Another Halloween, another Cameras of the Dead article. This year, as I browsed through my ever growing collection of broken cameras, I started to see a pattern. While sure, I have my fair share of broken Japanese, American, and Soviet cameras, but I’m starting to see more and more European cameras.

But these aren’t just any European cameras, made by Leitz, AGFA, Voigtländer, or any of the other large German companies, no, these were from companies that little is written about. So I thought that I could tie in some obscure European cameras with obscure European horror.

And when it comes to European horror, there is no one better than Italian filmmaker, Dario Argento! Am I foreshadowing an Italian made camera in the article below? No, but just go with me on this one!

Argento’s IMDb page credits him 42 times as a writer, 26 as director, 17 as producer, and another 13 as an actor so it’s pretty safe to say, he has had a rather prolific career. Many of his movies are in Italian, including two of his more successful ones, Opera and Suspiria, but my favorite was a movie he co-wrote with none other than George A. Romero, Dawn of the Dead. Released in Europe with a completely different edit as Zombi, and a shorter run time of 116 minutes, Argento strangely omitted several scenes from the US version, replacing them with unused footage from other versions.

Argento’s IMDb page credits him 42 times as a writer, 26 as director, 17 as producer, and another 13 as an actor so it’s pretty safe to say, he has had a rather prolific career. Many of his movies are in Italian, including two of his more successful ones, Opera and Suspiria, but my favorite was a movie he co-wrote with none other than George A. Romero, Dawn of the Dead. Released in Europe with a completely different edit as Zombi, and a shorter run time of 116 minutes, Argento strangely omitted several scenes from the US version, replacing them with unused footage from other versions.

His most controversial change to the movie is including an all new musical score by the Italian progressive rock band, Goblin. Many fans have debated over the years whether Argento’s cut of the film was any better than Romero’s US version, or if Argento’s contributions to the making of the movie had anything to do with making it great, but whatever his role in it was, the original Dawn of the Dead remains my favorite horror movie of all time.

And like the many iterations of Dawn of the Dead, Argento had a way of doing things just a little different. Just like these three cameras here. None of them are revolutionary in any one way, but whether it’s a strange design, or a curious re-engineering of an already proven concept, or simply adding a high end feature to a cheap camera, each of this, the 7th edition of Cameras of the Dead, are Euro-Horror!

So go grab a cup o’ brains, sit back and enjoy three quick looks at the Fex Ultra Fex, OPL Foca PF3, and the Apparate & Kamerabau Akarette II.

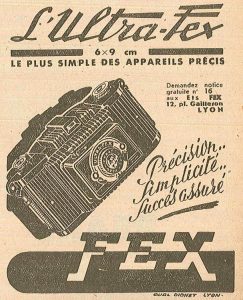

Fex Ultra Fex (1947)

This is Ultra-Fex, an inexpensive Bakelite camera made in France by Fex (acronym for French Export) between the years 1947 to 1966. It shoots eight 6cm x 9cm images on 620 roll film. The camera is very ornate, but also very basic, featuring a fixed focus meniscus lens, a collapsible front, and a curved film plane. The shutter has two speeds, plus Bulb, and there are two diaphragm sizes, labeled “Normal” and “Intense”. There are a couple of different variations of this camera, some with a flash port, but they all have the same basic formula. It’s simplistic feature set and long production run suggest it was an inexpensive option for children or beginning photographers.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (eight 6cm x 9cm images per roll)

Lens: ~90mm ~f/11 Fexar Optic Spec uncoated Meniscus

Focus: Fixed Focus ~2m to Infinity

Viewfinder: Optical Scale Focus

Shutter: Metal Blade

Speeds: P (Bulb), 1/25, and 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 444 grams

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/UltraFexManual.pdf (in French)

My Thoughts

I like all kinds of cameras. If you’ve been reading this site for any length of time, you’ll see that I give equal attention to high profile cameras like the Kodak Ektra as I do cheap box cameras. If it’s a camera and looks interesting to me, then there’s a chance I’ll review it.

This Fex Ultra Fex (what a name) was formerly part of the private collection of master-collector, Ira Cohen, and when it came to me, I couldn’t tell what kind of camera this was. Was this a high end medium format camera, or a cheap piece of Bakelite. Well, without going any farther, seeing the camera’s large size, but light weight of 444 grams should tell you all you need to know.

