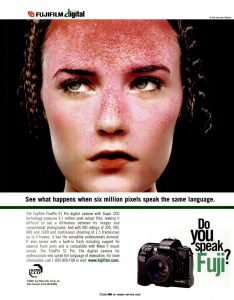

This is a Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro digital camera which uses the body of a Nikon N60 film camera and a Fuji digital camera system grafted onto the back. This was an early digital camera aimed at the high-end consumer market and although primitive by today’s standards, was a state of the art camera when released. Using Fuji’s own Super CCD sensor, it output 6.13 megapixel images at a time when 1 or 2 megapixels was the norm. It was the first time a digital camera offered state of the art technology at a price that was within reach of the average person.

Sensor Type: Fuji Super CCD APS-C 3.4 megapixels (interpolated to 6.13 megapixels)

Storage: CompactFlash Type II and Smart Media

Lens Mount: Nikon F-Mount Bayonet Mount

Lenses: Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 + many others

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Vertical Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 30 – 1/2000 seconds, stepless

Exposure Meter: 3D Matrix, Center-Weighted and Spot metered

Batteries: 2 x 3V CR123A Silver-Oxide or Lithium equivalent; 4 x 1.5v AA alkaline or NiMH; 1 x CR2025 button cell

Flash Mount: Hotshoe

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/FujifilmFinePixS1ProManual.pdf

History

One look at the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro and you can see that this is a franken-camera of a Nikon body, combined with a Fuji digital camera grafted onto the back. Although this was sold and marketed as a Fujifilm camera, the basic body, shutter, viewfinder, flash, and most of the electronics come from the Nikon N60/F60 which was sold between the years 1998 and 2001.

**** cue record scratch sound here ****

Wait a minute, did you say digital? Like as in a “digital camera”? What the heck is a digital camera review doing here? I thought you only reviewed film cameras on this site?

WTF

Okay, okay, you got me, despite it’s film camera DNA, the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro is a digital camera, but to be fair, I never said this site was film only! In fact, the types of cameras I’ve written about have evolved since my first review back in 2014. I never intended to review auto focus point and shoot cameras either, and look how that turned out! I review cameras that are interesting to me and those that have something worth talking about, and if you’ll stick with me for a while, I think you too will appreciate this camera and see why I thought it was worth inclusion here.

So, lets get back to some history.

History, Continued

The Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro is equal parts Fuji and Nikon. Since I’ve already typed up histories for both companies in my reviews for the Fujica 35-ML and various Nikon cameras, I’ll skip repeating some of that stuff here and talk instead, about a man named Steve Sasson.

The name Steve Sasson likely does not resonate with too many people. His role in the history of photography is not as well known as men like Louis Daguerre, George Eastman, Carl Zeiss, or Oskar Barnack. Yet, Mr. Sasson’s contributions to the world were just as important to photography as those other men. In December 1975, at the age of 24, and while working for Kodak, Steve Sasson created the world’s first digital camera.

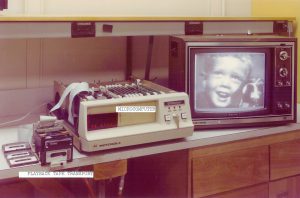

Like many pioneering designs, the first digital camera barely resembles anything of what we would today call a camera, but all of the necessary parts were there. It has a lens from some random Super 8mm camera, a parts-bin CCD image sensor, a digital to analog converter from a digital voltmeter, rechargeable nickel cadmium batteries for a power source, and an audio cassette recorder for storage.

Cobbled together in a basement lab using various circuit boards designed for other applications and a custom built aluminum chassis, Steve Sasson’s contraption captured a 0.01 megapixel black and white image, and wrote it to a run of the mill audio cassette tape. The entire image was captured in 50 milliseconds, but it would take 23 seconds for the image to be recorded to the tape. In order for it to be played back, it had to be read by a specially designed Motorola microcomputer and displayed on a television screen.

Steve Sasson would take his device and demo it multiple times to various executives at Kodak. After showing it off in one board room, he would be asked to show it off again to more executives, working his way up the chain to the highest ranking people working for Kodak at the time.

Both to Kodak’s credit and detriment, Kodak realized the potential of such a device. Here was something that could electronically capture images and play them back using no consumables, no film and no paper. The possibilities would be endless, so Kodak did the the most logical thing they could do with such a device…and hid it from the world to see.

