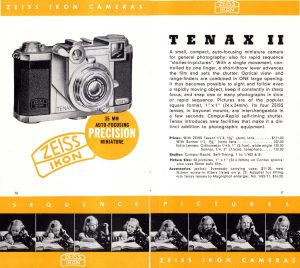

This is a Tenax II, an interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder camera made by Zeiss-Ikon in Dresden starting in 1938. It shot 24mm x 24mm square images on regular 35mm film and was created by famed designer Hubert Nerwin who previously designed the Contax rangefinder. It was an unusually designed camera with a unique lens mounted shutter release that was somewhat copied years later by Konica with their Konica III. The Tenax shares the same name, but not much else to the much simpler Tenax I that first debuted a year after the Tenax II.

Film Type: 135 (35mm) (24mm x 24mm square images, 50 exp on 36 exp roll)

Film Type: 135 (35mm) (24mm x 24mm square images, 50 exp on 36 exp roll)

Lens: 4cm f/2 Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar uncoated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Tenax II Bayonet

Focus: 1m to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Compur Rapid Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/400 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe, No Flash Sync

Weight: 603 grams (w/ lens), 469g (body only)

Manual: none

How these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Tenax II is a fascinating camera designed with a priority on speed and ease of use. Featuring a front mounted film advance lever that not only advanced the film to the next frame, but also changed the exposure counter and set the shutter, the camera was capable of a sequence of shots at a speed that few cameras of the day could match. One of the greatest strengths of the Tenax II is how usable it still is today. It’s use is much more like that of rangefinders from the late 1940s or early 50s and has a modern feel to it. It’s 24mm square images mean you can get as many as 50 exposures on a single roll of film. This is a fun and fascinating camera for any collector or user today. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

The story of the Tenax II starts in the early days of the 20th century. The Carl Zeiss Foundation was a highly respected optics firm that produced lenses, microscopes, binoculars and other photographic related items for a variety of companies all over the world. Lens formulas like the Tessar were licensed out to American companies like Bausch & Lomb which allowed their name to grow even in places where Zeiss factories did not exist.

In the years prior to the first World War, Zeiss had a dominating interest in the German optics world, controlling every facet of lens construction, from the mixing and melting of sands and materials to make every kind of glass imaginable, to the construction of telescopes and eyeglasses that bore the Zeiss name.

As Germany entered the war, Zeiss, along with many other German optical companies took on lucrative contracts with the German military, making all sorts of war time optical products. As the war ended and Germany’s economy fell into ruin, many of these smaller companies struggled, some even closing their doors for good.

In 1926, at the suggestion of the German government, Zeiss would take control over four of Germany’s leading optics companies, Ica, Ernemann, Contessa-Nettel, and Goerz, and form Zeiss-Ikon.

A condition of the merger, the German government insisted that none of the plants from the original four companies be closed, nor any employees laid off. Zeiss-Ikon had the dubious task of finding a way to integrate dozens of similar photographic products and lenses, along with lesser known products like automotive lamps, key lock systems, and light bulbs, into a single cohesive catalog.

The first couple of years of Zeiss-Ikon’s existence saw a lot of change between the 4 original companies and Zeiss’s original staff, with some notable casualties such as the ousting of August Nagel, who had worked for Contessa Nettel prior to 1926.

By 1930, a majority of cameras were still of the bellows or rigid box types, using medium and large format roll and sheet film, but there was a new type of camera that was gaining popularity, a “miniature” camera that used 35mm double perforated “kine” or cinema film. Although 35mm cinema film had been in use by the motion picture industry for quite some time, smaller companies had experimented with making still photograph cameras using surplus cinema film that was widely available. The comparatively small sizes of the 18mm x 24mm exposures that these cameras made were considered too small for serious photography, and required the extra step of enlarging, which added cost, before a usable result could be had.

At this time, the very large and very powerful Zeiss-Ikon did not have the luxury of innovating in what many at the time considered a “fad” format of film, but a smaller company that specialized in microscopes from Wetzlar, Germany, named Ernst Leitz did.

