This is a Walz Envoy 35, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Walz Company, LTD of Tokyo Japan from 1958 to around 1961. The Envoy was an up-level model of the earlier Walz 35 and came with an excellent 7-element Kominar lens, built by Nittō Kōgaku of Japan. Walz was a company primarily known as a distributor of photographic goods, and there is some debate as to whether or not they actually built this camera themselves, or had production outsourced to some other company. A well made camera, the Walz Envoy 35 was comparable to many other excellent Japanese rangefinders of the era, but sadly would be the company’s last, as they would go out of business in early 1961.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 4.8cm f/1.9 Nitto Kogaku S-Kominar coated 7-elements

Focus: 2.7 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Copal SVL Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M / X Flash Sync

Weight: 750 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/walz_envoy_35.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Walz Envoy 35 was a moderately priced Japanese rangefinder camera produced for a short time by Walz. Featuring a 7-element f/1.9 Komine lens in a well built body with great ergonomics and a solid viewfinder, the Envoy 35 represented a great bargain for photographers in the late 1950s when it was available. It’s bargain status still applies today as many of these cameras sell for fairly low prices online. The camera is easy to use and is capable of outstanding photographs, so if you have an opportunity to pick one up at a reasonable price, I highly recommend it! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, the complete package, its not every day you see a 7-element Sonnar | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.7 | ||||||

History

The name “Walz” has a long and complicated history in the Japanese optics industry, first appearing in 1936 as a model name of a folding strut camera that resembled the German made Foth Derby, and then again as a name alternative for a 6×4.5 “Semi” camera also sold as the Waltax by a company named Okada Kōgaku Seiki K.K. and distributed by a company called Nihon Shōkai. Both Okada Kōgaku and Nihon Shōkai are from an early, and very confusing, period of the Japanese optics industry where various “Camera Works” existed with fake names designed to hide the identities of the companies who either built or distributed them. In the first half of the 20th century, at least 17 different of these Camera Works appeared on various cameras and other photographic goods.

The name “Walz” has a long and complicated history in the Japanese optics industry, first appearing in 1936 as a model name of a folding strut camera that resembled the German made Foth Derby, and then again as a name alternative for a 6×4.5 “Semi” camera also sold as the Waltax by a company named Okada Kōgaku Seiki K.K. and distributed by a company called Nihon Shōkai. Both Okada Kōgaku and Nihon Shōkai are from an early, and very confusing, period of the Japanese optics industry where various “Camera Works” existed with fake names designed to hide the identities of the companies who either built or distributed them. In the first half of the 20th century, at least 17 different of these Camera Works appeared on various cameras and other photographic goods.

Whether or not Walz was a dummy company, or an actual entity with real employees in those early years is anyone’s guess, but a November 1952 advertisement for a trading company called K.K. Walz Shōkai with a Tokyo mailing address was the first real evidence that Walz was a bona fide company.

Between the years of 1952 and 1954, the company was largely a distributor for various other Japanese companies. In 1954, the company helped distribute cameras and other optical goods for Olympus. A large variety of photographic products like meters, filters, and self-timers were sold under the Walz name, but it is unlikely that they built any of these products themselves.

By the mid 1950s, various cameras became available featuring the Walz name such as the Wagoflex/Walzflex TLR, Walcon Semi 6×4.5 folding camera, and the Walz 35 rangefinder. There were several variations of each of these cameras, but most of them featured Kominar branded lenses which were produced by yet another Japanese company called Nittō Kōgaku K.K. Whether or not Walz designed or manufactured the rest of these cameras or relied on an unknown third party is anyone’s guess, and the debate continues to this day.

Regardless of who actually built these cameras, there is an undeniable link between Walz and at least three different Japanese companies in the 1950s, Tōgōdō Sangyō/Kōki, Nittō Kōgaku, and Daiichi/Zenobia Kōgaku. Whoever built them is really not as important as the fact that they were built at all.

Of course I wouldn’t be writing any of this if I didn’t have a Walz camera to review, and that camera is the Walz Envoy 35 which likely appeared in early 1959. As best as I can tell, the Envoy was an evolution of the original Walz 35 which first appeared in 1956, upgrading that model with a bright line finder and revised cosmetics. The Envoy was only available with a 7-element Sonnar formula f/1.9 lens built by Nittō Kōgaku. A variation of the Envoy 35, called the Envoy M-35 also existed that added a coupled selenium exposure meter.

