When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the Earth…

This is a followup to an earlier post I spontaneously wrote back in August called “The Cameras of the Dead”. In that article, I applied a tongue in cheek analogy to George Romero’s 1968 classic “The Night of the Living Dead” to a small, but growing list of dead cameras that I had acquired and intended to write a full review for, but for one reason or another, were not operable enough to complete a full review.

In the early days of writing reviews for this site, I tried to hold myself to a standard to only review cameras that I could show results for, but no matter how hard I would try, some cameras were either too far gone or simply beyond my capability to repair. Sometimes these cameras would come to me broken and I would quickly realize that no amount of effort would get it to a usable state, others I had made a valiant attempt to get it working, only to discover later that there were more issues that I was unable to overcome.

I found it a shame to do nothing with them because some of these cameras were still quite fascinating and worthy of some type of review. So, the original “Cameras of the Dead” article featured 3 models that I had acquired over the years which were not usable. In the article I gave a very brief summary of the camera, listing it’s specs like I always do, and I would talk a bit about my thoughts of the camera, how it worked, and what went wrong. Since I wouldn’t have any examples of photographs from any of these cameras, I wouldn’t have any samples to share, and I would try to keep the editorial comments to a minimum.

As it turned out, that article proved to be quite popular and I saw the “hit counter” in my WordPress dashboard indicate it as one of the most read articles in the weeks that followed. Since I have more unusable cameras, I figured a part two would be in order. Keeping with the George Romero theme, the title of this article takes a cue from Romero’s followup to his original film, 1978’s masterpiece, “Dawn of the Dead”. Although a very decent remake was done with the same name in 2004, I still hold the original in high regard as the best zombie movie ever made. The remake certainly benefited from much more advanced makeup and more horrifying looking zombies, but the original captures a mood and feel of what living in a zombie apocalypse might be like which elevates it to a level that no other zombie movie has ever been able to match.

As it turned out, that article proved to be quite popular and I saw the “hit counter” in my WordPress dashboard indicate it as one of the most read articles in the weeks that followed. Since I have more unusable cameras, I figured a part two would be in order. Keeping with the George Romero theme, the title of this article takes a cue from Romero’s followup to his original film, 1978’s masterpiece, “Dawn of the Dead”. Although a very decent remake was done with the same name in 2004, I still hold the original in high regard as the best zombie movie ever made. The remake certainly benefited from much more advanced makeup and more horrifying looking zombies, but the original captures a mood and feel of what living in a zombie apocalypse might be like which elevates it to a level that no other zombie movie has ever been able to match.

I don’t mean to turn this article into a movie review, but as Dawn of the Dead was superior to it’s predecessor, I will try to top that first Cameras of the Dead article with three more “dead” cameras.

Kodak Retina Reflex III (1960)

This is a Kodak Retina Reflex III 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera from 1960. The Retina Reflex series was a continuation of the earlier rangefinder Retina, and shared many of the same parts, including the body, lens mount, and leaf shutter. Released to capitalize on the rising popularity of the SLR camera, Kodak AG in Germany decided that rather than design an all new SLR camera from the ground up, that the Retina rangefinder could be turned into an SLR camera by adding a mirror box, reflex mirror, and pentaprism finder. They mostly succeeded, but where most SLRs of the day had a focal plane shutter, the Retina Reflex series used the leaf shutter from the earlier Retina. This proved to be a technical nightmare, and it plagued the Retina Reflex with reliability problems, and is one of the reasons that very few surviving copies work properly today. Still, the Retina Reflex maintained the high quality standard of earlier Retinas, and included well built lenses that had excellent optics.

Film Type: 135 format 35mm film

Lens Mount: Retina Bayonet Mount (Front Group Only)

Lens: 50mm Schneider-Kreuznach Retina-Xenon f/1.9 coated 6-elements

Focus: 3ft to Infinity

Shutter: Synchro-Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500

Exposure Meter: Gossen selenium cell with match needle visible in viewfinder

Battery: None

Flash Mount: PC socket M & X flash synchronization

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_retina_iii.pdf

My Thoughts

The 1950s was a very exciting time for film photography as most people had settled into “normal” lives after the conclusion of the war. Japanese and German companies had ramped up their abilities to produce new products, and innovative new cameras were released sometimes months apart. Between the mid to late 1950s, many companies threw their hat into the SLR market by releasing their first models.