In 1912, a Leitz designer named Oskar Barnack was working on a new 35mm cinema camera and he needed a way to reliably test strips of 35mm cinema film for proper exposure. Rather than run the film through a cinema camera, wasting multiple frames for a simple test, Barnack created a simple device that exposed a single image on 35mm film which could then be developed to determine the proper exposure for that same film in his cinema camera.

At first, Barnack’s 35mm cinema film tester was just a one off device that was never meant to serve any other purpose than what he created it for. In fact, Barnack’s invention would sit on a shelf in his workshop for nearly a decade before anything more would come of it.

In the 1920s, as the German economy struggled, Leitz was one of those companies that needed a way to stay profitable, and in a move that would later prove to be one of the most significant in the entire history of photography, company president Ernst Leitz II suggested that Barnack’s single film tester be designed as a new type of miniature 35mm still camera. As many as 25 early prototypes of the new Leitz camera, which was given the name, Leica, were produced and handed out to local photographers to gauge their interest.

The feedback was immediately positive, and it gave Leitz the incentive to go ahead and begin production of their new Leica camera. The Leica was revealed in 1925 at the Leipzig Spring Fair in Germany as the Leica I. The camera was an immediate success as it was the first ever compact camera designed for 35mm cinema film made with top notch quality, by a reputable optics company as opposed to some hobbled together model built with very low quality control standards.

Over the course of the next few years, the Leica’s reputation grew, spawning many less expensive copycat cameras by a variety of companies, except Zeiss-Ikon. Preoccupied with their consolidation of it’s various firms and product offerings, Zeiss-Ikon was slow to produce a response. In a half hearted attempt to produce a compact camera, but without having to design something from the ground up, in 1930 the Zeiss-Ikon Kolibri was released. It was a compact and portable camera that shot 3cm x 4cm images on 127 “vest pocket” roll film. It did not sell well. It would take another two years before Zeiss-Ikon would produce a sufficient response with the Contax.

The original Contax was a very ambitious camera. With an interchangeable lens mount, a huge selection of lenses, and a coupled rangefinder, meant it could go head to head with the Leica. The Contax also featured many firsts such as an entirely removable back for easier film loading and a vertically traveling metal shutter with a top shutter speed of 1/1000.

All was not well however. The Contax was large and very heavy, and with a brick-like shape with sharp corners, it had poor ergonomics and was not as pocketable as the Leica with it’s round edges and excellent handling. But the worst part was that the Contax’s innovative shutter was notoriously unreliable, causing many Contaxes to develop problems shortly after coming out and the camera earned a poor reputation among pros and camera repairmen alike.

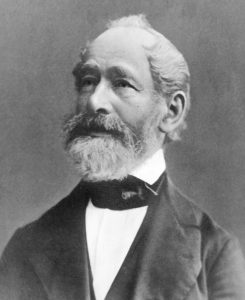

Contax knew they had to act quickly, and a redesign of the Contax was ordered. Zeiss-Ikon president Dr. Heinz Küppenbender tapped the mind of a young Zeiss engineer named Hubert Nerwin who had previous design experience working for IBM and Siemens. Nerwin worked on a number of Zeiss-Ikon designs in those days, and his superb understanding of ergonomics and what professional photographers wanted, allowed him to quickly move up the ranks.

Küppenbender saw the potential in Nerwin and in 1935 appointed him as head of design. In this position, Nerwin aided in the design of the Contax II, Super Nettel, Super Ikonta, Nettax, and Contaflex TLR. The redesigned Contax II was a huge success, as were the other designs that Zeiss-Ikon produced under his watch, but for as great as they were, they all were projects either started by someone else, or had elements that weren’t entirely from Nerwin’s mind. It was time for Hubert Nerwin to create his own camera from scratch.

Around 1934 or 1935, Hubert Nerwin would start on a concept that would become the Tenax, a camera that emphasized speed and convenience over anything else. Everything about the camera would be entirely new, except for the name which was borrowed from an unrelated line of Tenax roll film cameras produced by Goerz as recently as 1926 when they merged to create Zeiss-Ikon. It is unclear how much of Nerwin’s day to day time was spent designing the Tenax, or if it was a pet project that he worked on in his spare time, as it would take nearly four years before the camera would make it’s release in 1938.

