This is the Asahi Pentax, the very first 35mm SLR produced by the Asahi Optical Company of Japan to use a pentaprism viewfinder. The camera is often referred to as the Pentax AP by collectors even though that was never officially documented. The other camera is the Asahi Pentax K, the second variant of the camera produced in 1958 which upgrades the camera with a semi automatic diaphragm. Both the Asahi Pentax and Pentax K were hand built cameras produced in Japan and are sought after by collectors not only for their history, but their looks and performance. Some would say, these are the most beautiful SLR cameras ever produced in Japan.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 55mm f/1.8 and f/2.2 Asahi Takumar coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount

Focus: Variable

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, (AP) 1 – 1/500 seconds, (K) 1 – 1/1000

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: PC Port FP and X Flash Sync

Weight: (AP w/ lens and body only) 726 g / 577 g (K w/ lens and body only) 761 g / 585 g

Manual (AP): http://www.cameramanuals.org/pentax_pdf/asahi_pentax.pdf

Manual (K): http://www.cameramanuals.org/pentax_pdf/asahi_pentax_k.pdf

How these ratings work |

The original Pentax models, AP and K, are two of the most elegantly designed cameras ever made. They were built with an extreme attention to detail, and no expense was spared in their construction. The control layout of these cameras was so perfect when first introduced, that Asahi Optical Co, had to do very little over the next 2+ decades of camera design. Whether you are a shooter or a collector, having an early Pentax in your collection is a must! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.3 | ||||||

Asahi and Pentax are two names that long have been associated with some of the best optical products Japan has ever made. Originally founded by Kumao Kajiwara in Toshima, Japan, a suburb of Tokyo in November 1919 as Asahi Kōgaku Goshi Kaisha, (Asahi Optical Joint Stock Co.), the company produced a variety of lenses and other optical products for the burgeoning Japanese optical industry. The use of the word “Asahi” in it’s name was a common theme among Japanese companies as Asahi loosely translates to “morning sunrise” which was a symbol of the Japanese people, and was the inspiration for the red circle on the Japanese flag. There were even other optical companies that used the name “Asahi” such as Asahi Bussan G.K. who distributed a series of unrelated Olympic cameras in the 1930s.

Asahi Kōgaku Goshi Kaisha’s earliest products were lenses for eyeglasses, which gave them quite a lot of experience in the cutting and polishing of optical glass. With this skill, in 1923 they expanded their portfolio to projection lenses, binoculars, and other scopes. Early Asahi products were sold under the brand name “AOCO” which likely is an abbreviation for Asahi Optical COmpany. The “AOCO” logo would continue to be used on Pentax products throughout a large portion of the 20th century.

Quickly establishing themselves as a skilled maker of lenses, in the 1930s Asahi expanded once again into the market of camera and photographic lenses. Asahi’s photographic lenses were not sold under their own name, but rather under the names Zion and Optor which were produced for other Japanese companies like Konishiroku and Molta, who would both later become Konica and Minolta, respectively.

It is unclear whether Asahi designed the lenses, or just manufactured them to the specifications of their customers, but whatever the case, their previous abilities with eyeglasses and projection lenses gave them ample capacity and speed to make the lenses quickly, allowing both Konica and Minolta to establish themselves in Japan’s early camera industry.

In 1938, company founder Kumao Kajiwara passed away and an Asahi employee named Saburo Matsumoto took over. The company was reorganized by the Japanese government and it’s name was changed to Asahi Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. and it produced optical products for the Japanese military up through the end of the war.

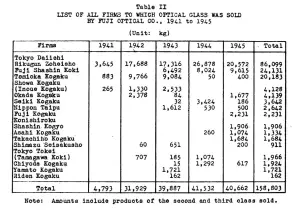

There is little information about Asahi’s exact role during this time. Did they produce lenses used in the assembly of military products by other companies, or did they supply complete optical assemblies such as binoculars or other kinds of scopes. Further confusing it’s role during the war was that in a study by the US Navy in August 1945 of Japan’s optics industries, it was found that Asahi Kogaku was a purchaser of glass produced by Fuji between 1943 and 1945. Why Asahi would purchase glass from another Japanese company is not clear, and perhaps is a but a small piece of a puzzle with no clear answer.

By the end of the war, nearly all of Asahi’s factories in Japan were destroyed, and the company was forced to close, but only for a short time. In 1948 (some sites suggest 1946, but I believe 1948 to be correct), Saburo Matsumoto was able to convince the occupying American forces to help re-establish the company in a new factory, this time as Asahi Optical Company, Ltd.

