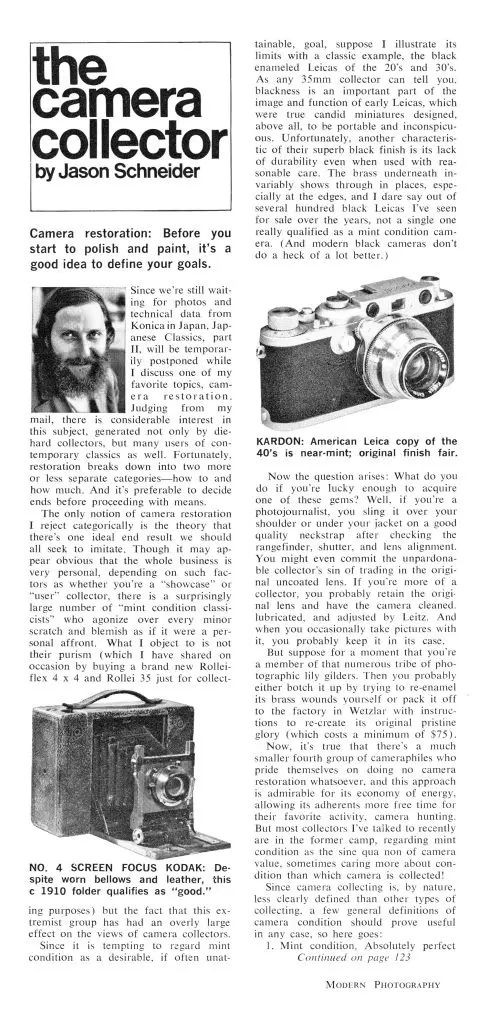

This is a “military” Kardon 35mm rangefinder camera, produced by the Premier Instrument Corp in New York City between the years 1947 and 1954. The Kardon was originally developed as an “American Leica” after imports of cameras from Germany had ceased during World War II. Charged with building the camera was the New York office of Ernst Leitz who was unable due to a lack of parts and skilled tradesmen, so the job was subcontracted out to a man named Peter Kardon who was the President of Premier Instrument. Production of the camera would not be complete until after the war was over, so both civilian and military use models were created for sale to the generic public and also used by various US government agencies.

This is a “military” Kardon 35mm rangefinder camera, produced by the Premier Instrument Corp in New York City between the years 1947 and 1954. The Kardon was originally developed as an “American Leica” after imports of cameras from Germany had ceased during World War II. Charged with building the camera was the New York office of Ernst Leitz who was unable due to a lack of parts and skilled tradesmen, so the job was subcontracted out to a man named Peter Kardon who was the President of Premier Instrument. Production of the camera would not be complete until after the war was over, so both civilian and military use models were created for sale to the generic public and also used by various US government agencies.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 1.9 inch (47mm) f/2.8 Kodak Ektar coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: M39 Kardon Mount

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder and Viewfinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Accessory Shoe, no Flash Sync

Weight: 675 grams (w/ lens), 453 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Kardon was the best attempt and closest any American camera maker ever came to matching or exceeding the quality of the Leica rangefinder. Originally built for military use and then sold to civilians, only to be modified once again for military use, the Kardon has a fascinating story that’s as interesting as any camera story I’ve ever researched. In use, the camera has a very good build quality and came with an excellent Kodak Ektar lens that produces images as good as those by any German or Japanese maker. Unlike some other Leica copies that made changes to the original formula without making the camera better, the Kardon has a few changes which I think add to the experience. These cameras are very rare, and finding one in good condition will be very difficult, but if you have an opportunity to pick one up, I definitely recommend it! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.0 | ||||||

Prologue

As I normally do when I research the history of cameras I write about, I use a variety of sources from published books, magazines, dealer catalogs and promotional materials, and in some cases, other online sources. In the case of this article for the Kardon, a huge amount of the info comes from a single source.

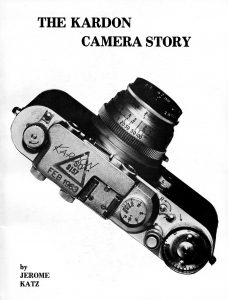

In 1975, “The Kardon Camera Story” was written by Jerome Katz as a way of telling the story of the Kardon and the people who made it. As far as I can tell, the book was only published until 1977 and has not been available since. Tracking down copies of this book was extremely difficult as many collectors I correspond with had never seen one. As of the time of this writing, there were none for sale on eBay or any other auction site, anywhere in the world.

This prologue is both to state the source of most of the research that follows, but also to thank Dan Hausman of the Ohio Camera Collector’s Society and Ohio Camera Swap who graciously loaned me his copy of the book for this article.