For his new camera, Nerwin wanted it to be compact, have fast and intuitive handling, interchangeable lenses, and be of the highest quality. It is unknown which, if any, of these priorities took precedence over the other or if they all just came together at once.

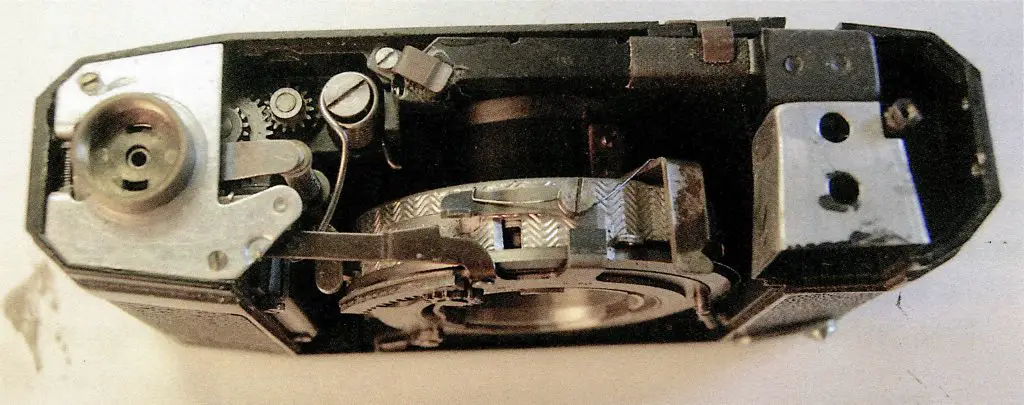

Nerwin’s choice of a leaf shutter was likely a result of the less than stellar reputation of Zeiss-Ikon’s own vertically traveling focal plane shutter used in the Contax and other 35mm cameras. Although not produced by Zeiss-Ikon, the Compur Rapid shutter was built by Deckel of Munich, who Zeiss-Ikon had a controlling interest in, so it was a logical selection.

The shutter used in the Tenax is a Type 0SR Compur Rapid shutter, which was normally used in medium format cameras, as opposed to the Type 00 shutter which came in most leaf shutter 35mm cameras.

The issue with the Type 00 Compur shutter is that it’s overall opening was too small to allow for lenses any faster than f/2.8 to be used as the shutter itself would cause vignetting with anything faster. The Type 0SR shutter had a larger 25mm opening which would easily allow lenses as fast as f/2 to be used. It’s biggest downfall was that it’s maximum speed was 1/400, instead of 1/500, which Nerwin must have seen as an acceptable compromise.

Even with the larger opening, the Type 0SR shutter would have made it difficult to design front mounted lenses that would also cover a full 24mm x 36mm frame. The problem would get worse with longer telephoto lenses so the decision was made to reduce the size of the exposed image to 24mm square, a size also shared by the Berning Robot camera.

Another advantage of 24mm square images, instead of more standard 24nm x 36mm images, was that it allowed for shorter focal length lenses to be used. By using a 40mm standard lens instead of a 50mm one like on most other 35mm cameras of the day, allowed for greater depth of field, and physically smaller lens elements that not only kept the size of the camera and it’s lens small, but also meant it could be produced at a lower cost, making the camera more affordable, without compromising quality.

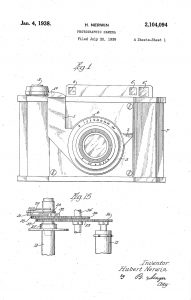

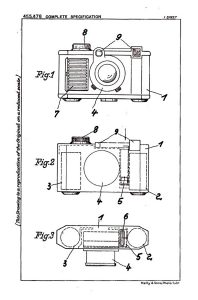

By July 1936, the first patents of the Tenax began to appear, and the camera already had the 24mm square film gate, rangefinder, Compur Rapid shutter, and the vertical lever that controlled film advance and shutter cocking in one motion.