Like other Japanese optical companies of the late 1940s like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), Seiki Kogaku (Canon), and several others, Asahi was required to produce optical products exclusively for export. Their first product was a telescope, produced in the spring of 1948 made specifically for viewing a total eclipse of the sun in Japan that year. The telescope was made out of cardboard but used Asahi’s high quality lenses and was quite popular. Later that year, they released a set of Jupiter binoculars which were of much higher quality and helped to establish Asahi as a worthy competitor in the Japanese optical market.

With the company on a roll, Matsumoto wanted to expand into photographic cameras and sensing a crowded market of German rangefinder cameras and other Japanese companies who were copying their designs, in 1949 he decided to pursue a Single Lens Reflex design.

The earliest Asahi SLR designs were not successful, and forced Matsumoto to reach out to his colleague Ryohei Suzuki who he had met while producing lenses for Konishiroku and asked if he would help build an all new 35mm SLR. Intrigued by the idea, but lacking in camera making experience, Suzuki contacted his friend Nobuyuki Yoshida who had the necessary experience working for Konishiroku and also as an independent camera repairman.

With Suzuki and Yoshida on board, Matsumoto had the team he would need to build his new camera and in a few short months, the first Asahiflex prototype was built. The camera was designed entirely from scratch and did not copy from any existing 35mm SLR. It is said that the only reference for what an SLR should be came from an old Reflex-Korelle 6×6 SLR that Matsumoto had from before the war. Although 35mm SLRs like the Kine Exakta and Zeiss-Ikon Contax SLR did exist at the time, they were not exported to Japan so were not available for inspiration.

The earliest designs for the Asahiflex were completed in November 1949 and three working prototypes were finished in October 1951, which is an incredibly fast turnaround for designing a new camera from the ground up, especially one by a company with no prior camera making experience. The camera was called the Asahiflex, taking the name of the company and adding -flex to the end, which was a popular naming convention for reflex cameras of the time.

Upon seeing the finished camera and some sample images made from it, Saburo Matsumoto was very excited about his new camera and began to market it immediately. Initial reception was lukewarm however, as the SLR market had not yet grown as rangefinders were still the preferred choice by professional and semi-professional photographers.

Matsumoto was persistent however and eventually gained interest from the optical division of Hattori Tokeiten K.K. (predecessor to Seiko) who agreed to distribute the camera. Production models first went on sale in February 1952 at a rate of about 200 units per month, but quickly expanded to 500 per month, a very good number for a unique camera made by a small Japanese company.

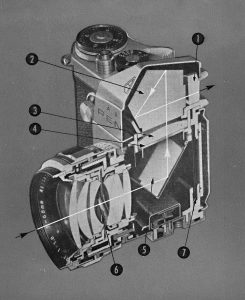

The Asahiflex was an interesting camera as it contained both a non-removable waist level reflex finder along with an eye level viewfinder on the body of the camera. This second viewfinder was fixed at 50mm and allowed the photographer to quickly frame their image without it being reversed as was the case of all waist level viewfinders.

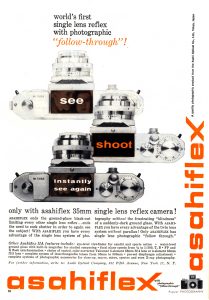

The Asahiflex had a modern (for the time) feature where the reflex mirror was coupled to the shutter release. When the photographer would press the shutter release, the mirror would flip up and remain in the up position for as long as the shutter release was held down. Upon releasing the shutter release, the mirror would return to the down position. This quick, but not instant return mirror was pretty significant for the time as most SLRs of the era had a mirror that would only return to its position when the shutter was cocked. Two years later in 1954, the Asahiflex IIb was released which had a true instant-return mirror where the mirror would return to the down position immediately after the shutter closed, regardless if the photographer was still holding down the shutter release.

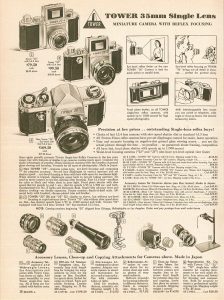

Although the Asahiflex was exclusively marketed in Japan, there were some export models sold in the United States by the Sears Roebuck Co, under the names Tower Model 23 and Tower Model 24.

By the mid 1950s, more and more German SLRs featured a pentaprism viewfinder which did not invert the image like on a waist level viewfinder. The first German SLR with this feature was the Contax S released by Zeiss-Ikon in 1949, but prototypes existed from before the war. The need for such a feature was not lost on Saburo Matsumoto, so in 1954 he demanded that a pentaprism version of the Asahiflex be created.

