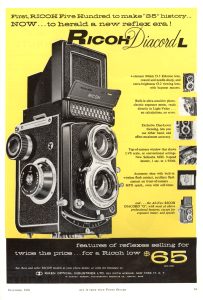

This is a Ricoh Diacord L, a twin lens reflex medium format camera, made by Riken Optical Industries LTD starting in 1957. The Diacord was the name of the export model and the L suffix indicated that it had an uncoupled selenium light meter for exposure measurement. The Diacord L was one of the last in a robust lineup of TLR cameras produced by Riken, starting with the Riken Ricohflex from 1951. The Diacord compared favorably with other premium Japanese TLRs such as the Minolta Autocord and Yashica lineups of TLRs from the same era.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm images per roll)

Lens (taking): 8cm f/3.5 Rikenon coated 4-elements

Lens (viewing): 8cm f/3.2 Ricoh Viewer coated 3-elements

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Reflex Waist Level Finder w/ Sports Finder

Shutter: Seikosha-MXL Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium exposure meter w/ EV Scale

Battery: None

Flash Mount: PC Port with M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1104 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/ricoh_pdf/ricoh_diacord_l-1.pdf

Manual (alt version): http://www.cameramanuals.org/ricoh_pdf/ricoh_diacord_l-2.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Ricoh Diacord L was one of the last TLRs made by Riken Optical and is one of their most well featured. It offers a competitive feature set to nearly every TLR ever made, and was a tremendous bargain both when it was new and today. It has an uncoupled selenium exposure meter that is easy to use, a very bright viewfinder, and an excellent lens. I’ve used a number of other TLRs over the years, many of which cost quite a bit more, but for what was considered an economy model when it was new, there are nearly no compromises with this camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for extreme value, both in 1957 and in 2019 | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

Ricoh, Ltd. is the name of a multinational company making products in a variety of industries in over 180 countries, whose headquarters are in Tokyo, Japan. One of Ricoh’s child companies is Ricoh Imaging Company Ltd. who is the current maker of Pentax brand DSLR and Ricoh point and shoot cameras.

The current Ricoh company was founded in 1936, but there was a separate company named Rikagaku Kenkyūjo (in English: Physico-Chemical Research Institute) that started in 1917 as a chemical apparatus institute who researched and developed a variety of products, including chemicals used during the manufacture of photographic film. In their earlier years, Rikagaku Kenkyūjo was only a research institute that didn’t actually sell anything in the open market, but in 1926 they changed their name to Rikagaku Kōgyō K.K. and began to market the products developed by the institute.

Rikagaku Kōgyō K.K. products were used in all areas of Japanese manufacturing, but in February 1936, the photographic paper division branched off into it’s own separate company and was known as Riken Kankōshi K.K. The name “Riken” was chosen as an abbreviation to the company’s original name RI-kagaku KEN-kyūjo.

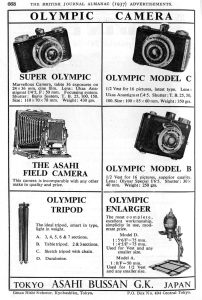

A year after it’s foundation, Riken would purchase another Japanese company called Asahi Bussan G.K. who had previously manufactured a 35mm leaf shutter camera known as the Olympic. The Olympic, and a higher spec model known as the Super Olympic would be Riken’s first cameras manufactured under their name. Together with their photographic chemicals division, along with their new ability to make cameras, Riken quickly became one of Japan’s premiere photo companies.

In 1938, the company would change it’s name once again to Riken Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K., or in English, Riken Optical Industries Co., Ltd, a name which the company would be known by until 1963. This same year, Riken would introduce it’s first camera completely designed in house, known as the Riken No. 1 which was a solid bodied camera that took 3×4 images on 127 roll film.

The Riken No. 1 was sold under a variety of names, one of which was the Ricohl, the first appearance of the name “Ricoh” in one of Riken’s products. The Riken No. 1 has a very complicated history that has it’s very own Wikipedia page which I encourage you to read if you want to know more.

Around the start of the war, Riken would produce a variety of cameras including a 6×6 TLR known as the Ricohflex. The Ricohflex would be one of Riken’s earliest successes, launching a whole line of Ricohflex TLRs that were in production from 1939 until at least 1954.

