This is a Baldessa Ib, a 35mm rangefinder made by Balda Kamera-Werk in Bünde, West Germany starting in 1958. This was the third, and best featured of the original Baldessa lineup, improving upon lesser Baldessas with a coupled rangefinder and uncoupled selenium exposure meter. The camera was well built, but had several quirky controls such as a front mounted focusing wheel immediately below the meter, and a bottom mounted fold out winding “key” for advancing the film and cocking the shutter. Later Baldessas would be cheaply made, entry level models, leaving the Ib as a bit of a middle tier model in a generally low end lineup.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/2.8 Balda-Werk Bünde Baldanar coated 4-elements

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: Prontor SVS Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate LVS readout

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 588 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/baldessa.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Baldessa Ib is an unusually nice camera designed by a company not known for high end cameras. It has a compact body with several unique features such as a front plate focus wheel, a fold out film advance key, and a front shutter release. Combined with a capable shutter, 4-element Baldanar lens, and a bright viewfinder with a coincident image rangefinder and automatic parallax correction, the Baldessa Ib is quite capable. I thoroughly enjoyed shooting mine and think that it’s combination of good looks, performance, and ergonomics make for a very interesting camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, a very capable camera with some quirky controls that is immensely fun to use | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.7 | ||||||

History

In 1897, a German mechanic named Max Baldeweg moved to Dresden to seek work in one of the many industrial companies in that area. After a couple of years, Baldeweg had developed an interest in photography and in November 1908 opened his own company which produced and sold a variety of photographic accessories such as vignetting machines, film pack cassettes, and photographic blinds.

In 1897, a German mechanic named Max Baldeweg moved to Dresden to seek work in one of the many industrial companies in that area. After a couple of years, Baldeweg had developed an interest in photography and in November 1908 opened his own company which produced and sold a variety of photographic accessories such as vignetting machines, film pack cassettes, and photographic blinds.

Baldeweg’s company was quite successful and by 1912 opened a second factory and changed the name of his company to Fabrik Photografischer Artikel Max Baldeweg. Around that same time, Baldeweg started using the “Balda” trademark on several of his products, and the very next year changed the entire name of his company to Balda-Werk Max Baldeweg.

Over the next decade, Balda-Werk expanded it’s business, producing a large number of products in support of the photographic industry, but it wasn’t until 1925 that the company produced it’s first commercial camera, a simple box camera called the Balda Box.

As the years went on, Balda cameras increased in quality and complexity. Supplementing the company’s popular line of box cameras were folding roll film cameras, and then eventually compact 35mm scale focus and rangefinder cameras like the Baldina and Super Baldina that would compete with the Kodak/Nagel Retina series. Balda-Werk earned a reputation as one of the Dresden area’s premiere camera companies.

Around 1940, along with nearly every other German company, production of cameras was halted to support the German war effort. Balda produced a variety of optical goods such as altimeters and variometers for military use. During the bombing of Dresden in February, 1945, Balda’s factories were heavily damaged and required extensive repairs after the war.

As soon as the war ended, reconstruction of Balda’s factories began, and Max Baldeweg returned as owner but left the day to day decisions up to a man named Willibald Lauterbach. Hampered by their reconstruction efforts, Balda’s first post-war products were children’s toys and simple household goods.

During this time, Soviet occupation in the Dresden area was quickly taking control over German owned businesses, turning them into state owned enterprises, or VEBs. The Soviet occupation forces were very suspicious of anyone they considered even remotely critical of their new regime, and for reasons I could not uncover while researching this article, in June 1946, both Max Baldeweg and Willibald Lauterbach fled East Germany, abandoning their company, and relocated to East Westphalia in Allied controlled West Germany.

After their departure, the East German Balda started producing a simple clone of the Compur shutter called the Ovus. This shutter would be the foundation for later Cludor and Vebur shutters which were commonly used in East German cameras. In 1950, Balda was absorbed into VEB Zeiss Ikon and in 1951, was renamed VEB Belca-Werk. Belca-Werk produced mostly inexpensive folding cameras for a few more years before being fully absorbed into VEB Kamera-Werke Niedersedlitz in 1956. One exception to their run of cheap cameras was the Belca Belmira, an unusually shaped rangefinder camera that debuted in 1953, but would later be sold under the name “Welta” after the dissolution of Belca.