The first Pentaprism Asahiflex was shown in the December 1954 issue of the Japanese magazine “Shashin Salon” and featured a bulky black pentaprism, affixed to the top of an Asahiflex IIA body. In the image seen above, the pentaprism looks like it might have been removable which would have been consistent with most other SLRs of the day. The bulky prism made the camera appear top heavy, so thankfully this was a short lived design as a later prototype was produced which much more closely resembled what would become the first Asahi Pentax.

Both prototype cameras eliminated the optical viewfinder from the top plate, allowing for a larger, and easier to grip rewind knob, with integrated film reminder dial. Both cameras also retained the original Asahiflex’s 37mm screw mount. Since there was no established method for mass producing the glass pentaprisms required to make the viewfinder work, all early pentaprisms were made by hand, which was very costly to make.

In 1957, Asahi Optical released their first pentaprism SLR which they called the Asahi Pentax. Ironically, Zeiss-Ikon owned a trademark on the name ‘Pentax’ which was an amalgam of PENtaprism and ConTAX although they never used this name in any marketing materials. Asahi acquired the rights to the name Pentax in most markets prior to releasing their new camera.

Although Asahi beat both Nikon and Canon to the market with their pentaprism SLR by 2 years, they were not the first Japanese camera company to release a pentaprism SLR. This honor went to Orion Seiki Sangyō Y.K. with their Orion T, later known as the Miranda, which debuted in 1955. Since Miranda no longer exists today, this makes Pentax the longest running brand of Japanese SLRs still in production.

When the Asahi Pentax was released, it wasn’t a revolutionary design compared to German SLRs of the era, but it did refine the design into a more compact body that was affordable and easy to use making it immediately popular all over the world. New features included a rapid wind film advance lever, a fold out rewind knob, a dedicated 1/50 flash sync speed, larger and easier to use strap lugs, and perhaps most significantly, was the addition of the M42 screw mount, commonly used by many popular German companies such as Zeiss-Ikon and KW, giving the Pentax a huge variety of lenses to choose from.

Here are some of the highlights of the original Asahi Pentax design which were either firsts in the industry, or just really uncommon.

- The camera body weighed 577 grams which was about 250-300 grams lighter than other SLRs of the era.

- A rapid wind lever as opposed to a knob like on other SLRs.

- Fold out film rewind crank for rewinding the film back into the canister.

- A Fresnel focusing screen which made the viewfinder very bright and easy to use.

