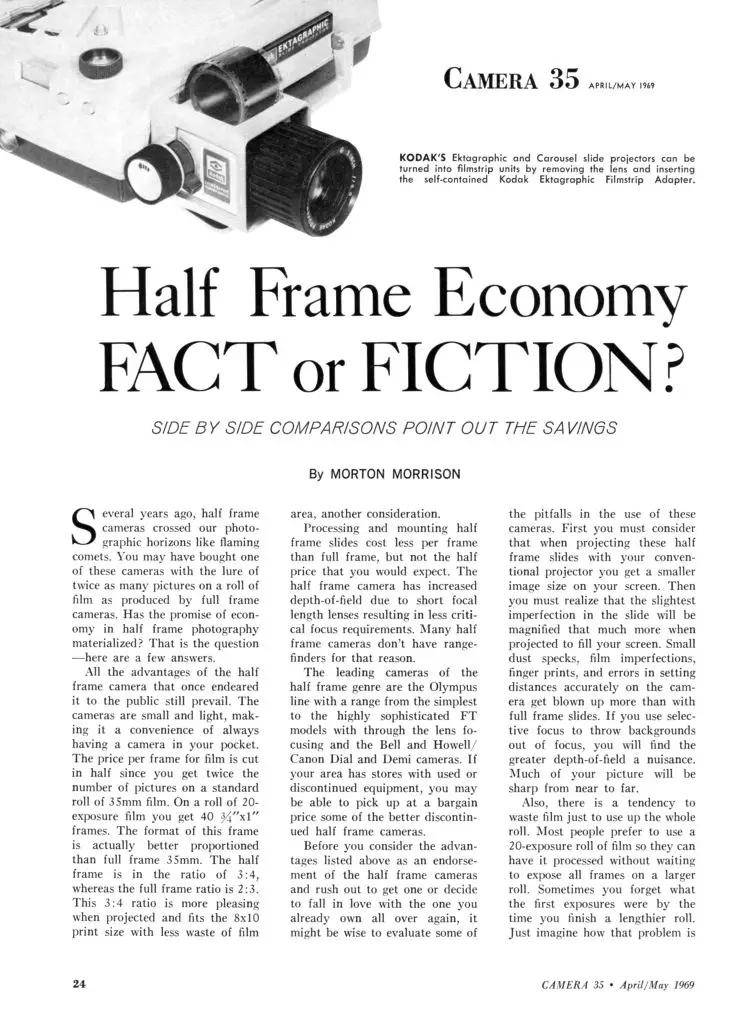

Following up on my post earlier this week for the Yashica Samurai X3.0 35mm half frame camera, I thought it would be interesting to take a look at an article from the April/May 1969 issue of Camera 35 magazine that explores the myth of half frame economy.

