If your experience with photography is limited to hand held 35mm or roll film cameras made within the last 100 years, you likely have never heard of the Packard shutter. The history of the Packard shutter and how it came to be is shrouded in mystery. There is very little information about it online and what little there is conflicts with other information out there.

The Packard Shutter

What we do know is that the shutter’s history starts in the late 1800s. A photographer turned inventor named Cullen C. Packard registered a number of patents in the United States between the years of 1885 and 1895 for a camera shutter that closely resembles the earliest Packard shutters.

Cullen Packard was born in Cummington, Massachusetts in October 1840 to parents Royal L. and Mercy H. Packard. In June 1862, he registered as a volunteer soldier in the 10th Regiment of the Massachusetts Infantry. Packard fought in the Civil War, seeing action in a large number of battles, including Gettysburg and Antietam before mustering out on July 6, 1864 with the rest of the Massachusetts Infantry.

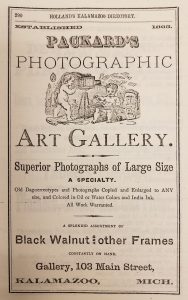

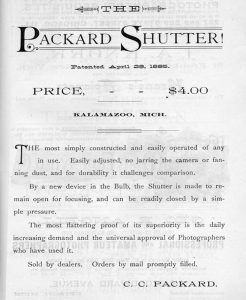

After the war, Packard relocated to Kalamazoo, Michigan, and sometime in 1865 started the Packard Gallery at 103 Main Street. The first known evidence of a photographic shutter designed by Cullen C. Packard is US Patent number 316,564 from April 28, 1885. It stands to reason that Packard was not happy with whatever equipment he had been using up until this point and designed a new shutter for his own use.

The ad to the right is from an 1887 catalog for James W. Queen & Co out of Philadelphia, PA. This is the earliest known advertisement for Packard shutters, and is notable as it only mentions ‘C.C. Packard’ suggesting it was sold direct from Kalamazoo.

Over the course of the next decade the story of the Packard shutter intertwines with that of the E. & H. T. Anthony & Company (later known as ANSCO) of New York, NY. At some point between Packard’s first shutter in 1885 and 1891, he would partner up with the Anthony & Company and register a new pneumatic shutter with the US Patent office. Patent 451,880 was registered on May 5, 1891 and appeared to be an improved version of Packard’s original design.

What agreement he had with the Anthony & Company is unknown, but both names appear on the 1891 Patent documentation. It is likely that Anthony & Company sold Packard designed shutters under their own name, but I cannot confirm this. Around the same time as Packard’s 1891 shutter, another Kalamazoo inventor named Garrett W. Low would register patent 471,675 with the US Patent Office for another photographic shutter. Based on the drawings on the patent, Packard’s 1891 shutter and Low’s 1892 shutter look nothing alike. Whether Low’s shutter was a rudimentary design that he had created to compete with Packard’s is anyone’s guess. I don’t even have any evidence that Packard sold his shutter around the time that Low registered his, so there might not have been any competition at all.

What we do know is that by 1895, Packard founded his own shutter manufacturing company without the help of Anthony & Company. According to paperwork found at the Kalamazoo Public Library, the address of Packard’s company was 302 North Burdick. On Nov 12, 1895, Cullen Packard would register one final design with the US Patent office as patent 451,880, once again for a pneumatic shutter. This appeared to be Packard’s final design, and the one that he would put into production.

All was not well, however. Unlike Packard’s 1891 patent, the E. & H. T. Anthony & Company name appears nowhere on the 1895 patent documentation. It seems that there was some type of disagreement between Packard and the Anthony & Company. This is pure speculation, but perhaps the Anthony & Company claimed rights to Packard’s design and was not happy with him wanting to keep the design for himself. Maybe they wanted to be included on the 1895 patent and were left out. No one really knows what happened, but the story seemed to make a dire turn as on June 1st, 1898, Cullen C. Packard would commit suicide. In his suicide letter, he blamed the Anthony & Company suggesting that he was taken advantage of for the past 10 years.