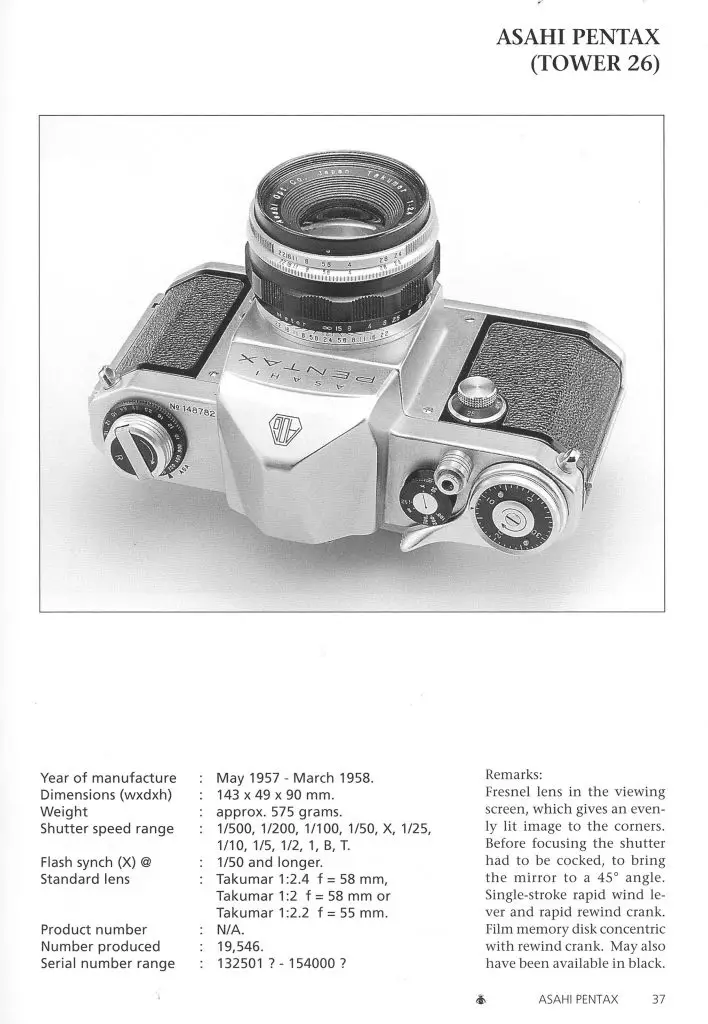

In addition to these conveniences, the locations of many of the controls on the original Asahi Pentax were so popular that they set the standard for control layout of SLRs for decades to come. The Pentax AP sold well, especially considering Asahi Pentax was still relatively unknown throughout the world. A total of 19,546 Pentax APs were produced between May 1957 and March 1958.

Fun Fact: Asahi didn’t distribute their cameras to the United States directly, rather they had an arrangement with the American department store chain, Sears Roebuck & Co, to sell rebadged versions of their cameras in their stores and catalogs. Sears sold earlier Tower models which were rebadged Asahiflex models, and the Tower 26 which was a rebadged Pentax AP. The catalog page to the right shows three models for sale from the Sears 1957 camera catalog.

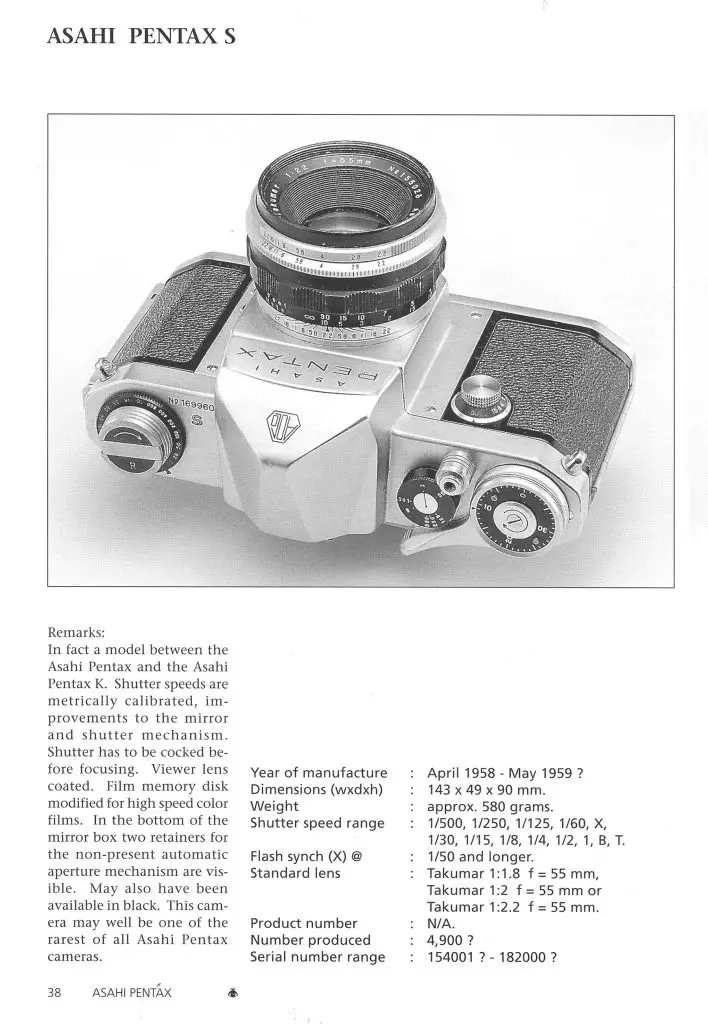

The camera industry moved very quickly in the mid to late 1950s and most companies had to make continual improvements to their designs to stay relevant and the Asahi Pentax was no different. In April 1958, a mere 11 months after the original model’s release, a revised version called the Pentax S was released which changed the available shutter speeds to a more arithmetic scale, gone were speeds like 25, 50, and 100, and in their place was 30, 60, and 125. With the release of the Pentax S also came a new lens, the Takumar 55mm f/1.8.

A few other less obvious changes were the rear viewfinder glass received a coating to improve contrast, and the film reminder dial supported a wider range of films. The Pentax S was produced for a very short period of time with less than 5000 thought to have been built, making them one of the rarest of the early Pentaxes.

The gallery below shows three pages covering the three original Pentaxes from The Ultimate Asahi Pentax Screw Mount Guide by Gerjan van Oosten.