Each of these cameras were likely only produced for a very short period of time as Walz would file for bankruptcy in April 1961. Despite a relatively unknown name and short production run, Walz seemed to have a pretty good distribution network in the United States, and several ads for the cameras appeared in various US publications in 1959 and 1960. Selling for $69.95, the camera was an incredible bargain for the time which made it cheaper than most other fixed lens rangefinders with a sub f/2 lens. When adjusted for inflation, that price is comparable to about $520 today.

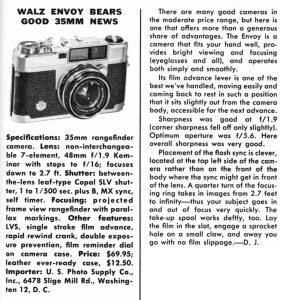

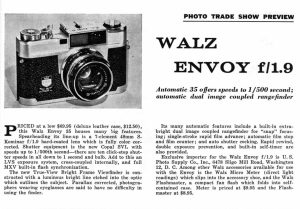

In addition to being an incredible bargain, the US press was fond of the camera, with comments like the ones in the article on the right from the May 1959 issue of US Camera which say the film advance lever is the best they’ve ever used, overall sharpness of the lens was very good, and that the bright viewfinder was easy to use even with eyeglasses.

In addition to being an incredible bargain, the US press was fond of the camera, with comments like the ones in the article on the right from the May 1959 issue of US Camera which say the film advance lever is the best they’ve ever used, overall sharpness of the lens was very good, and that the bright viewfinder was easy to use even with eyeglasses.

I couldn’t find any information about production numbers of the camera, but based on the small numbers available on auction sites today, likely not many were sold. I can’t imagine this had anything to do with any fault of the camera as it had a feature set and price combination that very few other companies were able to match.

Today, cameras like the Walz Envoy 35 are usually grouped into a very large category of good to great 1950s Japanese rangefinders. While the Walz Envoy 35 was well built and a good bargain, so were many other cameras of the era, and with the increased popularity of the Single Lens Reflex, it was likely very hard for cameras like this to stand out. In my opinion however, the Envoy 35 is a tick above the run of the mill Japanese rangefinder. With a 7 element lens, beautiful looks, and very good build quality, this is definitely a camera that collectors and users should take notice of the next time one comes up for sale.

My Thoughts

The first time I saw a Walz Envoy, it was in a cell phone pic of a display case that my friend Adam had sent me from an antique store near him. The seller was asking some exorbitant price for it, and after checking with the store owner, the price was firm.

As seems to happen with any GAS-afflicted collector, the Envoy never exited my mind, and it remained there for over a year until I saw one for sale on eBay. I can’t remember what price it was listed at, but it had my favorite option, the “Make an Offer” button. I threw out an offer and the seller countered. I was just about ready to click the “Accept Offer” button, then…whats this?! An eBay 10% off coupon on anything?! SOLD!!

The camera arrived in fantastic shape, as if it had hardly ever been used in it’s life time. It was in it’s original box, with the case, the manual, and original paperwork included. The lens looked great, the shutter fired at all speeds, the rangefinder was accurate, and the viewfinder was nice and clean. The body has quite a bit of heft, weighing over a pound and a half (750 grams), this camera was built before the days of plastic and other weight saving materials.

The large size of the camera means the top plate has a lot of room for all of the controls you’d expect to see there. From left to right is the rewind crank, accessory shoe, threaded shutter release button, rapid wind lever, and manually resetting exposure counter.

Engraved prominently into the top plate is the Walz Envoy 35 logo, serial number, film plane indicator and a “tattoo” of the 7-element Sonnar design of the Kominar lens. While I agree the quality lens was something for Walz to be proud of, I have to wonder how many users of this camera actually understood what this was supposed to be.

The bottom of the camera features only the rewind activation button and the 1/4″ tripod socket. The socket is reinforced into the main body of the camera for increased strength rather than stamped into the bottom plate like on lesser cameras. Also visible from the bottom is the self timer lever (indicated with a ‘V’) on the underside of the shutter.

Other than the viewfinder window, there is nothing to see on the back of the camera. To load film, you must first lift up on the door latch pin on the camera’s left side.

Opening the back reveals an ordinary looking, but well designed film compartment. Both shafts on the supply side are solid pieces of polished metal. There are two polished metal rollers, one on the supply side, and the other on the take up side of the door, that help maintain a smooth film transport. The film pressure plate has many small divots which are said to decrease resistance while film travels across it, further improving film travel smoothness. Just before the take up spool are twin polished metal sprocket gears covered by a black metal plate. Finally, the take up spool is a a fixed black painted spool with a single slit. While there’s certainly nothing groundbreaking in the film compartment, you can see that a lot of care and effort was put into it’s design.

