This is a Perfex Speed Candid, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Candid Camera Corporation out of Chicago, Illinois between the years 1938 and 39. It was Candid’s first ever camera, and the first camera to bear the “Perfex” name, which after this model evolved into a semi-successful family of Perfex rangefinder and scale focus 35mm cameras. The Speed Camera is a large and heavy monstrosity that had the first American made 35mm focal plane shutter and managed to include nearly every popular feature for a 35mm camera of the time, including an uncoupled rangefinder, extinction meter, and interchangeable lens mount. The camera did not sell well, and thankfully, it’s designers went back to the drawing board for their next camera, the Perfex Forty-Four.

This is a Perfex Speed Candid, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Candid Camera Corporation out of Chicago, Illinois between the years 1938 and 39. It was Candid’s first ever camera, and the first camera to bear the “Perfex” name, which after this model evolved into a semi-successful family of Perfex rangefinder and scale focus 35mm cameras. The Speed Camera is a large and heavy monstrosity that had the first American made 35mm focal plane shutter and managed to include nearly every popular feature for a 35mm camera of the time, including an uncoupled rangefinder, extinction meter, and interchangeable lens mount. The camera did not sell well, and thankfully, it’s designers went back to the drawing board for their next camera, the Perfex Forty-Four.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/2.8 Graf Perfex Anastigmat uncoated 3-elements

Lens Mount: ~38mm or 1.5 inch Screw Mount

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder with Uncoupled Split Image Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Extinction Meter

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 810 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Perfex Speed Candid was the first camera made by the Candid Camera Company of Chicago and it shows. The feature set of the camera is quite ambitious with a rangefinder, focal plane shutter, extinction meter, and interchangeable lenses, but the design and ergonomics of the camera are terrible. Using the camera is a chore, the extinction meter is not helpful, and scale focusing is so much faster than the rangefinder, I can’t see how anyone would ever use it. But, if ugly cameras with strange ergonomics are your thing, then this could quite possibly be your perfect camera! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for unique and strange design, -1 for unique and strange design | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.4 | ||||||

History

The Perfex Speed Candid was made by a company called the Candid Camera Corporation, located in Chicago, IL. In the entire history of American photographic companies, the Chicagoland area wasn’t exactly known as a dominant force in the industry. In fact, some might say Chicago’s greatest claim to fame was an inexplicable number of cheap Bakelite cameras made under a dizzying number of companies and cameras like the Utility Manufacturing Corp with the Falcon camera, the Pickwik, Spartus Corp, Herold Manufacturing Corp, General Products Corp, ACRO Scientific Products Co., The Spencer Company, Metropolitan Industries with their Clix-O-Flex, Monarck Manufacturing Corp, and many, many others. Strangely, many of these companies all shared a similar address of 715 W. Lake St in Chicago. Camera-Wiki.org has a huge list of many of the companies and variations on these cheap cameras if you’d like to know more.

The Perfex Speed Candid was made by a company called the Candid Camera Corporation, located in Chicago, IL. In the entire history of American photographic companies, the Chicagoland area wasn’t exactly known as a dominant force in the industry. In fact, some might say Chicago’s greatest claim to fame was an inexplicable number of cheap Bakelite cameras made under a dizzying number of companies and cameras like the Utility Manufacturing Corp with the Falcon camera, the Pickwik, Spartus Corp, Herold Manufacturing Corp, General Products Corp, ACRO Scientific Products Co., The Spencer Company, Metropolitan Industries with their Clix-O-Flex, Monarck Manufacturing Corp, and many, many others. Strangely, many of these companies all shared a similar address of 715 W. Lake St in Chicago. Camera-Wiki.org has a huge list of many of the companies and variations on these cheap cameras if you’d like to know more.

It would seem that Chicago was only known for cheap Bakelite cameras, but there was one exception, the Candid Camera Corporation. Candid was formed in May, 1938 by Carl and Joseph Price, and Benjamin Edelman. Like Argus, these men reportedly had experience in the radio industry, possibly working for another mid western company, before turning their attention to making cameras. Their original address was on the 4th floor of a six-story building at 844 West Adams Street in downtown Chicago.

The company’s first camera was released in October 1938 and was called the Perfex Speed Candid. Built around a Bakelite body that strongly resembled the Argus A-series, the Perfex was a pretty sophisticated camera, featuring the first ever American made 35mm cloth focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/25 to 1/500, an uncoupled rangefinder, extinction meter, and an interchangeable helical focus mount.