History

In the years before World War II, both Ernst Leitz of Wetzlar, Germany and Zeiss-Ikon of Dresden, Germany both produced two of the most well featured and highest quality 35mm cameras in the world,

For many though, the ultimate winner between the two was never in doubt. The Leica camera, originally designed by Oskar Barnack was the clear winner. Featuring a design that was easier to use, had a simpler lens mount, came with a wide selection of lenses, and was built to the highest level of quality possible, the Leica camera was sought after not only by photographers, but militaries all over the world.

In the United States, Leitz had been operating a sales office in New York since the 1890s for their microscope business, but with the success of the Leica camera, the New York office became the central sales and primary distributor for Leica cameras. Along with sales and distribution, the New York office also repaired cameras, retrofitted some models, and produced a number of accessories for the camera, so they had some production abilities as well.

By the end of the 1930s as hostilities with Germany were increasing, it became more and more difficult for the New York office to receive new product from Wetzlar, so it was clear that the Americans would need to find some other resource for a precision 35mm camera.

In 1937, Eastman Kodak took up the challenge in developing an entirely new 35mm rangefinder camera that would match or exceed the features and specifications of the Leica. While in development, Kodak’s new camera was called the Super Kodak 35, but upon it’s release in 1940, was renamed the Ektra.

The Kodak Ektra was a technological marvel, featuring Kodak’s best lenses and a brand new interchangeable bayonet lens mount. The Ektra was the first interchangeable lens camera in the world in which all all six of it’s available lenses received a hard “lumenized” coating to improve contrast, light transmission, and color accuracy. It had the widest base length rangefinder of any 35mm camera, a very accurate focal plane shutter with speeds up to 1/1000, an interchangeable magazine film back which allowed for film changes mid roll without having to rewind or cut the film, a variable focal length viewfinder, film advance lever, and a host of other new features. Although meeting the challenge of meeting or exceeding the Leica in every way, the Ektra was extremely expensive, with a civilian retail price of $300 with the Kodak Ektar 50mm f/1.9 lens, which exceeded a 1940 retail price for a Leica IIIb with Summar 50mm f/2 lens for $222.

Whether the Ektra was seen as an alternative to the Leica is debatable, but it’s development and use by the US Signal Corps suggests that Kodak’s input was valued for making a wartime camera.

In early 1942, with the United States now an official participant in the war, the New York office of Ernst Leitz was seized and placed under control of the Office of the Alien Property Custodian as companies led by wartime enemies were not allowed to continue doing business in America. Now entirely under control of the US government, Ernst Leitz New York was challenged with the task of building an “American Leica” that could both be sold here and used by the military.

According to most accounts at the time, although some of the machinery and tooling to make cameras did exist in New York, it was in such poor shape that it could not be used to make new cameras without first creating new tooling and equipment from scratch. Further adding to the challenge was that back in Germany, Leicas were still built by hand and each model required a great deal of fine tuning to get right and there simply weren’t enough skilled tradesman in the United States with the necessary experience to complete the job. The only way an American Leica could be produced, was if another company were to rise to the challenge and build it.

At the time, the only American company with the experience and manufacturing capacity to accomplish such a feat was Eastman Kodak. Kodak had proven themselves to be resourceful in building high quality cameras such as the Kodak Ektra and Bantam Special, and of course they had the experience of the Kodak AG division in Stuttgart, so why didn’t they build an America Leica?

In his book, “The Kardon Camera Story”, Jerome Katz theorizes that although Kodak probably could have done it, they didn’t want to become involved in the manufacture of a copy of someone else’s camera. Something I’ve noted many times in various reviews is that Kodak was a “film first” company, and while they also produced a number of terrific cameras, this wasn’t their primary market. Furthermore, Kodak may have seen it as competing with themselves if they were to build and sell an American Leica along with the Kodak Retina, Ektra, and other previously marketed cameras.

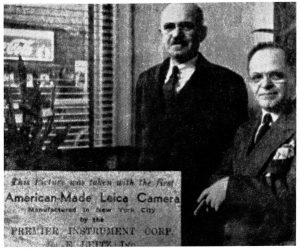

For reasons that Katz’s book does not make clear, in 1943 an Odessa, Russia (now Ukraine) born immigrant named Peter Kardon (originally Kardonsky) was approached by the US Signal Corps to create the new camera. Peter Kardon, along with his childhood friend David Bogen, operated a manufacturing company then called the Premier Tool and Instrument Company. Kardon’s previous experience is not clear, but he was regarded as an innovative and resourceful engineer, and together with Bogen, thought that with the help of the Ernst Leitz New York office, they could create the American Leica.