Asahi (Pentax), Orion (Miranda), Minolta, Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), and Canon all released new lineups of SLR cameras during this period and their accurate (and sometimes interchangeable) viewfinders with interchangeable lens mounts were appealing to professional photographers. Although many of these early models were quite expensive, it only took a couple of years for the prices to come down with more modest models being released aimed at the advanced amateur.

Around this time, Kodak knew that in order to stay relevant in the camera market, they too, had to have their own SLR camera. For reasons that I’ve never been able to discover, rather than design a new camera from the ground up, they chose to modify the existing Retina III rangefinder, and add a mirror box with reflex mirror and pentraprism viewfinder on top. The new Retina SLR would be called the Retina Reflex and went on sale in the spring of 1957 with a retail price of $215, which when adjusted for inflation is over $1800 today.

Kodak would use the same bayonet lens mount as the Kodak Retina IIc and IIIc models so that lenses could be interchanged between rangefinder and SLR models. This later changed to a SLR only bayonet mount on the Reflex III and later models. Other features carried over from the rangefinder Retinas were a modified version of the Compur leaf shutter, bottom wind film advance, and Gossen selenium cell light meters.

While it might seem that using a leaf shutter on an SLR might have been a straightforward swap, it actually was quite complicated. For one, in a focal plane shutter, the reflex mirror which reflects light up into the viewfinder is in front of the shutter. The shutter can remain shut, blocking light from the film plane up until the moment of exposure. On a leaf shutter camera, the shutter is in front of the reflex mirror, which means that in order for light to be reflected up into the viewfinder, both the shutter and aperture iris must remain wide open while composing. Since the shutter is open at all times while composing an image, a separate flap called the “capping plate” must fold down behind the mirror, blocking light from entering the film plane and prematurely exposing the film. The image to the right shows the capping plate in it’s closed position in the film compartment blocking light from hitting the film during composition.

During storage, or when the shutter is not cocked, the shutter remains closed, and the mirror and capping plate remain in the upright position, blocking all light from entering the viewfinder. In order to see through the viewfinder, you must first advance the film using the wind lever on the bottom of the camera.

Then, when the photographer is ready to capture an image, a convoluted series of events must unfold to first close the shutter, then the capping plate and the reflex mirror flip up out of the way, the aperture iris stops down to it’s selected setting, the shutter reopens to expose the film for whatever length shutter speed has been selected, then close again to stop the exposure, all while happening upon the moment the shutter release button is pressed. This whole sequence takes approximately 1/50th of a second to complete which isn’t a huge amount of time, but the delay could cause problems shooting moving objects as the image would be captured 1/50th of a second after you intended it to.

The following table summarizes the events that must unfold each time a photograph is taken with a leaf shutter SLR.

| Stage | Shutter | Iris | Mirror | Capping Plate |

|

| 1 | Composition | Wide Open | Wide Open | Down | Down |

| 2 | Preparing to Fire | Closed | Stopped Down | Up | Up |

| 3 | Exposure | Open | Stopped Down | Up | Up |

| 4 | Uncocked Shutter | Closed | Wide Open | Up | Up |

| 5 | Wind Lever | Wide Open | Wide Open | Down | Down |

The Kodak Classic’s website has a pretty good explanation of how this works with some basic drawings which might help you understand it better if my explanation doesn’t make sense.

If this sounds like an overly complicated way to make an SLR, you’re right. While overall it did work, the chances for failure were higher for leaf shutter SLRs compared to focal plane SLRs due to the extra moving parts, and the cost to get them repaired was substantial. While I could not find any evidence of this, I would suspect that many repair shops back then might have declined service on models like these for this very reason.