Out west, after settling in Bünde, West Germany in the late 1940s, Max Baldeweg formed an all new Balda Kamera-Werk. The new Balda company’s first products were simple folding medium format and 35mm “white label” cameras that were sold as house brands for German retailers such as Foto-Quelle and Porst. By the early to mid 1950s, Balda improved their designs, creating more advanced versions of the prewar Baldina, and eventually moving onto non-folding designs like the Baldessa, Baldamatic, and Super Baldamatic.

Balda’s non folding 35mm cameras would prove to be the pinnacle of the company’s camera development. The simpler Baldessa I was introduced in 1957 and was a meterless scale focus camera with a simple 3 speed Vario or Prontor shutter and one of three different triplet lenses. Shortly after it’s release, the Baldessa Ia would debut with a coupled rangefinder and better lens and shutter combinations.

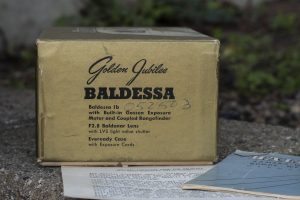

Finally, in 1958 to commemorate Balda’s Golden Jubilee (or 50th Anniversary), the Baldessa Ib would debut, adding an uncoupled selenium exposure meter to the specs of the Ia. The Golden Jubilee Baldessa Ib would retail in the United States for $79.99 which when adjusted for inflation, compares to just over $700 today.

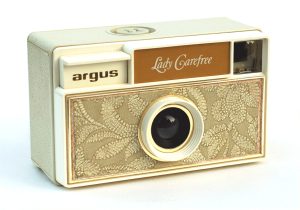

By the 1960s, due to massive pressure by the rapidly expanding Japanese camera industry, companies like Balda found it harder and harder to stay competitive. Balda’s offerings in the 1960s became increasingly simpler and cheaper, eventually creating cheap copies of the Minox 35 series and cameras like the Argus Lady Carefree.

Today, Balda cameras often go under the radar of most collectors. This was a company that at no point in their history ever innovated any unique feature or design. While their products were generally well made, they never aimed high enough for most people to notice. Further adding to the general feeling of ambivalence towards the company, was their frequent production of unbranded cameras that were sold by other companies. With that said, some models like the Baldessa Ib being reviewed here are quite nice little cameras that come with them typically good German build quality and a quirky design which aren’t quite as deserving of the “meh-ness” of their other models.

My Thoughts

In a recent article, GAS Attack! Buying Cameras on eBay, I offer several suggestions on ways to get the best prices while shopping for cameras on eBay. One of those suggestions was making an offer to a seller even when the ‘Make an Offer’ option is not selected. This Baldessa Ib is one such camera where I successfully employed that tactic. I don’t remember the exact price that the seller had, but I put this camera on my watch list for two 7 day auction cycles, and it never sold.

Right before the auction was to end the second time, I contacted the seller and nicely explained that I had been watching the item and asked if they’d consider my offer of about $20 below the starting price on the auction. They responded and said they would, but only if it didn’t sell. As fate would have it, the auction ended with no bids, and I got a message from the seller saying they’d relist it with a Buy It Now of my requested price and to let them know if I was still interested. I was, and after a quick purchase, the camera was mine.

As promised in the listing, the camera was in pristine condition coming in it’s original box with a case, lens cap, and original paperwork. The lens and viewfinder were both crystal clear, the shutter worked at all speeds, and the light meter responded to light and appeared to be accurate. It’s as if this camera had never been used.

Moreso than it’s condition, I was immediately drawn by how compact and comfortable the camera felt in my hands. The general shape of the camera is similar to the AGFA Optima series, but it’s soft rounded corners enhanced it’s feel. The position of the front shutter release was in the perfect location, immediately below the metal focusing wheel which was also very comfortable to use. The camera’s shape and size make the camera feel lighter than it’s actual 588 gram weight suggests.

The bottom of the camera is unusually cluttered, especially for such a compact camera. What looks to be a film advance lever on the left, is actually the rewind knob with a fold out, curved handle. When the end of a roll of film has been reached, you must slide a little lever from the “T” position to “R”. In doing so unlocks the film transport so it can be rewound, but also causes the folding handle on the rewind knob to pop out. In the center of the rewind knob is a round post with a red line on it. This red line is a film transport indicator that shows when film is moving onto or off the take up spool.

