This is a Canonflex R2000, a 35mm SLR made by Canon of Japan and was produced between the years 1960 and 1964. The Canonflex R2000, along with an economy model called the Canonflex RP both replaced the original Canonflex from 1959 which was Canon’s answer to the Nikon F. It was not only Canon’s first 35mm SLR, but it was also their first camera created specifically for professional photographers. Despite being a well made camera with some innovative features, it could not compete directly with the Nikon F, and combined with a poor lens selection upon it’s release, did not sell well. Of the entire Canonflex series, the R2000 is the least common, with an estimated 8800 ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Super Canomatic R coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Canon R-Mount Breech Lock Bayonet

Focus: Variable

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/2000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None, Available Clip-On

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M and X Flash Sync w/ Canon V Flash Connector

Weight: 998 grams (w/ lens), 705 grams (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/CanonflexR2000Manual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Canonflex R2000 was a subtle update to the original Canonflex which was Canon’s first ever SLR. It was aimed at professional photographers and tried to compete with the Nikon F, but failed to catch on due to Canon misunderstanding the needs of a professional photographer and an anemic selection of lenses at launch. Despite the Canonflex’s reputation as a sales failure, it’s a very nicely built camera that has a unique feel and look to it. The overall package is that of a capable and fun to use camera, even if no one bought it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 as Canon’s first pro SLR | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

Introduction

This review of the Canonflex R2000 is the 200th camera review I’ve written on this site. This is a milestone that I never would have imagined I would hit when I wrote my first review for the Argus C3 Matchmatic back in December 2014. While I still assert that I write these reviews because I enjoy writing them, I also know that many of you appreciate the effort I put into each and every article.

There is no possible way I could have written 200 reviews, plus a large number of Keppler’s Vault and other articles without the help and inspiration of those who read my site.

When I realized I was coming close to my 200th review, I wanted to find a camera that had 200 in it’s name, and while there are a few, there weren’t any that I could easily get my hands on and were interesting enough to write about, so I chose this Canonflex R2000 because you know, 2000 is kind of like 200. At this rate, I should hit my 2000th review in 45 years!

In any case, I wanted to dedicate this article in memory to Peter Dechert who passed away in November 2016. He was a life long photographer and camera historian. His books on the Canon Rangefinder and Canon SLRs are considered by many to be authoritative works on each subject. I’ve personally referenced his books on previous reviews I’ve written, and much of the research in this very article was taken from Peter’s book on the Canon SLR. I never got to meet Peter or speak to him, but of the people I know who have, they consistently had nothing but positive things to say about him.

Quite a bit of the information in this article was taken from Peter’s Canon SLR book, “Canon: Single Lens Reflex Cameras 1959-1991”. Although first published in 1992, it was released by Peter to the public domain in 2007 and is available here, free of charge for personal use only.

History

The year was 1955. With the excitement and exposure generated by companies like Nippon Kogaku with their Nikkor lenses and Nikon cameras and Canon with their Serenar lenses and Leica screw mount cameras, the Japanese camera industry was expanding at a breakneck pace.

Nippon Kogaku and Canon had each just released the Nikon S2 and Canon IVSb2 models respectively, and while each were very well built and feature rich cameras that greatly evolved from the original German designs they were designed to compete with, Ernst Leitz of Germany had also just released the Leica M3, arguably the world’s best 35mm rangefinder ever made.

For as good as the Nikon and Canon rangefinders were, the Leica was more advanced and sold better. Both Nippon Kogaku and Canon realized that staying competitive with the Germans would require significant investment into new features for their next models and work began on what would eventually become the Nikon SP and Canon V and VI series.

While the 35mm rangefinder battle was raging, there was a new competitor that had been lurking in the shadows of rangefinder popularity, the Single Lens Reflex.

At this time, 35mm SLRs were not new as models like the Ihagee Exakta and KW Praktiflex had existed prior to World War II. These early 35mm SLRs were complicated devices that had several technical shortcomings that made them unappealing to many professional photographers, so they always played a sort of specialized role in photography.

