Camera technology and photography has changed massively over the past 100 years. When you consider at the turn of the last century, amateur photographers were using cardboard box cameras, and 50 years after that, they were using Argus C3s with coupled rangefinders, interchangeable lenses, and the ability to shoot film that gives you up to 36 exposures on a single roll. To the average photographer in 1900, this technology from the 1950s would have seemed like science fiction!

Fast forward to today, and the technology we have now compared to that same guy or gal shooting that Argus, seems downright archaic compared to the digital mirrorless cameras with 100+ point auto focus systems, 3 inch (or larger) swing out LCD touch screens, and the ability to shoot thousands of images and never have to develop film.

Yet, for all of these advancements, I still enjoy using those old cameras with their rudimentary feature sets. I enjoy slowing down and stepping back into the shoes of a photographer from half a century or more ago and using a fully mechanical camera with automatic nothing….mostly.

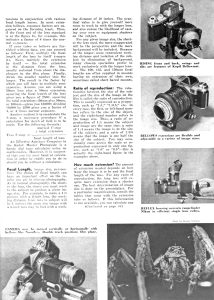

The exception to this is when it comes to macro or closeup photography. Most 35mm rangefinder cameras can only focus down to about 3 feet without some type of closeup filter or proximeter installed. SLRs with non macro prime lenses can often go down to about a foot and a half, but if you want to get closer, you have to start adding extra equipment like bellows or extension tubes.

While bellows and extension tubes are still options for digital photography today, they’re not as necessary as many cameras have dedicated macro modes. Even for those who don’t, when you use a closeup lens or extension, the CPU controlled auto focus sensor usually handles the focus for you. My FujiFilm X-T20 has a common feature called focus peaking in which the sharp edges of an in focus image are highlighted on the viewfinder in red making closeup photography a snap!

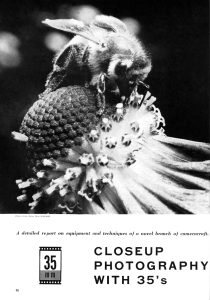

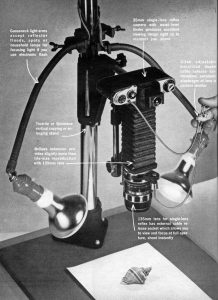

This wasn’t always so, and that’s why this week, we’re taking a look at an article that first appeared in the September 1957 issue of Modern Photography that discusses methods for achieving closeup shots using 35mm cameras. Reading this article, it made my head hurt. Not so much that I am incapable of using the devices shown, but when you consider using a vintage film camera is already a slower process that requires more concentration and appreciation for fine details, and that the cameras of the day have darker viewfinders that are harder to see through than modern digital cameras, the prospect of me setting up a copying stand with bellows attachment and setting up auxiliary lighting just to take a picture of a bug seems really intimidating.

I’m sure there will be those that scoff at my trepidation for what was once “business as usual”, but like I said, I do appreciate the nature of old cameras, but I think this article reveals that I have my limits. While I am sure that when executed perfectly, getting a great macro shot on film is a very rewarding experience, it’s just not something that interests me.

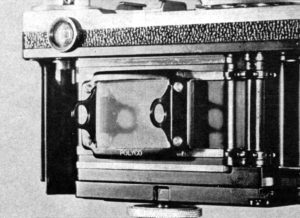

But therein lies my fascination with it. Throughout my experiences with these older cameras, I’ve learned to appreciate that things like an auto returning reflex mirror, open aperture metering, and double image prevention are features that weren’t always taken for granted, but with macro photography, the gap between how it used to be, and how it is now, is even greater than I would have ever imagined! A ground screen attachment on the back of a Nikon rangefinder! Are you kidding me?

If anyone reading this article has ever captured macro photography successfully using the methods below, I take my hat off to you. Congratulations sir or madam, you have way more patience than I, but the next time you see me out in my garden trying to get that perfect shot of a bee pollinating a flower, I’ll be there happily with my digital mirrorless camera shooting in continuous burst mode while staring at the rear LCD screen hoping that at least one of those shots is good!

If you like history and like seeing the hoops photographers had to jump through to take pictures of bugs and flowers, check out the article below. There’s Exaktas, Praktinas, and even Alpas with all sorts of bellows, extension tubes, and other gadgets for your viewing and reading pleasure. Take a look at the Praktina with bellows attachment on the 4th page as I was able to recreate that same setup in my image earlier in this article!

If one article of looking at scary equipment taking pictures of bugs isn’t enough, I found another. This time, its from the August 1960 issue of Modern Photography, and this one was written by Herbert Keppler himself!

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2019.

“I’ll be there happily with my digital mirrorless camera shooting in continuous burst mode while staring at the rear LCD screen hoping that at least one of those shots is good!” Mike, this is what separates the men from the boys, :D) or those that worked tirelessly to acquire the skills set necessary to succeed.

Of course, this is an unfair comparison. Had those photographers had access to the modern world of digital cameras, life would have been so much easier for them. Today, one still needs a certain level of skill to produce excellent results, but it is far easier with a digital camera with its relatively large live-view screen and very accurate exposure. Plus, a good practical knowledge of lighting is often needed.