Surrounding the 1/4″ tripod socket is a sharply textured ring that turns a film reminder disc beneath it. This ring is just for information only, and has no effect on the meter.

On the opposite side of the rewind lever, is perhaps the camera’s most unique feature, which is the fold out film advance….thing. I don’t know what to call it, as it’s neither a knob or a lever. When folded out, it’s almost like a wind up key on a music box. Before every exposure, you must fold out the handle and rotate it until it locks in position, ready for the next shot. At the base of the handle is the exposure counter, along with an exposed saw tooth dial which is used to reset the exposure counter when installing a new roll of film.

To install a new roll of film, you must release the lock for the camera’s removable back by pressing in two buttons on the camera’s right side.

The entire back of the camera comes off to reveal the film compartment. Film transport is backwards of most 35mm cameras and goes from right to left. The take up spool is fixed and has a large slit for attaching the film leader.

In order to install or remove a 35mm cassette, you must have the rewind lever pulled out, which moves the little fork that engages the spool inside the cassette out of the way. In the image to the right, I do not have the rewind knob in the correct position for loading in a new cassette so if you are trying to load (or unload) film into a camera like this, make sure the rewind lever is out. Like most 1950s cameras, there are no foam light seals around the edges of the film compartment, so there is nothing to scrape off and replace.

As with most leaf shutter cameras, shutter speeds and aperture values are changed via rings around the shutter itself. The Baldessa Ib uses a LVS system which is one of the better ones I’ve used, because it is very easy to override, allowing you to easily set any combination of shutter speed or f/stop that you wish.

The LVS numbers are printed on the side of the shutter near the shutter release and allow you to choose any number from 2 – 17, but once you’ve locked in on a number, you can easily pick any combination of shutter speed or f/stop using the appropriate ring. Beneath the LVS numbers is a small lever for changing between M and X flash sync, or activating the camera’s self-timer (V).

The viewfinder opening on the back of the camera is surprisingly large and bright, especially for a camera released in the late 1950s before large and bright viewfinders were a guarantee. Wearing prescription glasses, I had no trouble seeing the entire viewfinder image.

Looking through the viewfinder reveals an easy to use circular rangefinder patch with projected frame lines to indicate the 45mm focal length of the length. A nice addition is that unlike many inexpensive cameras of the 1950s, the Baldessa Ib has automatic parallax correction in which the frame lines change position as you change the focus distance of the camera. As you get closer to the minimum focus distance, the lines correct parallax error that is common in rangefinder cameras.

Handling the Baldessa is a unique experience. The camera’s compact size, rounded corners, and creative placement of critical controls result in a very unique shooting experience. As we’ve seen, unique isn’t always good, as there’s a reason why most cameras keep their controls in the same locations, but it’s clear to me that the designers working on this model in Bünde put a lot of thought and reason into why they made the decisions they made. This is a fantastic camera that has an excellent feel in your hands and it has a very good viewfinder. But what kinds of images is it capable of?

My Results

My go to color film when shooting a new camera for the first time is usually Fuji 200 or 400 as I have a ton of it and it’s cheap. I generally reserve more expensive emulsions for cameras that I am certain will work, but with the Baldessa, it was in such fantastic condition I gambled with a fresh roll of one of my favorite films, Kodak Portra 160. I love Portra for it’s subdued, but natural colors. I also find that Portra handles post processing a bit better than other color films, allowing me to tweak the saturation or vibrance a little better, without making the images look noticeably fake.

As I had hoped, the Balda rewarded me with a roll of 36 beautiful color images from the Portra 160 film. I shot most of the roll outdoors in early fall of 2018, but even the interior shots like the one of the train car had colors that were natural and smooth. Portra seems to return the best blues in sky shots of any film I’ve used, there’s no cyan or greenish hues to speak of, only the colors I remember seeing when I took the actual photo.

In an effort to not turn this into a film review, I must say the Balda did exceedingly well. Not only is the camera well built and fun to shoot, it’s images are a notch above the low to mid range cameras that Balda was often associated with. The 4 element Baldanar is every bit as good as any other 4 element Tessar clone or double anastigmat lens that would have come before it. In fact, based on the images themselves, if you had told me this was a higher spec 5 or even 6 element Zeiss lens, I wouldn’t have doubted you. The only flaws in the lens are seen near the corners when shot wide open (see the child in the stroller and train car images), but stop the lens down even one stop, and this goes away. From f/4 and smaller you get corner to corner sharpness without any noticeable optical anomalies evident on lesser lenses.

