This is a Kodak Ektra, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by the Eastman Kodak Corporation between the years 1941 and 1948. It was at the time of it’s release, and still is today, the most advanced and feature rich American made 35mm camera ever built. Designed to compete with German cameras like the Leica and Contax, the Ektra matched in terms of quality and had features that no other German camera had, such as an adjustable focal length viewfinder and rangefinder, a magazine loading film back, and a range of lenses from 35mm to 153mm. Kodak spared no expense making the greatest camera they could possibly make, but that meant it also had a very high price that kept sales low during it’s 7 year production run. As a result of it’s high quality, unique features, and rarity, the Kodak Ektra is one of the most desirable cameras by collectors and examples such as this one in working condition, sell for quite a bit of money.

This is a Kodak Ektra, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by the Eastman Kodak Corporation between the years 1941 and 1948. It was at the time of it’s release, and still is today, the most advanced and feature rich American made 35mm camera ever built. Designed to compete with German cameras like the Leica and Contax, the Ektra matched in terms of quality and had features that no other German camera had, such as an adjustable focal length viewfinder and rangefinder, a magazine loading film back, and a range of lenses from 35mm to 153mm. Kodak spared no expense making the greatest camera they could possibly make, but that meant it also had a very high price that kept sales low during it’s 7 year production run. As a result of it’s high quality, unique features, and rarity, the Kodak Ektra is one of the most desirable cameras by collectors and examples such as this one in working condition, sell for quite a bit of money.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.9 Kodak Ektar coated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Ektra Breech Lock Screw Mount

Focus: 3.5ft to Infinity using the Rangefinder, 50 f/1.9 lens focuses down to 1.5ft

Viewfinder: 50mm – 254mm Adjustable Varifocal Viewfinder with Separate Split Image 1.6x Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe, Requires External Shutter Release Sync Cord

Weight: 1048 grams (w/ lens), 740 (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_ektra.pdf

Repair Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/EktraRepairManual.pdf (Large File: 440MB!)

How these ratings work |

The Kodak Ektra was not only Kodak’s highest spec 35mm camera they ever built, but it was also one of the highest spec American cameras of any time ever made. The Ektra is chock full of innovative features such as an adjustable focal length viewfinder, an interchangeable magazine film back, a unique lens mount with the world’s first complete lens system with Lumenized coatings, and much more. When it was new, the Ektra was extremely expensive, and it remains so in today’s collectors market as used examples in good shape easily fetch well over $1000. This is a fantastic camera that delivers fantastic results, and if you ever have an opportunity to add one to your collection for a reasonable price, I strongly recommend it! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for complete awesomeness | ||||||

| Final Score | 16.4 | ||||||

Special Thanks

Nearly all my reviews contain information sourced from a variety of websites, articles, blogs, magazine articles, or sometimes even verbal information I collect while researching each camera. I typically try to credit each of my sources, especially when a large amount of information comes from the same source. For this article however, I have 3 people in particular who, without their help, this article wouldn’t have been possible.

- Dan Hausman – Ohio Camera Collector’s Society and Ohio Camera Swap. The camera reviewed in this article belongs to Dan and he graciously loaned it to me for this review.

- Charlie Kamerman – kodakcollector.com. Charlie is a world renowned resource for Kodak information and sadly, his site seems to have disappeared off the net, but I found an archived copy on web.archive.org, plus a treasure trove of information Charlie has uploaded to Flickr.

- Marc Bergman – Marc is my source for a large number of period advertisements, and nearly every article I use in my Keppler’s Vault series. He has taken the time to scan in thousands of pages worth of old articles and ads from various camera magazines, and often helps me find stuff that I am looking for.

History

The Kodak Ektra is a fascinating camera. It defies the commonly held belief that American cameras were not up to the standards of German (and later Japanese) models, it has a huge list of features, many of which were firsts in a 35mm camera, and it’s rare. But to say that the fascination with the Ektra ends with the camera itself, deprives a collector of a fascinating story of how it came to be.

Of course, with any story, the specific details are sometimes quite vague, filled with theories and supposed facts that turned out to be nothing more than oft repeated, but incorrect rumors.

One of the most common rumors about the Ektra is that in the late 1930s, the US Government was anticipating war with Germany, and gave Kodak a bunch of money to build a top of the line precision camera to fill the void of German models that we might soon lose access to. A variation of that story is that Kodak pulled a left handed German employee from Kodak AG in Germany where the Kodak Retina was made to help build an all new American rangefinder at their headquarters in Rochester, NY. The location of many of the Ektra’s controls on the left side of the camera might suggest that a southpaw was in charge of design, and the camera’s precision quality being credited to someone working for August Nagel help establish rumors like these as they certainly seem plausible.

There’s even an elaborate story of a Japanese spy who in the days before the bombing of Pearl Harbor managed to sneak into the mountains of Hawaii and was seen using a Kodak Ektra photographing the military base in an effort to better prepare the oncoming fleet. As odd as it might seem for a Japanese spy to use an expensive American camera instead of a Japanese one or even a Leica which was much more common back then, and somehow get images shot, developed, and taken back to Japanese command, this story actually is based on something that really happened.

Of course, what happened wasn’t a Japanese spy, rather an actor photographed in an effort to recreate a fake event for a military propaganda film put together in 1942 by the Army Pictorial Service in a series of indoctrination movies called “Know Your Enemy” (clip begins at 47:22). The camera seen in the movie was in fact, a Kodak Ektra, as the Army would have had access to them through the Signal Corps.