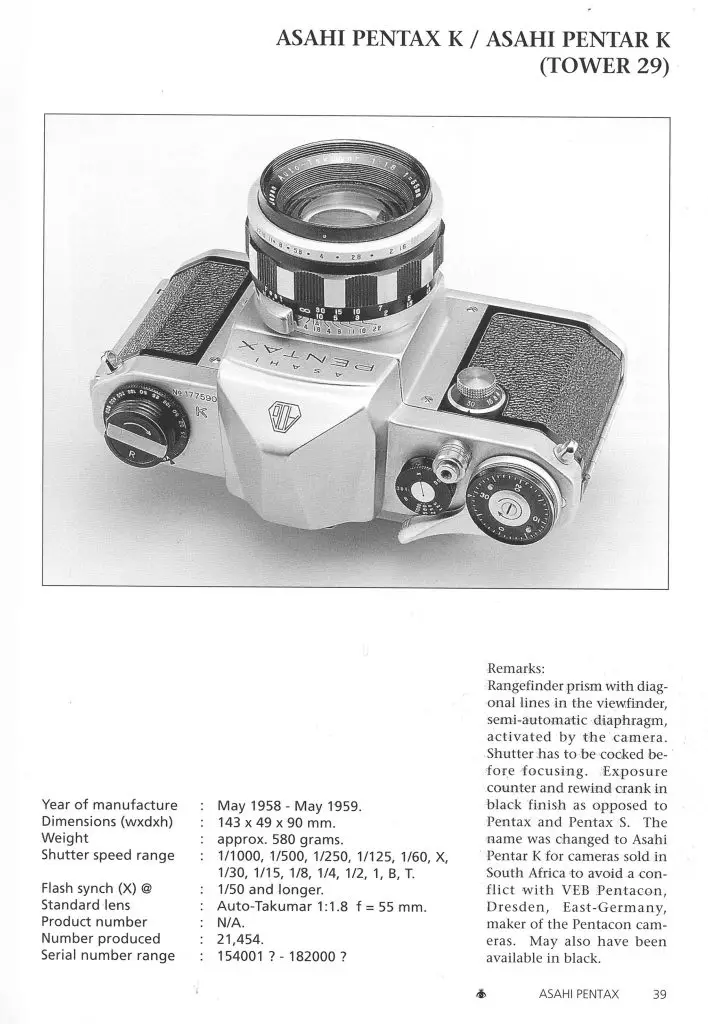

The reason for the short run of the Pentax S was because a significantly updated model would be released in May 1958, only one month after the Pentax S made it’s debut. This new model was called the Pentax K. At least one site suggests that “K” was short for “King of the SLRs”, but I am unsure if this is just a fun urban legend or if it’s based on facts. Both the Pentax S and K were sold at the same time, the “S” being a more economical choice.

The Pentax K had a number of changes. The most significant being support for lenses with semi and fully automatic diaphragms. When combined with the semi-automatic Auto-Takumar 55mm f/1.8 lens initially offered for the camera, for the first time, the photographer could focus and compose their image with the lens wide open, regardless of which f/stop is selected on the lens. Upon pressing the shutter release, the iris would stop down to the chosen setting moments before the shutter fires.

Being semi-automatic however, means that this whole process requires an extra step of activating a cocking lever on the lens to open the iris prior to each shot. Without activating this lever, the lens remains stopped down until it is opened again. This semi-automatic design had been in use by other manufacturers like Zeiss and Yashica who had semi-automatic lenses as well. Whether it was a coincidence or not, the design of an external lever for manually opening the iris on the semi-automatic Takumars is very similar to the one used by Yashica with their semi-automatic Yashinon lenses of the same era.

A cool thing about the way the automatic diaphragm worked on the Pentax K means that it is compatible with fully automatic lenses that would come later. If you take a Pentax K and mount a later Auto-Takumar lens, the camera functions with the fully automatic diaphragm as normal.

Other upgrades to the Pentax K were:

- The top shutter speed has been increased from 1/500 to 1/1000

- Microprism focusing aide added to viewing screen

- Exposure counter and rewind crank are trimmed in black instead of silver

- Name changed for cameras sold in South Africa to Pentar K to avoid trademark dispute with VEB Pentacon

With the release of each of these three models, there was much to be excited about in the photographic press. In a test report in the January 1958 issue of Modern Photography, author Myron A. Matzkin had nothing but praise for the camera. Although the original AP wasn’t the first camera with an instant return mirror, it’s inclusion in this new model combined with a bright pentaprism viewfinder was exciting stuff.

