This is a Miranda Sensorex 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Miranda Camera of Japan between the years 1966 to 1972. The Sensorex was a semi-professional SLR camera that aimed to be an alternative to more expensive professional cameras made by Nikon and Topcon, offering similar features, but at a fraction of the cost. The Sensorex is a fully featured camera with a TTL CdS exposure meter, interchangeable viewfinders, dual bayonet/screw lens mount, and a quiet vibration free shutter. Although competitive on paper, the Sensorex, like most Miranda cameras, failed to succeed in the marketplace, and by the 1970s, the company quickly fell into disarray, eventually resulting in bankruptcy by 1977.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

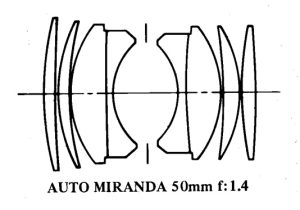

Lens: 50mm f/1.4 Auto Miranda coated 8-elements (!)

Lens Mount: Miranda Bayonet and 44mm Screw Mount

Focus: 17 inches (0.43 meters) to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL CdS Meter w/ Viewfinder match needle

Battery: PX625 1.35v Mercury Cell

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1096 grams (w/ lens), 753 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/miranda_pdf/miranda_sensorex_c.pdf

How these ratings work |

At one point in time, the Miranda Sensorex was seen as a viable low cost option to pro cameras like the Nikon F and Topcon RE Super. Although it shared a similar feature set, and an available selection of excellent lenses, quality control proved to be the company’s undoing. Finding a nice Sensorex in good working condition today is difficult, but if you are lucky enough, they are very nice cameras with a lot of heft, and excellent ergonomics. It took me years to find one in good enough condition to get through a roll of film without failure, and I am happy to say the wait was worth it. YMMV however. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

In the mid 1960s, if you were in the market for a professional 35mm SLR camera, you basically had two options, the Nikon F or the Topcon RE Super. Other companies like Canon and Minolta had their advanced cameras for sure, but they lacked features like interchangeable viewfinders and TTL Open Aperture metering.

Never one to miss a chance to release a near-professional level camera at a discount, in 1966 the Miranda Camera Company released the Sensorex, their new top of the line model with all of those features. The Sensorex was a continuation of Miranda’s earlier Automex line of cameras first introduced in 1960. The Automex had a completely redesigned body from previous Miranda cameras and contained a large selenium exposure meter on the front of the prism above the lens mount. It was a well built and ambitious camera by one of the smaller Japanese camera makers.

During this time, Miranda had a very strong relationship with an American import company called Allied Impex Corporation (AIC) that handled exclusive sales of all Miranda cameras outside of Japan. In a letter written by an ex-AIC employee named Lee Mannhemier from a now-defunct Geocities website, Mr. Mannheimer paints a bleak picture of what it was like to work for AIC when he was there. Although his employment started in 1969 and doesn’t give specific details about the early relationship between his company and Miranda, he suggests that AIC’s management had a heavy hand in the day to day operations at Miranda.

There was a Japanese law forbidding foreign ownership of Japanese companies, so this likely caused problems for Miranda in their own domestic market, which may or may not have been responsible for the near exclusive export arrangement for their products. I cannot find any evidence of Miranda cameras sold directly to the Japanese market at this time.

According to a 1961 Sears catalog, the Automex had a retail price of $299.99 which priced it just below the Nikon F at $329.50 but offered a built in light meter which the Nikon lacked. Whether or not the Automex was a United States exclusive camera is anyone’s guess, but it sold well enough to continue the line. The Automex would see two revisions, called the Automex II and III with the last having a body-mounted CdS exposure meter.

In 1966 Miranda would move the exposure meter inside of the body for TTL metering and add the capability of open aperture metering. This required an externally coupled revision to the Miranda lens mount adding an external arm that would couple to a ring around the body so that the camera had a way of knowing which aperture was selected on the lens. Miranda’s choice of an external coupling was very similar to Nippon Kogaku’s approach of the ‘bunny ears’ seen on early Nikkor lenses. Miranda’s coupling arm was better designed than the one on the Nikon as it required no additional steps when mounting the lens to calibrate the position of the coupling, but also like Nippon Kogaku’s system, it was incompatible with earlier Miranda lenses that lacked this arm.

The Sensorex used the same basic body design as the Automex, replacing the space occupied by the large selenium meter with a black and chrome trimmed decorative plate that somewhat resembles the front grille of a pickup truck. The Sensorex was not only the top of the line in Miranda’s line-up at the time, but would also become a pinnacle of sorts for the brand.