There’s no way that anyone could say with a straight face that there’s anything “Ultra” about this camera, except maybe the ultra-blue ring around the lens. Why is that even there? Maybe it’s to trick you into thinking the uncoated single element lens has that fancy blue multi-coating that was just starting to become popular around the time this camera was first produced.

The camera shoots 6cm x 9cm exposures on Kodak’s 620 film which I find pretty strange, considering that only Kodak and a few small American companies ever supported 620, so why this French built camera supported it, is anyone’s guess.

The Fex Ultra Fex was in production for nearly two decades and it’s cheap design suggests it sold for very little and probably was a popular choice for amateurs or children. As with most cheap cameras, the shutter is a rudimentary spring design with only 2 speeds. The great thing about cheap cameras like these, is that their mechanics are so basic, there’s nothing to go wrong. Well, not here.

Unlike other children’s cameras or simple box cameras, the shutter on this Fex Ultra Fex didn’t work. Upon close inspection, pressing the shutter release moves a spring tensioned “flap” over a hole through the back of the lens, but it’s supposed to catch a second flap, which opens the shutter exposing film, but this catch is broken. How did this happen? Was this particular camera used so much that it wore out, or is the camera so cheaply built that the French camera makers who built it, couldn’t even get a two speed shutter to work?

Had I been able to shoot the Fex, I would have loaded film by first removing the back of the camera which is held on by sliding metal clips on both sides. The camera’s cheap construction really shows in the film compartment as you can visibly see a spring connecting one of the metal flaps of the shutter through a rectangular opening in the film gate.

The film plane is curved, which is a common trick for single element meniscus lenses to maximize sharpness at the corners, but there is no film pressure plate. The curved rear door of the camera has several horizontal strips that put pressure on the film as it transports through the camera. A warning on the inside of the rear door says “Utilise les bobines 6×9 a joues reduites” which Google Translate suggests is “Uses 6×9 coils with reduced cheeks”, so those of you with large cheeks might want to stay away.

The top and bottom of the camera are quite barren featuring only the advance knob and another knob which does nothing. On the bottom is a 3/8″ European tripod socket. Had you wanted to mount the camera to a modern tripod to shoot images in Bulb (indicated by a P) mode, you’d need a 3/8″ to 1/4″ adapter.

The Fex has a collapsible front which must be extended to properly shoot the camera. With the camera collapsed, it is still quite big and would not easily fit in a small bag, owing to the very large body. The shutter release is positioned on the top of the shutter plate and would normally have had some type of rotating flash collar, which on this example has broken off.

The front of the camera has switches for changing between shutter speeds of 1/25, 1/100, and P (Bulb), and on the other side, an aperture selector labeled “Normal” and “Intense”. Like other cheap cameras, there is no iris in the camera, rather a metal plate with a smaller hole that when set to “Intense” decreases the opening of light from the lens to the focal plane.

The Ultra Fex is a neat looking camera that I was bummed I couldn’t shoot. While doing some research for this article, I found some sample images on the Lomography site showing that the camera delivers surprisingly good shots, including some shot on 35mm, suggesting the single-element Fexar lens was of decent construction.

I also saw that there was a name variant of the Ultra Fex called the Lumiere Lutac that also appeared to have been sold in France around 1957. The Lutac is cosmetically different, but the overall shape and feature set of the camera clearly show that it’s the same camera.

Regardless of what could have been, this particular Ultra Fex has likely been deceased for far longer than I’ve had it, and it’s unlikely it will ever shoot any more photographs again.

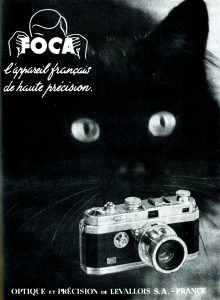

OPL Foca PF3 (1953)

This is a Foca PF3, sometimes called the “three star” for the three stars that appear on the front plate of the camera, made by Optique & Précision de Levallois, in Levallois-Perret, France between 1947 and 1957. The Foca PF3 was a 35mm rangefinder camera that is sometimes called the “French Leica” for it’s similar feature set. It was often seen as a more cost effective alternative to the Leica in France as it was not subject to steep tariffs and import taxes. The cameras were generally high quality, but are rarely seen outside of Europe today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.9 Foca Oplarex Coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Foca PF Screw (~36mm) Mount

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Coincident Image Rangefinder.

