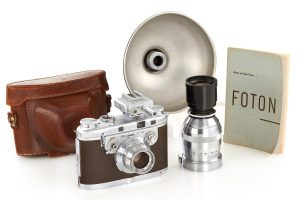

This is a Bell & Howell Foton, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Bell & Howell Company of Chicago, Illinois. It first went on sale in 1948 as a top of the line American built camera, designed to compete with the best of what Germany had to offer. The camera featured a clockwork motorized film transport that can continuously shoot up to 4 exposures per second. It had an interchangeable lens mount and came standard with a 2 Inch f/2 Cooke Amotal Anastigmat lens, designed and built by Taylor, Tayor, & Hobson of England. When it first went on sale, the camera sold for $700 which was an astronomical amount at the time, and while the camera performed very well and proved to be quite reliable, sold poorly and quickly disappeared from the market.

This is a Bell & Howell Foton, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Bell & Howell Company of Chicago, Illinois. It first went on sale in 1948 as a top of the line American built camera, designed to compete with the best of what Germany had to offer. The camera featured a clockwork motorized film transport that can continuously shoot up to 4 exposures per second. It had an interchangeable lens mount and came standard with a 2 Inch f/2 Cooke Amotal Anastigmat lens, designed and built by Taylor, Tayor, & Hobson of England. When it first went on sale, the camera sold for $700 which was an astronomical amount at the time, and while the camera performed very well and proved to be quite reliable, sold poorly and quickly disappeared from the market.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 2 Inch (~50mm) f/2 T-2.2 Cooke Amotal Anastigmat coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Foton Screw (~34mm) for 2 Inch lenses and External Bayonet for 4 Inch and Above

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Viewfinder and Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Bell & Howell Vertically Traveling Metal Blade Shutter

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe and Full M and X Flash Sync at All Speeds

Weight: 906 grams (w/ lens), 804 (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/bell_howell_foton.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Bell & Howell Foton was a top of the line, innovative, and very expensive camera upon it’s release in 1948. It offered some features that weren’t available in any other camera at the time. It came from a company that was an industry leader in the motion picture industry, but a relative newcomer to the still photography market. The Foton is one of the rarest cameras I’ve ever had the pleasure shooting, but in addition to it’s rarity, it’s also one of the prettiest, and most fun cameras I’ve ever used. This is not a camera that the average collector will have the opportunity to see often, but if you do, I absolutely recommend doing everything you can to try and get your hands on it as there truly has never been another camera ever made, quite like it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for innovation and excellence, the complete package, +1 for it’s many historical firsts | ||||||

| Final Score | 16.3 | ||||||

History

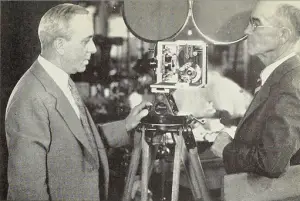

The Bell & Howell Company was incorporated on February 17, 1907 by Donald J. Bell and Albert S. Howell as a maker of cinematic film projectors and cameras. They were originally based out of Wheeling, Illinois which is a far northwest suburb of Chicago.

Prior to the company’s existence, Donald Bell was an accomplished mechanic and projectionist and had worked in the cinema industry since at least the 1890s. Albert Howell was ten years younger than Bell and by the late 1890s, had been working toward a degree in mechanical engineering from the Armour Institute of Technology in Chicago (would later become the Illinois Institute of Technology) while serving an apprenticeship at several local area machine shops.

How Bell and Howell first met and came to work together is not completely clear as there are conflicting versions of the story which are explained in a blog post by the Made in Chicago Museum. The one that seems most likely comes from a 1933 interview with Donald Bell where he said that he employed the younger Howell between the spring of 1905 and summer of 1906 to help him refine an earlier projector called the Kinodrome which Bell had built for filmmaker George K. Spoor. Bell had claimed to be impressed with Howell’s inventive ingenuity and their partnership worked well as Bell & Howell officially came into existence the very next February.

In the company’s early years, Donald Bell served as chairman and lead sales person, Howell was the chief designer, coming up with new and exciting innovations in the motion picture industry. In addition to his various contributions to projector and camera design, Albert Howell also strove to standardize the film cinema industry. Prior to the first decade of the 20th century, things like frame size, spacing, and speed were inconsistent across various manufacturers of cameras and projectors. Movies shot on one type of camera and film were often incompatible with projectors designed for other standards and vice versa. This limited which movies could be shown in a particular theater as if a movie was shot using a different standard, it wouldn’t play on a theater’s equipment. Each manufacturer would have their own ideas of how motion picture film should work, and Howell, along with other inventors like Thomas Edison worked towards a unified standard.

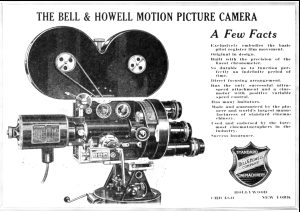

In their early years, Bell & Howell was just one of many companies making motion picture cameras and projectors, and while their voice was no louder than others, the quality of their products was so good, that over the next decade Bell & Howell would become an industry leader, and their choice of 35mm film became the standard to which the entire industry would eventually move toward. While they can’t claim that they invented 35mm cinema film, it was their success at it that allowed it to succeed in the motion picture, and later still film industries. As a result, we can credit the widespread use of 35mm film in film cameras, and its later influence on the size of electronic sensors in digital cameras, to Bell & Howell.