While the world was watching Germany and Japan duke it out in the 35mm rangefinder arena, companies like KW, Zeiss-Ikon, Asahi Pentax, and Miranda were quietly releasing innovative 35mm SLRs that slowly bridged the gap between what professional photographers expected from rangefinders, and what SLRs could deliver.

When Nippon Kogaku and Canon each started working on their upcoming rangefinder models, the world was starting to realize that SLRs would one day equal, and even exceed the capabilities of rangefinder cameras. Nippon Kogaku saw this as the writing on the wall for the 35mm rangefinder, and began simultaneous development of the Nikon SP with their as of yet unnamed Nikon SLR camera. Canon on the other hand chose a different path.

Before I go too far, it’s worth noting that Canon first dipped their toe into the SLR pond in 1955 with the release of two telephoto lenses (100mm and 135mm, both f/3.5) lenses using the Exakta lens mount. These two lenses are both indicated by the letters “EX” written on the name ring. Although these lenses are unrelated to the later Canonflex, their existence suggests that Canon was keeping an eye on the SLR market.

Development of Canon’s first SLR began after the release of the Canon VL in August 1956. The design of the new camera was influenced by the VL, including it’s bottom mounted film advance trigger. Early prototypes of the camera had a control layout similar to that of the VL, although it’s less obvious in the final version as many changes occurred along the way.

The lens mount for the upcoming Canon SLR was a revised bayonet style breech lock mount that Canon first used on the Seiki-Kogaku X-Ray camera from 1939 in which the lens mates to the body of the camera, and a locking collar on the lens rotates to lock the lens into position. This method for attaching a lens was thought to be superior to traditional bayonet style lenses because the surfaces of the lens and camera never rotate against each other, eliminating any type of wear of the mount which could cause focusing errors over time.

The Canonflex was in development for about two and a half years and finished examples began to roll off the assembly line in early 1959. The camera would make it’s world debut in May 1959 at the same time as Nippon Kogaku’s Nikon F.

The Nikon F would end up being a huge success, staying in production until 1974 with a grand total of over 862,000 made. It singlehandedly ushered in a new era of SLR cameras, one that Nikon still dominates to this very day.

The Canonflex on the other hand, was a sales failure. According to Peter Dechert, less than 17,000 of the original Canonflexes were produced between May 1959 and May 1960. A revised model called the R2000 would go on sale in September 1960 which upped the top shutter speed to 1/2000 and had a couple other minor changes. Later variations of the Canonflex called the RP and RM sold marginally better, but they offered a more basic feature set at a discount price and in no way competed with the Nikon F.

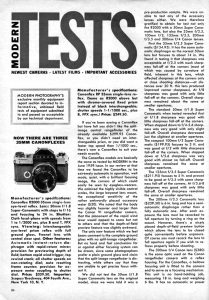

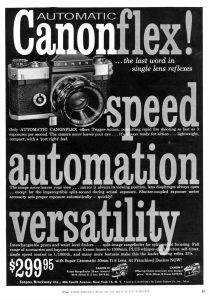

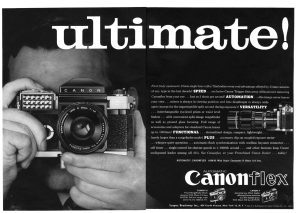

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that the Canonflex was a flop, but why? In the late 1950s, Canon was a MUCH bigger company than Nippon Kogaku, and their Leica Thread Mount rangefinder cameras sold really well, especially in Europe. Even reviews like the one on the right, originally published in the June 1959 issue of Modern Photography were generally positive of the camera. So, what happened?

In my mind, the most obvious reason is that Nippon Kogaku wisely developed both the Nikon SP rangefinder and Nikon F side by side splitting the cost and burden of an all new camera with that of an established one. Both cameras shared nearly 90% of the same parts, including most of the body and shutter. Nippon Kogaku also tremendously valued input from professional photographers. At every step of the Nikon SLR’s design, Nippon Kogaku relentlessly listened to the needs and desires of the photographers using their cameras, delivering to them exactly what they wanted. Even before the Nikon F ever went on sale, it had the benefit of being designed by professional photographers for professional photographers.