Kardon negotiated a contract with the US Signal Corps to produce 6000 cameras paid out on a fixed, per unit price. In the contract, whatever available dies and tooling were available at Leitz would be included as well. Upon delivery of the machinery from Leitz however, Kardon discovered that it was all in such poor shape that nothing could not be used or repaired. Kardon realized that before he could start building the camera, he would also have to manufacture the parts and tools to do it. In another twist, the initial agreement of 6000 cameras was reduced to 2000, and later again to only 750. Despite these extraordinary challenges, Kardon continued with his endeavor.

In total, over 1000 parts were created from scratch to build and assemble Kardon’s camera. This, considering that only 750 would need to be built and that the original price negotiated did not change when the order decreased from 6000 to 750, it was clear Kardon would lose a great deal of money on each camera sold.

In 1944, the New York Leitz office was able to acquire three Leica IIIa cameras which they turned over to Peter Kardon and his team, now known as Premier Instrument Corp. The cameras were given to Kardon’s son in law, Irving Gross who disassembled all three, painstakingly documenting their construction and measuring the tolerances of each part.

Upon inspection of the disassembled cameras, it was clear the amount of tweaking each Leica went through while being produced, making each model truly unique from the others. A priority for Kardon’s new camera would be to reduce the number of parts that required individual “fiddling” during assembly. Changes to internal parts from the original Leica were made so that parts could be built on an assembly line and put together without any fine tuning. This, in itself was a monumental task as it should be assumed that if the Germans couldn’t build parts with the necessary off the shelf tolerances to not need tweaking, how could Peter Kardon?

Kardon’s camera was based off the Leica IIIa from 1935. Although the Leica IIIb and IIIc had already existed by the time Kardon’s contract was signed, it is thought that the older IIIa was easier to get and simpler to reproduce than the later models which made their debuts in 1938 and 1940 respectively.

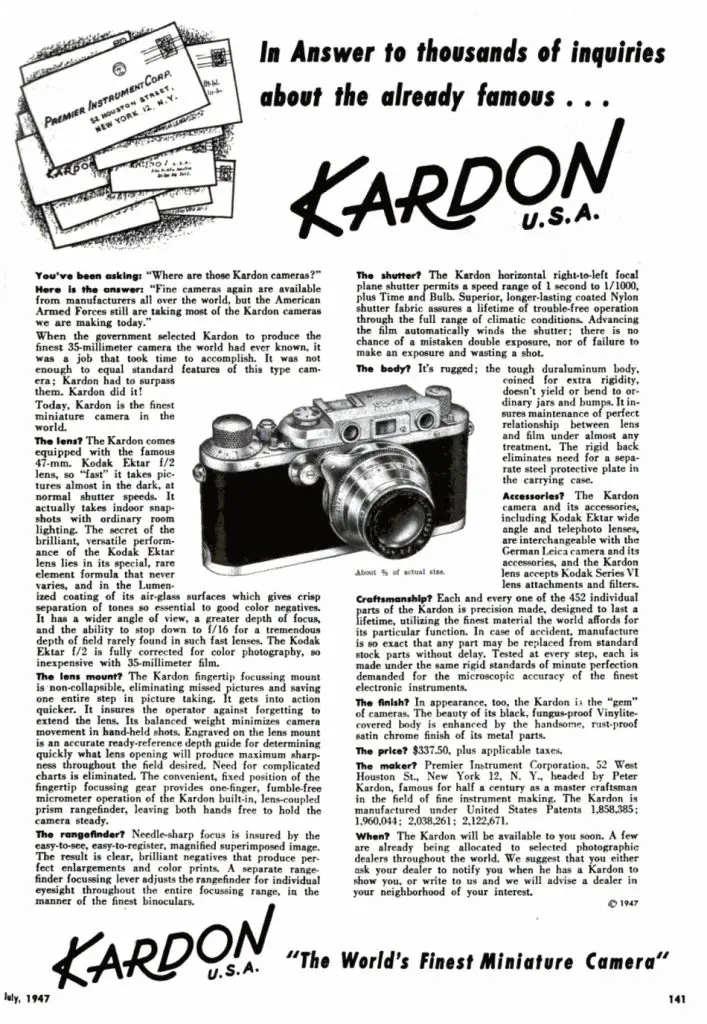

For it’s lenses, the camera used existing designs purchased from Eastman Kodak. The standard lens was the same 6-element 47mm f/2 found in Kodak’s Bantam Special. In the Bantam Special, the lens is measured as 45mm, but according to Katz, this was just a change in how the focal length was measured. Like other lenses Kodak was producing at the time, the Ektar received Kodak’s lumenized coating which helped improve light transfer making the lens effectively faster than early examples on the Bantam Special.