The camera is most often seen with a 2 inch (~50mm) f/3.5 Graf-Perfex anastigmat lens, but there were 2 inch f/2.8, 4 inch f/4.5, and 6 inch f/4.5 auxiliary lenses available as well. These lenses were all made by a company called General Scientific Corp of Chicago. Whether this was a separate company or a subsidiary of the Candid Camera Corp is anyone’s guess.

For closeup work, an interchangeable ground glass focusing back was made available along with a set of extension tubes making the Speed Candid a rather flexible “system” camera.

Although using a lot of Bakelite in the construction of it’s body, the entire front of the camera along with the shutter box was made entirely of die-cast metal. The camera was very large and heavy and had terrible ergonomics making it clumsy and difficult to use. Despite the off-putting looks and difficult controls, the Speed Candid sold reasonably well. At least good enough to warrant an upgraded successor.

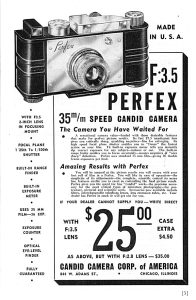

The Perfex Speed Candid was an incredible value in 1938 when it sold for only $25 with the Graf f/3.5 lens, and $35 with the f/2.8 lens seen here. The $25 price point meant it competed directly with the original Argus C and Univex Mercury CC which was considered a benchmark for the average American worker’s weekly salary. When adjusted for inflation, that price compares to about $450 today.

Throughout it’s run, there were a couple minor variations in the Speed Candid including a switch from Philips to flat screw heads, and a change in the typeface of the Perfex logo from all lowercase to having a capital “P”. There was also at least one that didn’t come with a rangefinder mounted to the top plate. Since there are screws that secure the rangefinder directly to the Bakelite, if it is removed, holes are left behind, so in the image to the left where the top plate is completely flat, it suggests it never had one mounted.

In 1939, an entirely new Perfex called the Forty-Four was released with an all new die-cast body, upgraded shutter, 3½” wide base coupled rangefinder, and flash hot shoe on top of the camera. The Forty-Four was a much better looking camera and it retained most of the Speed Candid’s best features such as the interchangeable lens mount, focal plane shutter, and extinction meter. The upgraded shutter boasted an ambitious top speed of 1/1250 which tied the Zeiss-Ikon Contax for the fastest available cloth focal plane shutter in the world.

It seems that Candid took a few cues from both the Zeiss Contax (top 1/1250 shutter speed and long base rangefinder) and combined it with some features from the Leica III (horizontally traveling cloth focal plane shutter and screw lens mount). Nippon Kogaku would take a similar approach a decade later with their first Nikon rangefinder, by borrowing what they liked from the two cameras and making their own.

The later Perfex cameras would resume production after World War II and for a while, it would seem the company made an effort to stay competitive, but it didn’t last long. The general poor reputation of most small American built cameras doomed the Perfex series to become bargain-bin cameras, and that resulted in a dramatic cheapening of the camera.

Later Perfex cameras would lose both the cloth focal plane shutter and interchangeable lens mount, replaced with a Wollensak leaf shutter and fixed lenses. The cast metal body was also replaced, in favor of one made of sheet metal. The last Perfex cameras would be released in 1950 at which time the Candid Camera Corporation sold their remaining camera designs to Ciro, who would later sell them once again to Graflex.

Today, unless you have a particular affinity for American cameras, Perfex cameras aren’t very collectible. The Speed Candid was poorly build and hard to use, but therein lies it’s charm. If you’re the kind of person who likes adding oddball cameras that look like no other to your collection, then this is one camera that would be right up your alley.

Repairs

The Perfex Speed Candid came to me with a working shutter, but the rangefinder didn’t move at all. Being an uncoupled design meant that the rangefinder is in it’s own separate compartment so I thought it should be pretty simple to get working again.

Gaining access to the rangefinder is just a matter of removing the three screws on the top plate of the rangefinder, and once the top is off you have access to everything you’d need to get it going again.

Gaining access to the rangefinder is just a matter of removing the three screws on the top plate of the rangefinder, and once the top is off you have access to everything you’d need to get it going again.

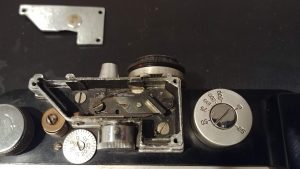

Uncoupled rangefinders do not have any linkages to the lens to detect the focus distance of the lens, and since this is a split image type, there’s no beam splitters or any type of prisms needed to split an image into two halves. There is simply 2 windows, two mirrors and a moving arm and that’s all.