To be fair, Kodak was not the only company with a leaf shutter SLR, as Zeiss-Ikon, Kowa, and a few others tried it as well, but the end result is a shutter design with more opportunities to fail. This is why after many decades, finding one of these cameras today with a working shutter is very hard to do.

All was not bad however, despite the complex shutter design, the rest of the Retina Reflex SLR maintained a high build quality comparable to their rangefinder cousins. The rest of the camera is a mixture of good and awkward.

Like most Retinas that came before it, the optics were excellent. Most lenses were made by either Schneider Kreuznach or Rodenstock, and were 6+ element designs with excellent sharpness and little to no vignetting or chromatic aberrations in the corners. They had large and bright viewfinders with a split image rangefinder surrounded by a microprism collar on the focusing screen. Starting with the Retina Reflex III, there was a match needle to indicate proper exposure visible inside the viewfinder as well as on the top plate. Finally, keeping on par with all Retinas before it, build quality was excellent.

On the awkward end, despite it’s small appearance, the Retina was heavy and rather top heavy. Weighing in at 971 grams, it’s heavier than 3 different Exaktas in my collection (heaviest of which was 939 grams), A Yashica TL-Electro X at 935 grams, and a Leica M3 weighing 883 grams.

The Retina Reflex also featured some strange controls. Like later Retina rangefinders, the rapid wind lever was on the bottom of the camera. I commented in my review of the Kodak Retina IIc that this bottom wind lever isn’t hard to use, but it offers no improvement to a more traditional top plate design. In addition to the wind lever, the frame counter, frame advance lever, rewind release, film door release lock, and the aperture selector were all on the bottom of the camera, which gives the Retina Reflex III the most cluttered bottom of any camera I’ve seen.

It’s worth mentioning that the aperture selector is a wheel on the bottom of the lens collar, not the bottom plate of the camera, but still, it is on the bottom and definitely requires you to retrain your hand to locate it while shooting compared to pretty much any other camera ever made, ever.

When I made the decision to try my luck with a Retina Reflex, I knew that my chances were slim to find one with a working shutter. Unfortunately, most people buying old cameras on eBay know that as well, so when a model does come up for sale and the seller claims it is in working condition, the prices are quite high. When there’s no statement of functionality, the prices can be low, so I figured that if I was going to take my chance on an unknown one, it had to both be cheap and at least look cosmetically nice.

This particular example was won for around $25 including shipping. I felt pretty good about it because from the pictures, it looked to be in wonderful condition, plus it came with the more desirable Schneider Retina-Xenon f/1.9 lens.

I had a higher than usual amount of anxiety waiting for it to arrive and when it did, I was pleased to see that the camera was in fact in nearly flawless condition, but my excitement quickly turned to dismay when I came to the sad realization that this camera was not operable. You could advance the film transport, but the shutter would not cock, nor would the reflex mirror or capping plate move. I put my most optimistic hat on and thought that perhaps the camera could be returned to working condition through gentle persuasion, or some hidden trick that I could read about online, but after some research, I discovered that my problem was quite common.

Perhaps the world’s authority on all things Retina and their repair, Chris Sherlock’s website retinarescue.com has a troubleshooting section that described my camera’s symptoms perfectly. His conclusion was that this camera had a stripped cocking rack. It seems that having a stripped cocking rack on many different Retina models is quite common, but sadly require a near complete tear down of the camera to replace. If there’s one thing I have learned about Retina repair, is that I neither have the skill or the knowledge to fix them, so I made the wise decision to not even attempt any sort of repair.

Maybe one day, another Retina Reflex will come my way. Many of the ones for sale today are missing the lens, so there’s at least a small chance that I could find a body only camera with a good shutter, and I could swap the nice f/1.9 lens off this one onto the other to have a working camera. While I generally have a rule to only keep cameras that work, I do occasionally make exceptions, and this Retina Reflex is one exception. The camera is actually quite compact compared to other 60s era SLRs, but is a solid metal beast. The camera is beautifully designed and this particular example has bright and shiny chrome, and nearly flawless leatherette, which adds up to a really nice display piece.