Realizing that a digital camera system could spell the end for the film industry, Kodak knew that if the digital camera were to be mass produced, it would cannibalize the very market that Kodak depended on. The photography industry never made huge profits from the sales of cameras, the biggest profits were from the recurring sale of film and photographic paper. This new device would change all of that.

Over the course of the next 15 or so years, there were a few advancements in the world of digital photography, but most of them like the Sony Mavica used video based recording systems that would capture and digitize a single still image using NTSC or PAL video. Other companies like Canon, Toshiba, and even Nikon would dabble into the still video camera business, but none were considered true digital cameras as they used freeze frames of existing video standards as their method for capturing data. It wouldn’t be until the late 1980s before any new advancements would come that could actually be considered true digital photography, and once again, it would be Kodak who led the charge.

In 1987, Kodak would create the first solid state digital SLR camera that could capture megapixel images in a digital format. The Kodak Electro-Optic Digital Camera was designed in cooperation with the US Government as a way to capture digital images directly onto a magnetic storage medium. This camera used the body of a Canon New F1 film SLR and had a custom back with a 1.4 megapixel sensor, capable of 1340 x 1037 pixel images. The camera stored it’s images on a proprietary magnetic tape drive which was connected to the back of the camera using a ribbon cable. This camera was never sold the public and was created as a one off device. According to Jim McGarvey who was the lead designer of the Electro-Optic Digital Camera, only one was made and after delivering it, it was never seen again. Whether this camera still exists today in some closet of a secret government facility is anyone’s guess.

In 1989, it would be Steve Sasson again who would build the worlds first DSLR using a modern SLR body that wrote digitally compressed images to on board memory storage. The Kodak Ecam used a 1.2 megapixel sensor and was built into an entirely portable body that did not require a large storage device to be connected to the camera for it to work. Once again, Steve Sasson would demonstrate his new camera to the executives at Kodak, and once again, their reception was lukewarm.

Kodak would actually own patents for the name “digicam” and many of the technologies used in these early digital cameras. They would receive royalties by other companies for each new model made, and throughout the 1990s, would work in cooperation with other companies like Nikon and Canon building professional level digital SLRs, yet despite having a leg up on the entire world in the digital camera industry, Kodak failed to really embrace the technology, perhaps out of fear of cannibalizing the film market. A mistake that would ultimately lead to the company’s demise.

Throughout the 1990s, Kodak would release many commercially available digital cameras based off SLR bodies made by Nikon and Canon. The first was the DCS-100 from 1991 which used a heavily modified Nikon F3, and sold for the price of $30,000. It required the use of a shoulder mounted Data Storage Unit that contained a 200 MB hard drive and the power supply for the camera. While large and extremely expensive, the DCS-100 was a moderate success, selling nearly 1000 units, primarily to photojournalists who prioritized speed over quality. For the first time ever, an image could be captured in a remote location and electronically transferred back to the studio within minutes.

The Kodak DSC-200 followed in 1992 and was based off the Nikon N8080 film camera with digital electronics fitted to the back. Although it only offered a modest upgrade to a 1.5 megapixel sensor, it’s biggest advantage was that the body of the camera contained an 80 MB hard drive for local storage without the use of an external data storage unit. Although the capacity was less, it allowed for more freedom to use the camera without lugging around the storage unit.

As the 90s continued, new models would be released regularly with new advancements in speed and quality. Kodak was not only the market leader, but they had a near monopoly on the market as they owned the rights to many of the technologies in these cameras. Any attempts to compete in this market would produce profits for Kodak. Despite this success, all Kodak DCS series cameras were extremely expensive and were made in very low quantities. Kodak never saw the need to develop a new digital camera from the ground up, and even as late as 2004 with the release of the Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n, depended on existing camera bodies and lens platforms like those from Nikon and Canon.

In 1996, realizing that a new market was on the horizon, Nikon started work on what would become the world’s first consumer oriented digital camera designed by a single company. It would take three years to realize this vision, but in 1999, Nikon would release the D1. Featuring a 2.7 Megapixel sensor and offering up to 4.5 fps of continuous shooting and supporting the entire range of Nikon F-mount lenses, the D1 took the world by storm. Selling for a list price of $5,500 body only, it was expensive by today’s standards, but was a bargain compared to Kodak’s DCS series cameras that sold for tens of thousands of dollars.

For the first time ever, existing photographers had an upgrade path from film to digital using existing lenses and accessories for a price that was somewhat affordable. While still out of the reach of the average consumer, the Nikon D1 was a huge success.