With the top off, I could clearly see that whatever lubricants were used in this camera over 80 years ago had simply hardened and nothing was moving. I removed all visible screws, paying attention to how they went together, and cleaned everything up with some naphtha oil. I used glass cleaner to clean the mirrors and inside of the windows and put it back together. Although the mirrors moved, they weren’t exactly smooth, so I took it all apart again and put a dollop of white lithium grease on two pivot points, as seen in the image to the right.

With the top off, I could clearly see that whatever lubricants were used in this camera over 80 years ago had simply hardened and nothing was moving. I removed all visible screws, paying attention to how they went together, and cleaned everything up with some naphtha oil. I used glass cleaner to clean the mirrors and inside of the windows and put it back together. Although the mirrors moved, they weren’t exactly smooth, so I took it all apart again and put a dollop of white lithium grease on two pivot points, as seen in the image to the right.

With everything back together, I noticed that the rangefinder mostly worked. I could get it to line up at infinity with a utility pole across the street from my house, but I noticed that as I used it, the rangefinder still stuttered at close focus. At this point, I stopped messing with it, as I never really expected the rangefinder to be that useful on this camera anyway. My plan was to use the camera as scale focus and not rely on the rangefinder.

The failure of the rangefinder to work correctly is clearly a result of it’s rudimentary design. While it’s certainly understandable that something might not work the way it was designed nearly a century ago, everything in here was so cheaply made, I have a sneaking suspicion it never worked right. I have to imagine that a large number, if not all, of these cameras had issues right off the assembly line. Very few of these cameras were ever sold and even among American rangefinders, there were better options such as the Argus C3 at the same price point that worked much better.

My Thoughts

The Perfex Speed Candid is not an elegant camera. I knew it was ugly just by looking at photos I saw of it online, but once I had the opportunity to handle one, I was not prepared for how unexpectedly large and ungainly the whole thing would look in person. There are those who scoff at the brick-like dimensions of the Argus C3, but where that camera is utilitarian and purposeful, the Speed Candid is…well…just look at it!

That’s not to say the camera still doesn’t have a bit of charm. The large Phillips screw heads on the front plate, the crudely die cast parts of the top rangefinder, and the (obviously stolen from the Argus A series) lines in the curved black Bakelite body look like no other camera ever made.

The camera is comically large and heavy. Despite shooting the same kind of film as the also heavy Argus C3, the Perfex is significantly larger and weighs 810 grams. That’s nearly 1.8 lbs, and considering a large part of the body is made of Bakelite, imagine if that was all steel or brass! The rear door of the camera isn’t a thin piece of tin like on the Argus, it’s a solid piece of metal that adds another 101 grams to the weight of the camera.

The top plate of the camera is very cluttered and disorganized with pieces of the camera seemingly haphazardly placed in their locations with little regard to ergonomics.

Things get started rather inconspicuously with the normal looking rewind knob on the left but get strange quickly with the brass disc and exposed spring thing next to the rangefinder. This “thing” is the release for the film catch, which stops the film from advancing at the end of each exposure. It also functions as the rewind button when you’ve reached the end of a roll of film. You need to press and hold it while turning the rewind knob on the bottom of the camera.

The Argus C3 has a similar film catch that must be pressed before you can advance the film to the next frame or rewind the camera. In looking at other Perfex Speed Candids online, none of them had a film catch that looks like this, so I am assuming this is a custom repair that someone fabricated at some point in the past. Although there aren’t many images of speed Candids that show the back or top, from what I’ve seen, this catch is usually much smaller and chrome plated, rather than exposed brass like this.

Moving on, we have the exposure counter which is nothing more than an exposed disc with numbers from 0 – 35. Like the Argus C3, this counter needs to be manually reset and counts upwards starting at 0. See that small flat head screw next to it? That screw is the indicator for the exposure counter and doesn’t actually connect to anything inside of the camera.

From the back of the rangefinder we see the distance scale for the rangefinder. The Perfex Speed Candid has an uncoupled rangefinder, which means you take a distance reading by turning this knob and peering through the rangefinder window which shows a split image. When the two halves of the image line up, you look at what distance is on the chrome plated knob and transfer that to the lens. It’s not elegant, but it works, at least in theory as despite my attempts to get this rangefinder working, I couldn’t ever get it to be accurate.

Next to the rangefinder we have the shutter speed knob that also doubles as the shutter cocking knob. This knob’s close position to the rangefinder makes it uncomfortable to grip and it has a pretty strong spring load on it from the shutter which means that it wants to slip out of your hands while turning it, so caution must be made to properly rotate it a complete three quarter turn without slipping, to fully cock the shutter after each shot. Conveniently, there are two dots on the center shaft of the knob that show the selected shutter speed both before and after cocking it. To change speeds, you lift up on the outer ring and rotate it until the desired speed is next to the correct dot (depending on if the shutter is cocked or not). I think at one time, one of these dots was red and one black, but on mine, both were black.