Bell & Howell’s first big success came in 1912 with their Model 2709 motion picture camera. The 2709 was the world’s first all-metal commercially available 35mm motion picture camera. It dominated Hollywood motion picture studios and was so popular, it remained in production until 1958. Filmmaker Charlie Chaplin exclusively used Bell & Howell products along with many other Hollywood filmmakers. If you’ve ever seen an early 20th century motion picture, there is a very good chance it was filmed on a Bell & Howell camera.

Bell & Howell’s massive success came at a cost, as it proved to be the catalyst for Donald Bell’s exit from the company. Although based in Chicago, Bell was often traveling back and forth to Hollywood and other areas of the country to help spread word of the company’s products. This meant that he wasn’t around for a large amount of the company’s creative and administrative decisions back home, and Bell developed a bit of paranoia of how Howell, and another man named Joseph H. McNabb were running the company.

In 1917, Donald Bell would attempt to regain control of the company by firing both Howell and McNabb, but in a strange twist, Howell and McNabb countered their termination and came up with a plan to buy out Bell’s share of the company for $200,000 (about $4 million today) to which Bell accepted.

Despite this change, Bell & Howell’s success continued with expanding product lines in 16mm and other amateur film sizes, but it was the onset of World War II where the company saw it’s greatest success. As a respected American company, Bell & Howell received numerous grants from the US government to produce a large variety of military use products, including war time cameras use for everything from filming battles to calibrating gun sights. In order to meet demand, Bell & Howell opened up a new factory in 1943 that employed at least 3000 employees, many of which were women and minorities since many of the company’s original workers had enlisted in the military.

The company’s massive success came to a screeching halt in 1945 as the war ended and nearly all of the government’s demand had disappeared. Faced with an excess of staff and capacity, the company began laying off workers and trying to return to mostly civilian use products. Making matters worse, a large number of competing American and foreign companies from Japan and Europe entered the marketplace, further reducing demand.

But it was a change in leadership at the company that had the biggest impact. After Donald Bell’s exit from the company in 1917, Bell & Howell enjoyed consistent leadership for over 30 years until company president Joseph McNabb’s death in 1949. Although Albert Howell would take over as President, he too, would pass away only two years later in 1951. It was around this time that in 1948, Bell & Howell would release one of it’s most innovative and interesting products, the Foton camera.

How and why Bell & Howell, a company almost entirely based in the motion picture industry decided to not only design and build an all new still picture camera, but to design one with such lofty features and a high price is largely a mystery. In my research for this article, I was unable to find a whole lot of conclusive information about the camera’s development.

The Foton’s user manual states that the camera was the result of “ten years of painstaking research” which suggests it’s development started around 1938. But who started it? Was this a direction the company wanted to go right before the war, or was the Foton the result of multiple different projects that culminated into a still photographic camera?

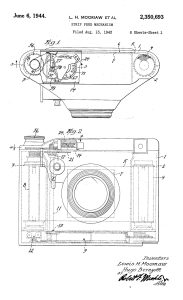

One of the best clues about the origin of the Foton can be found on Scott’s Photographica Collection, where he says that two US patents filed by a man named Lewis H. Moomaw in 1935 and 1938 for a high speed camera shutter may have been the foundation for the Foton’s shutter. While digging through the Google Patent Search, I found a third patent that I also think is relevant.

- US Patent 2,082,274 – This is the earliest patent with Moomaw’s name for anything resembling what would become the Foton. It was filed on May 16, 1935 and issued on June 1, 1937 for a high speed camera shutter that looks nothing like the Foton. It makes sense that a patent this early would look nothing like a finished product, and I lack the technical expertise to understand whether or not this has anything at all to do with the Foton. Further adding to the confusion, is that according to the patent’s documentation, the patent was filed by the Folmer Graflex Corporation.

-

US Patent # 2,350,693 shows the first hint of the eventual shape of the Foton. US Patent 2,222,041 – Another patent filed by Moomaw for a photographic camera shutter on December 8, 1938 and issued on November 19, 1940. This patent is attributed solely to Moomaw, and not Folmer Graflex suggesting he was working on his own at the time. Like the previous patent, nothing in the illustration resembles the Foton, at least not that I could see.

- US Patent 2,350,693 – This patent, which I found on my own, seems to be the most conclusive link between Moomaw’s shutter and Bell & Howell’s Foton, as it was filed on August 13, 1943 by both Lewis Moomaw and another man named Hugo Bernzott on behalf of the Bell & Howell Corporation, which suggests that by 1943, Moomaw and Bell & Howell had a working relationship. Even more interesting is that a drawing on the first page with a camera body that loosely resembles the shape of the Foton. The camera illustrated has both a top heavy design and some kind of circular shutter control device in the exact position of the Foton’s shutter release button.

I found a few other patents filed after 1943 with both Moomaw and Bell & Howell mentioned which confirms that the two had a working relationship on at least part of the camera. Does that mean he only designed the shutter and not the rest of the camera, or did he take on that too? What role did the Folmer Graflex Company have in this? We’ll likely never know the answers to these questions, but at the very least, we can say with confidence that Lewis Moomaw is the man most responsible for what would become the Foton.