It’s stories like these that help boost the “lore” of highly desirable cameras like the Kodak Ektra, but the real story is that in the late 1930s, Kodak did foresee a disruption in supply of precision German cameras and sought out to develop one of their own. Instead of a left handed German engineer, they turned to a (not left handed) Hungarian optical designer named Joseph Mihalyi who emigrated to the United States in 1907, and was already working for Kodak on a variety of projects.

Mihalyi was a distinguished designer, at one point receiving a Presidential Citation by President Harry Truman and had influence on a number of other Kodak cameras such as the Super Six 20, Bantam Special, and the Medalist. He would continue to work for Kodak until his retirement in 1954. He would pass away on December 10, 1965.

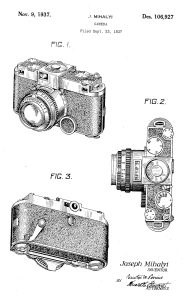

Work had already begun on the Ektra as early as November 9, 1937 as a US Patent Design application was filed by Joseph Mihalyi to the US Patent office showing the design of Mihalyi’s as of yet unnamed camera.

Comparing the illustrations in the patent on the left to the final product, it is interesting to me how much of the Ektra’s final design such as the location of the various dials on the top plate, exposure counter, and rapid film advance lever, were already incorporated into this patent from 1937 suggesting that initial design work had begun quite a bit earlier.

On June 7, 1938 another patent application filed by Mihalyi for a new shutter clearly shows the Ektra camera that it was to be used in. Reading part of the description of the shutter on pages 6 and 7, it describes an entirely new method for designing the slow speed shutter mechanism and a shutter that travels from left to right, confirming that the focal plane shutter in the Ektra was not based on any existing German or Japanese designs. This patent was eventually given the number 2,203,657 on June 4, 1940 and can be seen in it’s entirety below.

By 1939, the working name of Kodak’s new camera was the Super Kodak 35, of which at least one prototype exists. According to the now defunct Ektra Registry page, the Super Kodak 35 prototype with serial number #106 is shown below. (Images are all courtesy of Charlie Kamerman)

The Super Kodak 35 prototype looks much like the finished Ektra, with only a few cosmetic changes. Up front, the design of the main viewfinder window lacks the bezel of the finished model and of course the name Ektra is not present. Prototype lenses had the word “Anastigmat” on them, whereas finished lenses did not.

On top, the shutter speed selector is very different, looking more like a large wheel than a pull up knob. The self timer lever is missing (although a hole is present), there is no red window next to the exposure counter that indicates the shutter being cocked, and there is no accessory shoe.

In 1939, Kodak would release a 2 volume book titled “Major Developments in New Apparatus” which detailed a large number of upcoming projects including revisions to existing models and several all new models such as the Kodak Super 35.

Interestingly, Kodak had been working on a medium format version of the Super Kodak 35 which shot twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures on Kodak’s 620 roll film called the “Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter (E-1106)”. It would have come with an 80mm f/2.3 Kodak Anastigmat Ektar 6-element lens and shared many of the same parts as the Super Kodak 35 including most of the shutter, exposure counter, self timer, rangefinder, the viewfinder, and many of the same knobs on the top plate. The camera would have also had an interchangeable lens mount and a completely removable film back (although no magazine support) making it a pretty high end medium format camera. Unlike the Super Kodak 35 however, this camera would never make it past the prototype stage, but an image of it can be seen to the right.

The finished version of the Kodak Ektra was quite an ambitious camera, but it would seem that Kodak originally had even more ambitious plans as the 1939 document details a few features that never made it into the finished version. The highlights are:

- Nine lenses were planned instead of the six that were eventually produced. The three lenses that never made it were:

- 50mm f/1.5 Ektar (formula 315, focuses down to 1.5ft)

- 85mm f/1.6 Ektar (formula 160R)

- 254mm f/4.5 Ektar (4-elements, focuses down to 6ft)

- Wind up motor drive replacing the standard magazine. A single wind would allow for up to 12 exposures to be taken without having to re-wind the motor, advancing the film and cocking the shutter after each press of the shutter release.

- Optional photo electric unit (exposure meter) with automatic exposure capability. Cameras with this feature would have been an entirely different “deluxe” model with a different rangefinder that includes aperture priority automatic exposure by automatically varying shutter speeds between 1/25 and 1/1000 based on available light.

If you’d like the read the entire section on the Kodak Super 35, I have included the relevant pages as a PDF below.

The decision to put many of the camera’s controls on the left side was not due to a preference for left handed people, rather the exact opposite. Mihalyi believed that right handed people are also right hand dominant and therefore have stronger right hands which are better suited to holding and stabilizing a heavy camera like the Ektra. The right hand should be tasked with carrying and keeping the camera steady, while the weaker left hand would handle tasks like film advance, changing shutter speeds, and pressing the shutter release.

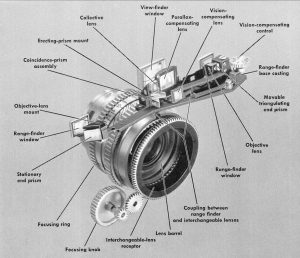

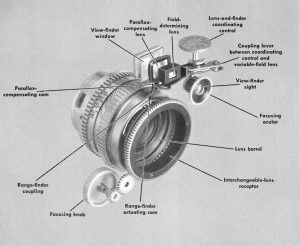

In addition to being an adept camera designer, Joseph Mihalyi also had a lot of experience with military optical design, and he put his experience to work with the Ektra’s rangefinder. A rangefinder is a basic mechanism in which the same image is seen through two windows, separated by a specific distance known as “base length”. One of the two windows is straight through and with the use of prisms or mirrors, light is redirected through a second, moving window. When the second window produces an image that perfectly lines up with the image seen through the first window, the angle can be used to calculate the distance of the object from the rangefinder.