I could send this camera off for repair, but these things were difficult to repair back in the 60s, and to find someone today willing to look at them leaves you with pretty much only one person who, once again, is Mr. Sherlock in the land of Mordor. Chris’ repair page quotes a standard Retina Reflex repair price at $240 NZD, plus $35 NZD for a new cocking rack, plus $40 NZD for return international shipping, bringing the total to $315 NZD, which when converted to US dollars, is $227 and that doesn’t even include my cost to ship it to him in the first place.

So, in the end, Retina Reflex III, serial number 140085 has already taken it’s last picture, and is destined to sit on a shelf for the rest of it’s days.

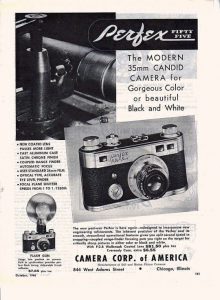

Perfex One-O-Two (1948)

This is a Perfex One-O-Two 35mm rangefinder camera, made by the Candid Camera Corporation of America out of Chicago, IL around 1948. It was one of eight different Perfex models made by the company from 1938 – 1950. Originally featuring a cloth focal plane shutter prior to the war, the Perfex One-O-One and One-O-Two models switched to a more basic, but also more reliable Wollensak leaf shutter mounted inside of a fixed f/4.5 or f/3.5 lens. It was a mild success and represented a very short period of popularity of American made rangefinder cameras, but by 1950, significant competition from Japan and Germany forced the company into bankruptcy.

Film Type: 135 format 35mm film

Lens: 50mm Wollensak Anastigmat f/3.5 coated 3-elements

Focus: 3 ft to Infinity

Shutter: Wollensak Alphax Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1/10 – 1/200

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M-sync port on Shutter, and Hotshoe on camera top plate

Manual (similar model): http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/perfex_fifty-five.pdf

My Thoughts

As an American, I can definitely see the flaws in my country’s history, and the flaws that still plague us today. America is not perfect, but it is a good country and I am glad I was born here. I have always been fascinated with world history, but living in a country who was created as a result of a bunch of guys saying “F*** YOU”, there’s that sense of rebellious underdog patriotism that I think many Americans have.

American patriotism was at an all time high in the years following World War II. Although Germany was the undisputed champion of cameras and all photographic equipment, there was a strong demand for new models at this time, and the idea of an American made camera to compete with the Germans was very appealing. As a result, many American companies appeared out of nowhere right after the war to produce their own models, which they hoped to fill the demand for such products.

Sure, we already had Argus, Ciro, Universal, and Kodak from before the war, but all of a sudden, companies like Chicago based Candid Camera Corporation, Minneapolis based Clarus, and Craftex out of Hollywood, CA all appeared seemingly out of nowhere. At best, you could say that some of the models made by these companies were ambitious, but most were poorly designed cheap models that were rushed to the market with simple shutters and basic lenses.

Technically, the Perfex was released prior to the start of the war, but I think it’s greatest success was right after the war ended due to the huge demand for American made products. There were a total of 8 different Perfex models, the original models featured a proprietary interchangeable lens mount, and a cloth focal plane shutter. Claiming to be the first camera with a focal plane shutter with a flash synchronized hot shoe (Universal also made this claim with the Univex Mercury although it had a unique shutter), it was equipped with a variety of lenses made by Wollensak out of Rochester, NY. The mere presence of so many variants of the Perfex suggests that it sold reasonably well, but could not find any information regarding production numbers over it’s 12 or so year production run.

After World War II, only one pre-war model was still in production, the top of the line Perfex Fifty-Five. Selling in 1946 with a Wollensak f/2.8 lens for $81.50, it wasn’t exactly cheap. When adjusted for inflation, that’s equivalent to $1009 today. While reasonably nice on paper, the Perfex cameras were not built to the same precision as German models. The body was a solid piece of cast metal with a chrome finish. The shutter was not reliable, and although it boasted a top speed of 1/1250, there were claims that it was never accurate from the start. Like another American camera, the Clarus MS-35, the Perfex series of cameras suffered a poor reputation as being unreliable and inferior to their German competition.