While we don’t have a complete picture of the Foton’s development, it’s clear that a great deal of it’s development was done during war time and that whoever was in charge of the camera’s styling, clearly took a lot of cues from the Zeiss-Ikon Contax rangefinder. I’ll discuss the various similarities between the Foton and Contax later in this review.

During the Foton’s development, Kodak had already released their Ektra camera, which at the time of it’s release in 1941 was the most advanced American 35mm camera ever made, and topped the features of the best German cameras. Perhaps Bell & Howell wanted a flagship camera of their own to compete with Kodak. Perhaps as part of one of Bell & Howell’s many US military contracts, a need was established for a high spec American made 35mm camera to fill the void of German models in the years after the war.

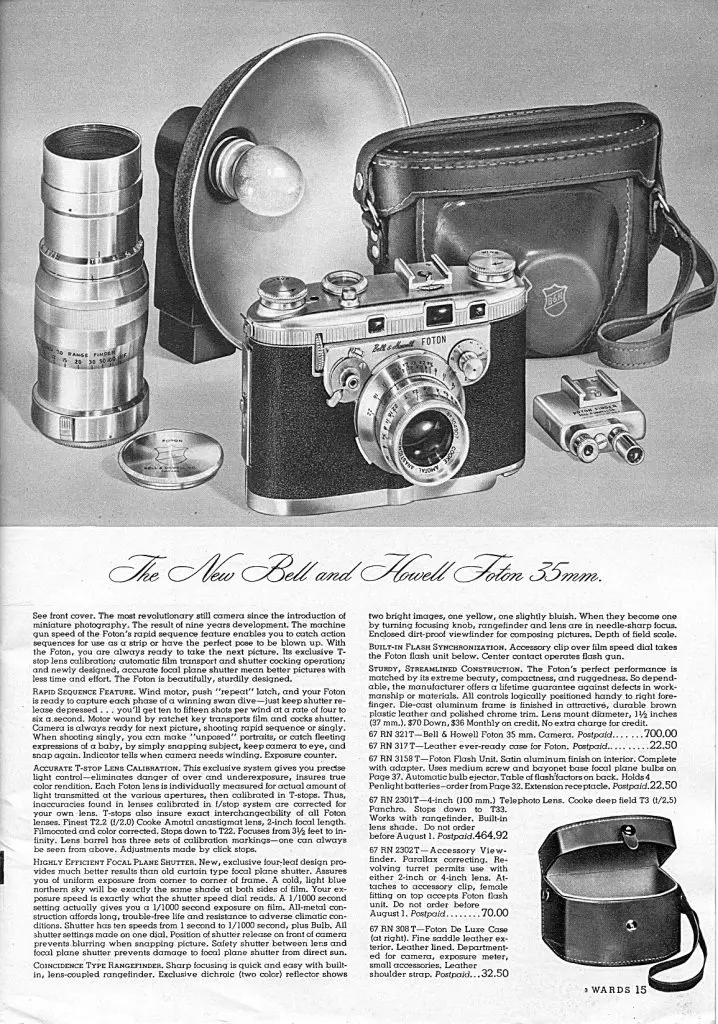

When the Foton finally went on sale in 1948, it had a list price of $700, which is the highest price of any camera I’ve ever seen from the era. The optional 4 inch (100mm) telephoto lens was $464.92, a price that is more expensive than nearly every other camera made at the time. Heck, even the 4 inch lens’s accessory viewfinder was $70! Each of these prices compare to $7500, $5000, and $750 today making this camera more expensive than even the most top of the line digital cameras today.

The Chicago based department store chain Montgomery Ward dedicated the cover and an entire page of it’s 1949 Photographic Catalog to the Foton.

The Foton’s $700 price tag did not last long, as it was quickly dropped to a still hard to swallow price of $498 ($5300 today). According to an article in the May 1975 issue of Modern Photography, Charlie Pelish of New York’s Fotoshop suggests that the camera sold worse after the price drop:

I remember when they first hit the market in the 40’s. At the price, they were steady sellers, I sold one or two a month. But then Bell & Howell decided they weren’t selling fast enough and dropped the price to $498. When they did that, people lost confidence in it.

It seems as though Bell & Howell’s primary focus when creating the camera was it’s shutter and clockwork motorized film advance, rather than making it a true “system camera”. There was no provision for a removable back or the ability to load in bulk film whcih seems a bit strange as both the company’s experience making cinema cameras and the Foton’s ability to rapidly shoot multiple images per second would have greatly benefited from a 250 exposure (or larger) film supply.

Perhaps even more disappointing was the lens selection for the Foton at launch, which amounted to only the 2 inch (50mm) T-2.2 Cooke Amotal and a 4 inch (100mm) T-4 Panchrotal. McKeown’s 12th edition claims that a 12-inch Cooke lens was later available, as was a 216mm Cooke Telekinic Anastigmat lens which sold at auction in 2015. The article to the left, from the October 3, 1948 issue of the New York Times suggests that a wide angle 35mm T3.5 lens would also be available, but has never been referenced anywhere else.