The Sensorex sold well and was generally well received. In 1966 it had a retail price of $249.50 with a 50mm f/1.9 lens which was a considerable discount from competing models like the Topcon RE which had a list price of $369. In an attempt to further lure photographers to a relatively small brand like Miranda, all Sensorexes had industry-leading 3 year factory warranties, something that was often mentioned in Miranda’s advertisements.

Take a look at the gallery below of 12 different advertisements I found for the camera. In my research for reviews on this site, I don’t always find this many ads for a single model, but the vast number of them available suggest that Allied Impex spared no expense in trying to get the word out about this model.

In an article written by Arthur Kramer from the April/May 1967 issue of Camera 35 magazine, Kramer is clearly impressed with the feature set and usability of the Sensorex. Marveling at how well the camera’s controls are laid out, he mentions that the camera can be easily used while wearing bulky gloves. The front shutter release and large shutter speed dial were easy to change with gloves on. The large and bright viewfinder with microprism circle and match needle exposure system also received positive remarks.

Throughout their history, Miranda regularly updated their models and replaced older models with revised ones on an almost annual basis, but the Sensorex was continuously available from 1966 to 1972 at which time it was replaced by a cheaper Sensorex II. In 1970, a slightly revised Sensorex became available known as the Sensorex-C which added a flash accessory shoe to the top of the standard prism and eliminated the removable back, replacing it with a fixed back. Although called the Sensorex-C in the revised camera’s user manual and in product documentation, it was never indicated anywhere on the camera.

At the same time of the Sensorex-C’s release, a new 8-element Miranda 50mm f/1.4 lens became optionally available. It was of Gauss design and featured a “Spectrahard” coating to assure perfect color rendition. This new 8-element lens was a behemoth of a lens, and weighed 343 grams (12.1 oz) by itself. Miranda never made their own lenses, instead outsourcing their construction to third party companies. I could never find a manufacturer who built this lens, but some names that often get tossed around when it comes to Miranda lenses were Zunow, Kowa, Ofuna, and Tamron. Whether this lens was made by any of these companies is anyone’s guess, however.

Sadly, due to mismanagement of the company and a change in the camera marketplace, Miranda’s cameras began to suffer from poor quality control. Later models were built to lower quality control standards, and their reputation for reliability took a nose dive. Although they would continue to release competitively priced SLRs until the mid 1970s, the company would eventually go bankrupt. The Sensorex would not only be the company’s best selling model, but would signal the beginning of the end for the company.

My Thoughts

In what has been the longest review it’s ever taken me to write, I acquired my first Sensorex in the spring of 2015 and had planned on writing a review of it back then, but continual problems with that first camera and all subsequent others I came across doomed this article into what seemed like a never ending draft status.

But here we are in February 2019, nearly 4 years after I picked up my first Sensorex and I finally have something worth writing about. This journey wasn’t easy, as I’ve come across no less than 4 different Sensorexes (I actually think there’s been 5, but it’s hard to keep track). I’ve had film pressure plate failures, multiple shutter failures, reflex mirror failures, and one whose lens inexplicably missed focus on literally every shot despite the image looking correct in the viewfinder. One time, I contributed to the camera’s demise myself by letting it fall out of a bag onto a cement floor, denting the pentaprism.

It’s hard to keep coming back to the same camera over and over again but for whatever reason, I continued to be enamored by the Sensorex’s good looks. It didn’t help that I also came across other working Mirandas, namely the Mirandas A and D which both worked fine so this model never really strayed far from my mind.

I actually shot this particular example twice, the first being the one I mentioned earlier was the one where every image came out of focus even though the image in the viewfinder looked sharp. I initially thought something was wrong with the lens so I tried a number of other Miranda lenses and using a piece of ground glass in the film gate, I could see everything was out of focus. That’s when I shifted my attention to the viewfinder. The Miranda’s interchangeable viewfinder helped me in that I could easily gain access to the focusing screen by disassembling it from the top.

I’ll spare you the details, but having other broken Sensorexes with good viewfinders, I was able to ascertain that someone had opened this camera up at some point in it’s life and obviously didn’t put it back together. Rather than piece meal individual parts from one camera to another, I completely disassembled the parts from one with a bad shutter, and transplanted it into this one and voila! Sharp images at all focus distances.