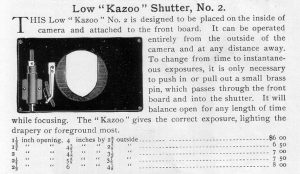

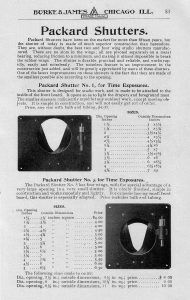

It would seem that the Anthony & Company had used a variation of Packard’s 1891 shutter design for their own series of shutters that were accredited to Garrett Low. Various Anthony catalogs from the 1890s feature a variety of Low shutter that look a lot like the Packard shutter. The image to the left of a Low Shutter No. 2 looks suspiciously like a Packard shutter. It seems unlikely that both Low and Packard would coincidentally create shutters featuring similar curved shutter blades, a pneumatic release, and a very thin, behind the lens design. Whether it was a complete knock off, or just inspired by Packard’s design is anyone’s guess, but I think this most likely was the cause of the rift.

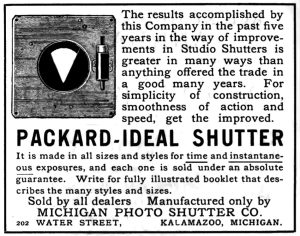

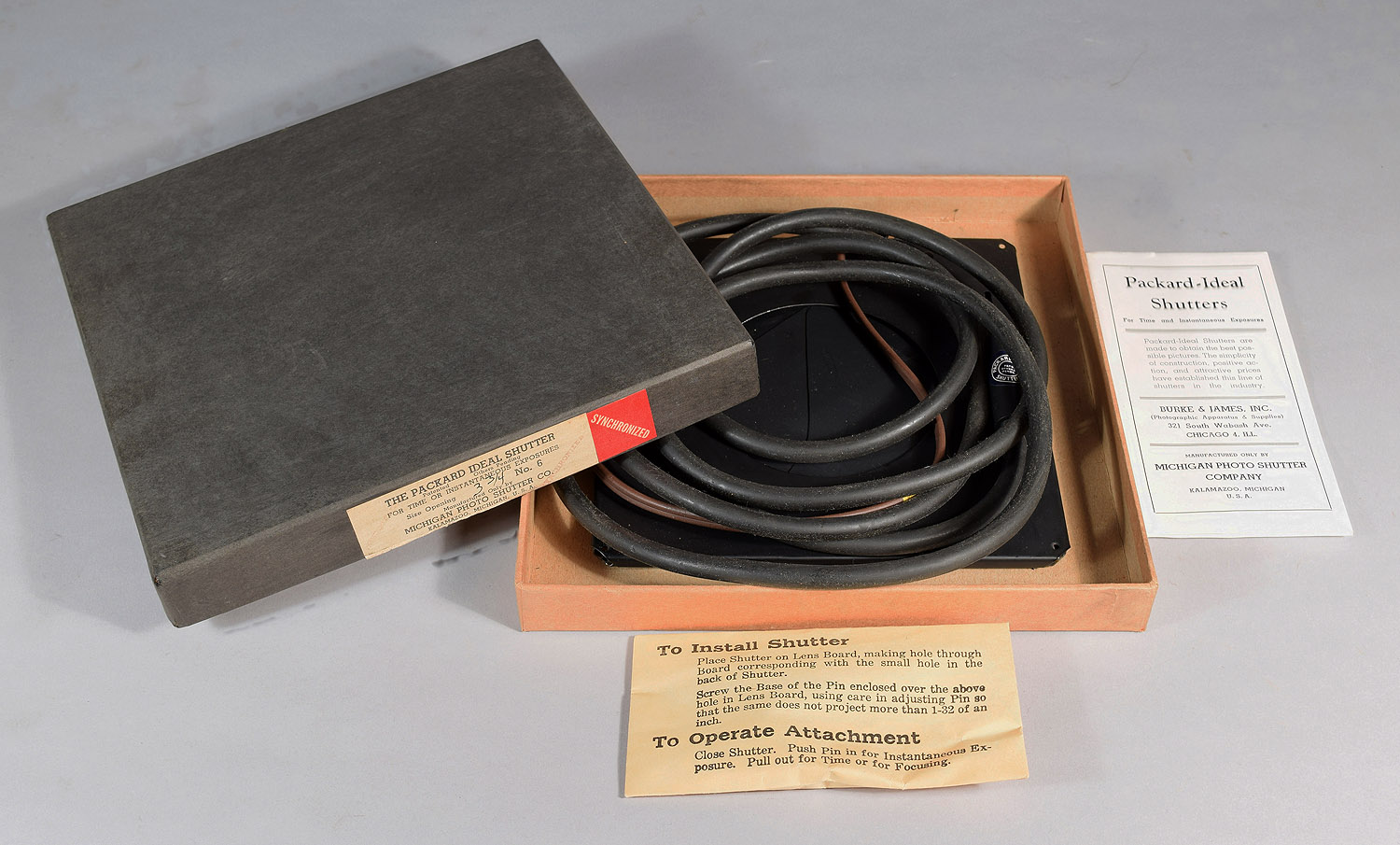

After Packard’s death, the remains of Packard’s shutter company were purchased by a man named Walter G. Henshaw, but not much is known about what happened to it over the course of the next few years. Henshaw would not show up in any documentation until about 1903 when he founded the Michigan Photo Shutter Company (MPSC) and through this new company would sell what was then called the Packard-Ideal Shutter.

MPSC would change hands first in 1911 when Walter Henshaw died, to his daughter Luna Henshaw. A newspaper article from October 1925 states that MPSC produced 3 different types of Packard shutters, most likely the Nos. 5, 6, and 8 for various size cameras.

Over the course of the next several decades, the Packard shutter’s reputation continued to grow. It was sold through a variety of photographic retailers all over the world such as Burke & James in Chicago, Seneca Camera Mfg. & Co in Rochester, NY, and Dallmeyer Lenses & Cameras in London. The ad to the right is from the 1911 catalog for Burke & James who claim them to be “without a doubt the best two and four wing studio shutters made.” The Packard shutter was known for it’s reliability, simplicity, and quiet design.

The Packard shutter would continue to be made by MPSC, and would remain in the Henshaw (later Hardy) family until 1968 when it would be sold to Malcolm B. Brooks of Kalamazoo, Michigan. It would not stay there long, as in 1973 the company would change hands once again to Reno Farinelli Sr of New Jersey who moved the company from Kalamazoo, MI to Hammonton, NJ. The Packard shutter product became part of Professional Photographic Products, Inc. who also made matte boxes and passport cameras, among other things.