Another feature of the camera was that Bell & Howell bestowed it with a Lifetime Guarantee that covered parts and labor for defects in workmanship or material. An included warranty card that came with every Foton further added that the camera was properly lubricated for one year at a time and needed to be returned to an authorized Bell & Howell dealer annually to continue the lifetime guarantee, however.

Below is a gallery of a couple advertisements for the Foton, along with a 4 page pamphlet published by Bell & Howell and sent to dealers, promoting it’s features.

When it was released, Bell & Howell was certain the Foton would be a success. In the October 4, 1948 issue of TIME magazine, an unnamed Bell & Howell employee was quoted as saying:

Bell & Howell, which has found that ‘families of both low and high incomes now spend over $550’ for movie equipment, hopes to sell 20,000 Fotons a year.

Clearly, that did not happen and the Foton disappeared from advertisements before the end of 1949 suggesting that too few were sold for Bell & Howell to continue production. It is commonly said that a majority of Fotons were sold to LIFE magazine reporters, and sports photographers who could most benefit from the high speed clockwork shutter.

There has never been any sort of official number of Fotons produced, and the serial numbers aren’t much help either as examples have been seen with a wide range of prefixes. Perhaps the best estimate is by Stephen Gandy at his Cameraquest site where he says that it is commonly believed that 2500 Kodak Ektras were ever made, and the number of Ektras to Fotons that come up to sale is about six to one, so that suggests that fewer than 500 ever made it out the door. Whether the actual number is higher or lower than 500 is anyone’s guess, but we’ll likely never know the true number.

Bell & Howell would never again make an ambitious camera like the Foton, but would put their name on various inexpensive miniature format cameras like the Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127. In 1954, they would purchase the Three Dimension Company and release a series of TDC Stereo cameras like the TDC Stereo Vivid, and in the 1960s would enter into an agreement with Canon to put their name on a variety of Canon rangefinders and SLRs exported to the United States.

Today, the Bell & Howell Foton is one of the most sought after cameras by collectors worldwide. It’s gorgeous looks, unique feature set, and extreme rarity mean they are rarely found for under $1000 with good working examples fetching far more.

When Todd Gustavson, the curator of technology for the George Eastman House wrote his book, 500 Cameras: 170 Years of Photographic Innovation, he chose the Foton for the cover over any of the other 8000 cameras in the Eastman collection.

Although out of the price ranges of most collectors, the Bell & Howell Foton is a truly special camera that deserves to be noticed. If you have an opportunity to pick one up, or in my case borrow one, I strongly encourage it!

T-Stops vs f/stops

The Cooke Amotal Anastigmat lens that came standard on the Bell & Howell Foton introduced the concept of T-stops to the world of still photography in an effort to improve upon the existing use of f/stops.

The f/stop system was created in the late 1800s as a way of standardizing the light gathering properties of lenses, and eventually replaced a confusing number of conflicting systems like the Universal Standard or US system, which was accepted by the Photographic Society of Great Britain in the 1880s.

Around 1920, the f/stop, or f/x system became the most common standard among lens makers world wide for measuring the light gathering ability of a lens. An f/stop is a simple calculation of the lens’s focal length divided by the diameter of the widest opening of the entrance pupil (usually where the diaphragm is). For a 50mm lens to have an f/stop of f/2, it must have a maximum opening of 25mm. When lenses are “stopped down”, the iris closes reducing the diameter of the opening, thus raising the f/stop number.

The f/stop system is still in use today and has become the standard for light measurement properties of still camera lenses for over a century.

Where the f/stop system fails is that it is merely a formula calculated from physical properties of a lens and has nothing to do with the actual amount of light transmitted through the lens. No photographic lens ever made passes 100% of the light that enters it through to the other side. Losses due to absorption of light and reflection of the internal glass elements cause the transmitted amount of light to always be less than 100%. The quality of the glass used to construct the lens, the number of glass elements, and the quality of the lens coatings on each element all have an impact on how much light makes it through the lens. Coated lenses do a better job of transmitting light than uncoated lenses and the number of glass elements within a lens also has an impact.

You could take two lenses, both with a measured f/stop of f/2 and if one has six uncoated elements, and the other has four coated elements, the difference in transmitted light would be significant even though they are both f/2 lenses.

This is a bigger issue for motion picture cameras as it was typical for a filmmaker to use different lenses throughout filming of movies, and as different lenses transmit different types of light, the exposure of the film would change. When shooting a single frame of film using a still camera, changes in exposure can be easily compensated while shooting or developing. Cinema film however has hundreds or even thousands of individual frames and is often shot at different times on different days with variances in lighting, and getting consistent exposure is significantly more difficult than with still photography, so there needed to be a way to come up with a standard that took into account the measured amount of light transmitted through a lens.

Enter the T-stop system which attempts to solve this problem by taking actual measurements of transmitted light through a lens. A given T-stop number is a true measurement of the actual performance of that lens, taking into account the quality of glass, number of elements, and lens coatings used in it’s construction. Like the f/stop system, T-stops are still used today in cinematography.

With Bell & Howell’s background in cinema cameras, it attempted to apply the T-stop system to a still camera, and rated the Cooke lens at T-2.2 which had it caught on with other still camera lenses, would have allowed for a true “apples to apples” comparison between different lenses of different types.