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Accessory Shoe with PC Port M and X sync

Weight: 925 grams (w/ lens), 735 grams (body only)

Manual: None

My Thoughts

When you make a camera as successful as the Leica rangefinder, everyone wants to copy you, and copy the Leica companies did. Nearly every company from every country, made Leica copies. Companies from the Soviet Union, Japan, England, the United States, Italy, and even France all made cameras that were either exact copies, or similar enough to be considered “Leica Copies”.

When you make a camera as successful as the Leica rangefinder, everyone wants to copy you, and copy the Leica companies did. Nearly every company from every country, made Leica copies. Companies from the Soviet Union, Japan, England, the United States, Italy, and even France all made cameras that were either exact copies, or similar enough to be considered “Leica Copies”.

While some of these copies were like the Soviet Zorkis and FEDs that externally were nearly identical, there were others that took a few liberties making cameras that were more “Leica-inspired” than downright copies. The Foca rangefinder from Optique & Précision de Levallois, or OPL for short, was such a camera.

OPL was founded in 1919 but had roots as far back as 1911 as an optical company making all sorts of military rangefinders, scopes, and other lenses. By the late 1930s, OPL started work on their own compact 35mm camera that they had hoped would compete with quality German cameras like the Leica. The European economy in the late 1930s caused the import of luxury items from Germany to be quite expensive in France and for the few who could afford a genuine Leica, getting their hands on them was another story. By building their own domestic camera, OPL could offer a quality camera for much less.

Development of this new camera was halted during the war, but in 1945, OPL was ready to release their new camera which they simply called the PF for ‘petit format’. Rather than give the camera a name, each model would be indicated by a number of stars. The base model, or Standard, would be the PF 1 Star, or simply PF Standard. The PF 2 Star would add a coupled rangefinder, and the PF 3 Star from 1947 would add an additional slow speed dial on the front of the camera.

All Foca cameras would shoot the same size 24mm x 36mm images on Kodak’s 135 format 35mm film, would have a focal plane shutter, and have an interchangeable screw mount lens. Later Foca cameras would switch to a Foca specific bayonet mount, but otherwise were the same.

Foca cameras were made in small quantities for the French market and were not actively exported to other countries, so finding any of these models in the US today is very difficult. Most of the websites I found while researching this article were in French and I had to use Google Translate to try and piece the facts together. I have no idea how much these cameras cost when new and I found very little marketing or advertising material to see how they were sold.

This particular camera has serial number 408,193 which I believe is a later model, and was loaned to me by fellow collector Kurt Ingham but sadly, was inoperable. Although the camera was in cosmetically very nice condition, I could not get the shutter to fire at any speed. This shouldn’t be surprising as it was a uniquely designed shutter, built in small quantities by a company that did not have a lot of experience making focal plane shutters.

On the upside though, the Foca PF3 is a gorgeous looking camera. Although many people call these “French Leicas”, I think that moniker doesn’t do it justice. Aside from shooting the same size images on the same film format, the two cameras have nearly nothing alike.

The PF3 is a heavy, solid feeling camera, weighing in at 735 grams body only and 925 grams with the Foca Oplarex 50mm f/1.9 lens, this camera is quite a bit heavier and wider than a Leica II or III.

The body is wide, which allows for extra room on the top plate of the camera, giving it an uncluttered feel. On the left, the rewind knob also doubles as a film reminder dial. Since this camera is meterless, a reminder is all you’ll get. Next to it is an accessory shoe which likely would have been used with variable viewfinders or flashes. The shutter is flash synchronized for both flashbulbs and electronic flashes, via two PC sync ports on the camera’s left side.

The shutter speed dial is a lift and set type with fast speeds from 25 to 500 plus Bulb on top and 1 to 25 on the separate slow speed dial on the front. Since I was unable to use this camera, nor could I find any sort of user’s manual, I can only assume that you must set the top dial to 25 before the slow speed dial will work. Another assumption that I can’t prove, but is probably a good idea, would be the make sure the shutter is cocked before changing any speeds. It might not be a requirement, but it certainly wouldn’t hurt anything.