Although Nippon Kogaku would release two more rangefinder models after the release of the SP, each was a more simplified model. After the SP’s release in 1957, they went all in on their new SLR. Canon on the other hand, wanted to hold onto the rangefinder market for much longer splitting their efforts between the two designs. Canon would continue to evolve their Leica Thread Mount rangefinders until the Canon 7s in April 1965, and would continue to make fixed lens rangefinders until the Canon A35F in March 1978. Perhaps Canon’s size and market share made them wary of abandoning their successful rangefinders and going into what was still considered uncharted waters with SLRs.

Despite this, the Canonflex wasn’t a horrible camera. It was a heavy duty camera that offered many of the same features of the Nikon F like an interchangeable viewfinder allowing the use of pentaprisms, waist level, and precision viewfinders. Both cameras had self timers, flash synchronized shutters, and an instant return reflex mirror.

The Canonflex attempted to top the Nikon with a unique bottom mounted trigger film advance that claimed to offer the possibility of 3 frames per second without the use of a motor drive. The method in which the interchangeable viewfinders attached to the body was superior to that of Nikon’s design in that they slid on and off along a track. It also had a hinged film door that simplified film loading compared to the Nikon F’s rangefinder design where the entire back and bottom had to come off the camera to load film. The later Canonflex R2000 featured a redesigned shutter with a new top 1/2000 shutter speed, one faster than that of the Nikon. It also sold for less.

When first released in May 1959, the Canonflex came with a Super Canomatic R 50mm f/1.8 lens for $299.95 compared to the Nikon F which came with a slightly slower Nikkor 50mm f/2 lens for $329.50.

Despite these improvements, they didn’t add up to what professional photographers actually wanted. Nippon Kogaku on the other hand, listened to the needs of the pros and gave them things like the ability to use an electric motor drive, mirror lockup, interchangeable focusing screens, and the ability to couple the exposure meter to the aperture of the lens, all features which the Canonflex lacked. In an odd twist, one of the Canonflex’s signature features, it’s rapid wind bottom trigger film advance proved to be a huge problem as it was extremely awkward to use with the camera in portrait mode, and prevented it’s use altogether when mounted on a tripod.

Perhaps the biggest nail in the coffin to the Canonflex’s success was the miserable lens selection available upon it’s release. Where the Nikon F had the benefit of a complete selection of wide angle to telephoto lenses ranging from 21mm all the way to 135mm, Canon only had two lenses available at launch, the Super Canonmatic 50/1.8 and 100/2 lenses. For photographers who wished to shoot other focal lengths, adapters were sold to allow the use of Canon’s screw mount rangefinder lenses, but only at 85mm and longer. It wouldn’t be until a few months after the Canonflex’s introduction that any other focal lengths, including wide angle, were available.

Perhaps the biggest nail in the coffin to the Canonflex’s success was the miserable lens selection available upon it’s release. Where the Nikon F had the benefit of a complete selection of wide angle to telephoto lenses ranging from 21mm all the way to 135mm, Canon only had two lenses available at launch, the Super Canonmatic 50/1.8 and 100/2 lenses. For photographers who wished to shoot other focal lengths, adapters were sold to allow the use of Canon’s screw mount rangefinder lenses, but only at 85mm and longer. It wouldn’t be until a few months after the Canonflex’s introduction that any other focal lengths, including wide angle, were available.

Eventually there would be a range of lenses from 35mm f/2.5 to 135mm f/3.5 with automatic diaphragms, a faster 50mm f/1.2 lens, and longer lenses from 300mm f/4 to 1000mm f/11 with preset diaphragms. There was even a zoom lens, called the 55-135mm f/3.5 Zoom available, but it is incredibly rare.

The Canonflex’s lens mount proved to be problematic as well. From the start, the breech lock bayonet mount proved to be unpopular as it often required two hands and the camera resting on a table to mount and unmount the lens. Lenses with an automatic diaphragm required two mechanical pins to connect to the body. The first armed the stop-down spring, and the second activated it.