As a result, in 1948 the Fifty-Five was replaced with 3 new models, the Deluxe, One-O-One, and One-O-Two. The Deluxe had the same focal plane shutter and interchangeable lens mount as the Fifty-Five, but the other two models were lower cost models with Wollensak Alphax leaf shutters and a fixed lens mount. These changes allowed for the Perfex to be sold at a lower cost, and the well designed leaf shutter proved to be more reliable. It would seem though, that the Perfex’s reputation as an unreliable camera, plus the rise of the Japanese camera market killed any demand for the camera, and production ceased in 1950.

One year prior to the collapse of the Candid Camera Corporation, a revised model called the Cee-ay-35 was created with a more sophisticated body design, but it was too little too late. The design of the Cee-ay 35 was sold to fellow American company, Ciro, who rebadged the camera as the Ciro 35 and continued to make it for a few more years as an inexpensive American rangefinder.

I don’t know that today anyone collects Perfex cameras other than those like me who have a bit of American patriotism who want to revisit what the American camera industry was like after World War II. When I got this camera last year, I had the intent to do an “American Face-Off” article and compare it to other American cameras like the Argus C3, Clarus MS-35, and whatever else I could find. Although the Perfex One-O-Two that I picked up was in cosmetically very nice condition, it was completely inoperable. The shutter wouldn’t fire and someone previously had disassembled the lens and did not put it back together properly as the focus would just spin freely without engaging the rangefinder.

Further adding to my underwhelming opinion of the camera, the build quality of this camera feels cheap. Usually we tend to associate cheap things as being lightweight, but the Perfex is the opposite, its extremely heavy, almost to the point of being comical. It literally feels like a lead weight in your hands. Where most heavy cameras have a feeling of purposeful precision, the Perfex feels like a clumsy dumbbell and where many metal camera bodies can feel elegant and cool, the solid metal panels on this camera just feel cold like a cannonball in winter. The viewfinders are small and dim, and the lack of a functioning shutter just turned me off from any attempt to salvage it.

In reality, this is a pretty basic camera, and I do have some experience restoring Alphax shutters like the ones on my Argoflex EF, and Ciro-Flex. There is a chance I could revive this camera, but I’ve had it for nearly a year, and not once have I ever been excited about giving it a shot. This thing has literally just sat in a box for months, largely forgotten. When I was planning this article, this was actually the last camera I thought to include because frankly, I had forgotten about it. Who knows, maybe that’s the exact reason why I SHOULD revive it. If I could get this thing working and manage to get some shots from it, it could very well be my most underwhelming camera ever, and who knows, that might make for an interesting article!

For now, this remains a “Camera of the Dead” and I am happy to share what little I know about it with you!

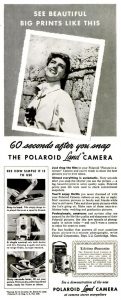

Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 (1948)

This is a Polaroid Land Camera model 95 which was designed by Dr. Edwin Land, and was the first successful implementation of a self-developing ‘instant’ film camera. Although other companies successfully marketed and sold instant cameras, the name “Polaroid” became synonymous with instant photography in the second half of the 20th century. The 95 is a very large camera that uses an early form of instant roll film that would be pulled from the camera one exposure at a time. Development time was a little over a minute which was slow by later instant film standards, but revolutionary when first introduced in 1948. The 95 used Polaroid 40-series film which was discontinued in 1992 and there are no modern equivalents to shoot with this camera. It is possible to modify the Land Camera model 95 to use other types of roll film or instant sheet film, but that’s not something that I have taken the time to do.