Prewar and early post war Ricohflexes were pretty basic cameras with simple shutters and lenses, and externally coupled focusing lenses, much like the Argus Argoflex and Kodak’s later Kodak Reflex TLRs.

In 1955, Riken released an upgraded TLR model called the Ricohflex Dia which moved away from the geared lenses of it’s predecessor, instead featuring a moving front lens standard, very similar to the Minolta Autocord, which itself was similar to the Franke & Heidecke Rolleicord. The original Dia featured Seiko or Citizen shutters, an automatic film advance, and a paddle focusing rack on both sides of the camera, but lacked the Bay 1 filter mounts, instead relying on simpler push on filters.

As was the case with many Japanese makers, the camera was continually revised with incremental updates including better lenses, better shutters with faster speeds, and eventually light meters.

In late 1957, an updated model made it’s debut which was officially was marketed as the Ricoh Dia in Japan and Diacord in western countries. Strangely, promotional pictures and images from the camera’s user manual still show it with a Ricohflex name plate, but none sold to the public have been found with this name.

The Dia/Diacord was available in two variants, the ‘G’ and the ‘L’, which were nearly identical with the biggest difference being the Diacord L had an uncoupled selenium exposure meter behind the name plate. Otherwise the Dia/Diacords G and L had either a Citizen or Seiko shutter, flash hot shoe with both M and X flash synchronization, a bright reflex viewfinder, support for Bay 1 filters, and a self-timer.

When it was released, the Diacord L and G both sold for $65 and $46.50 respectively, which when adjusted for inflation, is comparable to $575 and $415 today. These prices were a bargain compared to the Minolta Autocord which sold for between $99.50 and $124.50, or the German Rolleiflex which was over $200.

The Dia and Diacord represented two of the best TLRs made by Riken. Only the later Diacord 225 with film advance crank and Ricoh Auto 66 with a semi-automatic match needle coupled exposing system topped the features of the Dia/Diacord.

Despite offering what looked to be feature packed models at very competitive prices, it would seem that Riken’s TLRs failed to capture the same market as other Japanese TLR makers like Minolta and Yashica. In 1963, Riken would officially change it’s name to Ricoh, adopting the name of it’s most successful product. Ricoh would continue to make 35mm SLR cameras using the M42 screw mount and eventually the Pentax K-mount well into the 1980s. The company would never regain it’s reputation as a leader in the Japanese camera industry, but obviously did enough to stick around as the company still exists today.

Today, little is discussed or written about Ricoh’s TLRs and frankly, I cannot understand why. Perhaps it’s because of the close similarity to so many other Japanese TLRs, or that people just group this into a vague category of “Rolleiflex copies” and while yes, there are elements of it that take a lot from the Rolleiflex, there’s enough different about it, that when combined with it’s extremely low price, makes it worth a serious look today.

My Thoughts

My first exposure to the Diacord was seeing one posted in the Vintage Camera Collector’s Facebook group by fellow collector, Mike Novak. Mike’s Diacord was in excellent condition and reminded me very much of the Minolta Autocord that I had previously reviewed and I was already a fan of Ricoh cameras like the Ricoh 519M and Anscomark M. Once Mike started showing some sample pics of his, I knew I had to have one.

After acquiring a Diacord L of my own and getting everything together to start on this review, I thought I would see if Mike had any interest in perhaps typing a paragraph or two of his thoughts on this camera and he gladly accepted.

A couple of days later, he emailed me his contribution, and instead of merely just a paragraph or two, he pretty much typed my whole review for me! So for today’s review of the Ricoh Diacord L, rather than hear me ramble on about it, here is Mike’s excellent “article within an article”.

“I want to buy a TLR camera. Which one should I get?”

This is a question that is quite commonly asked in many of the film photography groups and forums that I belong to on Facebook and many other social media platforms. It will come as no surprise to anyone that knows me on these platforms that my favorite TLR, or any square-format medium format camera, is some variation of the Rolleiflex Automat.