Farinelli Sr would continue to operate the company until he retired in 2005, handing the company over to his son, Reno Farinelli Jr who moved the company once again to Fiddletown, CA. The other products from Professional Photographic Products had since been sold off to the Tiffen Company, or just discontinued altogether. Upon relocating the California, the company was renamed the Packard Shutter Company and would exclusively produce shutters.

This was the story of the Packard shutter and the various companies that produced them, until now…

The Packard-Ideal Shutter Company

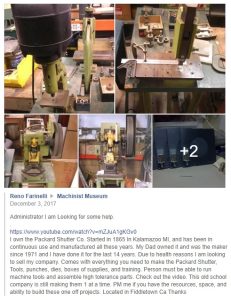

In December 2017, a post was made on various photography related Facebook groups by then current owner of the Packard Shutter Company, Reno Farinelli Jr that he was putting his company up for sale and was looking for someone to take over the business.

In December 2017, a post was made on various photography related Facebook groups by then current owner of the Packard Shutter Company, Reno Farinelli Jr that he was putting his company up for sale and was looking for someone to take over the business.

Little did I know that this post attracted the attention of fellow photographer and vintage camera enthusiast, Jon Gilchrist. Jon is a member of the Facebook Vintage Camera Collectors group whom I am also a member of and by the end of January let me in on his secret that he would be purchasing and running the company himself.

A quick search of the Internet to know more about Packard shutters piqued my interest and I asked Jon if he’d be interested in an article that would serve both as a historical reference for the company, but also to help get the word out about the company’s new ownership.

I met up with Jon on February 25th and recorded a Q&A session going over some things that he wanted the world to know about his new company, which he was renaming the Packard-Ideal Shutter Company. What follows is a summarized version of our conversation:

Mike E – Hi Jon, lets start off this interview with the question that my wife, and likely most people’s significant others would ask when told someone had bought their very own shutter company, which is, Why? What drew you to wanting to do this?

Jon G – *laughs* Good question! My interest in the idea of owning a company like this relates to my background in design, engineering and photography. I’ve been taking photos since the 6th grade and over the course of my life have worked for a variety of engineering companies. I have 4 patents in my name, but unfortunately spent a lot of time working for companies who didn’t really care that much for their people. I’ve spent the last 10 or so years doing odds and ends waiting for a time to use my considerable experience and knowledge with a company I could run myself and put my passion to good use.