Keeping with his theme of making the Tenax fast and intuitive, it had a number of other features that might have been taken for granted 5-10 years after it’s release, but were pretty cutting edge at the time. A combined coincident image rangefinder was a huge convenience and one that many lesser rangefinder cameras did not yet have. Kodak had only recently released their new type 135 pre-loaded 35mm cassettes in 1934, and the Tenax offered full support for them, plus the ability to rewind film at the end of the roll. A quick change bayonet lens mount, a single filter size for all available lenses, and uniform spacing of the aperture ring showed an attention to detail and an understanding of what photographers needed.

In total, four lenses were produced for the Tenax, a 2.7cm f/4.5 Orthometar, a 4cm f/2.8 Tessar and a 4cm f/2 Sonnar, and a 7.5cm f/4 Sonnar which compare to 34mm, 50mm, and 94mm on a 24×36 camera. Prototypes for a 4cm f/3.5 Triotar, a 4cm f/3.5 Tessar, and a 3.5cm f/2 Biotar were created for the Tenax, but never mass produced.

The camera would make it’s debut in April 1937 at the Leipzig Trade Fair in April, and for the North American market in September. Although known today as the Tenax II, it came before the Tenax I, which made it’s debut in 1939. The Tenax I is an almost completely unrelated camera, with a totally different body, simpler construction, no rangefinder, a fixed Zeiss Novar or Tessar lens, and a Compur shutter with a maximum speed of 1/300. The only similarities between the two are the shared 24mm square images and a similar rapid film advance cocking lever on the camera’s right side.

The Tenax II was produced at the former Ica factory in Dresden and was heavily promoted by Zeiss-Ikon through 1942, but production of the cameras stopped sometime in early 1940 to make room for wartime production.

In the United States, the Tenax II sold with the Sonnar f/2 and Tessar f/2.8 lenses for $207 and $171 respectively, which when adjusted for inflation, compare to $3165 and $3800 today, making it quite an expensive camera.

Although warmly received, it is estimated that between 8200 and 8500 Tenax IIs were produced in the years 1937 through 1940. This is in comparison to the more basic Tenax I, of which 30,000 were made, and the Contax II and IIIs which had even higher production numbers. The Tenax II was definitely a niche market camera, but it not only met every requirement of Hubert Nerwin’s original vision of a fast and intuitive camera, but it featured a combination of features that no other camera would have. Who knows what might have happened had the war not happened and production continued into the 1940s when more people would become interested in photography.

According to an article in 1985 by Nerwin himself, a Tenax III was planned, possibly even to be concurrently released with the Tenax II, that would have come with some type of coupled exposure meter. In this article, Nerwin suggests that the body of the Tenax II was designed from the very beginning to have enough space for an exposure meter to be added later. Prototype drawings from 1936 show a Tenax shaped camera body with a rectangular meter on the front of the camera’s body, where the Tenax film advance lever is. This location for the meter meant that the overall size and shape of the camera would be unchanged, unlike other cameras like the Contax III that required a large protruding exposure meter sticking out of the top plate.

A later prototype clearly shows a Tenax II with the film advance lever relocated to the side of the camera, similar to the one on the AGFA Karat series. This prototype doesn’t feature the meter, but it’s not a stretch of the imagination to picture a Tenax II style body, with a body mounted exposure meter in place of the film advance lever and a new lever on the camera’s side. Sadly, the Tenax III only exists in vague drawings and in the minds of collectors like myself. Zeiss-Ikon’s obligations to the German war-effort thwarted any progress on such a camera.

Production of the Tenax II never resumed after the war, but the simpler Tenax I did. The camera would go through some minor variations and in 1953 would be renamed the Taxona as the East German Zeiss-Ikon had lost the legal rights to the name Tenax. The Taxona would stay in production until about 1959.

In 1960, the Tenax name would be recycled once again by Zeiss-Ikon of Stuttgart, West Germany in a completely unrelated camera. This new Tenax would shoot regular 24mm x 36mm images in an entirely new body with a large, scale focus viewfinder, and would feature automatic exposure through a coupled selenium exposure meter.