As the 2000s continued, Nikon would continue to build upon the success of the D1 releasing more and more models that were better and cheaper than the models that preceded them. In less than a decade, nearly everyone would have a digital camera, and the film industry would practically collapse. Kodak, who had been at the forefront of the digital camera world since the mid 70s, and had released many of the first successful models, would fail to capitalize on this new technology, a mistake that would lead them to bankruptcy in 2012.

With Nikon leading the charge of third party companies in the digital world, other companies jumped in with their own technologies. One of those companies was Fuji who, like Kodak, was a world leader in photographic film, but perhaps to their credit saw the rise of the digital revolution coming better than their American counterparts. Fuji had been investing in CCD technology as far back as the 1970s, and by the 1990s, would develop a range of successful CCD sensors that were used by a variety of companies in early digital cameras.

Fuji’s first attempt at a digital SLR came in 1995 when they released the Fujix DS-505. It had a list price of $12,780 and like the Kodak DCS series, was developed in cooperation with Nikon. Also known as the Nikon E2, the DS-505 had a 1.2 megapixel sensor and accepted all Nikon F-mount lenses. The DS-505 would forge a partnership between Nikon and Fuji that would last over a decade and would allow both companies to be successful in the digital camera market. Fuji benefited from Nikon’s extensive selection of available lenses along with their quality bodies and shutter systems. Nikon benefited from Fuji’s knowledge in CCD and digital camera design.

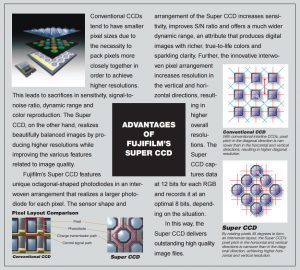

In 2000, after the release of Nikon’s D1, Nikon and Fuji would release the first pro-sumer digital SLR series known as the FinePix S-series. Marketed only as a Fujifilm model, the first model in the series, the S1 Pro was based off the Nikon N60 from 1998 and had Fuji’s new Super CCD sensor that used octagon shaped pixels oriented diagonally, compared to horizontal like every other sensor. I won’t pretend to fully understand how it worked, but if you want to read a technical explanation, here is a good article explaining it.

The Super CCD sensor claimed to offer two primary advantages. By orienting the pixels in a honeycomb fashion, you are maximizing the space in which the pixels are oriented. This allows them to be closer together and allow for more sensitivity in low light. It also had the effect of being able to increase the output resolution of the camera’s images allowing for larger images than those available using traditional CCD sensors. The Super CCD sensor in the S1 Pro was physically 3.4 MP, but after processing, would output images with a resolution of 3040 x 2016, or 6.13 megapixels.

Higher megapixels and honeycomb Super CCDs sounded pretty cool in the press release for the FinePix S1 Pro, but the thing people liked best was that it’s list price was “only” $3995, offering one of the best DSLR bargains of the time. Today, “bargain” is a relative term as $3995 translates to $5600 when adjusted for inflation.

Since the FinePix S1 Pro and Nikon D1 were both sold at the same time and both used Nikon bodies, many reviewers of the era put the two in head to head comparisons. Despite the word “Pro” in the Fujifilm’s name, the D1 was the more professional camera, offering a much more rugged body with improved dust and weather sealing, faster continuous shooting, faster and more accurate auto focus, and a $1500 higher price.

The Super CCD sensor was considered state of the art at the time, and in addition to it’s higher resolution, also offered higher sensitivity for low light images, than what was available by other companies. Upon it’s release, the S1 Pro had a user selectable range of ISO 320 – 1600 speeds. When used with a flash and fast Nikkor lenses, the S1 Pro was a very capable low light digital camera popular with wedding photographers.

Nikon and Fuji would simultaneously release their own unique models separate from one another, but they would maintain their partnership with the S-series through 2009 with the S5 Pro.

I could never find any sales numbers for the S1 Pro, or the entire S-series for that matter, but considering they were offered over the course of a whole decade, I have to think they were successful. Fuji would never reach a leadership position in the DSLR market, but their line of compact and mirrorless cameras would be highly successful. Nikon on the other hand would represent the pinnacle of DSLR development and sales. Today, both Nikon and Fujifilm are at, or near the top of their respective markets. Nikon has many different highly successful DSLR models from the professional D5 down to the entry level D3400. Fuji has the Fujifilm X-series, which is often mentioned among the most sought after mirrorless models.