When I saw Reno Farinelli’s post on Facebook in December, it intrigued me because not only was I already familiar with Packard shutters, having owned a few in some cameras I had in the past, but it seemed like a perfect fit for me. It was a mechanically built, low production product that has gone unchanged largely for the past 60 years and could be built and sold entirely as a one man operation.

Mike E – Wow, so one person can run the entire company by himself?

Jon G – That’s the plan. I have the knowledge and the necessary skills to build something like this. Everything is hand made, built one at a time. Everything is done in small batches with no assembly lines. I am fully responsible for the quality control of the product.

Mike E – How long does it take to make a shutter and get it to your customer?

Jon G – Well, I just started, so I am intentionally taking things slow so that I can learn the business and make sure I do everything the right way. The assembly times vary wildly based on the specifications of each shutter as there are a variety of sizes and options available. My current turnaround time is about 6 weeks from the time an order comes in to the time I am ready to ship it out.

I am currently working on an order that will be going to England so obviously there will be additional delays in shipping too. My goal is to reduce that turnaround to time to as little as one week from ordering to shipment for shutters with standard configurations.

Mike E – What kinds of options or different configurations are there?

Jon G – Well currently, there are only two basic models of the Packard-Ideal shutter that I am building. The No. 5 and No. 6 shutter are the only two models that have been built for the last several decades. The difference between the two is that the No. 5 is Time, or Bulb exposure only, and the No. 6 can do both Bulb and instantaneous (around 1/25th of a second) exposures.

In terms of options, you can configure the shutters to have synchronization sensors that tell whether the shutter is open or closed, you can have various ways of actuating the shutter from a simple rubber hand operated bulb, pneumatic and electronic actuators, or even levers.

Mike E – What are the shutter blades made out of?

Jon G – That’s another option too. Most Packard shutter blades are made of a plastic composite material that works in most applications, but for heavy duty applications, they can be made of steel or aluminum too.

Mike E – What types of heavy duty applications are there?

Jon G – Packard shutters have a lot of uses beyond photography. They are used in science and technical applications such as optical instruments and telescopes. An interesting application for shutters in telescopes is that they’re used opposite of how a photographer would use them in that the shutter is left open almost all of the time to let continuous light into the telescope and only closed on occasion to calibrate or to move the telescopes.

Mike E – I have to imagine a telescope shutter is probably a lot larger than a camera shutter. How many different sizes are Packard shutters available in?

Jon G – Currently, the smallest shutter has an internal diameter of 1.5″ and they’re available in quarter inch increments up to 3″. Then from 3″ to 6″ in half inch increments, and then from there in whole inch increments. The largest that I can currently make is an 8″ shutter, but there were once plans for shutters as large as 11″ inches which were made as custom orders in the past. That’s one of the best things of the Packard shutter design, is that it can scale very well with little change in how it’s made.

Mike E – Besides scientists and telescope operators, who is going to be your typical customer?

Jon G – Someone doing wet plate or view camera photography. Large cameras with barrel lenses without integrated shutters would need a shutter like the Packard. These cameras are designed for long exposures. If you need a shutter capable of speeds like 1/500 or 1/1000 of a second, then it’s not for you, but if you need a 3 minute exposure then you’re in luck!

Mike E – I have to imagine that there aren’t a lot of other competitors when it comes to shutters like the Packard. Who is your main competition?

Jon G – No one! Back in the late 1800s when Cullen Packard created this shutter, there were tons of other companies making similar products. When you look through old Central Camera or Burke & James catalogs, there were whole sections of the catalog devoted to shutters like these, but as the years have gone on, all of those other companies have either disappeared or stopped making shutters. The Packard shutter was recognized over 100 years ago as being incredibly well built and reliable and as a result has survived all these years to the point where it’s the only thing like it left in the world.

Mike E – When you purchased the company, what all did you buy? Are there trademarks or patents that you now own which allow you to still use the Packard name?

Jon G – All of the original patents for the original design have expired many years ago, but the trademarks still apply. I still need to get some paperwork in order to fully register the name, but I am the sole owner of the Packard shutter and the trade secrets that are needed to build it.