Lastly, we have the threaded shutter release and non automatic resetting exposure counter.

On the bottom of the camera is a combined European 3/8″ tripod socket and film back release that is used to remove the entire back of the camera. Fold out the handle and twist it 180 degrees and the back and bottom come off. The Oplarex lens on this camera is collapsible so I show a side profile shot of it extended.

Loading film into the Foca is easy with the back removed. There is a folding plate that covers the film as it goes over the film sprockets to maintain pressure on it. Film transport is from left to right onto a removable take up spool, which suggests cassette to cassette film transport was possible. On the inside of the film door is a warning in French that I think says not to leave the shutter cocked when the camera is not being used. Perhaps this warning was not needed as is the reason that the shutter was inoperable on this example.

The camera has an interesting body mounted helical with a depth of field scale that moves with the lens as it focuses, and with the completely removable film back.

The Foca is a really good looking and unique camera that is more deserving than the name “French Leica”. It should just be called a Foca as it stands on it’s own. For the era in which it was made, the viewfinder is large and bright with an easy to use coincident image rangefinder patch. Although I could not shoot any images with this camera, the 6-element f/1.9 Oplarex appears to be well constructed and likely would have made very good images.

Sadly, dead cameras happen and no matter how promising it may have been, their inclusion in these articles is the best I can do…unless I find another!

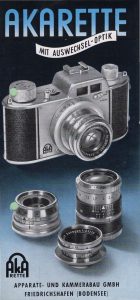

Apparate & Kamerabau Akarette II (1950)

This is the Akarette II, a 35mm interchangeable lens camera made by Apparate & Kamerabau Gmbh in Friedrichshafen, Germany starting in 1950. The Akarette series consisted of a variety of simple cameras that usually came with one of several high quality Schneider lenses. A distinct feature of this camera is the two viewfinder windows are for two different focal lengths of 50mm and 75mm. The camera sold modestly as a lower cost alternative to other higher end German cameras. Apparate & Kamerabau would later make an interchangeable lens rangefinder camera called the Arakrex.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 Schneider-Kreuznach Xenar coated 4-elements

Lens Mount: Aka Breech Lock Screw Mount (~38mm)

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Twin Scale Focus Viewfinders, one 50mm and the other 75mm

Shutter: Prontor-SVS Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash: Accessory Shoe with PC M, X, and FP Sync

Weight: 533 grams (w/ lens), 452 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/akarette_ii.pdf

My Thoughts

Sometimes there are those cameras that from the moment you see one, you know you need to find one and there are others that just appear. This Akarette is the latter. Showing up in a miscellaneous “box o’ junk”, the camera, was in fact, junk. Dirty, smelly, and completely inoperable. It sat in the bottom of that box for months before I even gave half a thought of cleaning it up and possibly reviewing it.

After eradicating most of the funk, I was unable to get the shutter to fire, but at least saw what seemed to be a pretty interesting camera. The Akarette was one of those aspirational cameras that sold cheaply, but had some features of more expensive cameras, hoping to serve as a stepping stone between a basic box camera and a professional one.

Featuring a proprietary breech lock screw mount that is incompatible with any other camera system, a capable shutter, twin viewfinders, and a selection of good Schneider lenses, the Akarette was a compelling option for the photographer who wanted to make good photos, but couldn’t afford a Leica or a Contax.

The Akarette was first released in 1947 and between then and 1950, a total of three versions were released all of which had similar features. The differences between the three were a combination of cosmetics, shutter upgrades, and minor features such as a film reminder dial. In 1954, the Akarette II was renamed the Akarelle and switched from a film advance knob to a lever and the telephoto viewfinder from 75mm to 90mm, but otherwise was the same camera.

In the catalog above, an Akarette II with the Schneider 50mm f/3.5 lens on the camera reviewed here, sold for 185 DM. According to the historical currency charts at fxtop.com, in 1953, 1 DM was equal to $0.24 USD so back then, it would have sold for the equivalent of $43.92. When adjusted for inflation, that compares to $417 today, making the Akarette a semi-affordable, but not cheap, camera.