Finally, we have the straight through viewfinder piece. As you might expect, there is nothing inside of the viewfinder to indicate anything about the camera’s status. I did not care for the extreme right handed orientation of the viewfinder as this was not a natural way for me to hold a camera and look through it’s viewfinder, but at the very least, it was decently large and easy to compose with.

The back of the camera, as mentioned before, is a large slab of metal, held on by two spring loaded retaining clips. Initially, I had some concerns over the light sealing properties of this door, but with deep recesses and no ability to bend the metal, I was reasonably confident it would do its job.

Speaking of jobs, the back door has an elaborate circular exposure calculator that seems to have been common on American cameras of the era. We’ve seen similar style calculators on the Argus CC, Universal Mercurys I and II, and the Detrola series. Like those cameras, the calculator is overly complicated and requires moving a very small disc to match up film speed with an arbitrary number seen through the extinction meter on the bottom of the camera to get appropriate shutter speed and aperture readings.

The extinction meter is seen through the small rectangular window on the bottom of the camera. Extinction meters were an early type of exposure meter that would have a series of numbers or letters on a semi transparent piece of film. The film would progressively get darker from one side to the other and the idea is that you could take a light measurement by reading the last number (or letter) that you could see before it gets too dark.

In the case of the Perfex, there are numbers from 1 to 32 that move from lightest to darkest, right to left. In the image to the right, I have the meter pointed right at the sky and the number 32 is barely visible, so I would use that reading using the exposure calculator. If the light wasn’t quite as bright, I would only be able to see 16, or even 8.

On the underside of the camera is the film advance knob, hump for the extinction meter, and right mounted 1/4″ tripod socket. I never like seeing tripod sockets on heavy cameras like this on the side as the camera’s weight will continually put pressure on the body, increasing the chance of damage, but let’s be honest. How many times do you think Perfex Speed Candids were ever used on a tripod?

Removing the back of the camera requires pressing outward on the two clips on the back of the camera, and the entire door comes off.

The film compartment is rather crude, but functional. Film transport is from right to left, and loads onto a fixed and slotted take up spool. The cloth curtains on this camera are in surprisingly good condition and don’t show any immediate signs of holes or cracks in them. What’s really interesting to me is that the film compartment really shows the scale of how much wasted space there is on this camera. The Perfex Speed Candid is not a complicated design. There is a lot of wasted horizontal and vertical space in the camera that becomes evident when looking at the back of it.

The front of the camera has the left handed shutter release button in a similar location as to where you’d find it on an Exakta camera. If you look closely, there are screw threads around the base of the shutter release which are there to accommodate a metal cap that screws on over the shutter release which has a threaded hole in it for a shutter release cable. Without this cap, there is no other way to attach a shutter release cable to the camera.

The lens mount is a typical screw in type, but is somewhere around 38mm or possibly even 1.5 inches which would make sense since nothing on the camera is measured using the metric system. Although the lens mount is physically the same between later Perfex cameras, the later lenses cannot be used on the Speed Candid as they have a fixed focus ring and rely on an in body helix on the later cameras, which is absent on the Speed Candid. They’ll physically mount, but you won’t be able to change focus.

I tried to mount the Graf Perfex Anastigmat lens to a Canon rangefinder and the Perfex lens was just barely smaller than the M39 mount and went entirely into the camera without engaging the threads. American companies like Perfex couldn’t have used the Leica Thread Mount because prior to the war, Leitz had a patent on the 39mm screw mount. This would later be voided after the war, but many pre-war manufacturers still avoided using a screw mount with these exact dimensions for this reason.

The Speed Candid was an ambitious camera by a company with no experience making cameras. They managed to include quite a feature set in a camera at an affordable price, but I can’t help but wonder why many of the various design choices were made. There were other 35mm cameras at the time of the Speed Candid’s introduction which could have been used as a reference for good design, and there a few areas in which Candid clearly borrowed from neighboring Michigan’s Argus A-series, which is discussed on the Speed Candid page at Scott’s Photographica Colleciton, but clearly, they did not borrow enough. Despite the camera’s many strange quirks, what is it like to shoot one?

My Results

Back in the summer of 2018, I came across an unopened 100′ roll of Kodak Vision3 50 cinema film. This type of film has a protective layer on it called Remjet which is supposed to protect the film as it travels through a cinema camera. The Remjet has no effect on the emulsion side of the film, but must be removed during the development process, otherwise it can sludge up your chemicals and makes the film unscannable.