Mike E – Can you describe the process of buying the company? Did you fly out to California and drive back the equipment or hire a trucking company to pick it up?

Jon G – I went out to Sacramento to meet up with Reno and his family and they were very welcoming to me. Reno has had the Packard Shutter Company in his life ever since he was a kid and it was very important to him that it get passed onto the right person to continue the company’s legacy. He ran the company largely unchanged from when his father owned it out of a love for the product and it’s history.

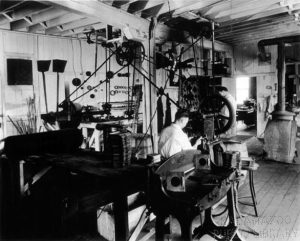

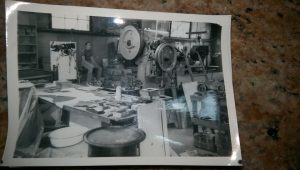

I stayed out there for a little over a week and went over the assembly of the shutters, how the company worked, and he answered many of my questions. When it was time to come home, I rented a 26′ box truck and a friend of mine met me out there to help me load everything up and drive it back home to South Bend, Indiana. I basically brought back a full sheet metal shop, including punch presses, lathes, spare parts, random tools, and many other parts. Amazingly, that wasn’t even all of it. I left behind some presses that I didn’t think I’d need as I’d like to one day look into more modern manufacturing techniques such as laser cutting machines. Reno agreed to hold onto any spare equipment for a period of time in case I ever decided I needed it.

Mike E – Was there anything that you brought back that’s original to the company that Cullen Packard might have used?

Jon G – Nothing quite that old. There was a metal shear that dated back to about 1924 and some other machinery parts from back then but nothing quite as old as from the 1800s. Machines wear out over the time and need to be replaced or updated, so the ages of the equipment varies.

Interestingly, Reno had a picture of himself as a child sitting on a stool when his father was looking to buy the company from it’s original owners in Kalmazoo. He still has that stool and said it was very old even back then, so that came with too!

Mike E – What about raw materials? Do you plan on sourcing the raw materials for the shutters from local businesses?

Jon G – My plan is to source as much as I can locally. South Bend has a rich history in manufacturing and there are still places I can get a lot of my materials from. Included in the sale of the company was a huge supply of screws and copper bushings that will likely last me for the rest of my life, so many of the parts won’t ever have to be sourced.

Mike E – Is an all-Midwest, American built shutter important to you?

Jon G – Absolutely! One of the biggest appeals to this product is that I can hand build everything myself. I have complete control over everything that goes into every shutter, and I am incredibly proud to be able to not only make an all American product, but one that both has a history in the American Midwest, but is being made there once again.

Mike E – You’re not planning on moving back to Kalamazoo though, are you?

Jon G – *laughs* No. I am quite happy where I am at. I’ve gone back up to Kalamazoo to do research at their library and I think very highly of the area, but South Bend is my home.

Mike E – Are there any plans for the future to develop new types of shutters or products?

Jon G – I am definitely looking for ideas to expand and round out my offerings, but since I’ve only just begun, those are ideas for a later time. I have a few ideas that are just in my head though that I’d rather not talk about, but am listening to my current customers and will take any suggestion that someone might have on ways to improve the product.

Mike E – What about the website? I noticed that it’s rather simple and doesn’t offer any kind of electronic ordering. Is that in the cards?

Jon G – Yes, I want to redo the entire packardshutter.com website and make it more modern and add e-commerce as an option. Like I said before, the Packard shutter is very customizable, and each order is hand built when the order comes in, but I do foresee some “standard” configurations of shutters in common sizes with options that are the most common that people can go online, pick what they want, put in their credit card info, and place an order. As soon as I get an order, I’d start building it and ship it out as soon as possible.

Mike E – That’s all I can think of for now. Was there anything else you’d like people to know about yourself or your new company?

Jon G – Just that we’re still here. Cullen Packard’s first design for a shutter is from 1885, and there is evidence of him selling his products before the first Kodak camera was ever made. Packard shutters have been around for a very long time, and have an important place in the history of photography and I am extremely proud to keep it alive!

If you are interested in more information about Packard shutters, visit their website at http://www.packardshutter.com/ for more information.

Hi – do you know if Jon is still running the Packard Shutter C.? I placed an order weeks ago and have not heard a peep. Any way you can help me get in touch with him?