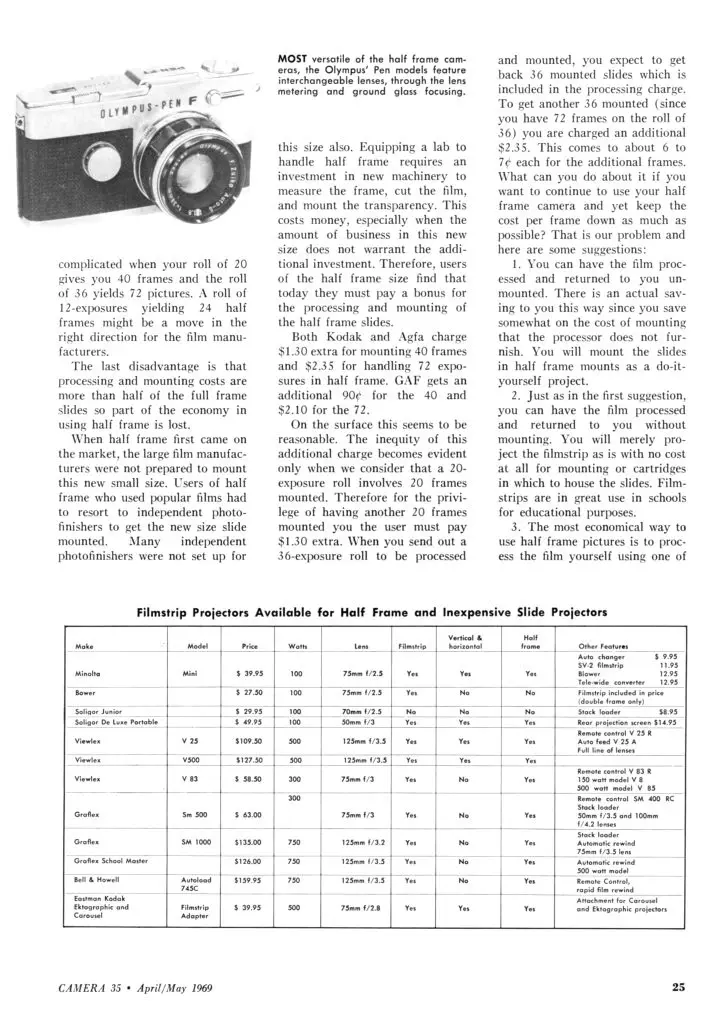

Excluding half frame 35mm cameras from before WWII like the Universal Mercury CC or ANSCO Memo, the majority of half frame cameras produced after the war came out of Japan. Starting with the Olympus Pen in 1959, the economy of getting twice as many images per roll of film on a small and compact camera was immensely appealing to Japanese photographers.

Although many of these models were sold in the United States, the format wasn’t nearly as successful here as it was overseas. Of the available half fame models, they almost universally sold poorly, and some models weren’t even offered for sale here.

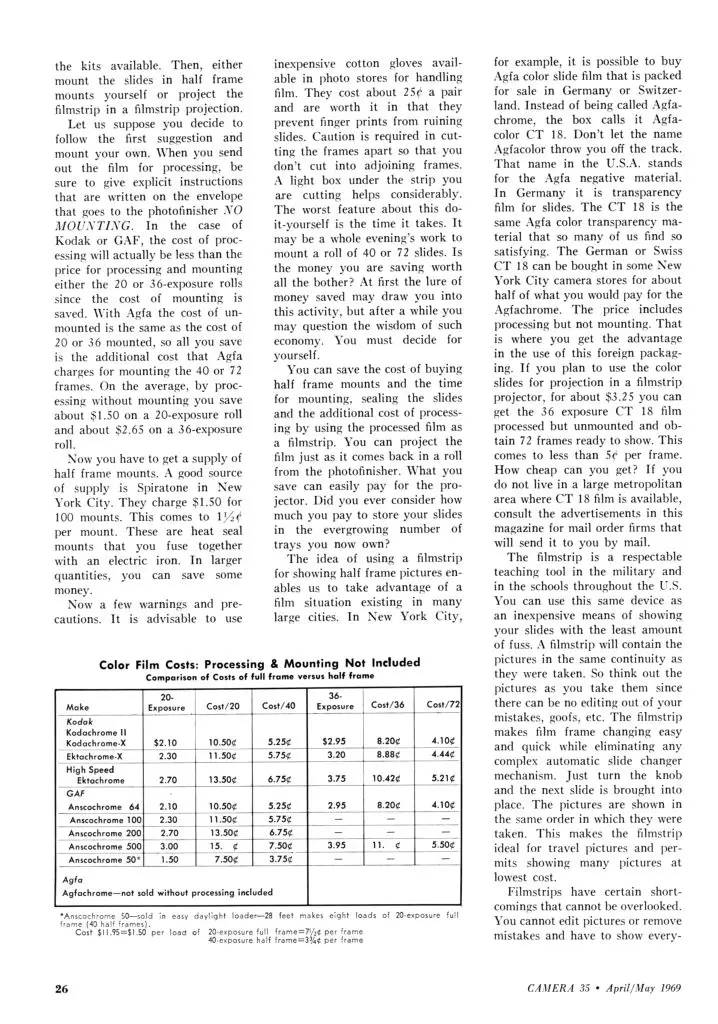

But why? If a 20 exposure roll of Kodachrome cost $2.15, but you could get 40 exposures for the same amount of money, shouldn’t that savings appeal to Americans just as much as the Japanese?

As anyone whose ever shot film before knows, the expense of film does not end after purchasing the film. You still need to develop the film, and in the case of slide film which was the dominant type of film for the 1960s American family, there was yet another cost in mounting the slides. The article below spends nearly it’s entire time talking about the additional expenses and difficulties in mounting half frame slides, yet strangely does not mention color or black and white negative film at all.