Bell & Howell was optimistic about it’s adoption and heavily promoted the superiority of the T-stop system, and in October 1948, Popular Photography ran an article promoting the benefits of the T-stop system. The article was also optimistic as it suggested new T-stop lenses would soon enter the market, which we now know never happened. To my knowledge, the Foton is the only still camera ever made that attempted to use the T-stop system. Reasons for it’s lack of acceptance was likely that in order to calculate a T-stop number, a lens had to go through the additional time and expense to have it measured, and the demand was simply not there.

My Thoughts

I’ve often used the term “unobtanium” in many of my reviews as a metaphor for those cameras of which I’ll likely never get a chance to shoot as their prices are often way out of my league. Despite the wealth of information on this site, my budget for used cameras rarely exceeds $50, and often times is much less than that. I’ve gotten many of my best deals by buying large lots of cameras, and selling off most of it just to keep one or two that I want at a price I can live with.

I’ve been incredibly lucky over the past few years to have the opportunity to borrow cameras like the Leica M3, Nikon SP, and Voigtländer Prominent from my readers that I otherwise wouldn’t have ever bought myself as they’re so far out of my typical price range. But this review isn’t about a Leica, Nikon, or Voigtländer rangefinder, its about a different kind of unobtanium camera. A camera so expensive, and so rare, that even if you do somehow manage to come across one, the odds of it working correctly are slim, and the chances of anyone loaning it out even slimmer.

The unobtanium to the unobtanium camera I speak of is the Bell & Howell Foton. A camera that first went on sale at a price of $700 in 1948 which compares to nearly $7500 today, and one that only about 500 were ever made. The Foton represents nearly everything that makes an old camera desirable, it’s rare, it has a unique feature set, it’s very attractive and distinct looking, and it works really, really well.

The source of this Foton is a reader of my site named Roy Morgenweck, who one day contacted me and offered to send me his Foton for review. Not willing to risk a chance that he wasn’t serious, I immediately responded saying sure! After a few back and forth emails, Ray packaged up his Foton and one more camera which I’ll review later this year, and sent them off to me.

After receiving the camera and unwrapping it from his box, I took it out and….HOLY COW THIS CAMERA IS BIG! The Foton is a large camera! Take a look at the image to the right where I have it placed next to a Canon IVSb and Argus C3 and you can see that it is considerably taller, and although this image doesn’t show it, the camera is quite a bit thicker too.

The camera weighs 906 grams (2 lbs) with the Cooke lens attached and 804 grams body only, making it quite the heavyweight. This weight is nearly identical to that of a Nikon F w/ Standard Prism and Nikkor 50/2 lens at 903 grams, which is impressive considering most SLRs generally are heavier than rangefinders as they have the additional weight of a mirror box, reflex mirror, and large pentaprism with focusing screen to add to their heft.

The Foton’s design is gorgeous, reminiscent of Airstream trailers and Streamline locomotives that were both very popular in the 1940s. The curved top plate is surrounded by short vertical “ribs” that encircle the front of the camera. Every surface of the camera is chrome plated metal, with exquisitely detailed knobs with deep textures at all the key tactile points. The body covering is some type of brown synthetic leather. It’s not quite as grippy as real leather, but seems to age really well as this example had no scratches, scuffs, Zeiss bumps, or any other faults found on lesser camera bodies.

Looking down upon the top plate of the Foton, we see from left to right, the rewind knob, flash hot shoe with a film speed reminder disc beneath it, the exposure counter, rewind button, shutter readiness indicator, and film take up knob.

The Foton was not the first American camera to have a hot shoe as the Univex Mercury CC from 1938 and Argus Argoflex EF which came out right before the Foton also had them. What is unique about the one in the Foton however, is that it is compatible with modern flashes, whereas the ones on the Mercury and Argus require proprietary flashguns designed for those specific cameras.

The exposure counter is additive and needs to be manually reset to zero after loading a new roll of film. The small hole to the left of the take up knob is a little window which shows a white circle whenever the shutter is cocked. If no circle appears in this window, there is not sufficient tension on the motorized film transport to cock the shutter.

The bottom of the Foton is functionally mundane with only the 1/4″ tripod socket and clockwork wind key present, but continues the “ribbed” look of the top plate with a horizontal pattern. It’s worth noting that very early Fotons lacked the ribbed pattern and had a completely smooth bottom.

Around back, the brown synthetic body covering encompasses the entire rear door, with a narrow strip along the bottom part of the body.

Near the upper left corner are two eye pieces, the smaller one on the left is for the coincident image rangefinder, and the larger one for the main viewfinder. This dual arrangement of a separate rangefinder and viewfinder allows for the rangefinder to have a greater magnification ratio like the Leica II and III for increased accuracy, as opposed to cameras in which both windows are combined.

On the camera’s side is a latch for releasing the left hinged film door for gaining access to the film compartment. Simply press down on the latch and it opens.