Although Kodak produced the lens, they did not create the focusing mount that each lens would eventually have. Upon receipt of the Ektar lenses, Kardon’s team would mount them in a focusing mount unique to the new camera. Since the camera was intended to be used by the military where the photographer would likely be wearing gloves, a wheel was added to the mount instead of the standard lever like on other Leica Thread Mount cameras. The actual mount one the camera’s body was the same 39mm screw thread as Leica cameras had allowing for interchangeability between the two cameras.

The use of “Kardon mount” on some reviews for Peter Kardon’s camera often confuses some collectors into thinking the physical lens mount was different, when in fact, it was not. In the image to the left, the Kardon camera has a Leitz Elmar 5cm f/3.5 lens mounted will full rangefinder coupling.

The first completed samples of Kardon’s new camera were completed in mid 1945, but the surrender of Japan in August of that year caused the contract between the US Signal Corps and Premier to be abruptly terminated. A settlement between Premier and the government resulted in a meager 10% of the agreed upon sale price for the cameras, but this did not take into account the high development and material cost of the tooling that had to be made to produce the camera. Peter Kardon stood to lose a huge amount of money for the time and effort he put into the American Leica.

With an almost completed camera and no one to buy it, Premier decided to try and recover some of their losses by selling a civilian version of the camera. Now officially known as the Kardon camera, the “civilian Kardon” received a shinier chrome plating on the body and lens to more closely match the look of a real Leica, along with a smaller film advance knob and shutter release that was more in line with what Japanese Leica copies had as well.

When it first went on sale, the Kardon had a suggested price for the camera and Ektar lens of $393 with actual retail prices closer to $340, which when adjusted for inflation, compare to between $4100 and $4750 today, an astronomical price for a copy of a camera that a few years prior could be purchased for half that. Despite the high price, at the time, the Kardon was the only Leica style, real or copy, that could be easily found in the US. Although Leitz never stopped producing cameras during and immediately after the war, getting German cameras imported into the United States at this time was prohibitively difficult. Japanese companies like Canon and Nicca were also producing cameras at a much lower cost, but they too were difficult to find, and the general opinion of buying a camera from unknown Japanese companies that Americans had just ended a war with was likely a tough sell for many people, making the Kardon the best option for patriotic customers looking for the best camera available, at least for a while.

In a strange twist of fate, shortly after the release of the civilian Kardon, Peter Kardon was contacted by Col. Jim Glenn of the US Air Force to build for them a camera that could withstand extreme temperatures and be used by various branches of the US military. Not at all deterred by the bill he was left with the cancellation of the original US Signal Corps contract, Kardon once again invested more time and money into further modifying his camera for what would be nicknamed the “Cold Camera”, or more simply, the military Kardon.

The requirements of this new camera would be that it would reliably function at temperatures as low as -70 degrees and as high as 150 degrees Fahrenheit. These numbers were likely chosen as they were the lowest and highest temperatures likely to be recorded in various extreme climates where the US military would operate. Other requirements of the camera were that it had to be entirely corrosion and fungus resistant, and to accommodate being used by those wearing heavy gloves.

The responsibility of meeting these requirements was given to Peter’s son, Leonard Kardon who was in charge of researching changes to the film transport mechanism, along with new glues and lubricants needed that could withstand the extreme temperatures without failing.

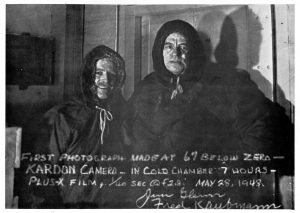

On May 28, 1948, two military Kardon cameras were delivered to Jim Glenn at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey where it’s cold weather performance was put to a test. The camera was placed in a freezing chamber for 7 hours at -67 degrees, and with some Kodak Plus-X film, exposures were successfully made of Glenn and another Premier employee proving the camera’s cold weather performance.

Now, with a civilian version of the Kardon camera on the market and a successful test of a new military Kardon, things seemed to be finally looking up for Peter Kardon, but in yet another cruel twist of fate, later that same year, Peter Kardon would develop an ulcer condition to which he would ultimately pass away from on Christmas Eve, 1948.

