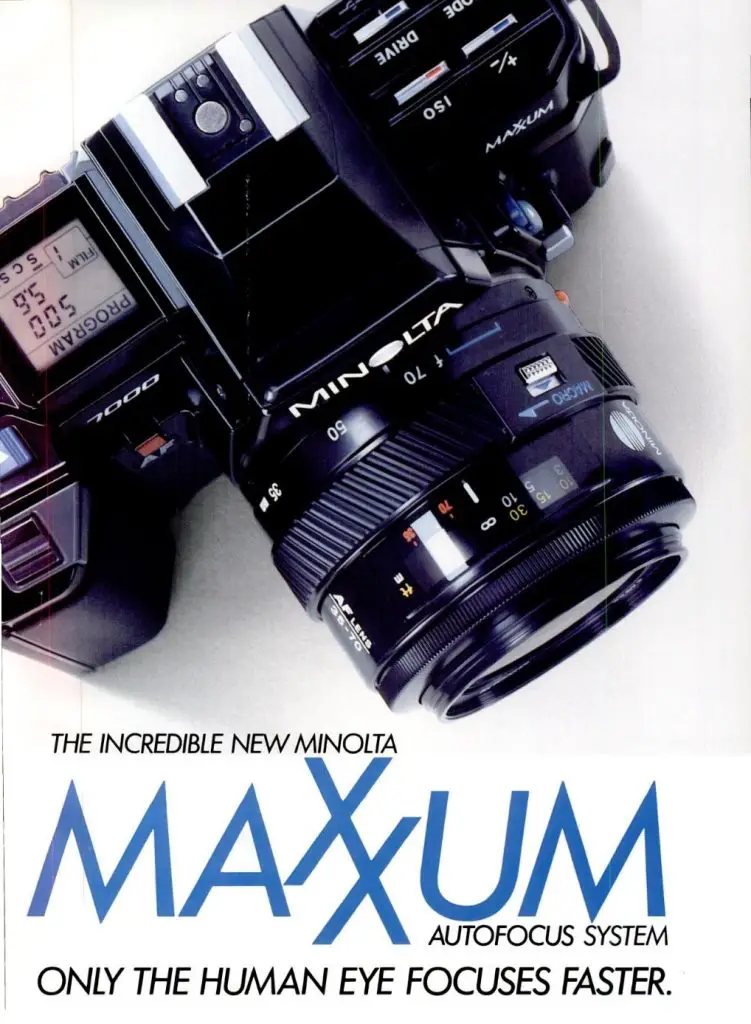

This is a Minolta Maxxum 7000, a 35mm SLR made by Minolta Camera Corp in Japan between the years 1985 and 1988. This version of the camera was sold for export in North America, and when sold in Europe and Japan was known as the 7000 AF and α-7000, respectively. Whichever name it had, this model is historically significant as it was the first mass produced 35mm SLR camera with in body auto focus. It beat it’s rivals in Japan and Germany to the market with a usable AF body in some cases by more than a year. The Maxxum 7000 also introduced a new lens mount, the Alpha Bayonet mount, which replaced the earlier Minolta SR/MC/MD mount used in manual focus cameras.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.7 Minolta Maxxum AF coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Minolta “A-type” Alpha Bayonet

Focus: 18 inches to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism w/ LCD Readout

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Metal Blade

Speeds (manual): B, 30 – 1/2000 seconds

Speeds (auto): 1 – 1/2000 seconds, stepless

Exposure Meter: Full Program PASM Automatic Exposure

Battery: 4x AAA battery or 4x AA battery w/ optional BH-70L holder

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe with TTL Flash Metering and 1/100 Sync

Weight: 834 grams (w/ lens), 651 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_maxxum_7000.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Minolta Maxxum 7000 is a historically significant camera that not only ushered in a new age of auto focus SLRs, but it also set the bar quite high for what a modern SLR should be like. The camera was designed well, with good ergonomics, an excellent viewfinder, and an auto focus lens system that was very accurate and much better than many earlier implementations of the technology. The Maxxum 7000s lens mount is still used today by Sony, and it’s lenses are not only very well made, but can easily be adapted to modern cameras today. This is a rare example of a camera with a lot of history that is still quite usable today. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.0 | ||||||

History

Minolta released the Maxxum 7000 in February 1985 as the first interchangeable lens SLR camera with in-body automatic focus, a concept that even 10 years earlier, would have sounded like a fantasy. The idea that a camera could automatically determine the proper focus for an object seen in the viewfinder and instantly adjust for that was revolutionary.