Generally speaking, the wider the base length of a rangefinder, the more accurate it can be at great distances. Since most 35mm rangefinder cameras have lenses with focal lengths between 35 – 100mm, the width of the rangefinder doesn’t need to be that extreme. Mihalyi wanted to go well beyond the typical rangefinder focal length of 100mm and support a lens with a 254mm focal length (which was never actually built). To accomplish this, the base length of the Ektra’s rangefinder is an astounding 104mm, making it the widest rangefinder on any 35mm camera ever made. For comparison’s sake here are the base lengths of several popular rangefinder cameras.

- Olympus XA – 16mm

- Voigtländer Bessa R – 37mm

- Leica II/III series – 39mm

- Nikon SP – 58mm

- Leica M3 – 68.5mm

For the Pros: Yes I know my explanation completely eliminates magnification ratio for effective base length, but that’s beyond the scope of this discussion. I am merely trying to convey how gloriously big the Ektra’s rangefinder is. For a good explanation of Effective Base Length, check out this article.

It is clear Mihalyi put a lot of effort into the rangefinder, but he didn’t neglect the viewfinder either. The primary viewfinder has automatic parallax correction and an adjustable varifocal lens system which allows it to “zoom” from 50mm all the way to 254mm to accommodate a planned (but never produced) monster telephoto lens. All rangefinder cameras to this point (and even after) required either auxiliary viewfinders or multiple frame lines in a single viewfinder in order to compose an image using other lenses built for them. With the Ektra, if you wanted to use any of the 90mm, 135mm or 153mm lenses, you simply mounted the lens, and turned a dial on the top of the camera to the corresponding focal length and the viewfinder would adjust to that focal length. The adjustable viewfinder could only accommodate telephoto lenses, and not wide angles. For the Ektra’s 35mm f/3.3 lens, an auxiliary finder lens was provided.

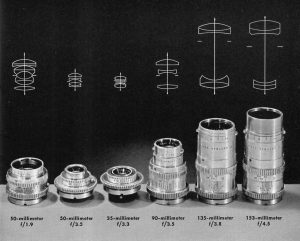

Upon the Ektra’s release, there were six lenses available which is more than any other rangefinder system at launch, made by any other company, not even those made by Leica, Nippon Kogaku, or Canon. All of the Ektra’s lenses were built by Kodak and had hard Lumenized coatings, which made it the first camera system of any kind, made by any company in which every lens available was coated. There were an estimated 2000 each of the 35mm, 90mm, and 135mm lenses, but only about 400 of the 153mm lenses made, making them the rarest.

In addition to the six lenses and a whole load of filters, hoods, and other lens accessories, the Ektra also had a right angle viewfinder, top down viewfinder, ground glass focusing back, and a closeup rangefinder available to round out the system.

The Ektra’s shutter was of the cloth focal plane type, but it was unique among other shutters and not based on any existing designs. All cloth focal plane shutters use two curtains that travel horizontally across the film plane at a fixed speed usually around 1/50 or 1/60 of a second. The “speed” of the shutter chosen by the photographer is actually determined by a gap in between the first and second curtains that allow for a predetermined amount of light to pass through. For slow shutter speeds, the first curtain opens, and the second curtain waits whatever length of time the photographer has chosen, and then closes. Fast shutter speeds are achieved by the first curtain starting to open, and then the second curtain beginning to close before the first curtain has finished opening, creating a “slit” of light to pass through. At speeds of 1/100 of a second, the gap is still pretty big, but at 1/1000, there is only a narrow slit of light passing between the curtains.

The Ektra shutter follows this same principle, but differs in that the gap of the “slit” is set using the shutter speed selector prior to the shutter firing, rather than at the moment of exposure. With most cloth focal plane shutters, the two curtains are both closed until the shutter release is pressed. The first curtain separates from the second, creating a gap, and then at whichever point the desired gap is reached, the second curtain begins to close.

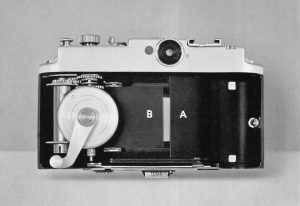

With the Ektra, the gap between the first (A in the image to the left) and second (B) curtains is already set prior to releasing the shutter, and and locked into position throughout the entire travel of both curtains. This method was said to be more consistent because there’s never a point where the two curtains are beginning or ending their gap.

Another innovative feature of the Ektra which allowed it to stand above other professional cameras was the interchangeable magazine back. Prior to the Ektra, if a photographer had a roll of film in his camera and he wanted to switch films mid roll, he had to either rewind the partially shot roll of film back into it’s cassette, noting how many exposures had already been taken so that upon continuing that roll, he would advance the film back to the unexposed section of the roll, and then remove it, or in the case of cameras like the Ihagee Exakta, use an internal slitter to cut the exposed section out, remove it, and then reinsert a different unexposed roll.

With the Ektra, you could simply remove the entire film compartment (or magazine) from the camera, containing the entire roll of film and both spools, and swap it with another. Of course, to do this, the photographer would need multiple magazine backs, which at the time cost $55 each. For that money, each magazine back was custom fitted to the body of the camera to ensure a perfect fit that wouldn’t allow any light leaks.