I found a couple home remedies involving baking soda so I thought I’d give it a try, but the results were poor. I didn’t get all of the Remjet off, and the images came out pretty bad, so I set the film aside with the intent on giving it another go at some point in the future.

This past winter, as I was growing tired of black and white, I thought I should try the Vision3 again, so I rolled some into an empty cassette and loaded it into the Perfex Speed Candid. I did not have a lot of confidence that the camera was working, so I figured if the film turned out to be a bust again, it was no big loss. I quickly shot about 30 exposures in late February 2019 and hoped for the best.

I was quite impressed with the performance of the Perfex and it’s Graf Perfex Anastigmat lens. My choice of Kodak Vision 50D film was a wise one as the warmer tones of the film complimented the uncoated optics quite nicely.

Image sharpness is on par with other quality triplets of the era across the frame and I noticed little to no vignetting near the corners, which might actually be seen as a disappointment as many people tend to like these types of artifacts in vintage cameras. There did seem to be an issue with film flatness however, that resulted in several images where the center is out of focus, but the edges were sharp.

After seeing these results, I examined the camera, paying close attention to the film pressure plate and saw nothing wrong. I’ll have to do some further investigation to see why this happened, but overall, I was very happy with the images the camera made.

Using the camera is a slow process, not only is it an ergonomic travesty, but the combined shutter speed and shutter cocking knob is too close to the rangefinder to comfortably grip and has a strong spring that constantly wants to slip out of your hand. Even after cocking the shutter, you have to remember to advance the film using the advance knob on the bottom of the camera or else you risk double exposing your previous shot. Finally, the rangefinder is almost completely useless. Although the one on this example needed repair, looking at the design, I can’t see how it ever would have worked, even when new.

I can forgive technical deficiencies like film flatness and some pinhole light leaks for an 80 year old camera, and at least say that in good working order, the Speed Candid would have been quite a capable camera, but what I can’t forgive is it’s horrible ergonomics. For anyone who lambastes the Argus C-series for it’s brick-like appearance, know that it could have been much worse. Where the Argus is just strange but can easily be overcome with a little bit of patience, I’d argue no one ever, in the history of the world, has, or would ever get over the design choices made with this camera.

But of course, therein lies it’s charm. This is a grotesque and copious camera with a surprising number of features. When you look at it from a value perspective, at a price costing equal to a week’s worth of work in 1938, a working American family could have a capable system camera with a rangefinder, exposure meter, focal plane shutter, and interchangeable lenses. It’s not pretty for sure, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and I guess to the right person, this ugly duckling could…oh what the hell am I saying. This is an ugly camera that was cheap when it first went on sale, but despite its poor ergonomics, could still make some pretty decent pictures. There, I said it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.vintagephoto.tv/speedcandid.shtml

https://www.cameraquest.com/perfex.htm

http://www.brennanprobst.com/2013/05/spotlight-perfex-speed-candid.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/perfex-speed-candid-in-need-of-love.203228/

What a find: A Perfex bakelite brick with an uncracked, unchipped, light-tight body. One this nice rarely shows up on That Popular Auction Site. Thanks for this review, as I’ve wondered if the lens was worth shooting. And kudos for the 4th of July fireworks webpage motif!

I have 2 of the perfex speed candid cameras in the original cases and with original instruction manuals not to mention about 7 other old cameras and video cameras. But I am having a hard time figuring out what the two are really worth.. I seen 1 on eBay for 6.000 but I’m very skeptical that , that is a realistic price.. I was wondering if u might be able to help me. Know what they are actually worth. Thank you.

Laken

Lalen, I am not a good resource for camera appraisal as I can only tell you what I paid for mine. I picked up my Perfex Speed Candid with case, but no manual for $20 last summer. I’ve never seen them sell for over $50.

One error, the shutter winding knob doesn’t advance the film. That’s the knob on the other end next next to the wind release button. so every shot you have to wind two knobs, one while you push the button. It makes an Argus C3 seem easy to use. I recently found one where the shutter kinda works. But there’s a gap between the curtains when you rewind them, so a lens cap needs to be used when the shutter is wound. That and some cracks and a chunk out of the body I need to tape up, but I’m determined to get some images out of it.

Doh! You’ve unveiled a flaw in my process where I can often shoot a camera and not create the review for it until months, sometimes even years later and I forget details like that. I’ve fixed the review and added a paragraph near the end of the review talking about how terrible of a design this is. Thanks for the correction, Eric! 🙂