In a sad twist of fate, Kodak, once the largest name in photography and the early leader of the digital camera era doesn’t make cameras anymore. Although the company name is still around and there exist cameras with Kodak names on them, they are all made by a third party entity called JK Imaging LTD. I can’t help but wonder what would have happened if Kodak had more visionary leaders, like a Kodak Steve Jobs. What would the landscape of photography look like today if Kodak had embraced Steve Sasson’s 1975 prototype, or even the Ecam from 1989? We can only wonder.

My Thoughts

It’s kind of funny to think that we have reached a point where there is such a thing as a “vintage digital camera”. I mean come on, these are things that were created after I graduated from high school! I’m not that old, am I?

If the appeal of shooting an old film camera is stepping into the shoes of photographers from the past and experiencing the challenges of shooting those models, shooting an old digital camera brings with it a whole slew of unexpected challenges as well.

In some cases, shooting a 17 year old digital camera might even be MORE difficult than shooting an 80 year old film camera because of the dependencies needed to make these gadgets work. You will likely run into a variety of technical hurdles with an old digital camera like finding a working battery or memory card, and finding a way to get the images off the camera onto a PC or some other device to use them.

Classic cameras with mechanical shutters don’t need batteries or any type of power, and assuming the camera is in physically good condition, should work just as good as the day it was made. Batteries on the other hand have finite life spans, and while many digital cameras used common AA and AAA batteries, many did not. My current DSLR, the Nikon D7000 uses a Nikon EN-EL15 Lithium Ion battery pack that likely will not be around in 50, 20, or even 10 years from now.

35mm film hasn’t changed much since 1934 when it was created, and 120 format rollfilm is even older, going unchanged since the first Kodak No.2 Brownie of 1901. Yet the storage mediums for digital cameras rely on an ever changing standard for memory cards. Early digital cameras from the 90s stored data on proprietary hard drives and data storage units. Later models used 3.5″ floppy discs, and by the time the idea of flash memory was widely used, many different variants of storage with names like SmartMedia, CompactFlash, xD, MemoryStick, SD, miniSD, and microSD have all been used. Today, more and more cameras are equipped with Wi-Fi to wirelessly upload images to the cloud or other social media services. While I’m sure this seems neat now, I worry about the viability of these wireless technologies in the years to come.

For the types of memory cards like CompactFlash which are still used today, the amount of storage supported by older digital cameras is far less than what you can buy today. A quick search for “CompactFlash” on Amazon returns cards as big as 128 GB with 32 GB cards selling for as little as $25. When the FinePix S1 Pro was released, the largest CompactFlash cards were 128 MB! For you binary challenged folks out there, 32 GB is 256 times larger than 128 MB! Finding a compatible 128 MB Compact Flash card today can be a challenge, and simply using a modern card does not guarantee the camera will be able to write to the significantly larger card.

Regarding batteries, the FinePix S1 Pro thankfully does not use any type of proprietary lithium-ion battery pack. But it does require the use of no less than 7, yes SEVEN batteries. Since the camera is based off the body of the Nikon N60, the N60 part of the camera uses 2 CR123A lithium batteries for the “camera part”. On the bottom of the camera is a second battery compartment for 4 AA batteries which power the digital part of the camera. The manual for the S1 Pro recommends against using NiCd batteries, but I’ve found that modern NiMH batteries work just fine. Finally, there is a CR2025 button cell battery nestled in a third compartment which is required to maintain the memory for things like the date and camera settings.

For storage, there are two options available. The first is SmartMedia which was a consumer oriented flash memory standard that went out of popularity in the mid 00s and is very hard to come by today. Thankfully, CompactFlash cards are still in widespread use and I was able to find one that worked. I used an 8 GB Sandisk card in the S1 Pro and while the camera had no problem reading it, it seems like the storage is capped at 2 GB.

In terms of getting the data off the camera and onto a computer, I had two choices. The first was to get an external CompactFlash reader, or try to find a USB cable that would allow me to connect the camera directly to my PC. I went the USB route since CF readers are over $20 today and I was able to locate an appropriate USB cable for $5 online. It’s worth noting that Fujifilm used a proprietary USB connector on this camera which I had to special order online. Whatever standard was used back in 2000 is no longer in use as the plug is not the same size as either microUSB or miniUSB.