Satisfied with the camera, in June 1949, an order for 990 cold weather cameras was placed and delivered by July 1951. A second order for another 664 cameras was placed in June 1952 and delivered by May 1954. The relatively long amount of time between when a camera was ordered and delivered can be explained partially by the extremely thorough testing that went into the cameras before they were delivered. Every single military Kardon that was produced was extensively tested before leaving the factory. If any part of the camera failed to pass 100% of the tests, it was rejected. A detailed account of every single model, along with the results of it’s tests were kept on file at Premier should a camera ever fail and need to be returned.

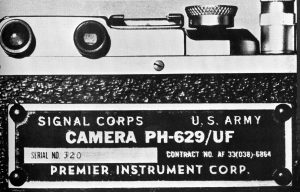

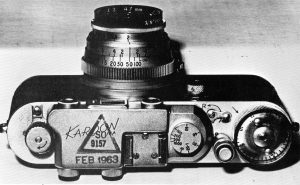

The camera, when sold to the US military was known internally as PH 629 / UF, but would still have the Kardon branding on the top plate. Spotting a military Kardon versus a civilian Kardon is very easy as most military versions have the following changes:

- A duller ‘satin’ chrome appearance on the top and bottom plates, and the Ektar lens

- Lenses have a focusing wheel near the 8 o’clock position around the lens, compared to near the 10 o’clock position for civilian cameras

- Much larger film advance knob with a recessed exposure counter inside of it

- Taller shutter release button (can be unscrewed and replaced with a Leica style shutter release cable)

- Extensions on both rear viewfinder and rangefinder eyepieces

- Small handle around the perimeter of the front slow shutter speed dial

- No serial number on the top plate

- Rectangular US Signal Corps plate on the back

A total of 1654 military Kardons were ordered and delivered, but an unknown number of spare parts were also included, suggesting a few more spare parts cameras might exist. There also exist some “hybrid” cameras that have a combination of both civilian and military parts, which could be the result of people swapping parts over the years, or perhaps Premier making some with features from both cameras.

Around the time the second order was placed, the US government had resumed the purchase and use of German Leicas and in some cases, Japanese Leica copies. This was in addition to the Kardon cameras already ordered, but by the time the final models were being delivered in May 1954, all communication between Premier and their government contact had stopped. With civilian sales all but completely gone and no further orders from the military, Premier’s factories sat idle and it’s workers laid off.

Frustrated by this lack of continued orders, in March 1955, Irving Gross wrote a letter asking why his contract had seemingly been terminated, accusing the US government of unfair competition by awarding contracts to foreign companies for their cameras, without so much as an opportunity for Premier to compete. This letter would result in a meeting at the Pentagon where Gross met with several members of the Signal Corps, the US Procurement Office and other civilian officials where his concerns were addressed.

In that meeting on May 6, 1955, Gross was informed that the military Kardon camera performed flawlessly in every assignment it was used. It met all of the requirements agreed upon and that as a supplier, his company was great to work with, and that cost was not an issue for them. The reason for the lack of new orders was that a recently de-classified report found that agents using Kardon cameras were more likely to be recognized as spies and captured by foreign governments. The presence of a camera that uniquely identified them as American, made these intelligence officials vulnerable, so it was determined that they could better blend in by using civilian cameras that would likely be found in the areas of the world in which they worked.

After that meeting, realizing that no matter how hard they might try, or how good the Kardon was, that Premier could never compete with their competition, the era of the Kardon camera was officially over. Later that year, the assembly lines where the cameras were made were taken apart, and the tools and dies used to make the cameras were destroyed, never to be used again.

In Jerome Katz’s book, he goes to great lengths to paint Peter Kardon as a genius and incredible American patriot. Here was a man that immigrated from Russia to the United States, educated himself, and through incredible amounts of hard work and determination was able to tackle a project that no one else could accomplish. He built a camera that matched, and in some cases, exceeded the original German designs, making cameras that had interchangeable parts that could be assembled without the need for custom hand fitting of precision parts. A camera that could be used in the most extreme environmental conditions on Earth and one that exceeded all demands given to it by the US military.

I won’t at all disagree with Katz’s portrayal of Kardon as his dedication and skill is impressive. Peter Kardon may have been the ultimate American patriot, and a skilled engineer, but he certainly didn’t make the best business decisions. Building an American Leica is something that Eastman Kodak didn’t want to do, something that Ernst Leitz in New York couldn’t do, and after defying all the odds stacked against him, he never made a single cent of profit from the camera. The total amount of money lost in his quest to build the Kardon is unknown, but I have to imagine it to be quite high. If that’s not enough, Katz would die at the exact moment in his life that things started to look up for him.