Today, the original Zeiss-Ikon Tenax II is a highly sought after camera, not only for it’s rarity, but also it’s unique looks and combinations of features. Michael Wescott Loder has taken an interest into this camera, writing a highly detailed historical book about it. Although it didn’t sell very well when it was first built, it was ahead of it’s time in terms of speed and simplicity. Shooting one today is quite simple and assuming the camera is in good operating condition, is capable of wonderful results.

My Thoughts

This Tenax II was kindly loaned to me by collector Michael Wescott Loder, who is the author of the excellent book “The Tenax II: Zeiss Ikon’s Precision, Fast-action Camera”. Wes is also a big Nikon fan and while collaborating with him on another article, he asked if I’d ever be interested in trying out a Tenax II. Having only been mildly familiar with the lower end Tenax camera, I was fascinated by it’s big brother and gladly accepted.

With the camera, came two lenses, the 4cm f/2 Sonnar, a telephoto 7.5cm f/4 Sonnar, and a copy of his book which was a huge reference for the information in this article. Normally when attaching anything but the 4cm standard lens, an auxiliary viewfinder would be needed to correctly compose with the lens’s focal length, but not having access to one, meant I wouldn’t accurately be able to frame with it, so I didn’t shoot any images with the 7.5cm lens.

Having been designed by Hubert Nerwin, who also created the Contax rangefinder, the Tenax II shares some of the same visual cues. The overall shape and size of the body, the location of the viewfinder, even the knobs show some similarities.

Up top, going from right to left is the combined exposure counter and cable threaded shutter release button. It’s hard to see, but two red dots exist inside of the shutter release button that are markers for locking the shutter release for Timed exposures. To use this feature, first activate the film advance lever, then set the shutter speed to Bulb, and then press and hold the shutter release to open it, and while still holding it down, make a clockwise twist with your finger as far as it will go. This will lock the shutter open for as long as you leave it in this position. To close the shutter, twist the shutter release button in the opposite direction. This Timed shutter mode is not obvious to the casual observer, and I wonder if there are at least a few Tenax IIs that have been sold with an inoperable shutter, when in reality, it was just locked open.

Since the Tenax shoots 24mm square images, you’ll get more exposures per roll than a “full size” 35mm camera. As a result the exposure counter goes from 0 – 49, suggesting that 50 frames are possible on a 36 exposure roll of film. Although I can’t confirm this, I am sure that with careful loading of the film, an extra exposure or two is possible on the film leader, allowing for 51 or even 52 shots.

To the left of the exposure counter is a small chrome rewind release button and in the middle of the camera is the accessory shoe. Inside of the shoe is the camera’s serial number. Like they did with the Contax, the first letter of the serial number can be used to date when the camera was built. In this case, the letter “H” means this camera was produced in 1938. Earlier cameras produced in 1937 have a few minor cosmetic differences and have serial numbers that begin with the letter “E”.

On the left side of the top plate is a two piece rewind knob with a flip up handle. With the handle in the up position, it is a little easier to grip for rewinding the film, but still not as fast as cameras from later in the 20th century that can be rotated with a spinning knob. This style of handle was used on other Zeiss-Ikon roll film cameras like the Super Ikonta, and other 35mm cameras like the Voigtländer Prominent, but I have not seen it on other 35mm Zeiss-Ikon cameras.

Flipping the camera over, and we get the most “Contax-like” view of the Tenax II. Using the same kind of rotating door locks that allow reusable Contax style film cassettes, the Tenax II allows for a cassette to cassette film transport.

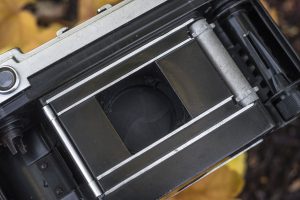

With the back off, we see the most distinctive view of the camera, which is it’s 24mm x 24mm square film gate. The body of the Tenax is wide enough to accommodate a full size 24mm x 36mm film opening, but Hubert Nerwin’s priorities when designing the Tenax necessitated the smaller square format. In the image to the left, you can see the removable take up spool, but a take up cassette may also be used.