Kodak spared no expense in both the performance and durability of the camera. Every single Ektra body and lens were fully tested by Kodak before leaving the factory. No feature was overlooked to be as reliable as possible, making for what they had hoped would be an eternally dependable high performance camera.

Upon it’s release, the Kodak Ektra sold with the 50mm f/3.5 Ektar lens for $235 or with the 50mm f/1.9 lens for $300. It could be priced with any of the other four lenses as well, but does not appear to have been offered body only. These prices when adjusted for inflation compare to $4100 and $5225 today, making it quite an expensive camera. A complete price list from Abe Camera Exchange’s 1941 catalog of the Ektra, it’s lenses, and several other accessories is to the left.

Kodak advertised the Ektra with the tag line, “The World’s Most Distinguished Camera” creating a variety of printed enlargements taken with an Ektra, along with this very unique looking display that would sit on the counter at camera stores all over the country. With each display would have been a 40 page promotional brochure which was meant to fully show off the Ektra’s merits.

Here is an entire PDF scan courtesy of Pacific Rim Camera, of that promotional brochure that Kodak had created for the Ektra.

It is difficult to measure how well any consumer product sold when it was released in the middle of one of the most significant wars in human history. We know that parts of the Ektra were built to military specifications, and Kodak already had a history of making products directly with the military in mind, so we know for sure that at least some Ektras were used by the US Government. We also know that production of the Ektra resumed after the war and lasted until about 1948, so there definitely were some sold to regular consumers as well. But how many?

Brian Coe’s book, Kodak Cameras: The First Hundred Years gives an estimate of 2000 Ektras being produced, but a retrospective article published in the April 1975 issue of Modern Photography suggests a number of 2490. Whichever of the two is right is anyone’s guess, but with less than 2500 produced, how many were used by the military and how many were sold to civilians? If 2000 of those were for the military and only 500 were bought by regular people, that would suggest the camera didn’t do as well as if only 200 were for the military and 2300 were bought by regular people.

Whatever the break down is, the Ektra clearly didn’t fly off the shelves largely because of it’s price and complexity. Even in situations where a professional photographer was willing to plunk down at least $300 for a new camera, would he or she taken the plunge with this new Kodak, or waited for Germany to start making Leicas and Contaxes again? We’ll never know.

In 1948 an updated model called the Ektra II was developed, but never officially went on sale. At least three, possibly four, are known to exist all with 7xxx serial numbers. According to Brian Coe’s book, the new camera was primarily designed to work with an optional spring wound motorized back that was originally planned back in the late 1930s for the original model, but never implemented. Why this feature was originally scrapped, but later re-introduced could possibly have allowed the Ektra II to better compete with the Bell & Howell Foton, which went on sale the same year.

From it’s outward appearance, there is little else to distinguish the Ektra II from the original model. The most noticeable change is a redesign of the front main viewfinder window, which has a different bezel around it, but doesn’t appear any larger or smaller. The viewfinder focal length adjustment wheel omits the setting for the 254mm lens which was never developed, and only has a range from 50 – 150mm. This simplification of the viewfinder could suggest some cost cutting was in play to bring the price of the camera down. There are a few other very minor cosmetic differences such as a revised design for the exposure counter window, and the markings on the shutter speed disc.

A number of sites, including Camera-wiki.org’s Ektra page suggests one other improvement, which was an additional yellow tinted sliding mask in the viewfinder to support the 35mm wide angle lens. I am not sure to the validity of this however, as upon inspection of several high resolution images of an Ektra II, I see no outward changes supporting this 35mm mask.

There is little else out there that gives definitive specs for the Ektra II, and it’s possible more features were planned, but from the few prototypes that do exist, it’s clear that whatever the Ektra II was supposed to be, it would have only been a minor revision to the original camera, leaving most of it’s design and features alone.

Kodak officially discontinued the Ektra in June 1948 with the last few models sold built using existing parts. Inflation had increased dramatically in the years after it’s release in 1941, and the original $300 price tag was no longer enough to cover the costs to make the camera. In order to remain profitable, it is estimated that Kodak would have had to raise the price of the camera to as high as $700 which they were unwilling to do.

Fun Fact: The Kodak Ektra has a total of 667 individual parts, made from a total of 88 different materials, making it quite the complex camera!

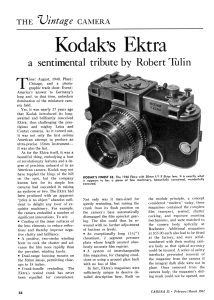

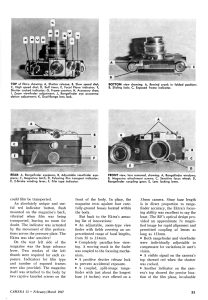

The Ektra was extremely expensive and not that many were sold, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t fondly remembered. In the decades that would follow, it would remain a desirable camera, both by collectors and photographers alike. In the Feb/March 1967 issue of Camera 35 magazine, the article below was published in which Robert Tulin fondly tells the tale of Kodak’s ultimate camera. The article is half review and half retrospective, introducing what was likely a new generation of photographers who didn’t remember it.

Here is a gallery of some other articles and various Ektra related tidbits that Marc Bergman found for me, while I was researching this article.

Today, the Kodak Ektra is a rather notorious camera. It’s reputation for being an over the top design, with a unique, but unreliable shutter that sold poorly is well known. There are those who collect American, German, Japanese, or Soviet cameras, but I am quite certain that no matter what particular area of interest a collector might have, he or she would find it hard to resist a nice Kodak Ektra at a nice price.