Balda chose the Baldessa Ib to commemorate their Golden Jubilee (50th Anniversary) and what a great choice it was. This was a handsome camera, built with typically high German quality, an excellent viewfinder, a very good viewfinder, and a very good lens and shutter combination. It’s design was unlike other cameras of the time, but not so strange that it would be difficult for someone to quickly pick up and start using.

The Baldessa Ib represents many of my favorite qualities in a vintage camera. It’s design, ergonomics, and images check all the right boxes for me, and to have found an example in such great condition was icing on the cake.

If it’s not clear by now how much I love this camera, I’ll clearly say it. I loved this camera. Maybe you won’t appreciate it’s quirks as much as I do or find it’s use to be much different than 100 other German or Japanese rangefinders from the 1950s, but I would be willing to bet that even the most jaded collector wouldn’t find at least something to like about this camera.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Baldessa

https://www.35mmc.com/23/01/2019/balda-baldessa-1b-review/

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/8779-balda-baldessa-1b-i-think-i-am-in-love

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/the-beautiful-baldessa-from-bunde.488970/

https://simonhawketts.co.uk/2016/12/17/balda-baldessa-1b-35mm-rangefinder-camera/

Mike, I love your research on the history of Balda. I have not seen many Balda 35mm, and am mostly familiar with the folders, which are not bad. Nice review of an unusual camera!

Thanks for the compliment! I enjoy seeing whatever I can dig up about these lesser known models.

Mike, this is a great, and underestimated, little camera, IMO.

I got mine off ebay for just £10, inc. case around two years ago. I already had a Baldalux 120 folder, but whilst the brand name is well known to me, I knew nothing about their 35mm cameras. I like cameras with coupled rangefinders that work (!) and whilst a working built-in meter is a bonus, they often don’t and it isn’t a great loss.

What surprised me, over the very good build quality and finish for a brand not that highly regarded, was the coupled frame lines

and the clear rangefinder spot. It all works perfectly, so you may imagine I was delighted with my £10 purchase.

I’ve had a couple of Baldamatics with Xenar lenses, but the rangefinder in these is not as good as the 1b, as these use front cell focusing, whereas the 1b is a unitary lens focus, so the whole shutter mechanism moves.

Terry, you bring up a good point that I failed to mention in the review in that the unit focus moves the entire lens and shutter assembly, as opposed to front cell focus like on lesser cameras. This design is a superior method in that the lens elements remained in an identical orientation at all focus distances, eliminating any distortion related to lens elements moving independently of each other! Another reason to champion this great camera!

Mike, I’ve long held a niggling doubt about the two focusing methods. Technically, I feel that unitary focusing lenses must be better because the lens’ elements relationship remains fixed. However, I’m also aware that all lenses can not be optimised over their full focusing range and optical quality will drop off either side of the optimum determined by the manufacturer. For example, one lens that I know of and have personal experience of, is the first Leitz f2/50 Summicron in Leica screw mount and where Leitz recommended that the lens be used at intermediate distances for optimum results. An extreme example of this is, of course, a macro lens, where overall performance can be expected to fall off over increasing distances. The reality is, though, with any well designed quality optic, the differences are probably hidden by our own technique!

And just in case any Leica 60mm macro lens users happen to read this, the overall performance of this lens leaves very little to be desired and even led to Leitz suggesting it could be used with equal aplomb as a 50mm substitute, so good is its performance, even at infinity.

You’re right in that no focusing lens can be 100% perfect at all focus distances, but when comparing unit focus to front element focus, rotating and moving a single element or group of elements independently of the rest of them is a huge challenge for the optical designers to maintain good performance. While it’s certainly “good enough” for most people, unit focusing lenses are definitely more ideal for sharpness.

A nice clean model with the box, I’m jealous—I want one! Thanks for the great review!

Just found one of these at an estate sale for $10. Seems to be working and the meter is accurate. I’ve been having fun shooting my selenium meter cameras this summer, after finally getting some that are functioning. This Balda, a Kodak Signet 80, and a fujica rangefinder, and I found a working meter to use with my Argus c33 and Argus c44r and C4r.