw mount, rather than the V3’s bayonet. It is not clear if a bayonet version was planned but never built, or if the lens would have included the LTM adapter when it was sold.

Perhaps realizing that a low production camera with a proprietary bayonet lens mount might be a tough sell, one final model called the Tanack VP was produced which had a revised top plate with slightly larger viewfinder windows, but more significantly, retained the 39mm Leica Thread Mount instead of the bayonet mount of the V3.

The Tanack V3 was produced in very limited numbers, with less than 1500 thought to have been made. The Tanack VP is even rarer as the camera was never officially put up for sale and only a few surviving examples are known to exist. It is plausible that the VP was intended for wider production, but financial troubles which by the end of 1959 caused the company to go out of business, prevented the VP from ever officially hitting the market.

Look and Elega 35

So far, every camera mentioned in this article meets the basic qualifications of a “Leica copy” which most people seem to agree as having a 39mm Leica Thread Mount, 28.8mm flange to film distance, horizontally traveling focal plane shutter, and a control layout at least closely mimicking the original version.

What is and isn’t a Leica copy sometimes strays from that basic formula into cheaper, fixed focus, models, sometimes without focal plane shutters, without rangefinders, or even with control layouts that veer from the original Leitz layout.

These next two cameras shouldn’t be considered as Leica copies at all, but kept showing up in my research for the others in this article so I thought, ‘what the hell’. They are the Look and Elega 35, both made by Nittō Kogaku Seikō from about 1950 to 1952. Both cameras share a passing resemblance to a Leica copy with the Look featuring a coupled rangefinder and the Elega without, but beyond that are quite different.

Nittō Kogaku Seikō was founded in 1938 and produced a variety of flash and other optical related accessories before and after the war. The company’s first camera was the Look, a camera that despite a hint of Leica design and support for double perforated 35mm film, shared almost nothing in common with it.

For starters, the Look had a fixed Lunar 45mm f/3.5 lens and appeared to use some type of internal helix for focusing. A lever below the lens, or a geared dial around one rangefinder window similar to the Zeiss Contax and Nikon rangefinder could be turned to focus the lens.

Film loaded from the bottom and did not have a traditional take up spool. Instead, film transported from cassette to cassette and offered mid roll changes via a film cutting knife similar to the Exakta. Strangely, the film cutter could only be accessed after removing the bottom plate, which means it could only be used in complete darkness since doing so in light would expose the film in the camera. Film cannot be rewound back into it’s supply cassette. What appears to be a standard rewind knob on the top plate of the camera is a film tensioning knob. I am not exactly clear how this knob works as it would seem that anything that could tension film, should also be able to rewind it, but if I ever get my hands on a Look camera, I’ll be sure to let you know.

Neither camera had a traditional focal plane shutter, instead relying on a behind the lens rotary shutter with a top 1/150 speed, similar to that from the Berning Robot and Olympus Pen F SLR. One side effect of a rotary shutter is that it is impossible to cover an entire 24mm x 36mm exposure, so the Robot instead exposed square 24mm x 24mm images and the Olympus Pen F, half frame 18mm x 24mm images. I’ve found no information about the exposed image size of the Look, so I assume it’s the normal 24×36 size, although I am not sure how they managed to do that with a rotary shutter.

Edit: Before publishing this article, I found an archived Japanese language site that claims the Look had a laterally traveling metal blade focal plane shutter that was the predecessor to the Copal Square shutter. While a laterally traveling metal blade shutter would have eliminated any debate about whether the Look made 24mm x 36mm images, it introduces a few more suspicions as the Copal Square was a very advanced shutter that would not make it’s debut for at least another decade. How a predecessor to the Copal Square, even a highly simplified version one, could have been developed for such an inexpensive camera, so early on, with no evidence of it’s existence until at least 1960 when the Konica F was released, seems unlikely to me.