Currently, the going rate for sold Ektras on eBay is between $821 and $1395, depending on condition and accessories. This is on par with that of Leica M3s and Nikon SPs which suggests their used market value is similar to those, but of course this being a much rarer camera, finding one worth buying is a challenge. If $1000 is within your budget for a used film camera, and you like quality and uniqueness, I cannot think of a better option than the Kodak Ektra.

My Thoughts

Of all the cameras I have ever reviewed for this site, or any that I have lusted after, or pined to one day hold, the Kodak Ektra was the one I wanted the most. I have a fondness for Kodak cameras and have previously declared the Medalist to be one of my all time favorites, one that if I had to sell my collection, would be one of the last to go.

I’ve shot nearly every Kodak ever made, but not the Ektra, their crown jewel of 35mm cameras. The prices for them in anywhere near decent condition on eBay were prohibitively high, so I tried foreign auctions in Japan and other marketplaces and always came up empty handed. I thought perhaps I could borrow one from another collector, so I asked nicely, I pleaded, I begged to borrow one and then one day while talking with fellow collector, Dan Hausman of the Ohio Camera Swap and The Ohio Camera Collector’s Society graciously offered to loan me a working Ektra that he had planned on putting up for sale. Dan confirmed that the camera had previously been serviced by a local repairman and should work fine. Elated, we exchanged emails and home addresses and a week or so later, I had a package at my doorstep.

My first reaction to holding the Ektra can best be described as being starstruck, much like a teenager might feel upon meeting his or her idol. I couldn’t believe that I finally had a freaking Kodak Ektra in my hands, and it worked too!

My second reaction was, boy this thing is heavy! With the f/1.9 Ektar lens mounted, the Ektra weighs a whopping 1048 grams (2.3 lbs) which makes it the heaviest 35mm rangefinder I’ve ever handled. For comparison a Nikon F w/ Standard Prism and Nikkor 50/2 lens weighs 903 grams and a Rolleiflex K4A weighs in at 978 grams.

The Ektra isn’t just imposing because of it’s weight, this is a feature rich camera with a ton of knobs, levers, and other gadgets, and nothing more proves that point than the top plate.

Starting in the upper left corner is a retard dial for the slow speed governor. Like most cameras of the day, the Ektra has a separate dial for the slow speeds, and this dial is used for speeds of 1 second to 1/10 plus Bulb. In order to use these speeds, the main shutter speed dial must be set to 1/25. For all other speeds, it must be set to the circle position.

Next to it is the main speed selector for shutter speeds from 1/25 to 1/1000. To change speeds, lift up on the knurled ring and rotate until the desired speed is selected. The shutter must be cocked before you can properly change speeds otherwise the selected speed won’t correspond to the dot. In the previous image to the left, the shutter is not cocked, which is why the dot is beyond the 1000 mark.

In the bottom left corner is the threaded shutter release button which normally has a screw in tip which is missing on this particular example. The Ektra was not built with any type of internal flash sync. For flash photography, Kodak sold an external flash synchronizer that would screw into the threaded hole on the shutter release. Opposite of the shutter release is the 12-second self timer lever. The shutter release button has a shutter lock which is not obvious is there. To activate it, lift up on the shutter release button and rotate it counterclockwise about 90 degrees and drop it into position. There is a red line on the shaft of the button to indicate which position it is in. With the red line to the right, it’s locked, to the back of the camera, it’s unlocked.

The large dial in the center of the top plate is the exposure counter. This counter is additive and must be manually reset after installing a new roll of film or magazine back. Near the 7 o’clock position around the counter is a small oval window which shows a red mark when the shutter is not cocked as a warning to not attempt to change shutter speeds.

The large dial on the right of the top plate is the focal length selector for the main viewfinder. This has a range from 50mm to 254mm which was to accommodate a 254mm lens that was planned, but never built. This feature is one of the neatest features of the whole Ektra, and would have been immensely useful had I had one of the telephoto lenses. Sadly, this feature does not accommodate the 35mm wide angle lens, which requires it’s own auxiliary viewfinder. Beneath this window is the accessory shoe for a flash or for other accessories.

Finally, the smaller dial is called the “Eye Accommodation Dial” which functions as a sort of diopter for the rangefinder, allowing for between + / – 3 correction on that window.

The back of the Ektra is more interesting than most cameras. Starting at the top is the smaller rangefinder window and much larger (but still not that big) main viewfinder that are intentionally placed very close together in an effort to shorten the time required to move your eye from one window to the other. The large wheel around the main viewfinder is an adjustable diopter that allows for a pretty wide swing of adjustment to compensate for people with less than ideal vision. Adjusting this diopter is a requirement when turning the adjustable focus setting for the viewfinder as it is of a “varifocal” design in which focus needs to be adjusted at different focal lengths.

Immediately below the viewfinder is the door look which looks unlike anything I’ve ever seen, and sadly, is one of the weakest links of the camera. In the image to the left, the door is in the locked position. To unlock it, you need to turn the wheel 180 degrees and then push it to the left. The problem is on this example is that there is little to no resistance on this wheel and it can move on it’s own through regular use. At least once, the door almost came open with film in it. It’s entirely plausible that this looseness is a symptom of this particular Ektra, and others are much tighter, but at the very least it’s something you’d want to be mindful of.

To the right of the door lock is a strange little red dot whose function is not immediately obvious. This is a film transport indicator that “jiggles” as film advances from the cassette to the take up spool. The Ektra lacks a rewind knob that would rotate during normal transport, so this is your only indication of proper film travel.