The manner in which the diaphragm worked on the Canon lenses was opposite of that used by Nippon Kogaku and their Nikkor lenses. When a Nikkor lens is removed from the camera body, the lens diaphragm defaults to it’s smallest setting. Only when attaching the lens back to the camera will it open back up via a single sliding lever. On the Canon, the diaphragm would remain wide open with the lens removed from the camera, and these pins would be required to first arm the diaphragm and later activate it.

The arming pin was activated by the film advance trigger and had the potential to cause a strange side effect where if you remove the lens from the camera without advancing the trigger, then advance the trigger with no lens (or a different lens) attached, and then reattach the first lens, the diaphragm would not become armed, and would not stop down upon firing the shutter. While this was likely not something a photographer would typically do, it is a symptom of problems that would only further harm the reputation of the camera. This complicated system was unique to original R-mount lenses for the Canonflex, and would be corrected with Canon’s later FL mount. For this reason, Canon R-mount lenses will not work correctly on later Canon bodies, and in some cases may even cause damage.

Comparing the Nikon F and Canonflex through the eyes of a professional photographer in 1959, the Canon’s lower price and reputation of coming from a larger company might have appealed to them, but when looked at as a whole, the Nikon F was superior in every way that mattered. Nippon Kogaku aimed their camera squarely at the professional photographer, and upon hitting their target, clearly set the standard to which all professional cameras needed to follow, dooming companies like Canon to forever play catch up.

None of this stopped Canon from promoting their new camera. The following is a 24 page promotional pamphlet created that championed the Canon’s design and feature set. Click the full screen button for easier viewing of PDF files.

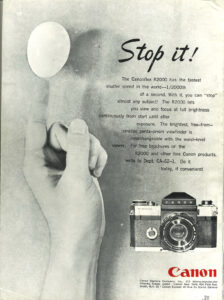

In September 1960, two new models in the Canonflex series were released. The first was an updated model called the R2000 which upped the top speed of the cloth shutter to 1/2000. This likely was in an effort to “one up” the Nikon F by offering a shutter that was one speed faster, although in terms of being first, Konica beat the R2000 to the market in February 1960 with the world’s first 1/2000 shutter in the Konica F. Strangely, despite this upgrade to the shutter, the viewing screen was changed to eliminate the split image focus aide from the original Canonflex. In it’s place was just a large round piece of ground glass, surrounded by a Fresnel pattern.

The R2000 was only produced for a very short time with an estimated 8800 ever made, making it the least common of all Canonflex models. Although originally intended to be sold in the United States, very few ever made it here, making them extremely difficult to locate outside of Japan.

The second new model was called the Canonflex RP, which was internally very similar to the original model, but replaced the interchangeable viewfinder with a fixed one, simplified the self-timer, and added the ability to connect diopters or eye cups to the rear viewfinder window. Although marketed as an amateur level camera, it was internally identical to the Canonflex and built to the same level of quality.

Realizing that the Canonflex series would never compete with the Nikon F on a professional level, in February 1962 a fourth Canonflex model called the RM would be released. It’s release coincided with Canon’s US partnership with Bell & Howell, and it is thought that it’s existence was partially due to an agreement between the two companies. Despite bearing the Canonflex name and using the same lens mount, the camera was very different from the three models that preceded it. Featuring an in-body selenium light meter and completely redesigned prism and top plate, the RM replaced the bottom trigger film advance with a more traditional top plate thumb lever and had a few other minor changes as well. The camera weighed less by about 100 grams suggesting a build quality less catered to the rigors of professional use. The Canonflex RM out sold the rest of the Canonflex series combined, due in large part to the massive distribution that Bell & Howell enjoyed in the United States. A total of 71,000 RMs were sold with a majority of them marked as Bell & Howell/Canon.

After the Canonflex’s failure, Canon would go back to the drawing board and release a new line of Canon SLRs, starting with the Canon FX in April 1964. The FX would upgrade the original Canon R-mount to support full open aperture metering, offer a more traditional top plate film advance lever, and a coupled in body CdS exposure meter. The FX would set the stage for a whole generation of successful Canon FL and FD mount SLRs that would stay in production for the next 2 decades.