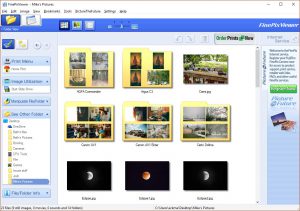

Armed with 7 batteries, a working CF card, and my proprietary USB cable, I thought I was ready to roll, until the first time I plugged the camera into the USB port of my Windows 10 desktop and nothing happened. I tried the usual steps needed to connect legacy hardware to a modern PC and I could not find any drivers that would recognize this camera. I searched Fujifilm’s website looking for drivers and I thought I had quickly found them, until I realized that Fujifilm has since reused the FinePix name and has a much more modern camera called the Fujifilm FinePix S1 from 2014. Trying to find software for the older SLR from 2000 proved to be a bit of a challenge.

Thankfully, Fujifilm has maintained support for their older FinePix software and lists it as compatible for operating systems as recent as Windows Vista. While Windows Vista itself is a 10 year old operating system, thankfully the program installed in Windows 10 without any issues. After the program was installed, the computer would instantly recognize the camera as an external USB drive. To Fujifilm’s credit, their software seemed to work pretty well and allowed me to view the stored images on the camera’s CF card, but I found the software to be painfully slow. I preferred instead, to just browse through the DCIM folder on the camera and copy the JPGs directly to my PC.

Now that the camera was fully working and ready to go, I was able to go out and shoot with it. In the unlikely event the pictures in this article don’t make it obvious, this is quite a large camera. Not pro level D5 with extended battery grip installed large, but it’s certainly larger than most modern mid range DSLRs. With all 7 batteries installed, a memory card, and the same Nikkor 28-80mm lens as pictured at the top of this review, the entire camera weighs 1179 grams which is a weight you’d certainly notice hanging from your neck all day.

Despite it’s large size, the ergonomics of the camera are quite good. Thankfully, the N60 from which it was based had a design from the modern era. I’ve never held an actual N60 before, but it’s the little brother to the otherwise excellent N80 which I have reviewed. The right hand grip is large and comfortable. The shutter release is located in the perfect location, and all essential functions are exactly where you’d expect them to be which is quite amazing considering this camera is already 17 years old.

A compromise of the FinePix S1 Pro that becomes immediately evident the moment you put it to your eye is that this camera was designed to shoot film with a viewfinder that covers a “full frame” 24mm x 36mm film negative, yet the digital sensor is a APS-C sized “crop” sensor. On DSLRs like my D7000 that were designed from the ground up to use APS-C sensors, the viewfinder is designed in a way that the full size of the smaller exposed image fills the entire viewfinder. Since the viewfinder on the original N60 was designed to show a full frame image, Fujifilm was forced to put some kind of baffle inside of the viewfinder to reduce the viewfinder image to only show an APS-C sized window. Not only does this make the image small, it also looks out of place with the built in LCD screen inside of the viewfinder which has a large black gap of nothingness below the visible image and where the viewfinder LCD was on the original N60. It’s a bit easier if I just show you a picture, so look at the image to the left of the FinePix S1 Pro compared to a Nikon N90s viewfinder.

A word about lens compatibility is that while the FinePix S1 Pro has a Nikon F mount that can mount any lens that the original N60 would have accepted (meaning almost everything except Non-Ai lenses), there are some exceptions. Modern AF-S lenses that rely on electronically controlled focus motors will not autofocus on the FinePix S1 Pro. They can still be used, but only in manual focus mode. Also, this camera uses an APS-C crop sensor which means that any full frame lens you mount to the camera will only use the center portion of the lens’s coverage. You will have to multiply the focal length of full frame lenses by 1.5 in order to get an equivalent focal length on the FinePix S1 Pro. A 50mm Nikkor AF lens produces images comparable to those shot with a 75mm lens on film. Nikon had just barely started releasing their new DX lenses in 2000, so there wasn’t much of a selection back then, but today, you could swap those lenses from more modern Nikon DX SLRs with the S1 Pro to maintain an equal focal length.

My Results

As much as I love classic cameras and shooting film, there is one undeniable advantage to digital that film will never match, which is convenience. In the early days of digital, film photographers would thumb their noses at digital photographers because shooting and developing your own film was supposed to be part of the process, but even if you love the process (and smells) of developing your own film, sometimes you just don’t have the time. Connecting a cord from your camera to a PC and immediately being able to see your results is truly the best thing about digital.

So while I have no intention to stop shooting film, and in some ways, NOT having that instant gratification can be a good thing, it was nice to be able to see my results immediately when using the FinePix S1 Pro.