Film Type: Polaroid 40-series Instant roll film

Lens: 135mm Polaroid f/11 coated 3-elements

Focus: 4 ft to Infinity

Shutter: Polaroid Rotary Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/8 – 1/60

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M and X sync via ASA port and proprietary two pin connector

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/polaroid_pdf/polaroid_95a_95b_700.pdf

History

Although the company no longer makes cameras or film anymore, the name “Polaroid” is still widely recognized as a type of instant film camera much in the same way that any type of facial tissue is often called a “Kleenex”, or how photocopiers are often called “Xerox” machines regardless of who made them. If you were born prior to 1990, the chances are extremely high that at least once in your life, your photo was taken by a Polaroid camera.

How it all began is a pretty fascinating story, led primarily by an even more fascinating man, named Dr. Edwin Land who Wikipedia suggests was the Steve Jobs of the mid 20th century due to his visionary ideas and groundbreaking patents. Dr. Land once studied chemistry at Harvard University before dropping out of school after his freshman year to pursue development of polarizing light filters. Together with his Harvard physics instructor, George Wheelwright, they both formed the Land-Wheelright Laboratories in 1932. The company would later be renamed the Polaroid Corporation in 1937.

Polaroid’s original patents were for a light polarizing film called ‘Polaroid film’, which was used in the manufacturing of glare reducing sunglasses, 3D projection, and during WWII, night vision devices. In total, Dr. Land is credited with 533 US patents, which is second highest by any one person, only to Thomas Edison.

Polaroid was already quite successful by the end of World War II, but it wouldn’t be until 1948 that the company would release it’s most game changing product, the instant film camera. Like Kodak, Polaroid was a “film first” company and only made cameras as vessels to consume film. Polaroid’s instant film required a camera to use it, and as a result, the Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 was born. There is a rumor that the number “95” was chosen because that was the price the camera was said to sell for, but period advertisements show the camera often selling for right around $100, so I am not sure if that’s just a rumor of convenience, or true but prices just fluctuated more than the company intended.

Polaroid would outsource construction of the earliest Model 95s to other US companies like Wollensak, Bell & Howell, Samson United of Rochester, NY, and possibly even the Timex Corporation out of Atlanta, GA. The Model 95 used a new type of Polaroid instant film that would sandwich light sensitive negative and positive layers between a reagent chemical that when exposed to light, would transfer and develop an image from the negative to the positive side. The positive side would be removed from the camera and would serve as the photograph. The total time to develop an image was right around 1 minute, but would vary depending on outside temperature and film stock used.

The Polaroid Land Camera was extremely successful with the original model selling well over a million copies. In the decades that followed, Polaroid would release many different models and film formats, reaching the peak of their popularity in the late 1970s, with an estimated 21,000 employees and sales in the millions of units. Although functioning as CEO, Edwin Land considered himself first and foremost a scientist and inventor. He was also an avid humanitarian tackling often controversial issues such as employing women as research scientists and taking an active role in the affirmative action movement after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

Although Polaroid’s consumer cameras were the bread and butter of the company’s sales, their products consisted of more proprietary and sometimes very large room sized cameras. Polaroid’s largest film had an exposed size of 20 x 24 inches. Originally introduced in 1977 at the Polaroid share holder’s meeting, the massive 20×24 camera was a sliding view camera with huge red bellows, and shot massive 150 foot long rolls of film. A total of six 20×24 cameras were ever made and originally were intended to be used without charge, by artists who would only pay for the film, and the understanding that Polaroid could use the images.

Many famous artists and subjects have used or been photographed using 20×24 Polaroid film due to it’s massive size and instant results. There has been no other camera ever made with the size and instant gratification as the 20×24 Land Camera. Sadly, as of 2009 the film needed to use the 20×24 camera was discontinued, and existing supplies are expected to run out by early 2017 at which point, the last 20×24 image will ever be taken.

Dr. Edwin Land would run his company until his retirement in 1981 and although the Polaroid Corporation would live on in his absence, the company’s pioneering days of innovation would be over. Polaroid would stumble into the 21st century and would not survive the arrival of digital photography. In 2001, the original Polaroid Corporation would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and although a Polaroid holding corporation would continue to operate and make Polaroid film, the new company would cease all film manufacturing in 2009 relegating the Polaroid brand to a marketing name applied to various products made by other companies.