In a strange twist, Canon’s failure of the Canonflex might have helped them in later years as it forced them to focus on the amateur market. This allowed them to experiment with new features such as electronic shutters and automatic focus that Nippon Kogaku was slow to adopt. Professionals, by their very definition rely on their cameras for their livelihood and require absolute dependability, something that innovative features don’t often afford. Canon would eventually release models like the Canon EF, AE-1, and A-1 that had in body automatic exposure, electronic shutters, and LED viewfinder displays that would help them succeed well into the future.

Today, the Canonflex series occupies a less than glamorous reputation among collectors. The few people who know what they are, remember them as the failed competitor to the Nikon F. They are a curious relic of the past offering a strange feature set, an unreliable lens system, and with so few ever made, aren’t exactly easy to come by. Yet if you can look past their history, these were well built cameras that if anything, deserve a look by anyone considering a late 1950s/early 1960s Japanese SLR.

My Thoughts

Prior to coming across this Canonflex, my oldest Canon SLR was the Canon EF, a camera I previously declared my favorite Canon SLR. I had seen pictures of the earlier Canon SLRs, but never thought they were interesting enough to pursue.

Then one day, while visiting a local camera repair shop, I spotted a unique looking SLR with a black pentaprism on the top shelf of a display case and I asked the lady if I could see it.

She unlocked the case and pulled out this heavily worn and ratty looking Canonflex R2000. At the time, I had no idea what the R2000 was, or that it was a pretty rare camera, but I liked the look and feel of it, and I really fell in love with it’s patina. This thing had seen HEAVY use, and showed it in nearly every tactile part of the camera, yet it worked perfectly. The shutter fired at all speeds, and all of the motions of the camera operated smoothly and worked as they should. The shop I was in was a mom and pop style shop where the “mom” ran the front of the shop, and the “pop” did the work in a back room. The lady told me that the camera had been serviced by her husband for a customer years ago, but they never picked it up and it just sat there. I continued to play with a camera and eventually asked how much. After a bit of negotiating, I walked out of there with the camera at a price I was happy with, but would later discover was an absolute steal.

The Canonflex is very solid, weighing in at nearly 1 kg with the Super Canonmatic 50mm f/1.8 lens. This is not a camera you’d want to drop on your toe. The large black prism dominates the top plate of the camera, and it’s two tone style nicely compliments the chrome body, similar to the Minolta XE-5.

Removing the viewfinder is very easy and one of the areas in which the Canonflex topped the Nikon F. To remove the viewfinder, simply press down on a small catch on the left side of the mirror box on the front of the camera and the viewfinder can be smoothly slid backwards off the camera.

On the left side of the top plate is an ordinary rewind lever, but beneath it is a clever film reminder dial that shows both speed, film type, and number of exposures. Adjusting these reminders requires lifting of the rewind lever, which reveals two small serrated levers. Since the Canonflex does not have an internal meter, these reminders are just there for reference and have no impact on the rest of the camera.

The shutter speed selector is large and has a deep knurl to the edges that make it easy to grip and gives a confident click at each stop. Unlike other cameras with clip-on meters, the Canonflex meter does not cover the shutter speed dial. Instead it connects to a small gear on the underside of the dial. Although the original Canonflex meter will connect to the R2000, it lacks the top 1/2000 shutter speed setting, so a dedicated one was also developed which includes this speed.

Beneath the shutter release is a sliding shutter lock for Timed exposures only. With the shutter speed dial in the “B-T” position, when this lock is engaged and the shutter released, the shutter will remain open for a long as this lock is engaged. To close the shutter, you must slide this lock back to it’s original position. Although it does look like a normal shutter release lock, it will not prevent the shutter from being fired at any other speed. Finally, there is the automatic resetting exposure counter which is nicely located under a glass viewing window making the numbers large and easy to see.

The back of the camera doesn’t have any controls, just the rear eye piece for the viewfinder. Notice there is no bayonet or screw ring around the perimeter of the eye piece to attach different diopters or even a rubber eye cup. This is a change that would later be made on the Canonflex RP.