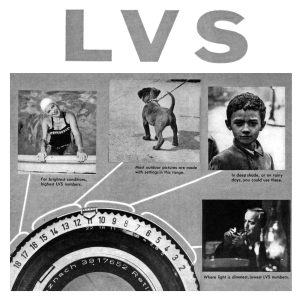

I really should just make a separate article about cameras with LVS systems and keep referring back to it, each time I encounter another camera with it. Until I do that, I’ll just repeat myself and say, “I do not like cameras with LVS”.

The term LVS, or Light Value Scale was introduced by F. Deckel in 1954 with the release of the Synchro-Compur shutter. At the time, it was an innovative way to simplify exposure calculation by having a consistent set of numbers or “Light Values” that could be transferred from a hand held light meter to a camera. If you had a camera and a meter that supported LVS, and your meter called for a value of 12, set your camera to 12, and you’d have a perfectly exposed image every time. Sounds great, right?

Well, for as well intentioned as the LVS was, how it was implemented by various manufacturers ranged from “meh” to downright hateful. Kodak AG’s system on folding Retinas is terrible. Overriding a set LV number was impossible to do with the camera to your eye, and difficult even at waist level. Making matters worse, if you didn’t have a meter and wanted to set focus based on rules like Sunny 16, you would have to fight with a small locking pin every time.

The LVS system on the Envoy isn’t the worst, but it still sucks. There’s two rings around the lens, an outer one that just controls the set LVS number, and an inner ring that allows you to choose various combinations of shutter speeds and f/stops that all match your set LVS number. So for example, if you choose an LVS of 12, you can choose between 1/30 @ f/11, 1/60 @ f/8, or 1/125 @ f/5.6. All three of those settings will get you the same exposure. But what if you wanted 1/60@ f/4 or some other combination? You have to fiddle with the LVS numbers until the combination you want shows up. Sadly, there is no way to just override the LVS system and choose the exact shutter speeds or aperture, you just need to deal with it. In fairness, you do get used to it after a while, but I’ve been using cameras with these systems for a while now, and I can’t find one implementation of the LVS that I’ve liked. They all range from mildly annoying to infuriating.

The Envoy’s viewfinder is large and bright with a contrasty rangefinder patch and projected bright lines with parallax correction marks. Unlike other companies that use tints of blue, yellow, or even green, Walz tinted theirs pink. I can’t be sure if this is how it was when it was new, or a symptom of age as the manual doesn’t mention it. In any case, it’s a pretty standard looking 1950s rangefinder. I would have expected a camera with this high spec of a lens, and a nice list of refinements to have a viewfinder with automatic parallax correction, but it’s omission is not a deal breaker.

The Walz Envoy 35 certainly gives the impression of a camera that’s more than the sum of it’s parts, but what was it like to use it?

I was pretty excited to shoot the Envoy for the first time, so I didn’t waste much time after acquiring it before taking it out shooting. For it’s first roll, I thought I’d try something different and loaded up a fresh roll of Kosmo Foto’s Mono 100 film. A panchromatic ASA 100 speed film Kosmo Foto Mono is a medium speed fine grained black and white film that is ideal when used in moderate light and with a sharp lens. And while it has absolutely nothing to do with the film’s performance, Kosmo Foto Mono comes in the coolest packaging of any film on the market! I figured what better lens than a 7-element Sonnar, so I loaded it up and carried the camera with me during a couple of weeks in late summer 2018.

Oh my! I’ve seen some nice images from black and white film before, but this roll of Kosmo Foto Mono was outstanding. I did miss focus on a couple shots and over exposed a few other, but I attribute that to rushing the process. But quite simply, the Walz Envoy 35 returned some of the sharpest, and nicest looking images I’ve shot in any camera in a while. The last time I remember being this pleasantly surprised by a camera was the Ricoh 519M.

Are these images characteristic of a 7-element Sonnar lens, is it because it’s a really nicely designed camera, or was it luck that on the days I was shooting it, I had some “good mojo”? Probably a little bit of all three. I was enamored with the camera’s good looks and it’s use while the film was loaded into it allowed me to painlessly shoot the entire 36 exposure roll without having to spend too much time thinking. I think that when you shoot a great camera, the shooting process is more fun, and that translates into better photos.