Although a pioneering camera, the Maxxum 7000 wasn’t the first camera with auto focus. In November 1981, Asahi Pentax would release the Pentax ME F, a heavily modified version of the ME Super which used an in body electronic contrast detection system that when coupled with specialized auto focus lenses with externally mounted motorized drives, achieved the first 35mm SLR with auto focus. Other manufacturers like Nikon and Canon would also have their versions of externally mounted auto focus systems as well.

For the first auto focus SLR of any film format, there is the Polaroid SX-70 Sonar from 1978, a folding instant camera with an externally mounted auto focus sensor that used sonar to detect distances from an object. Although an inefficient method for focus detection, it had the benefit of working in total darkness, something that even the most modern systems can struggle with. The camera looked just like a regular SX-70, but with a large black sensor mounted to the top.

In November 1977 the Konica C35 AF became the first mass produced point and shoot camera to feature a passive auto focus system. It utilized a rudimentary method created by Honeywell called the Visitronic system that used an optical rangefinder and a variety of sensors to determine the correct focus distance of an object.

Prior to the appearance of auto focus in consumer still cameras, experimental auto focus systems were shown at various trade shows and in some instances incorporated into lens collimation devices and early television cameras. If you look up on the Internet the history of auto focus, you will keep hearing the name Leitz mentioned, as Ernst Leitz of Wetzlar had been playing with the idea of an automatic rangefinder as far back as 1960.

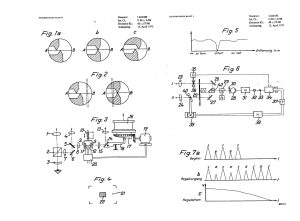

In my research for this article, I found patent number 1423655 filed by Ernst Leitz Wetzlar on October 21, 1960 for a “Verfahren und Vorrichtung zur Entfernungsmessung” or “method and device for distance measurement” in English. I do not read German, so I couldn’t understand the text of the patent, but this drawing at the end clearly shows some type of contrast detection system which detects a high voltage or current at both “zu fern” (too far) and “zu nah” (too close), and then a drop at “scharf” (sharp) when they overlap.

At Photokina in September 1976, Leitz famously debuted their new “Correphot” auto focus SLR, a heavily modified Leica R4 with an in body auto focus system. Leitz’s system used twin CdS exposure meters that through some electronic voodoo, could detect the sharpest moments of contrast and compare them between both sensors to achieve a sharply focused image. The auto focus system was contained within the body but still required the user to manually focus the lens, or with an optional attachment and specialized lenses, true automatic focus could be achieved. Although it was said that Leitz’s system worked, they abandoned the technology shortly after it’s announcement, selling it to Minolta, as they didn’t think the typical Leica user would ever need it.

Most internet articles about the history of auto focus stop there, crediting Leitz as being the first to create a system, but the story is much more complicated than that as I’ve found a large number of prototype systems that predate the Correphot.