Flip over the camera and the bottom plate is more cluttered than usual, especially for a SLR. This, of course, is due to the bottom trigger film advance. Early on, the Canonflex was developed using the basic design of the Canon VL rangefinder which also had a trigger film advance. Unlike the VL however, the Canonflex’s has both a hinged tip, and pivots on a rotating shaft, as opposed to a folding lever that rides on a linear track. Not everyone is a fan of bottom trigger cameras to begin with, but between the two different types, the Canonflex’s feels more natural and is more comfortable to use.

Other things on the bottom plate are the 1/4″ tripod socket, rewind button, and a rotating door lock which allows you to use Leica style reloadable cassettes inside of the camera. To open the back of the camera, simply rotate this lock and the right hinged door will pop open.

With the back open, loading film is a painless endeavor. Film transport is from left to right onto a non removable single slotted take up spool. On the underside of the door, next to the pressure plate is a metal roller which when combined with the clockwise turning take up spool, helps to reduce film curl while it’s in the camera. This not only helps maintain flatness across the film gate ensuring properly focused shots, but also can make developing the film easier since it lays flatter.

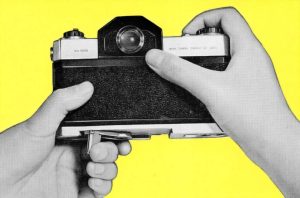

Canon R-mount lenses differ from later FL/FD mount lenses in that there are two separate rings for controlling the diaphragm (aperture) of the lens. The ring closest to the front of the lens (the top one in the image to the right) controls the f/stop that the lens will automatically stop down to when the shutter is released. The one closest to the camera body is the “visual aperture ring” which controls the diaphragm when composing through the viewfinder.

This works similarly to a depth of field button like on other SLRs in that you can turn it to the smallest number (wide open) to allow maximum light into the viewfinder for composing, or manually stop down the lens to preview depth of field while composing. In the image to the right, both rings are set to f/5.6 which means the iris is partially closed both when composing and exposing an image.

Unlike other preset lenses like the Helios-44 however, these two rings can be turned to any number regardless of the position of the other. You could preview your image through the viewfinder at f/16 while exposing an image at f/1.8 or preview your image at f/1.8 but expose it at f/16 if you want. I discussed earlier in this article the shortcomings of the complexity of these R-mount lenses, and this is just another example. The design makes no sense to me. Canon designed it to allow for composing wide open, so why not just make it a button like everyone else did? Why make two separate rings that essentially accomplish the same thing?

Removing the lens from the camera is exactly like later Canon FL/FD lenses in which you grip the knurled metal ring on the lens closest to the camera body and rotate it clockwise to release the breech lock. With the lock disengaged, the entire lens can be pulled straight off without having to twist it. Over the years, many people have complained about this breech lock system in that it’s slower and requires both hands to use. Some people don’t mind it, others hate it.

Next to the lens mount is a circular metal key that functions as the self-timer. It has a folding handle that when folded out 90 degrees to the body which looks like the knob design on some Zeiss Ikon cameras and can be rotated to activate a 10 second delay upon releasing the shutter. The self-timer cannot be cancelled once it is set.

The viewfinder of the R2000 is large and bright and easy enough to use but lacks any type of focus aide, which is strange considering the original Canonflex had a split image rangefinder and ground glass focusing aides on the viewing screen. I was unable to find any explanation for why this feature was removed on the R2000. Despite this loss however, the whole thing is quite bright and generally easy to use care of a circular Fresnel pattern which is visible in the image to the left.

Upon handling the Canonflex R2000, there’s enough to like about it to where you can tell some thought was put into it’s various features. Nothing feels cheap and with a decent amount of heft, it is clear this camera was up to the challenge of the daily rigors of professional use, but how does it actually perform with film?

My Results

I didn’t have the Canonflex R2000 for long before succumbing to my desire to use it. Shortly after getting it, I had a trip planned to visit relatives in northern Michigan, so I loaded up a roll of fresh Fuji 200 and took it with me.

Canon was not a stranger to making good lenses. Of all the things I predicted I would talk about before developing this film, I didn’t think image quality would be one, and I was right. As you might expect, the images from the Super Canomatic lens turned out great. This is a 6-element coated lens that handled colors with contrast and great accuracy. Image sharpness was great from corner to corner and there was little to no vignetting. I saw no other kinds of optical aberrations that plague lesser lenses. It was clear that if I had something to say about the Canonflex, it wouldn’t be about the images it made.