I’ll start out with my most obvious observation which is that these images look fantastic. The images are bright and colorful and show great clarity. Fuji clearly spent a lot of time on color calibration and accuracy. Perhaps it was their background as a maker of film, that inspired them to put a lot of effort into the Super CCD sensor’s ability to capture color. When I think of how far digital photography has come in the last decade and a half, I fully expected that these images would look far worse.

In 2001, I bought my first digital camera, a 2.2 megapixel Toshiba PDR-M25. Looking back at the images I took with that camera, they consistently exhibited washed out colors, blown out highlights, and murky shadows. Most images suffered from a lot of noise, even at low ISO settings. Generally speaking, my experiences with digital photography in those early years wasn’t so great but that was OK because it was a new frontier of technology. The loss of quality was more than made up for the convenience of not having to develop film.

The image to the right is an actual photo I shot in the summer of 2002 using that Toshiba digital camera. Notice the lack of sharpness and vibrancy in the photos. The whites of the tent are completely blown out, yet the shadows of the band members are murky and show quite a bit of noise. This image is characteristic of many consumer level digital cameras from the early 2000s.

It seems now that there was a clear divide between the quality of those early “consumer” level cameras compared to what the pros were using at the time. It makes perfect sense since I likely wouldn’t have paid more than a couple hundred dollars for that first camera, when models like the FinePix S1 Pro were selling for well over $4000 when equipped with lenses.

It is clear that whatever weaknesses this 17 year old camera has, its not with the quality of the images. I found the overall images to be well defined, vibrant, and highly detailed. The 6.1 MP output of the Super CCD sensor makes images with a resolution of 3040 x 2016. This is nearly identical to the high-resolution 35mm scans that you would get from an online lab like Dwayne’s Photo which are usually around 3089 x 2048.

When I blow up these images and look at them at 100%, they have a tad bit of softness to them that gives an almost film like look to them. Printing 4×6 or 5×7 images taken with this camera would certainly not show any of this softness, but the more you zoom into them, there is a level of detail lost when compared to a modern DSLR. I tried changing the detail settings in the camera’s menu and even tried the TIF output setting and never noticed any difference when it came to this softness. Sadly, the FinePix S1 Pro does not offer the ability to create RAW files.

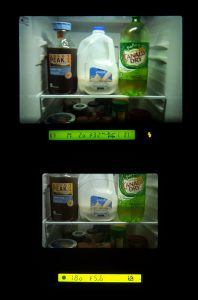

The image to the left shows the same scene using a Nikon D7000 (top) and both a JPG and TIF from the FinePix S1 Pro using the same Nikkor AF 50/1.8 lens and same SB-600 speedlight. In both cases, each camera was in aperture priority mode at f/8, ISO was set to 320, and the white balance was set to Auto. In the case of the Nikon D7000, I resized the image to match the resolution of a 6.1 megapixel image in Photoshop. No other editing was done. Click the image to the left to see the full resolution in your browser.

The image to the left shows the same scene using a Nikon D7000 (top) and both a JPG and TIF from the FinePix S1 Pro using the same Nikkor AF 50/1.8 lens and same SB-600 speedlight. In both cases, each camera was in aperture priority mode at f/8, ISO was set to 320, and the white balance was set to Auto. In the case of the Nikon D7000, I resized the image to match the resolution of a 6.1 megapixel image in Photoshop. No other editing was done. Click the image to the left to see the full resolution in your browser.

Looking at the Exakta logo in the center, the detail in the D7000’s image, even when downsized, is clearly superior. The TIF didn’t seem to help much, although if I stare long enough, I barely see an ever so slight improvement in clarity in the TIF. Also notice that the white balance of the D7000 favored a cooler, more natural tone, whereas the FinePix S1 Pro took on a warmer tone.

The FinePix S1 Pro’s lowest ISO setting is 320 and the majority of the images in the gallery above were shot at either that setting or the next lowest, which is ISO 400. They show almost none of the noise visible in shots taken with low end digital cameras from the early 21st century.

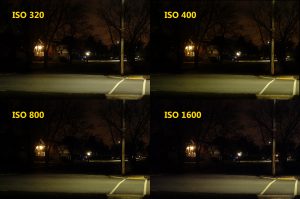

What’s even more amazing is how well the Super CCD sensor performed in low light. I recreated the nighttime street shot in the gallery above at all 4 ISO settings this camera is capable of, 320, 400, 800, and 1600. Click the image to the right to see the full resolution in your browser.