Now that I had what I hoped would be a properly working Sensorex, I could evaluate it properly for the first time in over 3 years. Like all Miranda cameras, these were built to compete with professional grade cameras, and as such, they come with quite a bit of heft to them. Without a lens mounted, the body alone weighs 753 grams or about 1.7 lbs. Attach the monster 8-element 50/1.4 Auto Sensorex lens and the weight climbs to 1096 grams or nearly 2.5 lbs! This is a weight that you’d certainly notice dangling around your neck all day long, so care likely would need to be taken when carrying it for extended periods.

Build quality of the camera and lens is quite nice. Miranda developed a reputation as a lower quality camera, but it’s not outwardly obvious when holding one. The chrome plating and body covering is as good as the best out there, the motions of the wind lever, the shutter speed dial, and both the lens’s focus and aperture rings are nicely dampened with just enough resistance to feel purposeful without any wobble.

The top plate features from left to right, the rewind crank surrounded by a dual function dial for controlling the flash sync and the meter. You must remember to power off the meter after each use or else risk running the battery down. Immediately in front of this dial, on the front of the camera is a control dial for setting the maximum aperture of the lens attached to the camera. This is necessary to calibrate the meter to the chosen lens as Miranda didn’t incorporate an auto indexing feature until after this camera.

The middle shows the top of the rather large, but removable pentaprism. The Sensorex has a ground glass without interchangeable viewing screens, but can be used without a viewfinder attached, although a proper waist level finder helps block out excess light. To the right of the viewfinder is the automatic resetting exposure counter, film advance lever, and shutter speed dial with ASA film speed dial. The placement of the shutter speed dial is ideal as it not only helped to de-clutter the top plate, but allows it to be physically larger than other cameras, which makes it easier to use while wearing gloves or by those people with large hands.

The viewing screen of all Miranda SLRs is entirely contained within the body, which means you get the same exact view through the viewfinder, regardless of whether you’re using the pentaprism, a waist level finder, or if you’ve removed the viewfinder entirely. The focusing screen is not removable on the Sensorex, but is quite bright, especially considering the age. Brightness when using the f/1.4 lens wide open is even across the entire image. In the center is a ground class circle with a microprism dot in the center. On the far right of the image is the “hoop and stick” match needle, which on this camera wasn’t working.

The back of the camera features the battery compartment for the PX625 mercury cell. Of the 4 different Sensorexes I’ve had access to, only one had a meter that responded to light, but it was way off. Since mercury batteries are no longer easy to get and I didn’t feel like spending money on a Wein Air Cell, I tried a 1.5v alkaline battery, but like I said, it was way off. To the right of the battery compartment is a small release catch for removing the viewfinder. You must put tension on this catch while sliding the viewfinder back to remove it.

Opening the film compartment requires releasing a catch on the left side of the camera while simultaneously pushing in a button on the same catch. It’s a bit of an awkward motion and not entirely obvious the first time you handle the camera, but it does do a good job of keeping the door from being opened accidentally. Within the film compartment is an ordinary 35mm compartment. Film transport is from left to right onto a fixed and multi-slotted take up spool.

With the battery compartment and meter switch already accounted for, there’s not much else to see on the bottom of the camera other than the rewind release button and 1/4″ tripod socket.

All Miranda SLRs use a unique dual bayonet/44mm screw mount in which you press and hold two releases on the actual lens and twist to remove it. Although there were a few Miranda screw mount lenses made early on, they’re not common. The main reason for the presence of the internal screw mount is to use a large selection of lens adapters that Miranda made to allow you to adapt nearly any other SLR lens to their cameras. Miranda wanted their cameras to appeal to the professional photographer who might have been looking for a cheaper option, but they were wise to realize that once a photographer commits to a specific lens system, they are not likely to want to change. By offering the 44mm screw mount with a selection of adapters, it was thought that more people would give Miranda a try.

As for the bayonet mount, Miranda took an approach similar to Nippon Kogaku with their Nikon F-mount in that as the lens mounts got more advanced, they never changed the base mount, but would add additional couplings for features such as open aperture metering. The image to the right shows the external coupling arm where the lens and camera body connect. This coupling was only used on the Automex series and Sensorex and Sensorex II bodies. Mirandas from before the Automex in 1960 and starting with the Sensorex EE in 1971 either have no linkage, or an internal linkage.

If you have a Miranda lens that wasn’t designed for this external linkage, you can still mount the lens to the body, but if you want to use the meter, you’ll have to manually stop it down first.