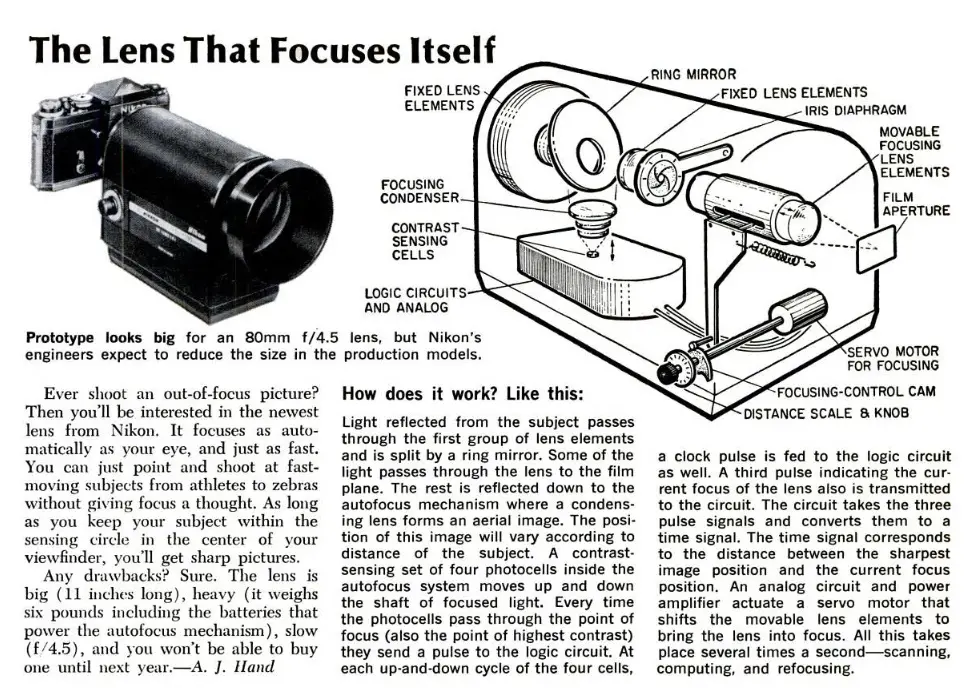

One of those prototypes was a 6 pound monster 80mm f/4.5 lens developed by Nippon Kogaku for the Nikon F. Said to have been in development since 1965, the “Lens that Focuses Itself” made it’s world debut at a Chicago Photo Expo in April 1971. I don’t believe any were ever sold to the public, but at least one of them is out there, somewhere.

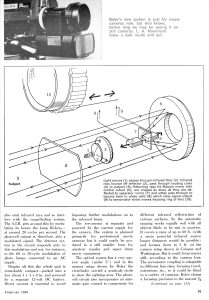

At Photokina 1968, Bolex demonstrated a revolutionary A.I.R. (Automatic Infrared Rangefinder) system for motion picture cameras. Using a combination of pulses of infra red beams of light and CdS meters which detected the amount of light bounced back, the system could accurately calculate the distance of an object and set the correct focus distance. Perhaps even more amazing is that the system did not require special lenses, and could control a variety of manual focus lenses mounted to the camera. In the image to the right, the A.I.R. system is mounted to an Angenieux 12-200mm zoom lens, controlling it with servo motors.

The February 1969 issue of Modern Photography ran a short article on the system with more details about how it worked. You can review this article in the gallery below.

Even before Bolex and Nikon got into the AF game, in June 1963 at Photokina, Canon revealed a new auto focusing rangefinder camera, simply called the “Canon Autofocus”.

The camera was a strange looking twin lens rangefinder that had a normal 40mm f/2.8 lens surrounded by a selenium cell exposure meter, but on the other side was a 75mm f/2 mirror lens that sent a magnified image through a beam splitter to the center of the main viewfinder window like a traditional coincident image rangefinder. The camera’s automatic motors and various electronic gizmos automatically swept through the full focus range, analyzing the light coming through the rangefinder, and when the two images lined up, a sensor would detect a brief moment of increased contrast (since the images are overlapping each other like in a normal rangefinder), and triggered an electronic circuit that fired the shutter. It is said this whole sequence took less than a second and supposedly was quite accurate. The camera was merely a prototype though and never went into production, so there has never been anyone who could confirm it’s functionality.

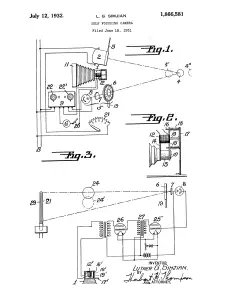

Going back even farther than 1963, various patents and other miscellaneous ideas were thrown around by a large number of companies like Voigtländer, Kodak, and others for how to automatically focus a lens. The oldest on record is US Patent 1,866,581, submitted on June 6, 1931 by an Armenian inventor named Luther George Simjian.

Simjian’s “Self Focusing Camera” was never built and only existed in patent paperwork, but pioneered the idea of using a type of photoelectric cell to determine maximum areas of contrast when an image was in focus. Whether the technology existed in 1931 to build such a device is anyone’s guess, but at the very least, it suggests that people were thinking about it, and the continued use of light sensing devices proves that Simjian was on the right track.

Despite there being many iterations of auto focus prior to the release of the Minolta Maxxum 7000 in 1985, it was still pretty big news. There had never been a serious camera available by any company that had the feature built in, without relying on specialized lenses with bulky auxiliary motors.

Minolta’s Executive Director of Research and Development, Ichiro Yoshiama knew that if they were going to convince the photo shooting public of the need to have SLRs with auto focus, they couldn’t just release a single model with a single lens that supported the feature. They knew that the camera had to look and work like SLRs that came before it, and that the lenses couldn’t be bulky or excessive expensive.