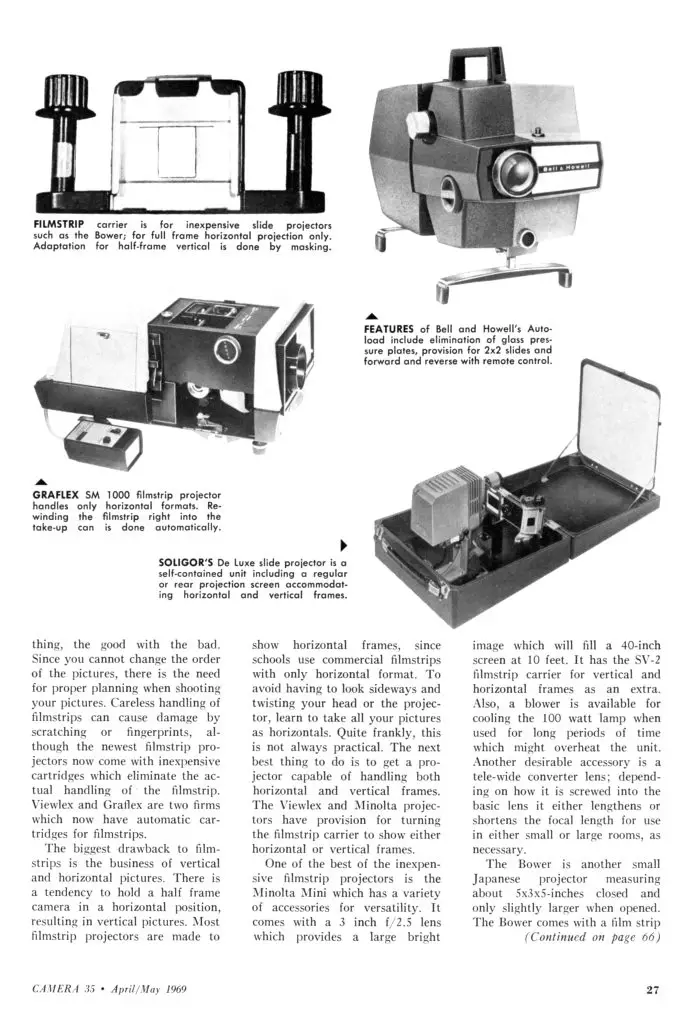

The article also covers some difficulties with half frame slide film such as having to account for the increase in 90 degree rotated images due to the natural portrait orientation of most half frame cameras back then, along with the need to use slide projectors that were half frame compatible.

Despite the overall negative attitude in this article towards the supposed “economy” of half frame, it attempts to offer ideas to help offset the costs by suggesting mounting your own slides, home development kits, and bulk loading your own film, something that the average family photographer likely wouldn’t have had an interest in doing back then.

By the time the Yashica Samurai made it’s US debut in 1988, slide film was no longer the preferred type of color film for the American family photographer, as negative print film was much more common. While printing a half frame image still had it’s challenges, it wasn’t nearly as complex since specialized mounts and projectors weren’t necessary.

So, if the next time you’re browsing through eBay looking for an inexpensive half frame camera, and wonder why so few of them are available by US sellers, this article should help paint at least a partial picture of why.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2019.

I understand that for the Japanese after WWII photography was very expensive. This explains the plethora of 16mm sub-miniature cameras on the market. Most used normal 16mm film in little cassettes from the likes of Mamiya and Minolta, for example, while others used film with backing paper. Preceding half-frame, there was a following for sub-miniature photography in the 1950’s and 1960’s and which subsequently saw the likes of Rollei and Edixa get in on the act. In fact the Rollei 16 and 16S were, and still are, quite sophisticated system cameras. The problem was the film available at the time which severely limited image quality. In reality 16mm cameras would morph into 110. Hence the same negative size.

Then along came half-frame, and which to be quite harsh on it, didn’t materially change things, although at around 24x18mm it didn’t give much of an improvement, when enlarged, over sub-min negs which were usually around 17x14mm. Despite the popularity of colour negative film, the general quality of it left much to be desired.

In passing, I’m not sure that the image of the Minolta projector above was with half-frame in mind. Unless there is evidence to the contrary, I believe it was released for showing mounted Minolta 16mm sub-miniature slides which were mounted in standard 2×2 inch mounts, as were half-frame slides.

Terry, thanks for the detailed historical context into “smaller” formats in Japan!

In regards to the Minolta projector I include an image of, I went off the chart that appears on the second page of the original article which claims that model support both half-frame slides, and a filmstrip mode. I have no personal experience with it however, so if you think it’s incorrect, the blame goes to Morton Morrison! 🙂

Mike, I’m wrong on this one. The only mini Minolta projector I was aware of was the one intended for sub-miniature projection. But l’ve taken a closer look at the image above and seeing what looked like “35” I checked on the well known auction site and, indeed, Minolta made small projectors for 35mm that followed the design of their sub-min one. It was the design concept that fooled me.

Folks, there were several “pocket-size” slide projectors dating to the 1960s and ’70s that accepted 2×2 mounts. I’ve had a few; the one I kept is branded “TMC” and has a “Rohar” 75mm f2.5 lens, a simple push-pull carrier for two slides, and a 100 watt bulb which is cooled by convection. The beauty of these projectors is their size: About 6″ long by 3″ wide by 4″ tall when closed. Easy to carry in a briefacse or overnighter, which makes up for the sorta-dim screen images they throw!