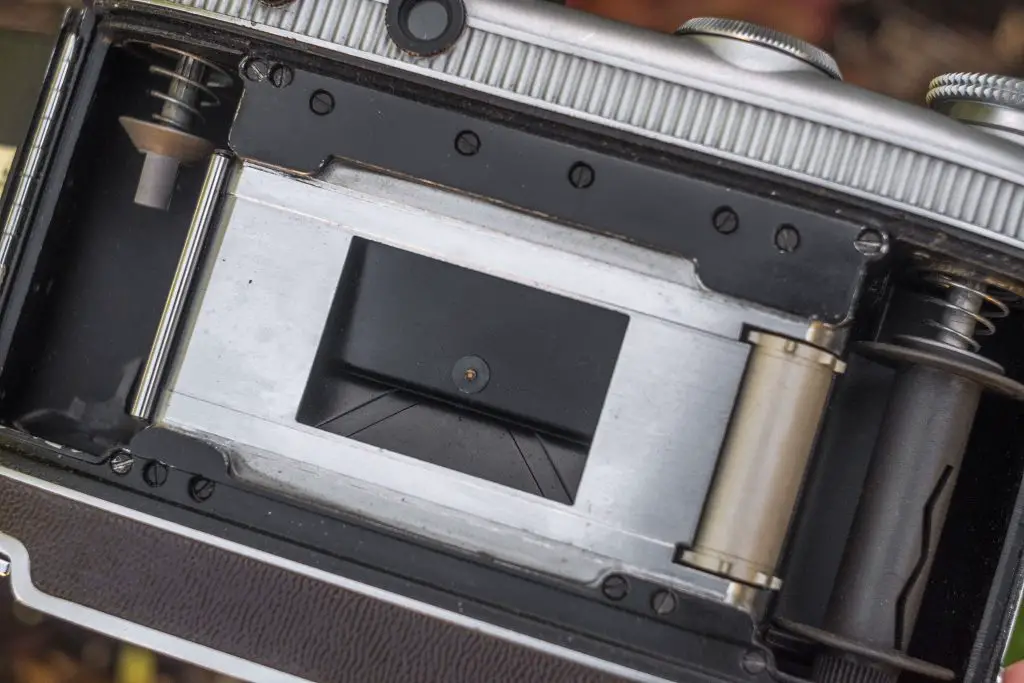

Film travels from left to right onto a fixed take up spool. The take up spool has a large vertical slot for sliding the film leader into, and a zig zag pattern on the opposite side for gripping the film. It’s actually a really effective (and fast) way of attaching a leader to the spool that I wish other cameras had. Both the film pressure plate and the film gate are unpainted polished metal, which was thought to offer less resistance to film as it traveled through the camera.

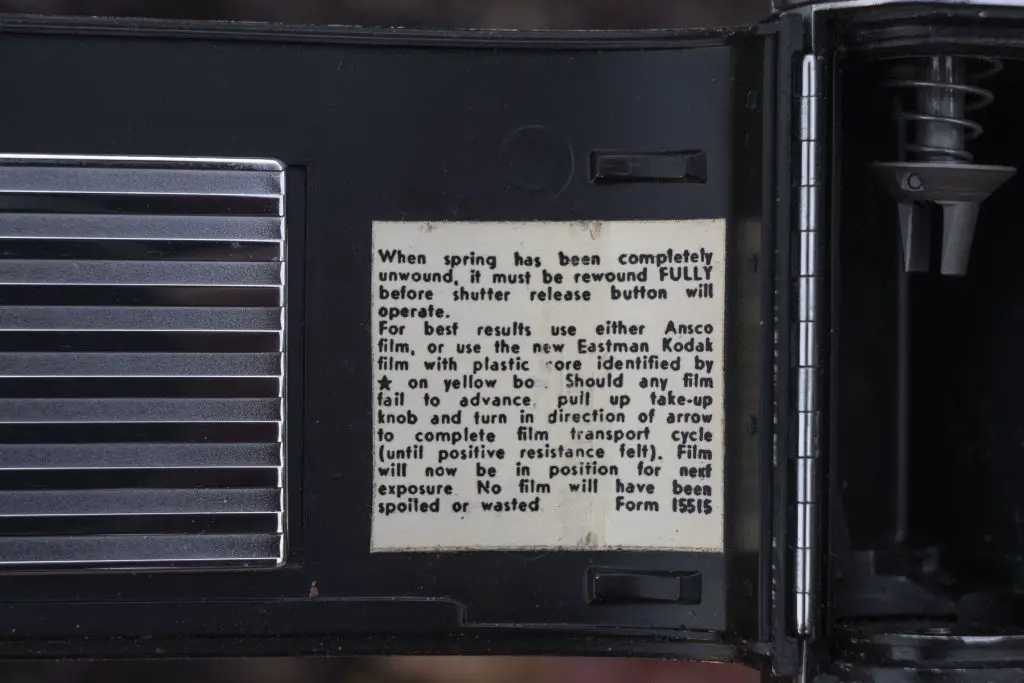

On the inside door of the film compartment is a little sticker with a reminder that you must wind up the camera fully before the shutter button will operate, a recommendation for which films to use, and instructions on what to do in the event the shutter loses tension with film in the camera.

You’ll also notice that the back of the shutter looks unlike any other you’ve likely seen, which is because it is. The Foton’s shutter is not cloth, nor does it travel horizontally, rather it travels vertically in two pieces, kind of like a Copal Square vertically traveling shutter allowing for second “curtain” to begin closing before the first curtain finishes opening. This not only allows for the Foton to achieve it’s top 1/1000 shutter speed, but the design turned out to be extremely reliable and completely immune from pinhole light leaks. As a result, many Fotons are found today with functioning shutters.