Overall, the Miranda Sensorex is a finely designed and quality SLR that would have been very competitive upon it’s release in 1966. Of course that period of SLR design was rapidly changing, so it was only a matter of months before new designs by Canon, Yashica, Minolta, and several other companies had competing SLRs with the same, or better features available. Miranda felt the pressure at this time and due to what I can only assume was mismanagement and poor market performance, their sales and their quality control began to free fall after this model.

But now that I finally had one in good working condition, how did it perform?

My Results

With my absolutely horrid track record shooting Miranda cameras, I thought it best not to waste too much of my “good film” and for this roll, I tapped into a large supply of expired bulk Tri-X I picked up at an estate sale this past summer. The film came in a sealed container with an expiration date of 1994, and with Tri-X’s reputation as being a very hearty film, I felt pretty good the film was OK, but what would happen in the Miranda? Not wanting to take many chances, I shot it at box speed and hoped for the best.

If you’ve ever had the experience where you expected something bad to happen, but didn’t, and you were on pins and needles waiting for it to happen, but it never did, that’s what it was like shooting the Sensorex for the first time.

I have a such a fondness for Miranda cameras, yet time after time they have failed me. I am elated to say that it didn’t happen this time. The Sensorex performed flawlessly throughout this roll. Most of the images were shot with an Auto Miranda 28mm f/2.8 lens, but I also used the 8-element 50/1.4 for about a third of the roll. Perhaps as a credit to how well the wide angle Miranda lens performed, looking at the images in the gallery above, with the exception of the one of me in the mirror, I cannot tell which lens was used on each image. Both lenses performed really well. I’ve always had this belief that Miranda lenses were as good as others of the era, but getting through a whole roll without some kind of failure was so difficult, I never could make that determination.

So with a sense of immense relief, I can certainly tell you that in working condition, the Miranda Sensorex and it’s lenses were absolutely up to the challenge of competing with the best of what was available during the time they were sold. Sure, quality control might have been sub par, but I have to believe that at least some of my challenges are due to the perils of time. The Sensorex performed both in use and on film as good as I had hoped and while I know that my next adventure with one might not go as smoothly, I still greatly enjoyed the experience.

The heft of the camera inspires confidence and improves balance. The front shutter release button is perfectly located and feels natural to use. While I have no scientific evidence of this, I feel that for slower shutter speeds, the squeezing motion of your hand pressing into the body on the Miranda’s shutter release induces less motion than a typical top plate shutter release. The wind lever is perfectly located and easy to use with my right thumb. The viewfinder is large and bright and compares favorably to pretty much every other SLR of the day (with maybe the exception of the Topcon RE). Finally, that glass! I don’t know how many people are even aware that the Auto Miranda 50mm f/1.4 is an 8-element design, and although I do not own one yet, I plan on picking up a Miranda lens adapter to try these lenses out on my digital mirrorless camera.

In my time collecting, I know Miranda cameras already have their fans, and the Sensorex is one of those models that shows up in collections often, but I just don’t see many people using them. It’s likely because of the same issues with reliability that I’ve encountered, but based on this example, I encourage those of you with one in your collection, give it a try, and if yours doesn’t work, try to find another. It’s worth it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Miranda_Sensorex

https://www.35mmc.com/01/05/2018/5-frames-with-miranda-sensorex/

http://www.photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/index-frameset.html?MirandaSensorex.html~mainFrame

https://schneidan.com/2017/01/05/miranda-sensorex-big/

https://simonhawketts.co.uk/2014/11/08/miranda-sensorex-35mm-slr-camera/

Another truly excellent and well researched post. Loved it! Thanks! I have both a Sensorex and a Sensorex II sitting in a cabinet. One has a 50mm 1.4 and the other a 1.8. I have dry fired them and tested on different speeds. Both seem to do what you expect a camera to do. I need to test them soon. If nothing else, because they look so cool, especially the first one.. And the least I should do is get an adapter so I can try the lenses on my digital camera.

Wow that is a pretty detailed review and history with a persistence that is impressive, many would have given up at the first failure. Thanks for linking through to my small review, I’ve used mine a few times since and mostly happy with it’s performance and the resulting images. I actually have two of these the original version with the 1.9 lens and the slightly later 1.8 version.

The 1.8 is suffering from capping and so several shots have been missed due to that. I intend to get that camera serviced and the problem resolved (hopefully) at which point I will likely sell the other one which so far seems to work okay.