One of the most important decisions Minolta made for the new camera and lens system was to abandon it’s manual focus SR/MC/MD mount which dated back to Minolta’s first SLR, the SR-2 from 1958 and come up with an all new mount. Originally called the Minolta A (or alpha) mount, it would still be a bayonet type but would be slightly larger in diameter and allow for full control of the lens through electrical connections on the flange. Another major change, and one that nearly every other SLR maker would eventually embrace, was putting the electric auto focus motor within the camera itself, and using a physical screw coupling between the body and lens. This meant that the size and cost of the new auto focus lenses could be kept to a minimum, and by having the motor within the camera, it could be further dampened to minimize noise.

The new lens mount meant new lenses, and what good is a new lens mount if there’s not a good selection upon it’s release? Well, Minolta thought of that and had as many as 12 different lenses ready, including 5 zoom lenses, and primes from 24mm to 300mm at launch. The Minolta 7000 would hold the title of Minolta’s only auto focus SLR only for a very short time, as the company had two other models ready, called the Maxxum 5000 and Maxxum 9000. Interestingly, the 9000 was completed before the 7000 was ready for release, but the company didn’t want auto focus to make it’s debut with a professional level, top of the line camera, for fear that it’s price would turn people away. The Maxxum 9000 would make it’s debut in August of 1985, and the 5000 a few months after that, in early 1986.

Being first to the market with a new technology that many photographers didn’t think they needed, using a new lens mount that was incompatible with every Minolta lens made for the previous 25 years, after investing lots of time and energy into creating 12 new lenses and 3 new cameras was a huge risk for Minolta, a company which by the mid 80s was slowly falling behind other Japanese companies like Nikon and Canon. Thankfully, their gamble paid off and the Maxxum 7000 was a big success and was positively received by the press and photographers alike.

Fun Fact: When it was first released, the Maxxum 7000 had a stylized logo where the two X’s crisscrossed over one another. This upset the Exxon Corporation who had a similar design to their logo and took Minolta to court, requiring them to change the logo. A small number of Maxxum 7000s are out there with this earlier logo and are more sought after by collectors.