Loading film into the Foton is a rather unique affair, and something that the camera’s owner strongly advised I familiarize myself with in the user’s manual before attempting. I had planned on typing up step by step instructions for how it’s done, but I made a video instead. Even if you have no interest in loading film into this camera, it’s worth watching the video to hear the sound of the shutter firing!

NOTE: During the video below, I made a mistake around the 2:20 point where I push down on the rewind button for loading film. I was supposed to keep that button held down throughout the whole duration of advancing the film to allow for the geared shaft to rotate. It still works without doing this step, but you can see the film skipping over the sprockets which is not ideal. I would have re-shot this to video show a completely correct film loading sequence, but I had already sent the camera back well before composing this review.

In a post on rangefinderforum from February 2019, a tip was offered by Christopher Chen for loading the film which is to leave the rewind knob (not the take up knob) in the up position for the first couple of exposures after loading in a new roll of film. This will cause that knob to rotate with each press of the shutter release, similar to a normal rewind knob on most 35mm cameras which lets you see that the film is traveling correctly. Once you’ve confirmed that there are no problems with film transport, you can push in the rewind knob into it’s down position and it will stop spinning.

As seen in the video, the threaded shutter release and shutter lock are located on the front of the camera, near the 10 o’clock position around the lens mount. Pressing the shutter release with a properly wound up camera both fires the shutter and advances the film to the next exposure, simultaneously cocking the shutter for the next shot. While clockwork cameras are not new to me, the sound of this whole process is very loud. You can hear the sound of everything happening in the film loading video I made above, and while the sound doesn’t bother me, this is definitely not a camera you’d want to use in discreet situations where a silent shutter is beneficial!

Since the Foton uses a clockwork design that always sets the shutter for the next shot, you’ll want to use the shutter lock to disable the button when the camera is not in use, to prevent accidental exposures. This is done with the little handle to the bottom left of the shutter release.

Above the shutter release is a little horizontal bar that activates continuous shutter mode. Like modern film and digital cameras with motorized film transports, the Foton can be operated in single or continuous mode. In most cases, the camera should be kept in single mode, with the horizontal bar in the down position as seen in the previous image. If however, you want to shoot continuous shots, you need to lift up on this bar to reveal the word “Repeat”. With the camera set like this, pressing the shutter will continuously fire the shutter up to 4 exposures per second for as long as you keep the button pressed, or the clockwork mechanism winds out. Early documentation for the Foton suggests that it was capable of up to 6 exposures per second, but I strongly doubt this was ever possible. This continuous shutter mode was likely the most sought after feature of the camera for professional sports and fast action photographers.

To the left of the shutter release button is a vertical wheel which is used for precise focus of the lens and is easily located with the photographers right index finger, similar to that of Contax rangefinder. This wheel is optional however, as the lens may be focused by turning it, like on any other camera.

The lens itself is very compact, owing to the camera’s internal helix mount which is also similar to that of the Contax rangefinder, allowing for Foton lenses to be very compact. The lens iris on the lens is measured in T-stops, rather than f/stops like on pretty much every other lens. The merits of the T-stop system over f/stops was discussed earlier in this article.

Shutter speeds are changed via the knob on the front of the camera near the 2 o’clock position around the lens mount. Once again, like the Contax rangefinder, all speeds are contained on a single dial, without the use of a separate slow speed governor like on other cameras of the era. To change speeds, you pull the center knob outward and rotate it to your chosen speed. Speeds can be changed at any time, regardless if the shutter is set or not.

The Foton uses a simple screw lens mount for the standard 2 inch lens, so removing the lens requires no complicated process of unlocking the lens or dealing with bayonets when putting it back on. Simply rotate counterclockwise to remove, and clockwise to put it back on. I did not have access to any of the other accessory lenses for the Foton, but they use the external bayonet around the perimeter of the lens mount. This is yet another similarity with the Contax rangefinder which also uses an external bayonet for longer lenses. I did not have access to any of the Foton’s other lenses, but the manual makes mention that the telephoto lenses do not completely couple with the rangefinder.

The Foton has separate windows for the viewfinder and rangefinder like the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and Leica II/III cameras, in which the rangefinder window is a coincident image separate from the main viewfinder. In the years since these cameras were made, some collectors have the opinion that cameras in which the rangefinder is a separate window from the viewfinder window are automatically inferior.

While yes, having a combined coincident image does have it’s advantages, they’re not automatically better. For one, by having a separate rangefinder, it is not dependent on the magnification ratio of the main viewfinder which means that the rangefinder can magnify the image separately, making precise focus easier. In addition to this, all coincident image rangefinders rely on something called a beamsplitter, which is either a mirror or prism surface that allows some light to pass through it while simultaneously reflecting some light to the second rangefinder window. In doing this, some of the light from the main viewfinder window is reflected, therefore darkening the image. Cameras like the Foton with separate windows keep the beamsplitter out of the primary viewfinder window, which means that nearly 100% of all available light passes through the viewfinder, making them brighter and easier to see in lower light.