But my answer to the question that the poster should be asking, which is “can you recommend a good TLR camera for someone that has never used a TLR camera before?”, might be surprising. A good Rolleiflex is a lifetime investment, and should not be a camera that an inexperienced user should purchase lightly. There are many better, lower cost alternatives that should be considered.

The most commonly mentioned “low-cost” alternative to a Rolleiflex Automat is the Yashica Mat 124 G. While there is no doubt that the four-element Yashinon lens is a very good performer, those who claim that the Yashica is “just as good as a Rolleiflex, only cheaper” have either not checked the average “sold” prices of the Yashica on eBay, where it often sells for as much as more than all but the late model Automats, or have never actually handled a Rolleiflex. Much better offerings from Yashica for a starter TLR are the Yashica-Mat LM, EM, or the three-element Yashica D (the very last Yashica Ds had a four-element Yashinon lens) or Yashica 635, the latter two having the same three-element Tomioka-made Yashikor lens that is labeled as the Tri Lauser on many other less-expensive Japanese TLR cameras made by Tougado and other Japanese makers. In any case, the four-element late model Tessar and Xenar-equipped Rolleicord cameras offer much better value than any of the Yashicas.

So, Rolleiflex Automat, Rolleicord, or Yashica? What else is there? The Zeiss Ikon Ikoflex cameras I consider on equal terms as Rolleiflex Automat. Excellent cameras, but for a “first” TLR? Maybe not. They can be quirky and non-intuitive for a beginner. A Minolta Autocord in good condition is every bit the equal in build quality and performance as a four-element Rolleiflex, and the Rokkor lenses are superb, but finding one in good working condition may be problematical, as they are prone to problems with the focus mechanism, and repairs can be expensive.

The East German and other FSU cameras are a bit more esoteric, and not common on the North American market, and I am sure that there are others who can give a more qualified opinion on them than I can. So what is left? Are there any high-quality bargain TLR cameras that won’t break the bank for a medium-format neophyte? (Edit from Mike E: Hey, you forgot about the Czech-made Flexaret!)

The mid to late 1950’s were the heyday of the Japanese consumer TLR industry. While the major Japanese players were concerned with the professional or serious amateur rangefinder market, or perfecting what we now think of as the modern single-lens reflex camera, many others were producing variations on the tried and true twin lens reflex camera. There were a bewildering number of consumer TLR cameras, most following the simple formula of the pre-war Rolleicord cameras, with knob advance, triplet lens, and a non-automatic frame advance utilizing a ruby window, really an evolution of the simple box camera that first brought photography to the mass market. With very few notable exceptions from makers such as Minolta, Yashica, Aires, and Beauty, as well some short-lived and quite rare examples from Konica, Fujica, and others, these “picnic TLRs” that dominated the market were pretty much interchangeable, only the nameplates are different.

Ricoh fell largely into this second category. They produced their first TLR camera in 1943, the Ricohflex Mod. B, which was a direct copy of the much earlier German-made Richter Reflekta. The Mod B was described in the contemporaneous Japanese press as “already antiquated at the time of its release.” This was a very simple TLR camera that used not one, not two, but three ruby windows to advance the frame. While a fun camera to use and not without it’s charms, the Mod. B cannot be considered as anything more than a curiosity.

After the war, Ricoh continued on the simple path, with a series of popular Ricohflex cameras that utilized the same geared-wheel focus as the Kodak Reflex TLR cameras, with front-focusing three-element anastigmat lenses and no automatic frame advance. But with the introduction of the Ricoh Diacord L in 1957, and its siblings the Ricoh Diacord G and finally the Ricohmatic 225, Ricoh took a strong turn towards the serious amateur TLR market dominated by Minolta and Yashica. While none of these cameras where groundbreakers, they did exhibit the best that was available in Japanese cameras of the time, with four-element lenses, automatic frame counters, unit focusing, and in the case of the 225, crank advance.

The Diacord L is a well-built and feature rich TLR camera with an exceptional four-element Rikenon taking lens, a Seikosha MXL shutter with speeds ranging from 1 – 1/500 second, an on-camera, uncoupled selenium light meter, a bright viewfinder, and it uses the near-universal Rolleiflex bay 1 accessory mount, allowing all of the excellent Rollei filters, lens shades, and other accessories. It marries many of the best features of the German TLR cameras with the simplicity of the Japanese consumer cameras.