Up front, the Tenax looks unlike almost any other camera made. A critical aspect of the Tenax II was that it needed to be fast in use. One of the ways in which Nerwin aimed to meet this goal was via a quicker way to advance the film, move the exposure counter, and cock the shutter all in one swift motion. While this was fairly common to see on 35mm cameras by the mid 20th century, in the mid 1930s when the Tenax was being designed, this was not common. Most medium format cameras still required the shutter be cocked in a separate step from advancing the film, and 35mm cameras like the Leica and Contax rangefinders were only marginally faster with their tiny knobs that often required the camera be removed from the eye to advance and set.

Nerwin’s solution was a clever front mounted film advance plunger that predated a similarly designed one in the Konica III from the 1950s, in which the trifecta of film advance, exposure counter change, and shutter cocking is done in one swift motion. Although this lever could be easily located with your right index finger, on the example I had, the camera was a bit stiff and required a little more force than I would have liked for a 80 year old camera, but most likely this is normal for all Tenax IIs. I found that by using my right thumb to press down on this lever was a bit easier, but required a reposition of my right hand each time I wanted to prepare for my next shot, somewhat negating the speed of which the camera was designed for.

Above the 12 o’clock position of the lens is the lens release for the interchangeable bayonet lens mount. Pressing down on this lever while giving the lens and rangefinder prism window a clockwise twist, easily removes the lens, revealing the large Compur leaf shutter behind it. Installation of a new lens is as easy as lining up two red dots near the 11 o’clock position of the lens and then twisting until the two rangefinder windows line up.

Each lens available for the Tenax is unique in that they each have their own front rangefinder prism and depth of field scale that is unique to each lens. I am not aware of any third party lenses available for the Tenax II, likely because of the complexity of these extra parts. In the image to the left, you can see both the 4cm and 7.5cm Sonnar lenses that I had access to with this camera.

The viewfinder is large and unusually bright for a 35mm rangefinder camera from the 1930s. Considering many cameras of the era like the Contax and Kodak Retina series used rear eye pieces barely larger than a piece of rice, the bright and roomy viewfinder on the Tenax II is easy to use, even with prescription glasses. The coincident image rangefinder patch takes on a pinkish hue and is contrasty enough to use in all but the darkest light.

The Tenax II, despite it’s non-standard appearance has all of the features that you’d expect of a quality 35mm rangefinder camera built by Zeiss-Ikon, there’s even a self timer which has an inscribed Compur Rapid logo on it.

Hubert Nerwin’s influence on this camera is undeniable and it is clear that the man had a lot of great ideas about what a quality 35mm camera should be. The fact that nearly the entire camera had to be developed to meet his vision, rather than be built upon off the shelf parts is even more impressive.

The Tenax II is beautiful camera, and looks great on paper, but how is it to use?

My Results

For the first roll of film through the Tenax II, I loaded up some expired AGFA APX 25. This is a slow speed black and white film that ages well and at ASA 25 is consistent with slow speeds that would have been available when the camera was new. I’ve previously shot this same film in my Nikon S2, so I knew what to expect.

Shooting the Tenax II was uneventful, but in a good way. Often when shooting pre-war cameras, there are various concessions or quirks that must be made to accommodate how things used to be. Maybe there’s a strange shutter advance process, or an interlock that must be manually released after each frame. Double exposures are often a risk on pre-war cameras, and in the case of rangefinders, separate viewfinder and split image rangefinders were the norm.

Not so with the Tenax II. The greatest compliment that I can give an 80+ year old camera is that it was uneventful because of how modern it is. Peering through the large and bright viewfinder with the combined coincident image rangefinder, the only thing that suggests you’re not shooting a 1950s rangefinder is the square frame.

Although the film advance was a bit tight, it worked flawlessly. Looking at the developed film, frames were perfectly spaced with little to no variance from the beginning to the end of the roll. The Compur shutter fired at all speeds, even down to 1 second with an accuracy that is as good as any other I’ve heard using my unscientific ear.