Glad you liked my review and saw my link to yours! Shutter capping was a problem on one of my first Sensorexes. I have a sample of it happening in my review of the Miranda D. I’ve had almost every problem imaginable with these cameras, including a very strange paper circle that one day just appeared inside of the focus screen. I had to open up the camera to get it out! I haven’t seen it in any other Miranda I own, so who knows where that came from!

Thanks, Mike for a fine, detailed review! I’ve had similar bad experiences with Miranda reliability and, since that was a known problem when these cameras were still available new in the market, I suspect that’s why none of the working pros I shot with ever used one. Their late 1960s – early 1970s bags were filled with Nikon F and F2, Nikon SP, Leica IIIG, Leica M2 & M3: All priced higher than Miranda but all remarkably reliable for day-to-day pounding. I have several Fs and F2s in the collection today and all are reliable (even the F2 meter can still be trusted). I used to collect Mirandas as well — enjoyed the heavy feel and the overall appearance just as you do — but I got tired of their erratic reliability, especially at today’s prices for film.

Mike, I’m trying to figure out which 50mm 1.4 you’ve got on the Sensorex in your article. Evidently, there were three versions? What is the filter screw thread diameter on yours? I think there was the 52mm and then the 46mm…

Bob, mine is the earlier 50/1.4 that would have come with the Sensorex-C. It has a 52mm filter mount.

I came to your site for the Bolsey B2 article — that was my first 35mm camera, a hand-me-down from my mother when I was 11. And saw in the picture of yourself on that page you were shooting a Miranda Sensorex, which was my first SLR and first camera I chose for myself. So then I had to come read what you had to say about the Miranda.

I bought mine in 1969, with the 50/1.4 lens, largely because it was the top-rated SLR in Consumer Reports. While it served me well, I did also learn from this experience that even the best consumer testing magazine wasn’t the best source of information about highly specialized products. I bought a (used) Leica M3, and swapped the Miranda system for an Asahi Pentax system (with a much bigger range of lenses than I had had) in 1973.

Thanks for the nice trip down memory lane!

David, I am happy to hear you enjoyed my reviews and you were able to reminisce through them. Do you still shoot any of those old cameras? As you already know and can see from my sample shots, these wonderful old things are still capable of some really nice photographs!

I picked up a Sensorex with its 50mm f1.4 and 35mm lenses and lens hood in mint condition at a local thrift store for $60. Popped a battery in and the light meter sprung to life. Checked the meter against my Pentax K-5 (50mm, f2.8 400 ISO 1/500) and the Sensorex is about 1 stop fast at 1/1000 using a 675 hearing aid battery.

I’m sure I paid too much for it after reading your review, but now I’m excited to load a roll and take a few shots!

Rob, to find a working Sensorex with the f/1.4 lens for only $60 is actually quite good. I’ve spent more than that on all of my Mirandas combined, before I finally found a good one. Optically, those lenses are as good as anything else made back then, and assuming everything goes well with yours, you’ll likely be very pleased with the results!

Miranda’s dual bayonet/threaded mounts result from the earliest Mirandas having only the threaded mount. When Miranda changed to the bayonet mount, the threaded mount was retained to avoid orphaning the lenses of existing users. While the threaded mount was used to later mount adapters for non-Miranda lenses to Miranda bodies, that function was incidental to the original purpose for the dual mount. I first acquired a Miranda only a year ago. After much looking, I acquired a Miranda adapter for the Tamron Adaptall-2 lenses, of which I have many I otherwise have used with my Nikon system over the years.

Hey Mike — I got a Sensorex C (as far as I can tell) with the 50mm f1.8 (and the flip-over leather cover) from the shopgoodwill.com site for $57 — looked good, but actual condition unknown. Cleaned it up, especially the battery compartment, and am using the Wein cell — and it seems to work great *except* the meter readings are funky compared to my middle-grade handheld meter. So I shot 1/2 of a roll of Kodak ColorPlus 200 36exp (cheap film, good for testing) using what my handheld meter told me, then the other half of the roll using the built-in meter. Hiked a few miles and hours with it — and yes, it definitely is a heavyweight! I sure hope that somehow the meter is working OK, or I can get it to work — since it is there, it would just seem right to use the internal meter. Any tips on why the meter would be “off”? And it doesn’t seem consistent. I’d say about 25% of the time the internal meter matched my handheld, but when it didn’t, sometimes it would be a teeny bit off (underexposing), and then sometimes drastically off (way underexposing)…. Oh well, such is the life of an old-camera-guy! Cheers!