The whole experience of using the Canonflex R2000 was a mixed bag. It was difficult to not let the camera’s reputation as a failure taint my opinion of it, so I tried to keep an open mind and rather than continually comparing it to the Nikon F, I looked at like like just another vintage SLR.

I didn’t mind the lack of a interchangeable focusing screens, motor drive connection, or mirror lock up as these are all features I’m not likely to use when testing an old camera. I actually quite enjoyed the bottom mounted film advance as it reminded me of the one on the Ricoh 519M, another camera I gave very high marks to.

The camera is sturdy and feels very well made in your hands. Nothing creaked or felt loose or wobbly while using it. This particular camera shows obvious signs of heavy use, which considering the fact that it still worked perfectly, suggests that the camera’s build quality was up to the task for a professional camera.

My complaints about the camera are actually quite few. I would have preferred a better viewing screen, like that of the original model, but perhaps my biggest complaint was Canon’s idiotic design for the dual aperture rings. There simply was no reason to have a separate ring just for stopping down the lens. In use, it’s actually not that big of a deal as I left the second ring at 1.8 the entire time and picked an appropriate f/stop with the other. It’s just stupid.

In what is likely going to cause some controversy, my favorite thing about the Canonflex is that it’s not a Nikon F. For all of the great things I can say about that camera, it set the standard for what a 35mm SLR should be. Every control on the F is exactly where you expect it to be. Every function of the camera works exactly how you expect it to work. There’s nothing unique about the controls and using it is drama free. That’s great for the professional who needs to rely on his or her camera to always be ready for the next shot without having to think, but with the Canonflex, as a casual photographer who likes reviewing old cameras, I quite enjoyed the eccentricities of the camera.

Yeah, the bottom mounted trigger advance blocks the use of a tripod, and the breech lock lens mount is annoying, and of course there’s those stupid aperture rings, but it’s stuff like that and the circular self timer, the large and easy to use shutter speed dial, and the two toned viewfinder that make the camera interesting, and not just another Nikon F. My shooting experience with the Canonflex was memorable and interesting, and for that, the camera is a success, at least for me. YMMV.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://www.cameraquest.com/canonflx.htm

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Canonflex

https://basepath.com/ClassicCameras/grid.php?id=16678029&key=mhVVw6&back=article.php

https://tinkeringwithcameras.blogspot.com/2008/03/Canonflex-R2000.html

https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/cancanflexr2000.htm

https://flynngraphics.ca/the-collection/the-cameras/canonflex/

Great Review? YES! Interesting Camera? YES! Would those dual aperture rings run the risk of me accidentally setting them wrong and ruining a roll and the wanting to inflict harm on this camera? YES! As much as I struggle with preset designs, I could see where this would be a camera I could only shoot wide open. I’m sure I’d figure it out once looking through the viewfinder (or maybe I wouldn’t) but that design seems like something that only a tone deaf Engineer could dream up!

You bring up a good point. While I never had that happen to me, I could see it happening to some one. That, among other things paints a clear picture that Canon misunderstood the needs of the SLR user when designing this camera. They would later get it right with the F-1, but it would take them more than a decade later, and in my opinion, they never truly caught up with Nikon until the EOS system of 1986.

Keppler noted in passing one of the problems with trigger advances. It is impossible to focus, advance and fire the shutter without changing the position of one hand or the other. In theory one can take pictures rapidly, but not while changing focus between frames.

How does one shoot and advance while the camera is on a tripod? The Canon VT and VIT at least had a knob on top for advancing the film while the camera was on a tripod.

I note that all of the sample pictures were taken horizontally. 🙂

Congratulations to you, Mike, on 200 interesting, detailed reviews! And a thank you also for mentioning Peter Dechert, whose little red Canon rangefinder book is on my shelf between Jim McKeown’s opus and a copy of “Glass, Brass and Chrome”.