Of course, with all this praise over the camera and it’s lens, I should give some of the credit to the Kosmo Foto Mono 100 film. I find that 100 speed black and white film is the perfect sweet spot of minimal grain, excellent contrast, while still being fast enough that it can be shot indoors hand held. I don’t particularly love thick, grainy photos, so this is an emulsion that I plan on coming back to again in the future.

The Walz Envoy 35 is quite a special camera and one that I thoroughly enjoyed using. Nearly everything about the camera feels like a high quality instrument. The film transport is extra smooth, the focus dampening on the lens is neither too tight nor too loose. The Copal shutter fires with a satisfying “snick” with each press of the shutter release.

There is still some uncertainty about who actually built this camera, but regardless of the answer to that question, whoever did it, did a really great job. Not only is the camera very attractive to look at it, it feels like a very high quality tool in your hands. I have only two criticisms, the lack of automatic parallax correction in the viewfinder seems like a big miss for a camera with such a nice lens, but also the inclusion of the LVS system frustrates me.

Neither are deal breakers though. The lack of automatic parallax correction likely was a casualty of keeping the camera at such a low price point, and the LVS system was ‘status quo’ for nearly every rangefinder of the 50s, so I can’t really blame them for including it.

Walz was not a major player as a camera maker, and they went out of business shortly after the release of this model, so there likely weren’t a ton of these sold, and therefore not many show up for sale today. But when they do, if you were on the fence about whether or not this camera compares favorably to other makes and models of the era, I am here to tell you that yes, it absolutely does!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Walz_Envoy_35

http://www.kitamura.jp/photo/repairer/2010/re488.html (in Japanese)

This was a good article. Walz is an interesting company, but not much can be found on the net about it(s history). I have their shade & filter sets for Nikon S models, Contax and Retina lines. Quality is very good. I also also have one of their basic TLRs, that is not so good, definitely not on par example with Yashica’s economy models.

I’ll second everything you said. I found mine at a resale shop, after I got home realized I had seen a camera bag with accessories. Someone had split them up. I went back the next morning and worked a deal. So I have a very complete and clean example with all of it’s “extras” and it’s a wonderful little camera. In fact, I think I might take it out this week!

Betty, thanks for the kind words, and Im glad I was able to inspire you to take yours out again. Hopefully you got that bag the next morning for a good price as they’d be unlikely to sell the accessories for much without the camera!

Thanks for this review – it was my first real camera, and I still have it. It still works perfectly. You are spot-on in noting that it was a cut above – that lens is exemplary for that price point. Built with precision, very solid. Glad to see its praises sung to a vintage film camera loving audience. I used it a lot, then it got sidelined when I got my first SLR. Now I enjoy running film through it once a year. Would do more often if I hadn’t collected so many other great cameras.

David, thanks for the kind words, and it’s great to hear that another is out there in good working order. I’m glad you are still able to use it on occasion. With the number of cameras in my collection, it can be hard to find the time to revisit some of them, but the Envoy definitely has earned the distinction as one I’ll definitely shoot again!

Glad to see another great camera review from you, Mike … I thought we’d lost you from the analog community. My late father and I shot a lot of 8mm home movies, all of which I’m hoping to have transferred to digital soon as the $$$ allows. In the meantime, I found a very high-quality 8mm action editor with the Walz brand name on eBay for about $15. The thing is all-metal, with a bright screen, and beats the Mansfield editor I formerly used. Top-quality construction, just like your Envoy camera. On the subject of b&w film, may I recommend Ilford Pan F Plus, ISO 50, as an excellent emulsion for sunny days and old rangefinders.

Yes, I got punked by your April Fools “heavy metal music” post. Sheesh …

Walz certainly had a good variety of photographic related products. Their filters, hoods, meters, and other things are pretty common in the collecting world, but they weren’t as well known as a camera maker, which is where the debate arises as to whether they actually made any of these cameras themselves. We know they contracted out the lenses, so it’s plausible they did the same for the rest of the camera, but who?!

Mike, I’ve read this page several times, and recently recognized your text in a listing on ShopGoodwill.com — thought you might be interested: https://www.shopgoodwill.com/Item/77199681

Haha! I’m famous! Thanks for sharing!

Oh, I see they did give you a link. My first impression was that it was uncredited.

According to Nitto Kogaku’s own website (https://www.nittohkogaku.co.jp/en/company/history.html) they started producing finished cameras in 1961. This suggests that they may not have produced the Walz camera (at least not initially) though they did supply the lens, at least. I don’t know if they made camera components before 1961 to be assembled elsewhere.

Kominar is Nitto’s own lens brand, which is not to be confused with Komine Company, Ltd., a different manufacturer.