Beneath the door lock is a film reminder disc which is typical of most mid century Kodak cameras and includes most of the available Kodak film stocks of the day.

Finally, that large lever on the left is the film advance lever. I am probably wrong on this as every time I post a review where I say something with certainty, I am later proven wrong, but I think the Ektra was the first 35mm camera with a film advance lever rather than a knob. It’s certainly the first with it on the rear door. Like the other left handed controls, the lever is designed to be operated with your left thumb and is surprisingly easy to move. It requires one full motion plus about three fourths of a second motion to properly advance and cock the shutter for the next frame.

I applaud Kodak’s effort with including a film advance lever as it was certainly unique in 1941, and normally works quite well, but due to the fact that it needs to operate through a removable door, I found a couple instances where the sprockets on the large wheel inside the door weren’t properly meshing with the toothed gear inside of the camera. In the image to the right, you can see the two sets of gears, one on the door, and the other just above the top film sprocket shaft. It works, but I can definitely see that under heavy and repeated use, this likely was a common fail point of Ektras.

Aside from the bottom hinged rear door, loading film is a surprisingly modern affair, especially considering the complexity of other parts of the Ektra. Film travels from right to left into a fixed take up spool. Install a new cassette into the cavity on the right and insert the leader into the slot on the spool, making sure to hook the single tooth into one of the sprocket holes. The take up spool has knurled edges on both the top and bottom which make it easy to manually turn a couple of times to make sure the film is properly attached, and then you simply shut the door.

Flip the Ektra over, and like the back, the bottom is also more interesting than most cameras with a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, a fold out rewind lever on the left, and a partial exposure counter for the magazine on the right. When you’ve reached the end of a roll of film, there is no rewind button that needs to be pressed, simply fold out the rewind handle and turn it in the direction of the arrow.

Magazine you say? That’s right! The Ektra has a removable magazine back! The term “magazine back” likely comes from firearm magazines which are removable containers that contain bullets (or film) that can be quickly swapped into and out of the camera with the film still in it. The Kodak Ektra was aimed at the professional photographer who might have the need to quickly switch back and forth between black and white and color film, or simply different types of film. In any other camera, you’d need to either finish the first roll, or rewind it back into the cassette before removing the partially shot roll, and then load in a new roll.

With the Ektra, you simply slide that long lever in the center of the bottom of the camera from the Lock (film gate is open) to the Unlock (film gate is closed). Doing this slides a metal door in front of the opening of the film gate to protect the film inside, so that when you remove it from the camera, light does not expose the film and ruin it.

Removing the magazine back is a multi step process that first requires that you advance the film lever to cock the shutter first, or the back will not come off (ask me how I know). Since you’ve cocked the shutter, you should use the shutter release lock to prevent accidental firing of the shutter with the back removed. Next, you need to move the slider on the bottom from the Lock to Unlock position to both unlock the magazine and also slide a door over the film gate. Finally, unscrew both of the round knobs on the left and right edges of the front of the camera and the entire back comes off.

With the magazine removed, the film is safely stored inside, protected from light while you swap in another magazine. Remember the partial exposure counter on the bottom? You should set that counter to match the main counter, so you can remember how many exposures have been taken on a partially shot magazine before putting it back into the camera.

When the Ektra was a current model, replacement magazines could be purchased from Kodak at a cost of $55 each ($958 when converted from 1941 to 2019 and $600 converted from 1948 to 2019). With the cost of the magazine, this included a custom fitting of the back to each body for a perfect fit. When looking at the bottom of the Ektra body and each matched magazine, you should see a matching serial number to indicate that you have a matched pair. In the image to the right, you can see the number “A-1331” on both. This discouraged trading or selling of magazines on the used or third party markets as an unmatched pair might have fitment issues.

Removing the lens from the Ektra is not immediately obvious, but isn’t nearly the impossible act that some sites suggest. The Ektra’s mount is a unique breech lock screw mount in which you must unscrew a collar around the perimeter of the lens to detach the lens from the body, but before you can do this, you must release a lock beneath the lens on the side of the block of metal that has the tripod socket on it. Press and hold this lock while simultaneously unscrewing the collar around the lens and it will eventually come off. While more elaborate than a simple screw mount, it requires only a modicum of dexterity, compared to other breech lock lens mounts used by other manufacturers over the years.

Putting the lens back onto the camera requires you align two notches inside of the lens mount to matching tabs on the inside of the lens and then rotating the collar in the opposite direction that you used to remove the lens. You’ll feel and hear a few clicks of the lock engaging when you’ve reached the point where the lens is fully attached.

The 50mm f/1.9 Ektar is quite a well built and robust lens. There’s 7 glass elements inside an all metal body that weighs 308 grams by itself. The aperture ring is closest to the front edge of the lens, immediately in front of the large knurled focus ring. Both rings are easy to locate with the camera to your eye and have an excellent tactile feel. I am uncertain if this lens has ever been serviced in the past, but if it has not, I am doubly impressed with how well the lubricant used in it has held up.

There is also a second precision focus wheel on the front body of the camera near the 4 o’clock position around the lens mount. The position and design of this wheel is very similar to the precision focus wheel on the original Kodak Medalist, which was also designed by Joseph Mihayli.

The Ektra has separate windows for the parallax corrected viewfinder and rangefinder, which means there’s not much to see within the viewfinder, but of course the coolest feature of the camera is the adjustable focal length feature. In the images below, I show the same view through the viewfinder at 50mm, 100mm, and 254mm.