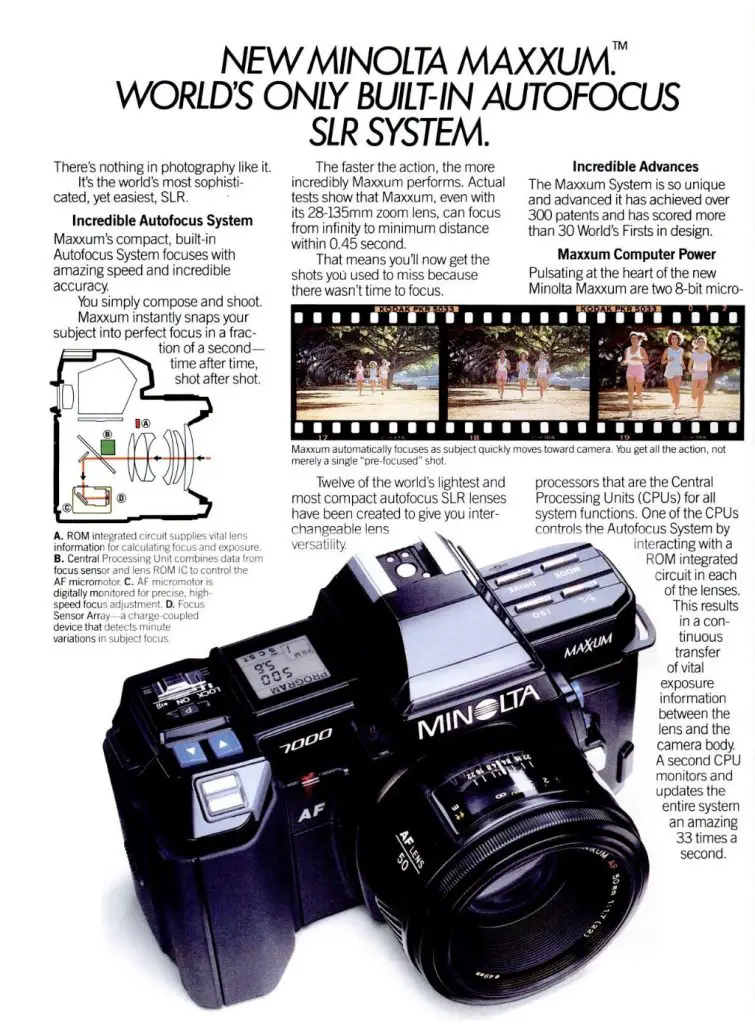

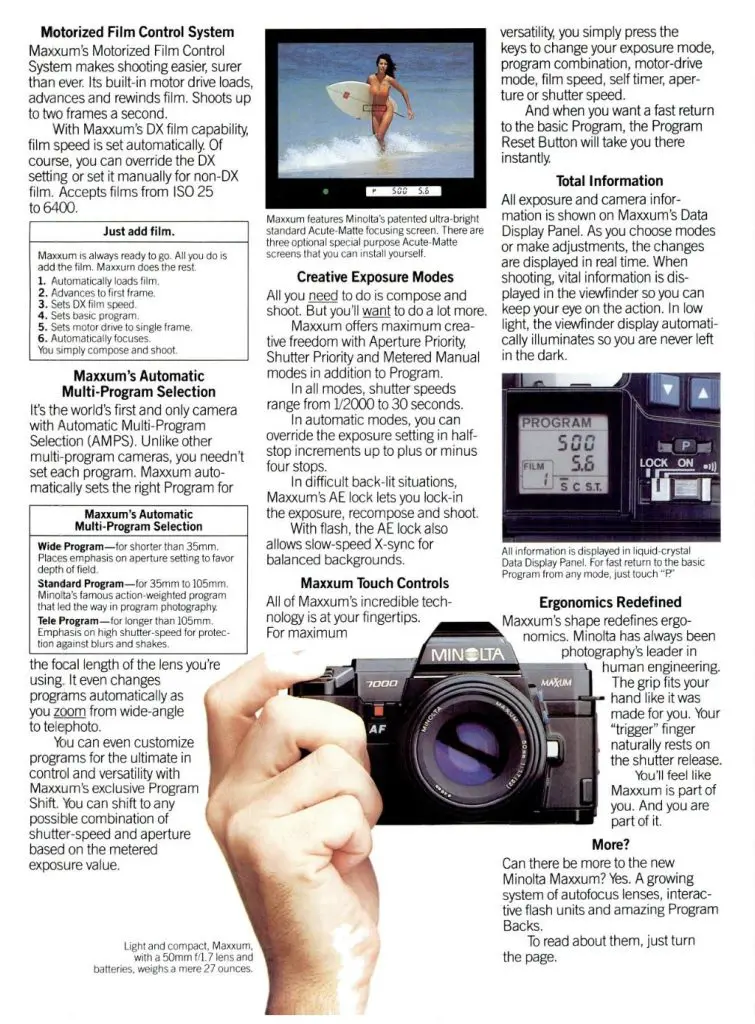

The following 12 page article comes from the March 1985 issue of Popular Photography and thoroughly examines the camera, it’s new lenses, and the technology behind the focusing system. It’s a long read, and probably more in depth than the average person likely needed to know, but this was a changing point for the entire industry, and Pop Photo thought it was important to document all of the information that they could find about this new model. As with all scanned articles I provide, there is a link in the gallery for each page which allows you to view it full size on your display for easy reading.

Upon it’s release, the Maxxum 7000 was every bit as good as it’s technology promised. Minolta chose wisely to release the mid-level 7000 first, as the professional Maxxum 9000 would have been way out of the price range of the customers most likely to want auto focus, and the entry level 5000 wouldn’t have had the additional features that proved to the pros that auto focus was a worthwhile feature to have.

Edit 8/7/2020: After posting this article I found another in depth review of the Maxxum 7000 from the August 1985 issue of Modern Photography.

Edit 2/5/2021: Here is yet another new article I found, this time from the February 1986 issue of Popular Photography.

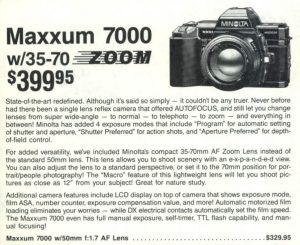

The Maxxum 7000 sold with a 50mm f/1.7 AF lens for $329.95 or with a 35-70mm AF Zoom lens for $399.95, which when adjusted for inflation, is comparable to $765 and $925 today which puts them into the same “advanced amateur” market as cameras like the Sony alpha-7 mirrorless.