Although the total number of military Kardons is reasonably certain, the number of civilian models is not well documented. Jerome Katz estimates that anywhere between 300 and 3000 cameras could have been built, but his best guess was closer to 2000. With such a small number out there, it’s likely most people reading this article will have never handled a Kardon camera, and many might not have even heard of it.

Despite my regular use of failure on this article, I hesitate to call the Kardon a failure. Sure, it failed to sell in large numbers, it failed to keep American intelligence officials from being detected, and it failed to make any appreciable dent in the United States’ role as a leader in the photographic industry, but as a photographic tool, it was a success. Many of the changes made to the military Kardon made it a better camera to use. The larger film advance knob and relocated focus wheel are actually helpful. The use of interchangeable parts that didn’t require hand fitting was something the Germans couldn’t (or didn’t want to) do. And of course, there’s the Kodak Ektar lens which is optically as good as anything the Japanese or Germans could make at the time.

Today, the Kardon camera is highly sought after by collectors and prices are all over the place. Although Leica copies from the Soviet Union and Japan are extremely common, ones from other countries like the United States are extremely rare. Add in some features that possibly make it a better camera, and a really cool history and you have the perfect recipe for a camera with a sky high price tag.

My Thoughts

I had wanted to test a Kardon camera from the moment I first learned of it’s existence quite a number years ago, but the camera’s rarity and value meant that if I ever had a chance, it would most likely have to come in the form of a loan. Earlier this year, I had thought that perhaps I should do another American themed review month this July and if I was going to that, I would need a special camera to be the highlight of the month.

The last time I did this was in July 2019 and at the time I was lucky enough to review both the Kodak Ektra and Bell & Howell Foton, but for this year, what would that special camera be? One day while talking to fellow collector and blogger, Dan Cuny, he mentioned he had a Kardon to which I asked him if he’d be willing to loan it out for a review to which he happily agreed. Dan had previously written his thoughts regarding this same exact camera on his own site, but having never shot the camera, nor having access to Jerome Katz’s book, he was only able to share the same short history that was easy to find online.

When it arrived, you can clearly see the duller, satin finish which was a quality of the military Kardons. Civilian models use a shinier chrome like the real thing, but the military versions needed to be corrosion and fungus resistant, so I imagine the duller finish is a result of that. I was impressed with the overall build quality of the camera. The Kardon is smoother in operation and feels better made than any Soviet Leica copy I’ve handled, and on par with Japanese Nicca or Canon copies. Without a lens attached, the camera weighs 454 grams, which is about 50 grams heavier than a Leica IIIc, but holding one in each hand, I can’t say that I can tell the difference.

The Kardon started out as a copy of the Leica IIIa, so the majority of it’s controls are in the same locations and work much in the same way as that camera, so if you’ve ever used a screw mount Leica before, then you’ll likely feel right at home with the Kardon, with only a couple differences.

The top plate starts with a small popup rewind knob for returning the film back into the cassette at the end of a roll. Around it’s perimeter is the diopter adjustment for the rangefinder window. On the raised portion is both the Kardon logo and accessory shoe. Notice how the usual signs of a Soviet knock-off are not here. Every single engraved marking is paint filled like a real Leica. The top edge of the front viewfinder window does not extend all the way to the top, nor does the edge between the top plate and accessory shoe have that gradual curve of FEDs or Zorkis. The Kardon is very faithful to the original camera in this area.

On the right are the shutter speed dial with fast speeds from 20 to 1000 plus Bulb, the raised shutter release button, advance/rewind mode selector, and finally, the combined exposure counter and film advance knob.

This being a military Kardon, it has a much larger film advance knob than civilian Kardons and pretty much every other Leica or Leica copy. In my review for the Nicca made Tower 45 which replaces this knob with a film advance lever, I noted that while it might seem that a film advance lever is a good upgrade, it does not add to the experience of shooting the camera. While film advance levers were great additions to other cameras, it didn’t make me wish Leitz had included one on a real Leica.

With the Kardon however, the larger film advance knob is quite pleasant to use. The increased diameter and height of the knob makes it really easy to grip and fast to use. Three short movements of my fingers is all that’s needed to fully advance the film and cock the shutter. The larger size also allows for a larger exposure counter which is easier to read. The counter still requires that you manually reset it after loading in a new roll, but I appreciated the larger size and can see how this would help someone wearing heavy gloves.

The back of the camera is where two changes would be, the most glaring of which is the missing US Signal Corps plaque that should be there, which on this example had been removed leaving four holes which I needed to cover up when shooting. Civilian Kardons would not have this plaque.

The only other change seen from the back on military Kardons are the short extensions on both the rangefinder and viewfinder windows. I imagine this was done to make the camera easier to use with goggles or a face mask on, but as a wearer of prescription glasses, I can’t say that it made any difference for me.