The Foton’s rangefinder patch is quite large and has a yellowish tint over a blue background. Because the rangefinder is a separate window from the viewfinder, the rangefinder patch can be larger, allowing for easier focus measurement. On the example I had for this review, the rangefinder was very cloudy and difficult to see through however, so I did not capture an image of it.

Handling the Foton is quite a pleasant experience. While a refresher of the manual before using it is a good idea, the camera has the right blend of quirks that make it interesting, while not making it a confusing ergonomic mess. It’s combination of a gorgeous design, interesting features, and mostly logical control positions makes this a really fun camera to use. But what kinds of images does it make?

My Results

With the Foton on a short term loan, I knew my time with it wouldn’t allow me to dilly dally with a bunch of different film stocks. For the first roll, I shot a 36 exposure roll of Fuji 200, and for my second roll, another 36 exposure roll, this time of Kodak TMax 100 which you can see me load in the film loading video above.

A quick note about the images below, for reasons that I still don’t understand and don’t at all blame on the camera, the black and white images from the roll of TMax 100 deteriorated somehow showing a “solarized” effect. Most of the roll was unusable, but I took the best images and included them below. I attribute this to the expired nature of the film, but despite these flaws, you can still make out the rendering and sharpness in the images.

After developing the film shot in the Foton, I could have gotten an entire strip of completely unusable blown out, or black images and I still would have been happy as handling and shooting the Foton was a pleasure, but of course that’s not what happened. Upon looking at the negatives, I couldn’t help but be elated at what I saw.

I had read that the Cooke Amotal lens was quite good, so good in fact that people have converted them to Leica Thread Mount and used them on digital cameras, but looking at the scanned images on my computer screen, I was amazed at the sharpness and clarity. These images have an almost 3D digital quality that jumps out of the screen. Look at the image of the tombstone for “Salvatore Zona” and the tombstone appears to hover above the background.

Taylor, Taylor, & Hobson applied a durable anti-reflective coating to the outer surfaces of the Cooke Amotal which was not always consistently done in 1948 when this camera was first made. We would not see widespread adoption of coated lenses in some cases until the mid 1950s.

Although I never attempted to get any bokeh specific shots, the images that show out of focus details look great. I’ve never been a fan of highly distracting “bokeh bubbles” so seeing a creamy softness to the backgrounds really pleases me.

If I had one complaint, it does seem as though shots involving the sky look a bit blown out, which could be the result of some internal haze in the lens, and I’ll admit to not examining this lens too closely as it was a short term loan, but aside from that, these images came out perfect.

What little I can nit pick about this camera is extremely minor. This is a 70+ year old precision instrument that largely works exactly how it did when it first rolled off the assembly line and that’s something that never ceases to amaze me. How many automobiles, appliances, or other mechanical devices work just as good as they did nearly three quarters of a century after they were made.

With my almost universal praise for the Foton, I can’t help but wonder what could have been, had this camera been a little less expensive and if it had a better selection of lenses. The availability of only 2 lenses at launch and no wide angle lenses was a serious misstep for Bell & Howell. They had to have known the importance of a good lens selection, so why weren’t more available. Theres so much that is good about the Foton, I can only imagine what the Foton II, or any other follow ups to this camera might have looked like. Maybe the company would have released a less expensive mid range camera that had a tradtional lever wind, but had similar styling and the same great lenses.

I feel confident in declaring the Bell & Howell Foton to be a masterpiece of a camera, and although I only had it for a very short window of time, I can already wholeheartedly say this is my favorite camera I have ever used, in any form factor, by any manufacturer, from any time period, ever. Can it ever get any better than this?

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Foton

https://cameraquest.com/foton.htm

http://www.vintagephoto.tv/foton.shtml

https://photofilmcamera.com/bell-howell-35mm-rf-foton-1948

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=167628

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/bell-howell-foton-camera.278368/

“I can already wholeheartedly say this is my favorite camera I have ever used, in any form factor, by any manufacturer, from any time period, ever.”

I take it that you like it, Mike.

A truly remarkable camera and, along with Kodak’s Ektra, shows what might have been with the US camera manufacturing industry had they taken it really seriously, even though they were coming up against the might of Germany in this respect. But I believe that in setting out to make “the best” both cameras were unnecessarily complicated, almost form over function.

Thanks for the very informative video. What a palaver to load a film. Sports photographers may well have warmed to the 4fps, but then they’d be brought back down to earth when re-loading. Price may have been not the only factor mitigating sales success. And then you mention the apparent unreliability of the shutter. A work in progress?

Given its rarity and price now, one strictly for collector interest only, IMO.

These are beautiful cameras inside and out. I apprenticed in Chicago and one of the men I worked with worked at B&H during the years that camera was manufactured He said that cameras were not made until an order was placed rather than mass producing them. I have repaired several and they are really interesting in their design. The shutter is unique fitting into the curiosity shop of camera designs and the idea of “T-stop” also was another feature that relegated it to the top shelf as well.

Thanks for the additional feedback, Frank! These cameras certainly are special, and it is cool that you have had an opportunity to see how they work!

I like it. I would like some history on the Bell and Howell Binoculars. Was Leica involved

Bell & Howell was an American company and Leitz was in Germany. It is unlikely that the two ever collaborated on the same binoculars.