One final strange feature was a removable round window on the back of the camera whose purpose is not clear. At least one site I’ve read suggests it was for critical focus, but unless there was a ground glass somehow in line with the film plane, I can’t see how that would work. Even if it did, it would need to be done without any film in the camera as opening the back would expose the film. Perhaps it was for inspecting the rear element, similar to the Zeiss-Ikon Cocarette.

The Look sold in 1952 for ¥9500 which was nearly one third the price of a Japanese Leica copy and one fifth that of the real thing, making the Look an attractive option for someone wanting a 35mm rangefinder without paying a hefty price tag.

It is not clear how well the Look sold, but apparently well enough to warrant a second, simplified model called the Elega 35. Removing the coupled rangefinder and gear driven focus wheel, the Elega 35 was a scale focus camera that was operated using a lever around the perimeter of the lens. Two versions of the Elega 35 are known, one simply called the earlier and one the later version.

There are conflicting reports about the features of the Elega, some saying the lens is removable, others saying it is not. If the lens was removable, perhaps it could be used on an enlarger as no additional lenses appear to have been made for it. Another discrepancy is whether the film could be rewound or not. Like the Look whose film transport is cassette to cassette, as best as I can tell, the earlier Elega 35s use cassette to cassette, while the later ones could be rewound. One final discrepancy appears on a site which suggests the top shutter speed is 1/500, which I do not believe to be true as all images of the Elega 35 I’ve seen clearly show a top 1/200 speed. This would be a much more logical progression from the top 1/150 speed on the earlier camera.

Motoca 35

One final, non-Leica copy that can sometimes be grouped together with the cameras above was an inexpensive and simpler model called the Motoca 35, produced between 1948 and 1949 by Kashiwa Seikō. The Motoca 35 only looks like a Leica in passing similarity, but in reality the two cameras have more differences than things in common.

For starters, the construction of the Motoca is significantly lower quality than even the cheapest Japanese Leica copy. The Motoca was viewfinder only, but had a top plate mimicking that of a camera having a rangefinder. It shoots 24mm x 32mm exposures, which was common at the time for Japanese cameras, but not something any other camera here did.

According to Sugiyama, the Motoca 35 has a sector shutter with speeds ranging from 1/20 to 1/300, which is described as a fan type shutter, rather than a cloth focal plane design.

The lens mount is interchangeable and the advertisements to the left and right describe it as “Leica type”, but never actually say it takes Leica lenses suggesting it uses unique lenses specifically designed for it. Whether other focal lengths were ever made is unknown. The only lens that seems to have been available for it was an unknown 45mm f/3 lens.

None of the three ads I’ve found for the camera suggest a price, but based on the state of the Japanese camera industry in the late 1940s and the camera’s cheap construction, a price of around ¥10,000 seems likely. The camera was only produced for about a year before disappearing. It is unknown how many were made as very few are known to exist today.

Unknown Cameras

The period from the late 1940s to the mid 1950s was very chaotic in the Japanese camera industry. A huge number of companies making an even larger number of models ranging from top of the line Leica copies, to cheaply built toy cameras popped up almost overnight and disappeared almost as fast.

Most collectors are aware of the most common brands, and with the lesser known models mentioned in this article, we have a pretty good understanding of all that was available, but there is a chance that still more models were created or proposed and never finished. One-off models from companies who for one reason or another never got past the prototype stage are likely to exist with names that collectors have never seen.

In my research for this article, I came across some ads that contain no English characters and have no identifying marks telling me what I was looking at. Even using the “very good but not perfect” Google Translate could not give me a clue as to the identity of these two ads pictured here. The first ad, pictured above, is from around 1948 and shows what is clearly a spitting image of a Leica III. The rounded edges do not suggest a Canon model, and the 1948 date do not suggest any of the models credited to Kumagai Genji. Google Translate suggests a name of “Heiwado” which is probably wrong, but if not, isn’t a name I’ve ever heard mentioned as a camera maker or brand.