The bottom plate is nearly identical to the original Leica III with a 1/4″ tripod socket on one side and a film compartment lock that also doubles as the cassette release for Leica style reloadable cassettes. With a metal cassette loaded into the camera, the film lock rotates two notches on the cassette opening the light trap, allowing film to easily transport inside the camera. When you move the lock to the open position, the notches close the light trap, preventing light from entering through the light trap with it out of the camera.

Film loads exactly the same as any other bottom loading Leica or Leica copy. With a new roll of film, you must trim the leader to about 10cm, or the full distance from one spool to the other before inserting it into the camera. The take-up spools are removable, and although the one that came in this Kardon was solid metal, the spring loaded ones used in Canon and later Leica rangefinders also work too.

The Kardon uses the same 39mm screw mount as the Leica and uses the same style of rangefinder coupling, meaning that Karon and Leica lenses are interchangeable with each other. In the history section above, I show a picture of the Kardon with a Leitz Elmar and the Kardon’s Kodak lens mounted to a Tower 45. I doubt many people would have done this back then, but had the Kardon been more of a success, there likely would have been a larger number of people swapping with German and Japanese M39 lenses.

Another of the Kardon’s unique features is the fine focus wheel on the Kodak Ektar lens. Rather than a metal tab like on pretty much every other screw mount rangefinder lens, the Kardon uses a geared wheel which was said to be easier to operate while wearing gloves. The position of this gear varies on lenses made for the military vs civilian models. On the military ones, the wheel is located near the 8 o’clock position around the lens, but on civilian versions, was near the 10 o’clock position.

Although I didn’t have access to a civilian model, this seems a little more awkward to use as it’s close proximity to the slow speed dial might have made it harder to reach. Regardless of which version you have, you can still focus the lens by gripping the outer barrel and rotating it, but of course you have to make sure your hand isn’t blocking the lens when making an exposure.

The front of the Kodak Ektar lens is not threaded for filters, but is the correct size to accept Series V press-on filters if you do desire. Behind the front lens element is a knurled wheel for controlling the diaphragm. Clickless f/stops from 2 to 16 are available.

The viewfinder is modeled exactly the same as the one on the Leica IIIa with a straight through viewfinder on the right, and magnified rangefinder window on the left. The military Kardon has two small extension tubes around each viewfinder window, seemingly to make it easier to use while wearing glasses, but to be honest, I noticed no improvement. The image to the left shows a composite image of both windows side by side, when in reality you cannot actually see through both at the same time like this.

Handling the Kardon is close enough to a real Leica that anyone whose used one before should know what to expect, but with a few changes like the larger diameter advance knob, extensions on the viewfinder and shutter release, and the geared focus wheel offer just enough difference to make it interesting. Although it was common for many Leica copies to deviate from the original formula, not every change made by other companies improved the camera, but the Kardon may be one exception to that rule.

My Results

When Dan agreed to loan me his Kardon, he warned me he had never shot it. Although it was in good cosmetic condition, he couldn’t verify the functionality of the shutter, plus, the US Signal Corps plate that’s supposed to be on the back of the camera had been removed, leaving four holes through the door into the film compartment which would need to be covered before film could be shot in the camera.

The four holes were easy enough to cover with black electric tape, but for the shutter, I took the lens off, and dry fired it a variety of times and found that the slow speeds definitely had issues and the fastest speeds did not separate correctly, but the middle speeds looked like they were working.

Not willing to risk losing a roll of more valuable film on a camera with so many question marks, for the first roll I loaded in some bulk Kodak Plus-X 125. I generally shoot this film like a 100 speed film, so my plan was to limit the camera’s shutter only to the 40, 60, and 100 speeds and control aperture with the diaphragm.

I kind of had a feeling of what to expect when shooting the Kardon as I know Kodak lenses are good and I’ve shot many Leica-like cameras. The biggest mystery was whether it worked or not. The owner of this camera had never shot it before me, so the question was never if the images would be good, it was whether I’d get any at all.

Upon taking the film out of the development tank, I could immediately see sharp and properly exposed images. Upon scanning them, the exposure looked correct, there weren’t any obvious light leaks, but there were some very strange horizontal streaks across the entire roll. This film came from a bulk 100′ roll of Kodak Plus-X that I had shot before which didn’t show those streaks, yet inspecting them on my monitor, they also don’t look like the usual scratches that you’d see from a camera with a rough film plane or pressure plate. To be perfectly honest, I still don’t know where they came from, but looking past them, I feel there’s enough in the images to declare the Kardon and it’s Kodak Ektar lens a winner.