I never could find any production numbers for the Maxxum 7000, but based on how often they come up for sale, I have to assume that quite a few were made. That means today, they’re not exactly hot items for collectors, but their place as a historically significant camera means they deserve at least some notice.

A combination of modern features, with a lens system that is still usable today for Sony digital users, and pretty good performance (at least compared to other 1980s SLRs), the Maxxum is still a compelling option for people wanting to get into film photography. Sure, there were many other auto focus SLRs made in the 1980s, but this camera’s history makes it worth a look, especially at the rock bottom prices they typically go for today.

My Thoughts

Without any historical context, unless you were an active photographer in the mid 1980s when this camera made it’s debut, the Minolta Maxxum 7000 looks like any other run of the mill plastic SLR from the 1980s. It’s got a lot of buttons, a sharp angled design, and a lack of mechanical controls like a film advance lever or shutter speed dial. I have several cameras like this in my collection, the Nikon N2020, a couple Canon EOSes, and a Pentax or two and they all work about the same. By the time these models had come out, little of the classic design that I love from previous generations remained, and the cameras themselves turned into sterile, predictably decent SLRs that would consistently give you good images, but without any of the fun or quirks or older models. Knowing the history behind the Maxxum 7000, the first 35mm SLR to offer in-body, fully automatic focus with an all new lens mount, I thought it was worth a closer look.

Since the experience of using the Maxxum 7000 is all in it’s auto focus performance, I won’t spend as much time as I usually do going over the various controls of the camera. The 7000 was designed to be used by novices and advanced amateurs alike. It offers nearly every shooting mode you could possibly want, including full Program auto exposure. If you prefer Shutter Priority, Aperture Priority, or complete manual control, those options are available to you as well.

The top plate has several labeled buttons, a sliding power switch, two up/down mode selector buttons, the shutter release and a nice LCD screen for displaying all relevant information about the camera and it’s operation.

Loading film into the Maxxum 7000 is fully automatic. Simply insert a new cassette and extend the leader out to the red mark next to the take up spool, close the door, and the camera will do the rest. The camera supports full DX detection and can automatically set film speeds from ISO 25 all the way to 6400 with manual override if you wish. At the end of a roll of film, the camera will stop trying to advance the film, but requires that you manually activate the rewinding mode. Although this can be triggered before the end of a roll of film, the manual doesn’t mention any method for leaving the film leader out of the cassette for finishing in another camera mid roll.

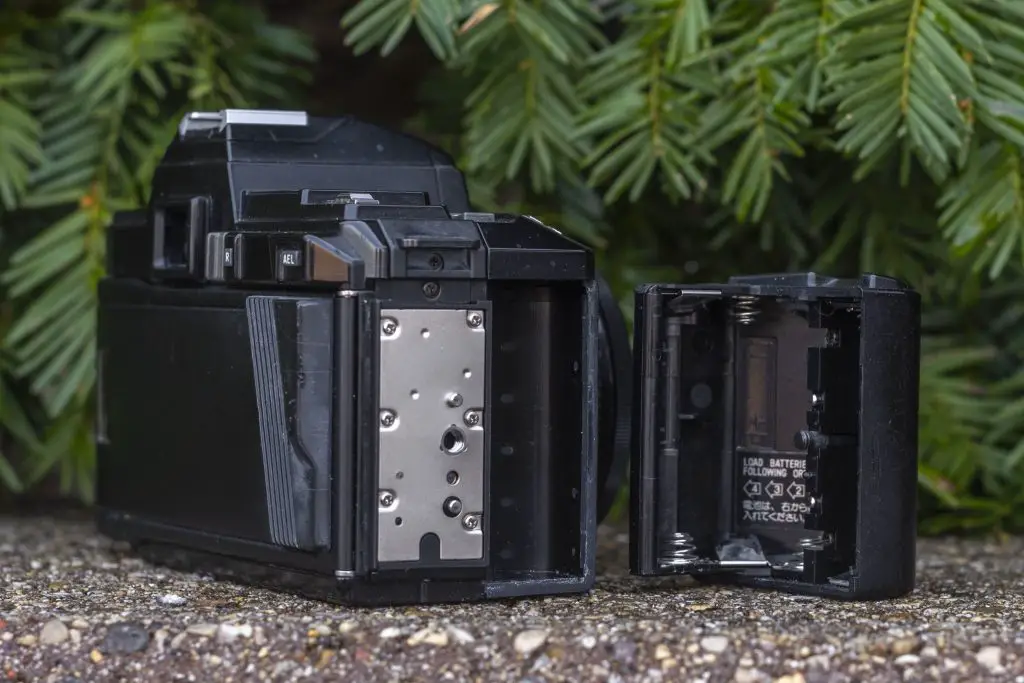

The film door on the Maxxum 7000 is removable by sliding a small pin in the hinge. This allowed for installation of one of two Programmed data backs that were available at the time.