Upon looking at the negatives, two issues became clear. The first was a bit of haze inside the 4cm Sonnar. While haze is something that happens to many pre-war lenses, I’ll admit to not noticing this prior to shooting the camera. AGFA APX 25 isn’t normally a contrasty film, and with my preference for HC-110b which can subdue contrast, I wound up with many images without much pop. Had I been aware of the haze, I might have tried a higher contrast film that could have compensated a bit.

The other issue is one that Wes warned me about which is that the Tenax II doesn’t get along perfectly with modern 35mm film cassettes. Wes mentions this on pages 80 and 81 of his book, “The Tenax II: Zeiss Ikon’s Precision, Fast-action Camera“, saying that modern 35mm cassettes do not sit high enough on the film fork requiring a very firm push on the cassette prior to reattaching the back. Wes suggests that Kodak cassettes seem to sit better than Fuji ones. Based on my experience with the AGFA film, it would seem they sit the same as the Fuji as the exposed images overlapped one set of perforations throughout the entire roll. Below is a strip of the developed film to see exactly how the images were exposed. In the gallery above, I could have very easily cropped the sprockets off, but I left them in for effect.

Hazy images and a surprisingly modern shooting experience that gave me little to comment about aside, I quite enjoyed the little Tenax II. I’ve always found that composing images in a square frame forces you to look at things just a little different. I’m going to compose my images in a 6×6 TLR differently than a 6×9 camera, and that still applies with smaller 35mm film. I can’t really say that I nailed it on any of my exposures here, but I’ve seen it done with great success by other people.

Hubert Nerwin aimed to create a camera unlike any other, with features that would make it fast and easy to use and he absolutely succeeded. I can’t help but wonder what might have come from future development of this line of cameras had World War II not intervened. Would more companies have created square format, rapid cameras like the Tenax? Would Nerwin have stayed with Zeiss and not left for America? Who knows.

I am very grateful to Wes for letting me borrow his camera and read his book. This is a fantastic camera worthy of addition to any collection. It’s a well built and gorgeous camera designed by one of the premiere designers of the 20th century, and one I hope to add to my permanent collection someday.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Tenax_II

http://elekm.net/pages/cameras/tenaxii.htm

http://wesloderandnikon.blogspot.com/2013/11/the-tenax-ii-zeiss-action-camera-from.html

Another brilliant review. How do we get Wes Loder’s book?

The Tenax book is available to order via your local bookstore (through Ingram), or via Amazon. The soft cover version sells for $35.89 on Amazon is what I would recommend. Cheers, WES

Mike, as usual, another fascinating review. I’d always wondered why Zeiss chose the strange 24mmx24mm format, for what was a very expensive camera in its day. Now I know.

The “rapid” lever style was also adopted for the English Agimatic c.1958/9 but it was taken a stage further in that it became a four-function operation in that it advances the film, cocks the shutter, advances the frame counter and then in the final part of its throw, fires the shutter.

One final comment, did you really mean to say that the Contax 1 can’t rewind an exposed film? As you know, I recently acquired an almost pristine and fully working Contax 1, v.7 and this has a rewind knob, so I’m assuming all the models do. Whilst they do have cassette to cassette use, with the appropriate re-loadable cassettes (when of course rewinding isn’t necessary) they can still take conventional 35mm cassettes.

You got me. Having never handled the original Contax, I got confused by something I read that stated Zeiss improved support for 35mm film in the later Contax II and I misinterpreted what I read. I have corrected the article.

Very interesting review of a camera that has always interested me, due to the square format. Makes a fellow wonder if a Tenax II was sitting on a drafting table at the Konishiroku Works in 1956 while the Konica III rangefinder was being designed!

Great review with lot of information, managed to find one and is on it’s way. May I ask for the len thread size and len cap size for Sonnar 40mm F2? Any any camera case recommend for it? Wanna get some protection ready before it arrives. XD

I purchased a Zeiss Ikon 35mm tenax 2at a local yardsale for $5. overall the camera is in very good shape with clear lense optics and all the controls seem to work. What I so far have figured out is how does the camera open up to load film into it?

I purchased at a local yard sale a ca 1939 Zeiss Ikon tenax 2 for the price of $5. Overall it is in very good condition with clear lense optics and in good operating condition. I would like to know how you open up the camera to load film in it.