With the release of each of these three models, there was much to be excited about in the photographic press. In a test report in the January 1958 issue of Modern Photography, author Myron A. Matzkin had nothing but praise for the camera. Although the original AP wasn’t the first camera with an instant return mirror, it’s inclusion in this new model combined with a bright pentaprism viewfinder was exciting stuff.

Period advertisements for the camera proclaimed the Pentax to “End Photographic Blackout”. The build quality, bright viewfinder, quiet shutter, and lightweight aluminum body all received accolades as well, making for an extremely capable camera from this small Japanese manufacturer. When it first went on sale, the Pentax AP sold with a Takumar 55mm f/2.2 lens for $195. The Pentax K increased the price to $249.50 with the Auto-Takumar 55mm f/1.8 which when adjusted for inflation compares to $1725 and $2200 today.

By 1959, the Asahi Pentax went from a curious new camera from a small Japanese company to a major player in the 35mm segment. Not only was the camera designed from the very beginning to have the latest technology and a classic and timeless design, but the company continually updated the camera. For as great as the Pentax K was, in 1959, a new model called the Pentax S2 made it’s debut which eliminated the front mounted slow speed dial, instead featuring a single shutter speed dial with all speeds. Another improvement to the shutter speed dial is that it did not rotate while the shutter was firing which eliminated shutter timing issues due to a finger coming in contact with it while moving.

Throughout the rest of the 1960s, Asahi would continue to expand it’s products, releasing new models almost every year. The Pentax S-series would continue on through 1968, at which time it was replaced by the Spotmatic which made it’s debut in 1964.

An interesting observation about Asahi is that they clearly valued evolution over revolution as each new model, even those with significant upgrades, did not stray far from the original formula. If you look at the very first Asahi Pentax AP from 1957 and compare it to the last Spotmatic from 1976 and there are obvious cosmetic similarities. Even the later Pentax K-series which started with the K1000 in 1976 retained many of the design cues from that original model. Asahi found a formula that worked and stuck with it.

Today, nearly every screw mount Pentax SLR is respected among collectors and shooters alike. These were well built cameras that are compact and easy to use, and support a huge variety of excellent screw mount lenses. The original models, the Pentax AP, S, and K in particular are highly collectible, not just for their history, but that they are gorgeous looking cameras. The earlier models were mostly built by hand and not by automation, giving them an extra level of perceived “quality”. Whether that quality is real or just in people’s heads is anyone’s guess, but no one will doubt that these early cameras aren’t precision devices.

My Thoughts

I wrote my first review of a classic Pentax SLR back in April 2015 for the Pentax Sv, a camera that debuted barely 5 years after the original Pentax AP. In that review I gave positive comments on the feel, ergonomics, and layout of that camera, proclaiming it to be one of my all time favorite cameras, an opinion I still hold true today. In my mind, these early Pentax SLRs represent a perfect balance of early Japanese build quality, without having the large and heavy size of other SLRs of the day.

What’s so great about these early Pentax SLRs is how close to a perfect design Asahi got on the first try. It does not matter if you’re picking up the original Pentax AP, or a Spotmatic SP, or a K1000, the cameras are instantly usable with every control exactly where you expect it to be. I have a theory that Pentax SLR manuals were the least read camera manuals ever made, because no one ever needs to read them.

Other than the presence of the letter “K” beneath the serial number and the from chrome to black on the dials, there is no functional difference between the Pentax AP and K. The pop up rewind knob is on the left with a film reminder dial beneath it. The large pentaprism occupies the center with the rotating shutter speed dial with speeds from 25 – 500 on the AP and 30 – 1000 on the K, plus Bulb. To shoot slow speeds on either camera, you must have the shutter speed selector at the slowest speed, whcih then activates the slow speed dial on the front of the camera, just like a Leica III. Finally, to the right is the rapid film advance lever with integrated, non-manually resetting exposure counter on top. The rapid wind lever on these early Pentaxes is elegantly sculptured with a beautiful (dare I say ‘sexy’) curve to it. It is perhaps the most perfect rapid wind lever I have ever seen on a camera.

The bottom of both cameras is exactly the same with the rewind release button on the left and a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket. The socket is part of the main body of the camera, and not the bottom plate like on lesser cameras, which means it has more strength for balancing on a tripod with a heavy lens without any chance of flexing.

Both cameras have a sliding release lock on the camera’s right side for opening the film compartment. The Pentax AP and K both predate the use of foam light seals, so no replacement was necessary on these cameras like would have been the case on later models.