My Thoughts

Throughout my journey collecting old cameras, I can say that Polaroid cameras were just not something I ever had an interest in. For one, the film is very hard, if not “impossible” (heh, heh, get it?) to find. In addition, most Polaroid cameras aren’t very attractive and just never appealed to me. So, when this Land Camera fell into my lap, I thought it was kinda cool looking, and the fact that it was the original Model 95 from around 1948 meant that I could at least pride myself in owning a historically significant camera, even though I would likely never use it.

The camera sat in a the lower shelf of the liquor cabinet that I display my cameras in for months before realizing that it might make a good addition to my “Cameras of the Dead” series. Yet unlike every other camera in this series, this one actually works. The camera is in nice cosmetic shape, the bellows appear to be light tight, the shutter seems to work at all speeds, and the lens is free from fungus, haze, or major scratches.

Since I couldn’t use it however, I figured why not include it, so this began my efforts to throw together enough information to include it as an official “dead” camera. But a funny thing happened. As I handled the camera and looked at it enough to figure out how it might have worked, it’s bulbous size started to grow on me. The fake brown leather covering is quite nice. It has a very custom saddle tan appearance and texture that really compliments the brushed aluminum body. Whenever I review a camera, I generally take it out for some “glamour” shots for the review, but as I was photographing this camera, I started to grow more and more appreciative of it’s looks.

Then I read a little about it’s history and learned more about Edwin Land, and his contributions to photography, and how innovative the entire Polaroid company was, and before I knew it, I found myself fascinated with this thing. Sure, its a hulking whopper of a chunk of metal, but I can’t help but be amazed at how it was designed. This thing really is beautiful, and unlike most cameras where 5 – 6 shots are good enough for a review, I found myself with over 30 different shots that all looked great. I narrowed those down to just the best 14 and since this review isn’t long enough for me to scatter them throughout like I usually do, I decided to add a little gallery of the extra shots that I took.

Using the Camera

The Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 is an impressive device to look at, standing a full 24 cm (~9.5 inches) tall and weighing in at 1938 grams (~4.27 lbs), it is very large and very heavy. Much larger than any other folding camera I own.

The extra size was needed to house the complex system of rollers need for the instant film to work. Unlike “regular” roll film cameras that use light sensitive negative or positive film, the Polaroid needed to have both a positive and a negative sheet, with developing chemicals sandwiched between. To expose an image, the negative layer must first be separated and run across the film plane. Firing the shutter exposes the negative side of the film only.

Simply firing the shutter does not begin the development process. After firing the shutter, you must release a film catch, open a small metal door on the side of the camera which exposes a small paper tab which you pull out of the camera. Once you’ve pulled the paper tab out of the camera, you have moved the exposed negative to a position in which it has come in contact with the positive paper and development chemicals.

At this point you wait for the image to develop. Most film of the day took a full minute for the developing to complete, but this time varied with ambient temperature and with other types of film that became available over the years.

Once an adequate amount of time had elapsed, you would open a secondary door on the rear of the camera which exposes the back of the positive image. The positive image has perforations in the paper which you must tear with your fingers to separate the positive from the negative image. These perforations are why all Polaroid prints from this camera have a unique serrated edge to them.

If this sounds confusing, don’t worry, it is. The camera has a total of 3 doors to open for loading and unloading film. There are no shutter speeds or aperture numbers anywhere on the camera. Instead, there was a dial, numbered 1-8 that would change shutter speed and iris size to correspond to a variety of lighting situations.

This is definitely a camera in which you need to read the manual to familiarize yourself with before you even think about shooting with it (assuming film was available…which it’s not). But before you can do any of this, you need to load film in it.