For power, the camera normally uses four AAA batteries for power. There was an optional BH-70L battery holder which used AA batteries for more overall life between changes. Whether you use the AAA or AA holder, the entire compartment comes off the camera for ease of loading. With fresh batteries, the entire holder clips back into the side of the camera, and also doubles as a hand grip.

The shutter in the Maxxum 7000 is a electronically controlled vertically traveling design with a range of speeds from 30 seconds, all the way to 1/2000, keeping it on par with offerings from other mid level SLRs of the day. The vertically traveling design allowed for a flash sync speed of 1/100. Manually setting the shutter speed to anything higher would override it back to 1/100 to prevent incorrectly exposed images. The camera has no built in flash, so you must attach one of three available Minolta flashes for correct TTL flash metering. A standard hot shoe flash can also be used, but without TTL metering.

The Maxxum 7000 has a very modern viewfinder with all of the advancements you would see on an advanced SLR today including a bright focusing screen and a full information viewfinder with 8-segment LCD display. Not typical of the price point however, is that the focusing screen was interchangeable with 3 different screens that were made for it. The default “Type G” screen did not have any manual focus aides and simply had an auto focus indicator in the center, but a traditional split image with microprism collar screen “Type PM” was also available, along with two others.

Like all technologies, auto focus took a while to perfect. Using an early auto focus camera really makes you appreciate the advanced focus systems available in today’s cameras. Earlier models often struggle in a variety of circumstances, including objects with fast motion, low light, shooting through glass, or objects with low contrast or even lots of vertical lines. Even when these early systems get the focus correct, they’re almost always slow, and while the Maxxum 7000’s system certainly isn’t perfect, it was pretty good, and worthy of a look today.

My Results

My first use of the Minolta Maxxum 7000 came rather unexpectedly when I attended a friend’s funeral. I had another camera with me that I had intended on shooting that day, but I hadn’t realized that there was only one exposure left on the roll. After making that last exposure, I found myself without anything to shoot, so I looked in my bag and pulled out the Maxxum (doesn’t everyone carry around bags with random cameras in it?)

Knowing that the real test of this camera would be in it’s auto focus performance, I figured I would stick with Fuji 200 as I do with most test rolls, as it’s a predictable and easy to shoot film.

With this first roll, my thoughts on the Maxxum 7000 are less about the quality of the images it made, but more about the auto focus system and the experience in using it. What impressed me the most was how good Minolta got it on the first try. I’ve used a number of early auto focus point and shoots like the Canon AF35M, Ricoh FF-90 Super, and Pentax PC35AF, and I’ve always tried some early auto focus SLRs like the Nikon N2020 and the Canon T80 and they all have three things in common, they’re loud, they’re noisy, and they don’t always get it right. While the Maxxum 7000 also exhibits each of those characteristics, it’s just a little better than the rest.

The AF isn’t as fast as a modern DSLR or mirrorless camera and certainly makes more noise, but is it really fair to compare the first example of a technology to a model that was made decades later? In terms of accuracy, the Maxxum handled static shots with a clear focus point very well, but when I tried to trick it with angled closeup shots (such as the red flower on the wall) or a moving child, it got it right every time. Sure, there was a bit of hunting, but nothing I would deem excessive. I have to think that anyone picking up this camera for the first time in 1985 would have been very impressed with how good the technology worked. Despite my favorable review of the Nikon N2020, the Maxxum 7000’s auto focus system blows the Nikon out of the water, and no point and shoot I’ve handled made before the early 90s even comes close.

Nikon has famously stuck with the same F-mount that made it’s debut on the original Nikon F in 1959, and while some people love that Nikon has never forced photographers to completely start over with a new mount like Pentax, Minolta, and (later) Canon did, the Nikon F-mount is not immune to compatibility problems. Just check out Ken Rockwell’s Nikon Lens Technology page and the number of acronyms and “if this then that” combinations is mind numbing.