The Akarette is a solid feeling camera that’s just the right size for those with small to average sized hands. Weighing 533 grams with the Schneider Xenar lens pictured here, the Akarette is weighs near the same as a Leica II with collapsible Elmar. The rounded edges on the top plate and sides make the camera very easy to hold. The top plate has from left to right, the rewind knob, accessory shoe, manually resetting exposure counter, threaded shutter release button, and combined film advance knob and film reminder, oh, and there’s strap lugs.

The bottom of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket and on the base of the shutter is a red tipped self-timer lever.

On the back, we see the openings for both viewfinders, and an elaborate film exposure guide written entirely in German. I do not know if English versions of this guide exist, but based on how cluttered it looks, it seems overly complicated and not something I’d likely ever use.

The film compartment opens by sliding the lock on the cameras left side. Film travels from left to right onto a fixed take up spool in a rather ordinary looking film compartment. Notice that within the film compartment, beneath the viewfinder openings is the serial number.

The lens mount on the Akarette is not a traditional screw mount like the Leica. Instead, it uses a breech lock system, similar to the Leidolf Lordomat, in which the lens is mated to the camera, aligning a pin on the body with a notch on the lens, and then a threaded ring around the lens is rotated to secure the lens. The example here has a Schneider Xenar 50/3.5 lens and based on the small amount of documentation I’ve found on these cameras, it seems as though Schneider was an exclusive maker of Akarette lenses. I do not know if any other third party companies made compatible lenses, but a quick Google image search doesn’t seem to turn up any.

Near the 1 o’clock position around the lens is a switch for toggling between the 50mm and 75mm viewfinders. Only one viewfinder is active at a time as this lever moves a black plate with a red dot in front of whichever one you don’t have selected.

I quite like holding the Akaratte and from the top down, it ever so slightly reminds me of a Streamliner motor home with it’s polished metal and soft curves.

Not having the ability to shoot this camera, I am unable to share with you any sample pics, but I found a couple of shots taken with a very similar Akarette II at my friend Mark Faulkner’s GAS Haus website, so give his site a visit and check them out. If I ever do come across a working example, I’ll be sure to write about it!

My Conclusions

This being my 7th Cameras of the Dead article of which there are always 3 reviews in each, I’ve now written about 21 dead cameras, and frankly, I have a lot more.

I won’t always take the time to write something about every dead camera, as I reserve these articles only for those interesting enough to put something out there. Lately, there seems to be a 50/50 chance after writing about a dead camera, that one in working condition shows up in my collection, so I’ll admit to picking cameras that I kinda maybe one day hope I’ll get a second chance to review.

Until that happens though, I hope you’ve enjoyed yet another look into three cameras that for one reason or another, have taken their last photographs and henceforth will exist on the Internet as a Camera of the Dead.

Hello Mike, that was a nice article !

FEX really was an institution in France. Every (now aging) kid had its FEX camera, and it is probably the most easy camera to find there, even easier than the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye.

There are a large number of Fex cameras: Fex Ultra, Sport Fex, Fex Delta, Fex Elite,… who are just versions of the same camera, when there are any differences at all.

There is a ‘TLR’ version of the FEX taht looks reaaaally nice and is also easy to find in France: the Fex Ultra Reflex. Look it up and you’ll find some resemblance with your own. 🙂

Also, other renamed versions exist: the Bauchet Mosquito I and II were made by Fex for the film company Bauchet, just as they didi for Lumière.

About FOCA, when the PF3 was issued, they already had an history of making their own focal plane shutters. The most encountered cause of death for their cameras is shutter curtain material decay. There is nothing wrong with changing speeds with the shutter cocked BTW. But mechanical issues also happen, as well as old greases that may lock the shutter mechanism. Alas they are really complex cameras to repair, and you need specific tools to access the inside.

You can find original prices and availability in distributors catalogs that can be browsed on the english version of Collection Appareils http://www.collection-appareils.fr/gestion_catalogue/html/recherche_eng.php?nom=&type_appareil=&marque=Foca&modele=PF3&format_fr=&marque_obj=&modele_obj=&ouverture=&marque_obtu=&modele_obtu=&submit=Find+it+%21

Wow! Great info! I figured that the Fex was a popular camera for children as it was in production for a very long time! Maybe one of these days, I’ll come across another, or one of the Fex variants.

That’s also good to know about the Foca shutter! It’s definitely a nice camera, and a shame that I couldn’t shoot it.