Images are sharp and evenly exposed corner to corner. I saw no vignetting or obvious optical anomalies anywhere in the frame. Taking a camera designed for military use to a local war memorial, I feel as though I could be looking at images shot decades before I was born.

Since my time with the Kardon and it’s Kodak lens was limited, I wanted to see what it could do when shot digitally, and armed with an M39 adapter for my Fuji X-T20 digital mirrorless, I shot a couple quick test photos using the lens.

Like the film images, the digitals are razor sharp corner to corner and do not show any obvious optical anomalies characteristic of lesser lenses. I did notice a subtle lack of contrast, especially with backlight, as seen in the photo of my cat against a bright window, but this is to be expected of early lens coatings. Overall, I can say that the Kodak Ektar lens is a winner, regardless of the medium you shoot it on.

I loved using the Kardon, maybe even more so than the camera it was based off. In every way the Kardon changed something from the Leica, it either improved something or kept it the same, but never made it worse. The larger diameter film advance knob worked really well and was something I wish other companies had tried. The viewfinder was small and squinty, but didn’t impede my ability to compose and focus any of the shots on that first test roll. I also found the geared focusing wheel to be a bit too stiff for my tastes, but I am certain this is a condition of age. With proper servicing and lubrication, I imagine it would be as pleasant to use as the similar wheel on a Contax or Nikon rangefinder.

There are a lot of Leicas and Leica copies out there and I’ve used quite a number of them, but the military Kardon might be my favorite. The combination of a well built camera, a great underdog story, some American patriotism, and just enough of a change from the original makes the Kardon a winning formula. With a smaller advance knob, I might not have liked the civilian Kardon as much, so I am very happy to have had a chance to play with this example.

If Jerome Katz’s estimates of no more than 2000 of these made are correct, means that they won’t show up for sale often, and when they do, prices are likely to be high. If you have a larger budget and want something that is both different and has a good story, I definitely recommend picking one up! I know I would!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://www.dancuny.com/camera-collecting-blog/2020/8/24/kardon-camera

https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/buy/kardon/kardon.htm

http://www.novacon.com.br/odditycameras/kardon.htm

https://www.shutterbug.com/content/kardon-camera-american-tale

Kodak AG – Dr Nagel Werk, Stuttgart-Wangen, Germany, put the Eastman Kodak Company “lumenized” Ektar f/2 47mm lens on a Retina II they made for the American PX system. The lens on the camera I have has the date code “EO” (1946). This model Retina is easier to find and much cheaper than a Kardon. If anyone wants to see how the lens performs, he or she could hunt for one of these.

excellent story! there’s a lot in here that I head never heard before. thanks Mike!

What a fascinating history and background of this camera.

What I find interesting is the parallel with the British made Reid & Sigrist version of the Leica, in that both this and the Kardon came about from our respective Governments’ desire for a high quality 35mm camera for military use owing to the shortage of Leicas, post war, and both became available for well-heeled civilians to purchase as well. And both improved on the Leica bodies they were based upon, with the Reid staying with the same cosmetic body style but improved on the mechanical innards, and the Kardon making some visual changes, such as the larger wind knob for military use coupled with the unique lens focusing gear and which sets it apart from the civilian model lens in which the gear wheel will always be at the 10/11 o’clock position, versus the 8 o’clock position with the real military bodies. Nice and easy givaway for collectors who want a genuine military body! And helps me, should I ever get the urge to supplement my Reid with one.

Given its rarity, I was just a little surprised that the Kardon shutter was defective as I would have assumed the owner would have got it seen to, unless it is there purely as a display piece. You mention in your article how the company overcame the need for all the hands-on adjustments that Leica used and and I was wondering if the approach with the Kardon has left the shutter less amenable to repair i.e. is it non-standard compared to that in many Leicas that makes these easier to service?

Thanks for the information and motivation. I just bought one to go with my other 7 Barnacks.

One just sold on the Shopgoodwill.com for $2000 (07/11/2023). Seemingly in very good condition with leather case in very good condition.

I think the Reid with the Taylor Hobson is a better combination.

I like the article a lot. It gives ample history of the camera. I really like the 2023 comment that shows that one sold for $2000 this past year. That comment got me excited because I have a military version of the Kardon camera. Now, the question is ; What should I do with it? Who should I contact about this? Anyone with any answers?

Try Ebay. Sell it at auction with a strong starting price. Make it available in Japan and Europe, as that’s where many good buyers are located. (I’ve sold analog photo gear on Ebay for two decades under the name “roger_baker”).