The right hinged film compartment is like the rest of the camera in that Asahi got everything right on the first try. There were certainly other 35mm SLRs prior to the AP, but it’s refreshing to see a film compartment that looks just as normal in 1957 as it would have decades later. Film transport is from left to right onto a fixed take up spool. The film pressure plate has divots on it which helps reduce friction as the film passes over it, allowing for a smoother film transport.

Early Pentax SLRs famously used the M42 screw mount which at the time was more commonly known as the Praktica mount, named after the East German Praktica camera who made the mount famous in the very early 1950s. While it was pretty common for Japanese companies to release new lens mounts for their new SLRs, Asahi wisely went with a mount that was already established in the market, which meant that photographers with existing Praktica lenses could try them out on a Pentax body.

In my opinion, this was the reason that Pentax SLRs caught on so well, whereas some other early Japanese SLRs like those made by Miranda (Orion) and Topcon (Tokyo Kogaku) didn’t. In 1957, there were still quite a number of people who were suspicious of the quality of Japanese made products. Nikon and Canon products were helping to break that reputation, but they didn’t make SLRs, and their rangefinders were expensive and out of reach of the amateur or students who might have been in the market for a new SLR.

From the outside, there is little to differentiate the AP to the K other than some minor cosmetic changes. By far, the biggest difference was support for lenses with an automatic diaphragm, or iris. A revised mirror box added a hinged metal plate that would push on a pin on “Auto-Takumar” lenses moments before the shutter would release, which would stop down the iris on the lens, allowing the photographer to compose their image with the lens wide open and only stop down for exposure.

The original Auto-Takumar lenses available for the Pentax K was of a semi-automatic design in which an externally mounted lever must be pressed down before exposure, “cocking” the lens and opening the iris. A variety of semi-automatic Takumars were available with focal lengths from 35mm to 135mm. Later Auto-Takumar lenses were fully automatic, which eliminates the need for this lever. Conveniently, the Pentax K is forward compatible with fully-automatic Takumars as the release pins on those lenses could be actuated by the one in the Pentax K.

Another improvement with the Pentax AP and K from earlier SLRs was the inclusion of a Fresnel focusing screen that improved brightness across the viewfinder, especially at the corners. In the center of the Pentax K’s viewfinder is a very large microprism circle, surrounded by a frosted ground glass outer circle. The Pentax AP has the same exact viewfinder, except it lacks the microprism circle and only had a large ground glass circle. The microprism circle is different from others I’ve seen in that the microprisms are very small and do not have the “diamond” pattern often seen on other cameras. I found this circle to be very easy to compose with. Compared to other SLRs of the day, the viewfinder is not only bright, but very easy to use.

There’s really not a lot to not like about either the Pentax AP or K. These were very well built cameras with excellent ergonomics, perfect balance, a bright and easy to use viewfinder, and of course a huge selection of excellent lenses available for them. Whether or not you use one of Asahi’s Takumar lenses or a German screw mount lens, you’d have to really try to not get a great image from one. So with that in mind, how hard did I try?

My Results

Sadly, the shutter on the Pentax AP was inoperable so I was unable to shoot it, but the Pentax K worked perfectly so I put two rolls of film through it. The first was my old standby, Fuji 200, but the other was a 14 year expired AGFA HDC Plus 200. I shot the images below over the course of the summer of 2019 around the house and on trips to Brookfield Zoo and downtown Chicago.

This isn’t a film review, but I must say how impressed I was with the AGFA HDC film. After seeing the scans, I had to check the box to confirm that this film expired in 2006 as the colors were nearly spot on. I had been shooting some fresh Kodak Pro Image 100 recently and had to check the rebate info on the film to confirm that this was the AGFA. What a wonderful film and it’s ability to withstand nearly a decade and half of age and still look as good as it did, is remarkable.

It’s probably good that I had such great comments to say about the film as the Pentax delivered as good as I had hoped. I have extensive experience with Asaki Takumar lenses, having shot them on a variety of Pentax and non-Pentax screw mount bodies. I’ve shot them on the Pentacon FM, Zenit E, Wirgin Edixa Reflex, and the Chinon Memotron all with great results. The only question was whether the reputation of their optics was just as good with this earlier 1950s camera and lens, and the answer to that is a resounding yes.