The “L” in the model name refers to the selenium exposure meter that is conveniently located behind the camera’s name plate. If you look closely at the name plate, you’ll see two long slits that allow some light to pass through the meter for use in brightly lit outdoor scenes. When using the camera indoors, or in low light situations, the name plate flips up the reveal the entire surface of the light meter.

To meter correctly with the plate in either the up or down position, you must set the meter readout to either the Opened or Closed position depending on how the name plate is set. With the camera pointed at a scene you intend to photograph, a red needle on the photographers right side can easily be seen with the camera at waist level, and will point to an exposure number from 4 to 17. Then, by adjusting either of the shutter speed or aperture f/stops so that a matching exposure number is selected in the window above the viewing lens on the front of the camera, proper exposure can be made. I was fortunate that the light meter on my camera was not only working, but also accurate, but if you find an example with a dead meter, or just don’t wish to use it, you may select any combination of speeds or f/stops that you wish.

What sets this TLR camera apart from the others, including the Rolleiflex, is it’s unique twin-lever seesaw focus mechanism that works with either your left or right hand, which makes it, in my opinion, as the owner of more than sixty twin lens reflex cameras, the easiest camera of its type to focus quickly.

In use, this camera is similar to most of it’s type. While not as sturdily built as the Rolleiflex or the Minolta Autocord, it is considerably lighter in weight, with well designed and intuitive controls. Mine was rugged enough to survive a three-foot drop onto asphalt with only minimal cosmetic damage to the viewfinder cover. I would not recommend trying this at home. Again, all pretty standard stuff.

The viewfinder is bright enough to use even in well-shaded area, and the previously-mentioned see-saw mechanism makes focusing quick and easy. But the heart of the camera is the four-element coated Rikenon taking lens, which is every bit the equal of the much more well-regarded Zeiss Tessar, Schneider Xenar, Minolta Rokkor, or Yashica Yashinon used on the other more often mentioned TLR cameras. This lens produces images that are sharp to the edges even wide open, and it renders colors that are vibrant and contrasty (is contrasty a real word?).

So, to answer the original question, “I want to buy a TLR camera. Which one should I get?” All things taken into consideration, including cost, build quality, reliability, and most importantly, performance, you would be hard pressed to find a better choice than the undervalued Ricoh Diacord L.

My Thoughts…Continued

I don’t really have much else to add to what Mike Novak already said, as my fondness for this camera is at least on par with his. I gave high remarks to the Minolta Autocord in that review, and other than the absence of the rapid wind lever, the Diacord equals, and in some cases exceeds that camera.

Like Mike’s, the exposure meter on my Diacord was also working and accurate, and although I typically despise most EV/LV systems on mid century cameras, I quite liked the one on this camera. The twin ‘paddle’ focus levers was incredibly easy to get used to. I can’t say that I’ve used every TLR ever made, but comparing it to the bottom lever on the Autocord, and the knobs on the Rollei and most clones, I found Ricoh’s implementation to be the best I’ve ever used.

The viewfinder was as bright as they come, with edge to edge brightness almost equal to aftermarket bright screens on other TLRs. Strangely, the magnifying glass on my example was missing from the camera, but even without it, I had no issues focusing, even in low light. For fast action, the front of the viewing hood can be folded down for a straight through sports finder.

Having shot most of the Rollei, Yashica, and Aires TLRs that Mike mentioned above, I absolutely agree with his assessment that the Ricoh Diacord is an excellent choice for someone who is looking for a quality TLR experience with a great lens, easy to use viewfinder, and excellent optics, all for an economic price.

Here is a gallery of several other images I took for this review that show off the camera at various angles.

My Results

I first shot the Diacord in early spring 2019 with a roll of fresh Kodak Portra 160. Porta is my favorite color film to shoot in any format as I find the semi-muted colors more natural than other films and I love the realistic blue skies that it delivers in outdoor scenes. It also has a very high amount of latitude for a color film meaning that if I don’t get the exposure correct, it can almost always be saved in developing and scanning.