ISO 320 and 400 are so close that there really isn’t any perceptible difference. At ISO 800, some noise is evident, but it seems more consistent with the natural grain of an ISO 800 film, rather than the excessive chroma noise seen on low end digital cameras. Bumping it to ISO 1600 increases the noise quite a bit, but it is still within the realm of what most people would consider a usable shot. There is enough detail to make out each spindle in the handrail of the house on the left, or to read “211th St” in the street sign.

I had planned on including a comparison of this same shot using the camera on my Samsung Galaxy S6, but it was so terrible, it wasn’t worth sharing. Trust me when I say the FinePix S1 Pro at ISO 1600 is leaps and bounds better than a current smartphone’s camera in low light.

Where the FinePix S1 Pro seemed to struggle is in white balance. I left the camera’s white balance setting at Auto for all of the above shots, and in every instance other than in bright sunlight, the images had a consistent blue or reddish cast to them. Modern CFL and LED light bulbs seemed to trick the camera the most, as almost every interior shot I took had a pinkish orange cast to them. Most of the images in the gallery above had some level of color balance tweak made to them in Photoshop. To the left is an example of the image of the little boy coloring before I made any adjustments to it. It’s worth noting that the camera does offer a Custom WB setting in one of it’s menus, which I did not explore. Perhaps I could have compensated for this with additional tweaks.

Thankfully, white balance issues are pretty easy to correct in post processing, and I’ll at least acknowledge that white balance was a pretty new concept to camera makers in the early 00s. My guess is many of the early digital cameras had trouble with this.

I could probably come up with a few other nitpicks of this camera, but they’re all pretty minor. There is a slight delay in between each shot where the shutter cycles and writes the image to the memory card. The delay is certainly in line with modern smartphones or point and shoot digital cameras, but is slow when compared to a modern DSLR which has an almost instant response time. I also noticed a strange quirk where the camera will give an Error on the top LCD whenever I would change lenses with the power on. I would have to always power cycle the camera after every lens change. This is not necessary on any other electronic Nikon I own.

Perhaps the biggest nitpick is that while using the FinePix S1 Pro, you will be constantly reminded that this is two distinct products made by two different companies, merged together. The Nikon part of the camera works and feels like a Nikon. The popup flash, top LCD, viewfinder, and all buttons on the top and front of the camera all work exactly like you would expect on any number of Nikon SLRs, however, the back of the camera is purely Fujifilm.

There is a total of 3 LCD screens on this camera, two of which are on the back. The first is a monochrome LCD panel with an orange back light that shows information like how many exposures are left on the memory card, your selected ISO setting, date and time, and a battery life indicator of the 4 AA batteries for the digital half of the camera. There are additional buttons for changing settings like white balance, image quality, JPG/TIF, and a few other options. When viewing images stored on the color LCD screen, this screen can be used to view EXIF data from the stored images.

Beneath this monochrome LCD is a 2.0″, 200,000 pixel color screen used to review images stored on the camera’s memory card. If you press the “MENU/EXE” button next to the directional pad, you get a second setup menu for additional camera settings like changing the language of the menus, setting the date and time, formatting the memory card, and defining which memory cards to use.

This is all in addition to the LCD on top of the camera which shows the battery life of the two CR123A batteries in the Nikon hand grip, along with “normal” camera things like shooting mode, shutter speed, aperture size, +/- EV compensation, and flash settings.

Conclusion

I mentioned earlier in this review that shooting a “vintage” digital camera can sometimes be more challenging than shooting an old film camera, and with 7 batteries scattered across 3 different battery compartments, 3 LCD screens with two different setup menus, 2 different battery meters, and a viewfinder that’s much smaller than those found in modern DSLRs, the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro is definitely more challenging than just any ordinary film camera. None of this takes into account the extra hoops that you must jump through in order to find a memory storage solution and the software and drivers necessary to transfer the digital images to a PC.

Consider that as I write this, its “only” 2017. What kind of hoops will be necessary 20, 50, or even 100 years from now? I’ve made great shots using cameras over a century old using film I bought online and I didn’t need to worry about USB connectors, battery compatibility, or drivers. What kinds of computers will we have 100 years from now? Will alkaline or lithium batteries even exist in the future or will they be outlawed like mercury batteries have been? Will future computers even be able to read the digital JPG data from modern digital cameras? There is a very real possibility that a day will come where mechanical film cameras are still usable whereas examples like this from the early 2000s aren’t.