There are no shortage of Pentax SLR fans. The Pentax Sv was an early favorite of mine and one that I still consider to be a near perfect classic SLR. Is the Pentax K even better? Not on paper. The Pentax K’s viewing screen is ever so slightly darker than the later Sv and all Spotmatics, you need to manually press a lever on the lens to activate the automatic diaphragm, the shutter speed dial rotates while the shutter fires (which if your finger accidentally touches while it’s moving can throw off your shutter speed) and there’s no self timer.

But this is a camera review site, and sometimes things are more than the sum of it’s part (or features) and in that respect, the Pentax K is a gorgeous, heavy camera, hand made by passionate technicians and engineers in the early days of Japanese SLR dominance. The camera was nearly perfect from the moment it first hit the market. It predated SLRs from Nikon, Canon, Minolta, Konica, and Yashica, yet when handling it today, it does not feel like an early SLR. There’s no left handed controls of an Exakta, film advance knobs, blackout viewfinders, or any other “compromises” that early SLRs had.

It is commonly said that these early Pentaxes were all hand made and not done using any automation. I can’t say for sure if that’s true or not, but the camera has a fit and finish that compares favorably to other hand made cameras like Nikon and Leica rangefinders. The camera has heft, excellent balance, and perfect fit and finish. The shutter fires with a satisfying “snick” typical of the best focal plane shutters of the day.

And of course, there’s the looks. The round slow speed knob on the front of the camera is cool as hell, even though it’s technically considered an inferior design. The camera’s soft edges around the prism, top plate, and film advance lever are elegant. I’ve never seen an early Pentax with a peeling body covering suggesting that whatever they used was a step above lesser coverings that are known to crack off or shrink.

Asahi hit a home run with both the design and build quality of these early Pentax bodies. The optics of their lenses were as good as anything out there. They were smart for using the M42 screw mount to piggy back on the success of established German cameras rather than come up with an all new lens mount.

Simply, the Pentax AP and Ks are two of the finest 35mm SLRs ever made. I’ll fight anyone who says otherwise…

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pentax_(original)

https://www.cameraquest.com/pentorig.htm

https://www.pacificridgephotography.com/Photography/Gear/Pre-1960-Asahi-Cameras/

http://www.pentax-slr.com/71760545

Just got a mint-condition SP and 135mm f3.5 Takumar M42 (no auto) lens (each with the original leather cases) free this weekend from the local Freecycle list. Looking forward to running some test film (currently in love with Ektar 100 for sunny, daylight shots) through it and trying my other M42 lenses…. Thanks Mike!

Very cool! I am sure you will enjoy shooting it, and most likely, will be the first of many more Takumars to come! One tip, even though the SP might be in cosmetically great shape, check the light seals in the film compartment before shooting. Even the nicest cameras can often have degraded light seals that need to be replaced before shooting.

As usual, a well done expose of an historic camera. I have a near mint K that was overhauled by (Eric Hendriksen) the Pentax man. Regardless, a shutter blind ribbon let go later on, due to age, and has not been repaired yet.

About automatic lenses: I have a Pentax H2 and it seems to me that it doesn’t work well with an automatic lens. The reason seems to involve the amount of throw the stopdown lever has. A semi-automatic lens only needs enough throw to trip the lens, but the automaic lens needs enough throw to cover the full range of throw that extreme apertures have.

And yes, I share your opinion about the SV.

Regards,

Arnold

Thanks for the comments Arnold. You could be onto something with the longer throw of the fully automatic lenses. I’ll admit to only doing a quick test with a Super Takumar 55/1.8 on the Pentax K. I saw it activate the iris and did no further testing. I wouldn’t be surprised at all if it wasn’t fully compatible with every lens out there though. Thanks for the tip.

A fine review, Mike – first I’ve seen the first two Pentaxes profiled side-by-side. As a half-century user of Pentax gear, I’ve got several H and S nonmetered bodies plus an Asahiflex in the collection, next to more modern gear. Let’s not overlook, however, the legendary and rare Zunow SLR which, when introduced in 1958, offered instant return mirror, semi-auto diaphragm, lever film advance, a single shutter speed dial offering 1 sec thru 1/1000 sec, DOF preview, and interchangeable prism finders … not to mention the incredibly good Zunow lenses. You might argue not to consider the Zunow as a marketplace competitor to Orion or Asahi, and I’d agree, as it appears less than one thousand were ever built, and none were officially exported to the USA. Stephen Gandy has a good article on Zunow’s lenses and the SLR.

The Pentax K may be my perfect screw mount Pentax. It has the usability and quality of the later cameras, but with just enough quirks of an early SLR to never be boring.

Thanks for the info on the Zunow. That is a camera that I’d love to one day be able to write about on this site.