I would load up the camera a second time in the summer of 2019 using a very old roll of Kodak Panatomic-X, but sadly, that was a miserable failure because I failed to detect that the tape which secures the film to the backing paper had rotted away and the film tore in the camera. I’ll know for next time.

Thankfully, I had better luck with a third roll, this time with the recently released CatLABS 80 film which is a very affordable all new black and white emulsion that is said to offer fine grain and lots of latitude. I’m a sucker for fine grained black and white film, so I figured I would give it a go.

For a gallery of some of Mike Novak’s sample pics shot through his Diacord, check out his Flickr page:

When it comes to images produced by any 6×6 TLR, it has been my experience that the difference between a good image and a great image is negligible. I’ve been very pleased with images shot on simple Pseudo-TLRs with basic f/7.7 lenses like the Voigtländer Brillant, or American made TLRs with Wollensak triplets like the ANSCO Automatic Reflex, or Japanese TLRs with 4-element Tessar style lenses like the Yashica D.

A combination of a large square negative on medium format film with lenses that tend to offer excellent sharpness in the center and near the edges is something you can expect from any “twin lens” camera. Where these cameras differ is in the subtle ways in which they operate. From a distance, the Ricoh Diacord doesn’t look that much difference than a Minolta Autocord or a Rolleiflex, but once you get used to them, the ergonomics of the controls, the way in whcih you focus the lens, the brightness of the viewfinder are all the ways that separate a great TLR from just an average one, and it’s in that regard that the Ricoh Diacord L excels.

Although this article is 62 years too late, but if I were a camera salesman in 1957 with a potential customer looking at a TLR, my only real justification for promoting a German TLR to that of the $65 Diacord would be to boost my commission check. Is the perfect Diacord perfect? No, but it’s DAMN good, and for the price both in 1957 and in 2019, it is one of the best medium format values out there.

I’m not known for writing short articles, but TL;DR version of Mike Novak’s question, “I want to buy a TLR camera. Which one should I get?” I can wholeheartedly say, the Ricoh Diacord L is the one you should get. Right now. Seriously, log into eBay or whatever camera auction site you prefer and buy one. I’m not kidding, do it….NOW!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://antiquecameras.net/ricohflex.html

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2017/11/28/ccr-review-75-ricoh-diacord-l/

I’m impressed with the photos and the well researched review. Also surprised to see it was of the exact model I was given a few years back (although not as pristine as your example).

I have never taken a picture with although it appears fully serviceable on inspection. Good to know you high opinions of it.

A quick word to the TLR shopper: Gejza Dunay is a 75 +/- year old Czech who runs a camera restoration business in Slovakia. He employs a few vintage gentlemen, all of whom are retired from eastern bloc camera makers. He sells on eBay as “cupog”. I’ve known him for 20 years via the Exakta Circle. Dr. Dunay warns against purchase of the later-model Flexaret TLRs, specifically the models VI, VII and Automat. He tells me that the shutter / advance / cocking linkage is overly-complex and prone to failure … and that these models are best purchased if you live in Slovakia, near Dunay’s repair shop! The earlier Flexaret models are said to be reliable.

Good info Roger. Although I am fortunate that my Flexaret VII is in good working order, you can just feel that it’s a very tight camera that likely won’t last forever. Sometimes more is less, especially when it comes to complex TLRs!

Nice article and interesting info. I bought a Ricoh Diacord L about 4 years ago in very nice condition and put a couple of rolls of film through it. Focusing more on 35mm for a while, I’ve only used it every few months, but recently decided to put some more effort into mastering the square format. Not having experience with many other TLR’s, I don’t have much to compare to, but from what I’ve seen and can feel, the Ricoh seems to be a great camera and is as much as I need.

It really is great. I’d consider it to be 90% of a Rolleiflex at 50% the price. You could spend more money for a German TLR, but you won’t notice a huge improvement!

Thanks – Good to know that it’s a quality camera. I’ve just been looking around on EBay and yes – the Rollei’s are significantly more. I’m planning on shooting some more this weekend. Looking forward to it. Cheers

Hi Mike as ever a really detailed and interesting review. I have just picked one up for 31$, its in very good condition, just missing a small circle of leather bottom left hand side. it will keep my other two TLR’s company Minolta Autocord and Yashica 635.