In my time with this camera, I found it to be an enjoyable experience. I was impressed with the image quality and found it to be a lot better than I had expected. If you consider that any picture shared to social media, or posted on most websites is heavily resized, that you could share images with this camera side by side with those taken with a state of the art professional camera from 2017, and the majority of people would never notice the difference.

While the FinePix S1 Pro’s digital images don’t compare to modern DSLRs, they don’t need to be, and in fact were downright impressive to photographers back in 2000 – 01. The following are links to some period reviews of this camera when it was first released. There is almost unanimous praise, and in all of these reviews, the image quality, color accuracy, and ease of use were championed as the best features of the camera.

American Photo Magazine: Mar – Apr 2001

American Photo Magazine: Jul – Aug 2001

I found the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro to be a fascinating camera, and while I already have a clearly superior DSLR in my D7000, and its not one I’ll use often, I am glad to have it in my collection. I feel like this is one of the more historically significant cameras in my collection as it represents the exact moment that digital cameras started to become relevant. The mere fact that it’s images look anywhere close to what we get out of modern cameras is truly an achievement. I think you could show any of the images from my gallery above to 100 people and ask them to guess how old the camera was that shot them, and not a single one would guess 17 years old.

I think 2001 was the year that the rapid rise of digital photography started. It might have taken a few more years for the sales figures to prove it, but when I see the images that the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro were able to make back then, I can say with absolute confidence that digital photography owes at least some of it’s current success to models like this.

A lovely review of a lovely camera!

I have one and quite honestly its one of the best camera s I have owned! The only thing that keeps it from being the best is its inability to shoot in RAW and base iso of 320. That being said the jpegs are class leading in its own way even today after about 18 years of its introduction! The megapixels may be low but the clarity of the images are mind blowing (we are talking its base iso320!!). the high megapixel, high iso, muddy CMOS sensors are certainly no match! Period.

One has to use it to know what’s its all about. Its easy to have never tried and neglect it.

Its a gem and nowadays its rare too, hence people who appreciate it, have it. Cheers

Thanks for such a detail review! I manged to pick one of these cameras up recently. I am a Nikon shooter and I found it interesting that it was a F mount camera. I have the batteries required for this camera, hopefully it all still works.

Glad you liked the review. I also have a FinePix S5 Pro which is an even better camera, but I’ve never written about it. Both are still very capable cameras today!

I received this same camera from my brother for helping him through cancer treatment. He is a professional photographer and said that the S1 Pro was one of his favorite and state of the art at the time. It was pretty beat up from heavy use, however, I have been able to cannibalize a broken model I bought for $28. It is working great now, however, I can’t find a current model telephoto lens that will work on automatic focus. Any recommendations?

Keith, the S1 Pro requires D-type Nikkor AF lenses to support all of the exposure and auto focus modes of the camera. You can still mount earlier AF lenses, but the AF function won’t work as the earlier lenses required a drive pin from the camera body itself to focus the lens. In my review is a link to the S1 Pro’s manual and on page 107 is a chart explaining which lenses you can and cannot use. I highly recommend checking that out.

Perfect, thanks! I wasn’t sure what Focus aids meant. Looks like AF D is what I should stick with.

Hi Mike. Your lens spec worked perfect, got a great used Tamron 70-300, I could use your help again. I tried to use a Verbatim 2Mb CF with no luck. I had the camera format the card, I tried formatting FAT16 from my computer through a card reader. The card will hold images copied to if from the PC, and will display them in the camera (play). Unfortunately, when i try to record a picture from the camera, the REC.in the display just flashes forever. It sounded like you had success with Compactflash. Can you help me pick the correct card or process? Thanks, Keith

I ordered a 1gb Sandisk CF SDCFB, and it worked perfectly. Thanks Keith.

Keith, glad you got that card working. I didn’t get a chance to respond in time, but I was going to say that the S1 Pro is definitely picky about which cards it works with. I had to try a couple different kinds before I found one that worked too.

That was an interesting review, thanks. And yes, it’s crazy to think that getting the images out of the early Kodak DCS models is already nigh-impossible, whereas a century old 120 folder can produce lovely prints without much effort in 2020.

Hi

Great post….great to read about the cameras history. Have a S1 and S2 and a number of nikon lenses. Love the tones and colour reproduction. I bought both cameras second hand, without accompanying software. really want to try the Hyper-Utility, especially remote shooting. Frustratingly I can only find upgrades. Can anyone direct me to somewhere where I can get S1/S2 utilities. It would be greatly appreciated. Thanking you in advance. PeterL