This second undated ad appears to show a black bodied Leica copy, or perhaps even a real Leica itself, with the words “Luxury Camera” and “Ohba Shokai” in larger letters. Was this an unknown black paint Japanese Leica copy, or simply an advertisement for imported Leicas? I have no idea.

Whatever the true story of these two mystery cameras, whether they’re Japanese or not, I can’t prove the existence of more brands, but the likelihood of there being others is still very high. Maybe some day, additional models will turn up, maybe not, but whatever happens, there are already many known, making collecting them all a difficult and probably very expensive venture.

Wonderful post , you could simply look at them and marvel at the skill of the manufacturers. Modern cameras just do not have that wow factior.

EXCELLENT!

Fantastic article, Mike – lots of research produced a catalog of history that we’ll save for future reference. Do you note the styling similarity of the Honor SL to the Nicca IIIL? They share the same clean lines.

I make a vague reference that many of the last generation of screw mount rangefinders all share a similar design. Some say the Nicca III-L looks like an M3. I don’t agree with that, but the styling is nice!

Fascinating! I’m infatuated with Japanese rangefinders even though they are a pain to use, compared to an SLR. My 2 cents anyhow

Ayh happened upon your website and ayh’m loving the content. Ayh thought ayh’d provide a few simple translations of the relevant Japanese advertisements reproduced here.

The green-colored advertisement does indeed say “Heiwado”, but ayh don’t think it’s the name of any manufacturer. Underneath the three characters making up “Heiwado” is its address, but to the left, the top row of five characters literally mean “[at] highest price purchase”, meaning that “Heiwado” buys (cameras) at the highest price. This leads me to believe that “Heidawo” was a camera store or a second-hand camera trader, especially since the diagonal hashes are really Japanese kana characters saying “Camera’s” (note possessive form). Together with “Heiwado”, this literally means “Camera’s Heiwado”, which is really “Heiwado Camera”, much like how the sign on the old Tamron corporate HQ building says “Lens’s Tamron”, or “Tamron Lenses”.

The seven characters right beneath literally “ones in the same business transactions welcome”. Again this is a very literal translation but it really means that other camera stores/traders are welcome to do business with them. Ayh think the use of a “Leica-like” camera on the top left corner isn’t meant to represent any specific Leica (or Leica copy), much like how a used car trader would use a generic car in his advertisement.

Moving on to the black-colored advertisement. The translation of “Ohba Shokai” is correct. “Shokai” means “business” (as a noun), usually something sizable with a variety of subsidiaries or areas of activity, though ayh suppose the term is used here to make “Ohba” seem bigger than it may have been. The “luxury camera” bit is better translated to “high-end camera(s)”. The interesting line in this advertisement, however, is made up of the eight characters above the “high-end camera / Ohba Shokai”. Those eight characters literally mean “imported [and] domestic cameras in stock numerous”, or “numerous imported and domestic cameras in stock”. Again, ayh think this “Ohba Shokai” is another camera store or trader.

Ayh hope this has been of some use to you and ayh appreciate greatly your fine website. Thank you!

I recently picked up a Tanack VI-S at auction and since been at a loss to understand why these cameras command the kind of prices they do. Build quality, in my opinion, is well below that of other Japanese M39 cameras. This thing has poorer build and more issues than any Nicca, Canon and Leotax cameras I’ve encountered. Even the Tanar f2 lens has bubbles in the glass! Not even my FED 1-series cameras have bad glass like that! I’m doing a teardown on this IV-S and we’ll see if I can address all these issues: sticking/non-coupling slow speed timer, rough advance, out-of-whack rangefinder glass and alignment, etc…The only good thing I can say is that the curtains are still good. Maybe back luck of the draw here, but the couple Niccas I have arrived flawless – every bit as good as a contemporary Leica.

Erik, thank you for your reply. I have been eyeing a Tanack on eBay for a while. I own a Nicca and Leotax and have been happy thus far. I am now reluctant for movers forward with the Tanack and maybe look at another option.