Mike, a fascinating read. As you know, I drooled over this camera as a teenager when I read the photographic press of the time. I never did get to own one, having gone down the TLR route with my YashicaMat. My first slr would have to wait until 1967 and this does link to a comment you made in your review.

You mentioned that Canon had put a toe in the slr waters with two lenses with Exakta bayonet mount. Actually, there is a third Canon lens with the Exakta mount, albeit this is incompatible with Exakta cameras and which is due to the semi-auto diaphragm triggering mechanism. The lens comes after the era of the two you mention and is specific to the Mamiya Prismat NP rebadging for the “Reflexa” camera. It is my understanding that the Reflexa + Canon OM f1.9/50mm combination was primarily intended for the UK market where the Exakta was making a name as the slr at a time before the Japanese onslaught. But I do find it odd that Canon could be persuaded to do a one-off Exakta mount lens that wasn’t compatible with Exakta bodies.

You touch upon the fact that the focusing aids were removed to leave a plain screen. There is a possible reason for this decision, but is entirely conjecture on my part. These focusing “aids” become useless from around f5.6 and smaller, and can be dependent upon focal length, such that they are more of a hindrance to viewing the centre part of the screen. Thinking in terms of the range of focal lengths envisaged, perhaps Canon thought that the plain screen would be more universal in operation.

With that chunk of a penta-prism housing in black, I still think the Canon looks better than the Nikon F. But having read your comments about the idiosyncratic lens, I’m not sure that when considering an slr in 1967 I would have considered the Canon if I’d come across one. Dreams and fantasies are probably best left that way.

Yes, I am familiar with the Canon OM lenses for the Mamiya Prismat. Peter Dechert talks about it briefly in his SLR book. The initials “OM” that Canon used on that lens refer to “Osawa/Mamiya”, with Osawa being an exporter that both Canon and Mamiya used. Osawa was Bell & Howell’s Japanese division, which was why Canon used them as they had a partnership with Bell & Howell in the United States. The Prismat NP had three Mamiya lenses available for it, with the Canon lens the “top dog” lens. The combination was not popular and very few were sold, which means that they are very hard to come by today and very collectible.

Interestingly, Canon’s OM lens for the Prismat was not their only dealings with Mamiya as in 1963, both Mamiya and Canon each released nearly identical leaf shutter SLRs called the Mamiya Auto-Lux and Canon Canonex. There is much debate as to whether Canon or Mamiya made either model. Canon’s own website doesn’t mention Mamiya at all, but it’s more plausible that Mamiya, a company with experience building leaf shutter SLRs would have made both and simply rebranded one for Canon, than Canon went out of its way to design from the ground up, an all new leaf shutter SLR (of which they had no experience with leaf shutters, and their only SLR at that time was the Canonflex series which wasn’t very successful), only to discontinue it 6 months after it’s release.

And finally, on the borderline of bizarre, although Mamiya and Canon seemed to have this partnership in the early 60s, Mamiya also built the Nikkorex leaf shutter SLRs for Nippon Kogaku, Canon’s biggest rival. As you probably know, early Nikkorexes are leaf shutter SLRs like the Prismat and Auto-Lux, but the later Nikkorex F used a Copal Square focal plane shutter. The Nikkorex F was a mild success, but was only produced for a short time as well. After Nippon Kogaku stopped ordering them from Mamiya, they sold the design to Riken, and the camera was later produced, nearly unchanged, as the Ricoh Singlex.

So that concludes the bizarre early 1960s Canon/Mamiya/Nikon/Riken love triangle!

Very interesting. Thanks, Mike. I wonder where Kowa may fit into the above mix, if at all? Also noted for a range of fixed lens leaf shutter slrs. I’ve got two well used but fully serviceable models, the “E” and “H”. V/F’s are surprisingly bright.

Hey man no offense but your pictures suck. Holy hell they’re lame. Give this camera to someone with some talent PLEASE.

I agree. Send me your address! 🙂

About those two aperture rings, what exactly happens if I put DOF ring to f16, and preset aperture ring to f1.8, like you wrote in review? When shutter button is pressed, aperture automatically opens up to f1.8, and then closes to f16 again? DOF ring can not be used to control aperture during exposure?