So, while starting over from scratch with a new lens mount for an established company does have some drawbacks, Minolta chose an ideal time to do it, and both the design and their preparedness for it was very well handled. The new Maxxum mount is still in use today in Sony DSLR cameras as the alpha mount and is compatible with the earliest Maxxum lenses from 1985.

If you’re looking to get back into film, and want an easy to use fully featured SLR with the modern conveniences of automatic everything, is the Maxxum a good option? Not necessarily. This is still a primitive electronic SLR. It’s auto focus system is limited to only a single focus point in the center of the image. Phase detection is easily tricked by moving objects, or in low light. The auto exposure system only supports center weighted average light through a single SPD cell in the viewfinder. The camera is bulky and relies on AAA (or AA with an optional grip) batteries with generally poor life.

On the other hand, it is capable of capturing the same types of images that a later, and more advanced model could. The Maxxum 7000 does everything it should, just a little slower. I really enjoyed my time with this camera, and for the prices these things go for (I sometimes see them sold in lots of multiple bodies for just a couple of bucks), they’re worth checking out. From a budget perspective, you’ll spend far more money on the lenses, because they’re still useful to Sony DSLR users today, but I can’t hold that against the camera.

I think the overall conclusion I drew from this camera, is that Minolta took a big risk with this model. They changed mounts, and invested heavily in an unproven technology, and they pulled it off. Based on my experience with other cameras of the era, the Maxxum is a home run. It never missed a shot, and while I wouldn’t recommend depending on one for any type of professional work, it is a historically significant camera, and better yet, it still works.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_7000

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/maxxum7k/index.htm

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2018/09/12/ccr-review-97-minolta-maxxum-7000

https://www.kenrockwell.com/minolta/maxxum/7000.htm

https://cameralegend.com/tag/minolta-maxxum-7000-review/

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a3f7/48bb4eebccd5d5d0ab587362621f9c8bc87c.pdf (this is a really great article about the history of auto focus)

Another great read Mike. Yashica in the late 70s had begged Zeiss to allow them to develop an auto-focus camera and lenses, but Zeiss refused; which is how the Contax AX was developed. The Pentax ME-F was the very first TTL autofocus SLR to reach the market in 1981, but the Minolta was the first “Successful” autofocus lens.

https://camerapedia.fandom.com/wiki/Pentax_ME-F

The Nikon F3 AF was also released in 1983, and Chinon produced the first commercially available Auto-Focus lens. So first prize actually goes to the Pentax, with the Minolta coming second by a nose.

This is great info Cheyenne. I was away of the Nikon F3 and I actually have a Canon T80 in the queue to be reviewed sooner, but I figured I would just make a passing reference to them. Whenever that T80 review is done, and if I ever get my hands on a Nikon F3, I’ll likely go back and update this to include mentions to those articles. That Chinon lens looks very interesting!

Yup, the Maxxum 7000 remains a capable and eminently usable camera. If, that is, you can find one still working. I’ve owned two and both had a common fault, a failed aperture-control magnet. This condition leaves the aperture at its smallest setting at all times. f/22 anyone?

It seems electronics and Minoltas aren’t mutually compatible as I know the X570 and X700 cameras often suffered from ailments like this too. Thankfully, my Maxxum 7000 had no such issues and continues to work correctly.

Hi Mike, your review is incredible! This is the best review I have seen on the Maxxum 7000 in years, probably best ever! No joke, you really put so much into this and I appreciate all the details, fascinating reading! Thanks for including my article in your links, but I humbly say your review here is so much better and I’ve included it in my Maxxum 7000 resources as well. By the way, I’ve been enjoying your reviews for years, sorry I never left a comment before. I’m actually quite a shy guy in real life, sorry about that! Keep up the great work and many thanks!

Sam, thanks for the kind words! I am glad the review was so informative for you. I always try to include as much information as I can reasonably find for each review. I included your original article in the links section as I enjoyed reading it myself! I’ll keep writing these reviews, if you do too! 🙂

Hi Mike, we got a deal, thanks so much! 🙂

How does it stack up against the EOS 650 and 620 from two years later?

I can’t honestly say as I’ve never shot either of those. I would think that them being fully electronic auto focus EOS cameras would mean that someone interested in a manual everything K1000 likely wouldn’t be interested.

My Minolta a7 just bit the dust and besides my XE-7 this is my next best film camera. I have two with differing battery compartments. So far it’s doing a fine job. Sharp as a tack using my 50mm 1.7. I kind of like sound it makes . Rather nostalgic.