The Ektra’s rangefinder is magnified by 1.6x and is of the split image type in which the image is split horizontally into two images, one each taken from the two smaller windows on the front of the camera. This design was often used in earlier rangefinders and has the advantage of not needing a beamsplitter to split some of the light to achieve the coincident image of later rangefinders. As a result, split image rangefinders are often brighter and easier to use in lower light.

Like other split image rangefinders used in other Kodak cameras like the Medalist and Chevron, the Ektra’s uses glass prisms instead of mirrors, which in theory means that they should last forever as there’s no reflective material to flake off like older mirrors sometimes do. Despite this, the rangefinder in this Ektra did exhibit some type of fungus or dirt near the split image edge as seen in the image to the left. It did not affect the rangefinder’s performance however.

Like most rangefinders, there is a lower limit to how close the rangefinder can effectively focus, which in the Ektra is 3.5 feet. In the case of the 35mm wide angle and both 50mm lenses, the lens can focus down to 18 inches by pulling up on a small catch on the side of the lens while turning the focus ring past the 3.5ft mark. Normally, this catch prevents the lens from going below 3.5ft at which point the rangefinder no longer works. Each distance marking beyond this lock is indicated in red numbers.

Fun Fact: The CAMEROSITY date code on this 50mm f/1.9 Ektar lens suggests it was produced in 1940, a year before the Ektra’s release. Does that suggest this is a very early example, or did Kodak just have the lenses ready before the camera? If you know the answer, please let me know in the comments section below.

When focusing closer than 3.5 feet, you’ll either need to use some type of external measuring device, or you could buy the Kodak Ektra Close Focusing Rangefinder, which mounts to the accessory shoe and permits focusing down to 18 inches.

With the film compartment’s bottom hinged door, there is not much to see on either side of the Ektra. Both the left and right sides look like mirror images of each other.

When handling an Ektra for the first time, it’s size, weight, and control layout are intimidating. Add to that the rarity and market value of clean working examples, this is definitely a camera you don’t want to misuse. If you are lucky enough to handle an Ektra, a refresher of the manual before each use is a good idea.

My Results

The arrival of the Ektra coincided with an unusually rainy June which meant that I had to keep postponing my first adventures with the camera. When the skies finally cleared and it was time to take it out, I thought what better film to shoot in a Kodak Ektra, than Kodak Ektar 100! Ektar is a fine grained color film that is known for very vibrant colors, but low tolerance for over or under exposure, so it was a bit of a risk to shoot a film with less latitude in a 78 year old camera that I had never used before. When I was finished with the Ektra, I threw in a roll of Rollei RPX 25 to see how it performed with a slow speed black and white film.

Even though the Kodak Ektra was designed as a top of the line camera for professionals with the best lenses that money could buy, I’m still impressed with these images. There aren’t too many people shooting Ektras any more because of their rarity, value, and the fact that they usually don’t work, so I was overly ecstatic as each image kept popping up on my screen as my scanner scanned each image.

The results from the 7-element in 4 groups, Gauss design f/1.9 Ektar lens were astounding! As good as anything I’ve ever seen on film. If these lenses weren’t so rare, I’d have no doubt that they would be big favorites for people adapting them to digital. Does an adapter for Ektra mount lenses even exist? I have no idea.

People often (rightfully so) give a lot of credit to Nippon Kogaku and their excellent lens coatings on their post-war Nikkor lenses, but Kodak’s Lumenized coatings were top notch as well, delivering sharp and vivid colors, void of flaring or any contrast issues seen on uncoated and early coated lenses.

Is there anything in these images that a Nikon SLR or any German rangefinder couldn’t have made? Probably not, but that’s not the point of shooting old cameras. The Ektra is a masterpiece of a camera that delivers A+ results in every image. It’s not the easiest model to use, but that’s part of what makes it interesting. When it comes to collecting and shooting old cameras, it simply doesn’t get any better than the Ektra.

In last week’s review of the Bell & Howell Foton, I was so impressed with it that I declared it the best camera I’ve ever shot, and now, only a week later, man, I don’t know how I feel anymore. How often do you get to shoot two of the best cameras ever made back to back?

I wasn’t initially in love with the Ektra’s ergonomics, but got used to them pretty quickly. By my second roll, I was instinctively shooting it like it was any other camera. In regards to the shutter release, once I tried rotating the Ektra 90 degrees into portrait orientation, I found that I liked it’s location as it was really easy to reach with my left thumb (see my selfie in the gallery above). The shutter in the Ektra is a bit noisy, but gives a satisfying double-click sound when firing. Although I only had access to a single 50mm lens, I found it quite entertaining to turn the adjustment wheel and imagine what a telephoto lens would have been like on this camera.

I had been after an Ektra for quite some time before getting a hold of this one, and I read a number of disparaging comments from various collectors saying the Ektra was an unreliable mess, a camera that aimed too high and miserably failed due to an over ambitious design. While it’s low production numbers do suggest an over ambitious design that didn’t sell all too well, I doubt that many of those Ektra naysayers have ever handled, or even shot one. I won’t dispute it’s low production numbers, but as a user, the Ektra delivers in a big way.

For those of you who say they’re unreliable or too expensive. The going rate for an Ektra on eBay is a little over $1000, but so is the Nikon SP or Leica M3, and while those two cameras might have a better reputation for reliability, how many collectors who are in the market for a $1000+ vintage camera would bat an eye at a complete CLA for them? The Ektra is no different. Sure, its a bit odd, but it’s got features like the adjustable viewfinder and a magazine back that those don’t. It’s also more than a decade older than those cameras too, yet I feel comfortable declaring the optical quality of Ektra lenses to be on par with anything the Japanese or German made, or ever would make.