Dana, there can be a number of reasons why the camera meter reading may be “off” when comparing its readings with those from a hand-held meter.

The first and obvious one will be the battery. As the meter requires a 1.35V battery, you will need a Wein cell, or a voltage reducing adapter for use with the Sensorex. Secondly, will be the effect of the subject field covered by the meters, and in the case of the Miranda, the metering pattern used. Invariably, this will mean that you will be metering different areas of the scene, unless purely by coincidence, both meters are reading exactly the same area, unlikely.

In the Sensorex, the metering pattern may be averaging, centre weighted, or centre/bottom weighted. I have no real idea which. Averaging metering gives too much predominance to the sky, and just as with the wide angle of view of selenium meters, the camera may need to be pointed more down to the ground to reduce the impact of a bright sky affecting, and thus, producing under-exposure. The metering pattern on your hand-held meter will be average weighting, even if you have a model with selective viewing angles. All these latter permit is a more accurate sighting of a smaller area of the subject. The centre weighted reading is useful for measuring what the camera is being pointed, but averages the top and bottom parts of the scene for the final recommended exposure. Centre/bottom weighted mainly ignores the sky for a generally quite balanced exposure.

TTL metering, as it restricts the angle to be metered to the light actually passing through the lens, is not matched by many hand held meters most of which will have a wider field of view for metering. So light sources not “seen” by the camera will affect the reading of a hand-held meter. Thus the balance of light and dark that the two meters actually read can be different.

Cds meters usually have a much narrower angle of view than selenium meters, so even with hand-held meters of these types exposure readings needn’t agree. I’d suggest the best way to check meter readings is to fill the frame with an 18 degree grey scale, which is how meters would have been originally calibrated. Do this with the camera and your hand-held meter and see what the difference is. If there is a difference and you prefer the results from your hand-held meter, compensate accordingly by adjusting the film speed setting.

If I understand correctly, this Miranda exposure meter weights the bottom half of the picture in order to pick up details of (terrestrial) subjects in a bright sky environments. Your exposure meter most likely does not do this.

Hi Mike!

‘Nother excellent piece. I very much like the Tri-X shots – it’s so hard to “just go out and shoot” to test gear and come back with shots worth exhibiting but you’ve managed to do just that.

And the look of these is really beautiful. ISO? Developer? Are they slightly toned?

Bob Palmieri

Thanks for the complements Bob! As you likely read, this Sensorex was a pretty big victory to me as I had attempted to shoot several other Sensorexes over the years and continually ran into problems, so when I managed to successfully get through this roll and get nice images, I was elated. The film was Kodak Tri-X 400, expired in the mid 1990s that I picked up at an estate sale. I shot it at box speed and developed it using HC-110 Dilution B. The images were scanned on an Epson V550 in 16-bit black and white, so no toning was done. In some cases, I will edit the images using Photoshop CC to remove hairs and other dust particles if they negatively affect the image, and on occasion, I’ll even crop an image for greater compositional effect, but otherwise no other digital manipulation is done to these images.

amazing to read the review.. I still have mine from the 60s although must admit it is a few years since it had film in…

I found it reliable and great quality pictures when i was processing my own black and white ..

Lovely article about camera’s made with love. Maybe there was another but I am sure Soligor made the optics for Miranda.

In one advert the lenses are called ”Miranda-Soligor” and the ”Miranda G” was also sold under the Soligor name (as wel as ”Pallas”).

I owned one from 1967 until the early 1970’s when it was stolen while I was at university. I had the 1.4 lens and a Lentar 300mm screw mount (that I still own and have used on Nikon, Canon and Konica bodies). It was one of the best cameras I have owned.

I have a Miranda Automex II still in its original box and waiting in line to have a film put through it. It is in as new condition so I will read your review with interest.

Hi! Do you know if the Miranda EC lenses are also compatible with the Sensorex? I know they are bayonet mount but they have an extra internal pin for meter. Thank you!

Yes, the Miranda EC lenses will physically fit onto a Sensorex and allow you to take photos, however the EC lenses lack the external coupling arm that allows the meter on the Sensorex to know which aperture you’re at, so if you wanted to use the meter on your camera, you could only do it with the lens manually stopped down, or you would just not use the meter, and shoot manually. To be honest, shooting manually is your best bet as its unlikely the meter on your Sensorex is working and accurate anymore.