Since film for these cameras is not made anymore, I can’t show you how to do it, since I’ve never done it myself. There are a few videos on Youtube that show how to load film into a 95 series Land Camera, but most of them are either very poorly recorded, blurry, or entirely in Russian. I found the following video below which is done on a Model 800 Land Camera which is very similar to the Model 95. The camera looks different, but they use the same film and load in a similar manner.

I’d love to explain more about how this fascinating camera worked, but without any film, its just not possible.

Since this is a camera from the dead, I wont have any images to show you, but I managed to run across a fellow camera enthusiast named Bernard Wilson who owned a Model 95 back in the 1970s and he offered to send me some scans of images he took with his.

Bernard granted me permission to share his images here, and since I can’t shoot my own, here are actual scans from what he describes as the late 1970s near Seattle, WA.

My Conclusions

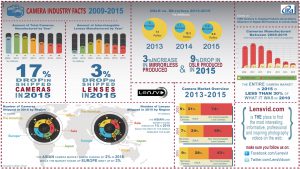

As anyone who collects or shoots film cameras knows, our hobby is dying. Even though there is the occasional story of some boutique new film emulsion being pandered around Kickstarter hinting at some film renaissance on the horizon, there’s just not a lot of evidence to support that the glory days will ever return. Kodak no longer makes any slide film, and they’ve discontinued the chemicals needed to develop Kodachrome films. In 2015, Kodak officially killed off the 220 format and earlier in 2016, the news broke that Fuji was discontinuing it’s popular peel-apart FP-100C Instant Film. It seems that every few months, something else is disappearing.

The problem isn’t even just with film. The entire digital camera industry is in a free fall as well. According to CIPA (the Camera and Imaging Products Association), sales of all cameras dropped to less than one third of it’s size from 2010 – 2015. In 2013 alone, sales of digital cameras dropped nearly 40% in just that one year. A lot of this can be explained by the proliferation of good camera sensors on modern smartphones. Since everyone has a pretty good digital camera on their phone, the need for a dedicated camera is a lot less than it was 5 years ago.

Digital mirrorless and reflex cameras haven’t seen the same massive drops as the industry as a whole, but even their sales are affected. Since hitting a high of 21 million units sold in 2012, that number has dropped to nearly 13 million units in 2015. While it’s expected that these drops will eventually stabilize, the camera industry as a whole will likely never again be as strong as it once was.

There are already many cameras like the Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 that will never be used again, and that list of dead cameras will likely continue to grow. We are already at a point where many of these fascinating devices exist only to remind us of the past.

If there’s one thing that’s becoming clear to me as I review more of these “dead” cameras, its that I have more of them than I realize. When visitors come to my house and see my china cabinet turned camera case, a common question is “Do all these work?” Previously, I would proudly proclaim that yes, they all work and I’ve been able to get images from them. I don’t normally display broken cameras, and if I do encounter one that’s in nice shape but isn’t operational, I’ll often try to sell it to get whatever little I can, for something else.

Some of these dead cameras are really cool, and my thoughts are similar to what I said in the first Cameras of the Dead article, which is that not every camera can be saved, but that doesn’t mean they’re not still worth something. People reading my site must think that I have a camera tree in my backyard that just grows working vintage glass, which couldn’t be farther than the truth. Even the best old cameras rarely work exactly how they were when they where new. The key is using them to their strengths. Maybe I limit them to specific shutter speeds, or maybe I have to take extra care to seal the bodies from light leaks, but in many cases, a less than perfect camera is still capable of making images.

I still love this hobby and I love hearing from other people who do too. If there’s one thing that I hope all of my reviews do, is to encourage people to use their cameras for their intended purpose while they still can. The film industry is a tiny fraction of what it once was, and while many old cameras are still usable, there’s no guarantee that will always be true. There is a real possibility that one day, every film camera might become a “Camera of the Dead”, and that’s really sad to me.

Thank you for putting these thoughts to words. On the bright side, today I’m ordering some Kodak Ektar 100 slide film for my Argus and Retinas, and there’s still B&W film available for Perfexes.

I wish someone would make film for these that produced an instant large negative.