Simply, the Kodak Ektra is a fascinating camera that was innovative in design and features, built to a quality standard as high as anything at the time of it’s release, and while anyone is unlikely to find one in perfect working order today, it is absolutely worthy of the prices being asked for them, plus that of a complete overhaul. And not to take anything away from any Leica or Nikon rangefinder, as they’re truly spectacular cameras too, but the Ektra is unique in nearly every way. Tell a serious collector that you collect German or Japanese rangefinders, and they’ll likely yawn, but show them a working Ektra and it’s images, and I guarantee you, they’ll notice.

With my declaration last week that the Bell & Howell Foton was my favorite camera ever, has my opinion changed? I don’t know. The Foton is a gorgeous and innovative camera too. Maybe one of these days I’ll put them both in a head to head test and reveal once and for all, which is my favorite… </purposeful_foreshadowing>

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.bnphoto.org/bnphoto/KodakEktra1.htm

https://www.cameraquest.com/ektra.htm

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Ektra

https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/ektracam.htm

http://web.archive.org/web/20130325120848/http://www.chicagophotographic.org/articles/ektra.htm (Archived)

You knocked this one out of the park! Awesome documentation from a historical narrative while never overlooking the usability aspects of a model that few will ever handle! Awesome!

Thanks for the kind words. It was definitely a pleasure to handle and shoot! Now if I could only manage to find one for my permanent collection!

Your article on the Kodak Ektra was very thorough and well written; very enjoyable and informative. Best wishes on finding the right Ektra for your collection.

John, thanks for the compliment! I am happy to report that after publishing this Ektra, I was able to come to an trade with it’s owner which allowed me to keep it in my permanent collection! This Ektra is now the most cherished camera in my collection!

The amount of work you have put into this review is nothing short of astounding – there is something to be read here for everyone, camera- and history buffs alike, as well as lots of data to please the GASeous. Your link are also most useful to data-addicted photo researchers such as I am.

I used as Ektra in the early 1960s when I was in my teens and just starting out in photography – it was owned by a local dentist who generously loaned me the camera and gave me some old film to experiment with. I still have several sheets of negatives I took in my home town in New Mexico, and while they aren’t exactly works of art, that’s more a reflection on the photographer than the camera. That Ektra was almost 25 years old by then and had been well used by its owner, but it certainly delivered the goods.

We need more intelligent and well-thought out reviews like this. i have bookmarked your excellent site and I will be returning in future to see what you have on offer. Please keep up the good work.

Dann in Australia

Dann, thank you for the kind words. I am glad you enjoyed the article and appreciate the work I put into it. Although I don’t always dig up as much great info as I did for the Ektra, I always put a lot of work into each review, so I am sure if you look around my site, you’ll find more reviews to read. If you liked the Ektra, I would recommend the Bell & Howell Foton as that’s another terrific high end American camera.

Mike:

Thus is the most complete review ever in theKodak Ektra

I am a physician (Cardiologist) in New Jersy, USA

I collect all rangefinder cameras and I agree the Ektra is the best of all.

I own 4 Ektras 1 fully funcionales and two on a repair man that I trust (the only one now working on this cameras in the USA)

I use my cameras every day but my advise is not to change magazines.

Special for me since my father used the Ektra un Cuba in 1945. Unfortunately the camera was lost in time after the catastrophe that swept Cuba.

Thanks for t

Your work and dedication

Alejandro Presilla MD

Alejandro, thank you for the kind words! I only have the one Ektra and it still works. What a wonderful camera and piece of history. I appreciate the feedback and the story about your father’s camera.

Mike I really enjoyed reading your article as I have had my grandfather’s Ektra for approx. 40 years and new little about this masterpiece. Now that I’m about his age when he gave it to me I would like to sell it and was wondering if you have any suggestions as to the best way to do so. I have the camera and 3 lenses, 2 backs, range aux. range finder, and a couple of filters all having been stored in an attache’ type case. I’m not sure if the camera is in full working condition. If you have time please advise.

Mike

Today I took my Ektra with a 50mm lens to NYC to little Island

A beautiful girl ask me sir what kind of camera is it

I am into film and never seen this camera before

I told her all the stories of the Ektra and your post

All thanks to you

Alejando

Thanks for the feedback Alejandro. It is good to see other people getting good use out of their Ektras!

Your information on this camera largely inspired me to find one for my collection. No shelf queens here though, I hope to get some use out of it. I found one with some lenses (all except the 50mm f/3.5). I don’t normally indulge like this but I decided to go for it, all for it to get stuck in USPS (don’t worry, i am not out anything). It’s been there for about a month now. I am loosing hope of ever seeing it. USPS was not my choice. Learned my lesson for not requiring FedEx or UPS.

Aww man, I am so sorry to hear that! Not only that you’re not going to get your camera but that a nice Ektra kit with multiple lenses may have gotten lost, or worse, destroyed! These cameras are rare enough, especially in working condition, that we can’t have them going missing! I will keep my fingers crossed that it will still one day show up!

Thank you for this excellent article and sharing all of the fascinating documentation regarding the Ektra. I only recently obtained one and agree wholeheartedly with you and the other enthusiasts about what a magnificent camera this is. As a note, for effective base length, it is my understanding that one simply multiplies the base length times the magnification of the rangefinder (or viewfinder where they are combined). Because the base length is remarkably long and the magnification of the rangefinder is remarkably high — both greater than any other camera of which I’m aware — the resulting figure of 166.4 is staggering.