I always admired those that could do it, recognising from my own attempts what a difficult subject close-up and macro photography was. But for many who lived through and were brought up only knowing film, all that equipment wasn’t seen in the same way as modern eyes view it; all the contraptions were a means to an end and, importantly, were seen as making a difficult task easier. And owning a rangefinder wasn’t necessarily a hindrance as Leitz had its very versatile Visoflex units for both screw and M mounts. Zeiss also had something similar for its Contax.

Funnily enough, I believe in many ways that old kit is just as viable today, just attach it to a digital camera. In fact, a number of bellows came with a slide holder, so for those wanting to copy slides, a bellows + slide attachment would be a good acquisition.

I agree, had modern technologies existed back then, people would have definitely embraced them. There are those who look down upon people who digitally manipulate their photos, but I don’t. I feel like a photographer should be free to use whatever technology and tools that are available to get the result they wish. My comments in this article is that while I love the history behind old cameras, and I often enjoy trying them out to see what kinds of results I can get, I have my limits. Macro photography is hard enough even with modern digital tools. Doing it on film with all of these accessories is truly beyond my skill (and patience) level! 🙂

Being a geezer, I’ve had experience shooting macro with a manual diaphragm lens reversed on a bellows unit, mounted on a Pentax H3V. Correct focus and desired depth of field were not too difficult to obtain, but correct exposure was an issue. The solution was to bracket, shooting five frames to get one that would print up well. Lighting was also a challenge: Remember that wet processing requires burning and dodging to correct bright spots and bring out shadow details.

.

There was no such thing as HDR layering, just your hands, a wand with a disk of paper on one end, and another piece of paper with a hole in it. Each finished print required a series of test strips, exposed and developed one by one. I’m talking about black & white, BTW, where control rested in my hands. Color shots presented vastly different problems, as tricks like burning and dodging changed the print’s color balance in the areas where those tricks were employed. Add to that the several steps (and time) it took to process a test strip, and you understand why most macro work in the goold ole days was in b&w.

The film plane ground glass critical focusing aid you show for a Nikon S also existed for (believe it or not) double 8mm movies. I have a ground glass with magnifier device that was made by Kodak for use with their 8mm magazine-load Reliant cine cameras. You’d pop out the film magazine from your tripod-mounted camera, insert the focus device, make sure everything was good, and reinsert the film (losing a couple of frames in the process). Macro shots were not really possible with “D” mount lenses typically found on Reliants, but one could obtain critical focus on subjects as close a 3 feet away from the lens.

My God! Ground glass focusing on a motion picture camera is even more ludicrous than a still camera! It’s so impressive to me the hoops people would jump through back then!

Mike. I’d overlooked Roger B’s comment re cine. I’ve still got the Double-8 cine camera I owned in the mid-1960’s, it’s a GB-Bell & Howell Sportster C with a tri-lens turret with 3 TT&H lenses, considered some of the best of their day. Conventional viewing was via an optical viewfinder lens on the turret, but down the right hand side of the body is a viewing scope with magnifying lens and which has a ground glass screen. Any lens could be rotated to this screen for critical focusing before then being moved into the taking position.

Given how much the miniscule frame was enlarged when projected, focusing errors became even more noticeable. Hyperfocal distance focusing was fine with the w/a and standard lenses, whose focal lengths range from 5.5mm to 13mm, but at shorter distances a mid-tele of 25mm and a standard fitted tele of 36mm to 38mm focusing really was critical.

The first barrier to be crossed was the “3.5 foot minimum” of fixed lens and rangefinder cameras. This was broken by a Topcon RE Super that got me to 18 inches, which was interesting but not quite close enough to capture details in insects or flowers.

Closeup lenses were limited by unsharp corners, but were affordable. The Nikkormat FTn and a 55mm f/2.8 Micro-Nikkor got me to 1/2 life size, along with Nikon Bellows 3. Working distance became a problem, as insects ran or flew away, which led to adapting a 80mm f/5.6 EL-Nikkor enlarging lens to the Bellows 3.

The Vivitar Series One 90mm f/2.5 was on the permanent wish list until the Tamron SP 90mm f/2.5 arrived in Adaptall2 mount allowed me to use it on, say, a Pentax ME Super or Canon EF.

This eventually led to the Nikon PB4/PS4 as slide- and negative-copying became necessary. (I even tried my hand at copying black-and-white negatives into “slides” via Kodak High Contrast Copy film souped in Dektol 1:1!)

The final frontier was reverse mounting a 28-70mm zoom lens on the PB4, with a Capro (Sunpak) RL-80 fired off with a double cable release. Why this unwieldy package? I took Kodachrome 25 slides for an Orchid Species club, which featured 5mm or 10mm blossoms. I had to do this on location, in a storeroom, sometimes on a tripod, but occasionally handheld, when necessary…at night, under artificial light.

Could I have adapted a Cine lens? Maybe, but this was “casual photography” using available equipment in the 1980’s. These were fun times back before digital cameras made things (somewhat) easier.;)

Interestingly, I’ve got two Yashica Dental Eye cameras and which, as their name suggests, were intended for dentists to be able to take images of patients’ teeth, including within the mouth. The models came with a 55mm or 100mm non-interchangeable lens, and can photograph continuously down to 1:1. Focus range is restricted to 1:10 in the case of the 55mm and 1:15 for the 100mm, so they are not all-rounders. These cameras could easily be pressed into service for macro photograph as the they incorporate built ring flash units, with little modelling lamps, and as the aperture is coupled to the focus/magnification setting, correct exposure is virtually guaranteed.