This is a Bell & Howell Autoload 342, a compact camera made by Canon of Japan that used Kodak’s type 126 Instamatic film cassettes. The Autoload 342 had an innovative Focus-matic system that used a delta rangefinder that worked using a moving ball bearing that would trap the focus distance of the lens depending on the angle of the camera to the ground. This type of mechanical auto-focus is unique to this camera and it’s predecessor, the Autoload 341. In addition to the Focus-matic system, it had a battery powered motorized film advance and fully programmed automatic exposure, making for a very capable camera.

Film Type: Kodak Instamatic Type 126 Cassettes

Film Type: Kodak Instamatic Type 126 Cassettes

Lens: 40mm f/2.8 Bell & Howell coated 4-elements

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity, Focus-matic Delta Rangefinder System

Viewfinder: Reverse Galilean Viewfinder with Projected frames

Shutter: Copal Electric Leaf

Speeds: 1/30 – 1/800 seconds

Exposure Meter: Full Program AE with Viewfinder Readout and Overexposure Indicator

Battery: 2 x 1.5v AAA

Flash Mount: Flashcube Socket

Weight: 373 grams (without batteries)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Bell & Howell Autoload 342 is an unassuming Instamatic film camera built by Canon and sold in the United States featuring a nicely designed body, a quality 4-element Canon lens, auto exposure, and a motorized film transport. But it has one feature others don’t, a unique Delta Rangefinder focusing system which they called “Focus-Matic” which uses a rolling ball bearing that changes position depending on the angle the camera is to the ground. As strange as this sounds, the system actually works quite well, and I was able to shoot many properly focused shots with little difficulty. This isn’t a common camera, and most people don’t want to deal with the challenges of shooting an Instamatic film camera these days, but if you’re interested, there weren’t many other cameras like this one. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for innovative delta rangefinder and unexpected overall quality | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

In the decade following World War II, the Japanese optics industry very quickly proved that they could make some really terrific products. Companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), Asahi Kogaku (Pentax), and Canon released an onslaught of excellent cameras, lenses, and other devices. The problem they had however, was that they could make the products, but they had a difficult time selling the products, especially in the United States where the photographic buying public was still very much in love with German made cameras and lenses.

To help them get their products on store shelves and into the hands of consumers, these companies relied on exclusive distributors in the United States like Joe Ehrenreich and C.R. Skinner were largely responsible for bringing Nikon and Canon cameras to the United States. Other companies forged relationships with US companies like the Sears Roebuck & Co. (Tower) and Montgomery Wards to sell house versions of their products. Pentax cameras were sold by Heiland and Honeywell, and in some cases, Japanese cameras were developed specifically for the American Market (Anscomark M).

In 1961, in an effort to gain a stronger market share in the United States to compete with Nikon, Canon came to an agreement with Chicago based Bell & Howell to distribute many of their SLR and rangefinder cameras in the United States. Bell & Howell was already an established and respected maker of motion picture cameras, and by the late 1950s had seen their sales declining. Sensing a need to expand into the still photographic market, the marriage of Canon and Bell & Howell seemed mutually beneficial to both companies.

Over the next few years, Bell & Howell branded versions of the Canon FX and EX EE SLRs, Canonet rangefinders, and Demi and Dial compact cameras were sold in the United States. Other than the appearance of the Bell & Howell name, each of these cameras were identical in every way to their Canon branded counterparts.

In 1969, for reasons I was never able to conclusively discover, Canon decided to release three new cameras exclusively under the Bell & Howell name that were not a simple rebadge of an existing model. The three cameras were the Bell & Howell Auto 35 / 2.8, the Autoload 341, and the Autoload 342. The first model, would be a variant of the Canonet 28, but would contain a new “Focus Matic” feature that the Canon Camera Museum described as “Bell & Howell’s needle-aligning delta rangefinder”.

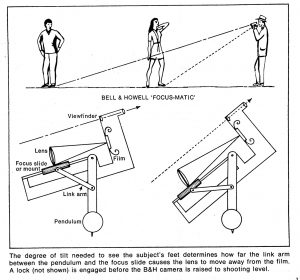

This new feature would be included in all three of these models and would be an interesting new take on focus assist. Although still technically considered a rangefinder, instead of using optics through two windows, it used a moving ball bearing which would roll across a track depending on the angle of the camera in relation to the ground. When the camera was parallel to the ground, the ball bearing would be in it’s farthest back position and would indicate a focus distance of infinity. To measure the focus distance of your subject, there was a horizontal line in the viewfinder that you were supposed to aim at the base of whatever you were intending to photograph. If you wanted to photograph a person standing 8 feet away, you would tilt the camera down, until the line in the viewfinder lined up with the feet of the person and a needle visible in the viewfinder would indicate 8 feet. You would then manually turn the focus ring on the front of the lens to 8 feet. As you tilted the camera at an angle toward the ground, the bearing would roll forward, shortening the focus distance all the way to the camera’s minimum focus distance.

On the Auto 35 / 2.8, the Focus Matic system would display it’s reading as a match needle which you would then manually turn the focus ring on the front of the camera to match the detected distance, then you would recompose your image so that your intended subject was in the viewfinder, and you’d press the shutter release.

The second model in the series, the Autoload 341, used the same delta rangefinder system, but this time in a camera that used Kodak’s Instamatic 126 film system. Both cameras had nearly the same feature set, including full programmed automatic exposure, but instead of the detected focus distance being displayed within the viewfinder like on the Auto 35 / 2.8, it was seen through a window on the side of the camera.

The final model, the Autoload 342 used the same Instamatic 126 film as the Autoload 341, but was a much more advanced camera. Still featuring full program automatic exposure and the Flashcube system, the Autoload 342 added a fully motorized electronic film transport, thus eliminating the film advance lever of the two other models.

The biggest change however, was in how the delta rangefinder system worked. The camera still had a horizontal line in the viewfinder which required you to tilt the camera down to the base of the intended image, but once you obtained your desired distance you’d press down and release a lever on the side of the lens to “trap” the bearing at the selected distance and automatically move the lens to focus to that distance. After releasing the lever, the focus distance is locked in and you were free to recompose your image at any angle without losing the detected focus distance.

The whole delta rangefinder system is mathematically sound, but has several significant limitations. The most obvious is that it requires that the subject and the photographer are on an even plane with the camera at a predetermined distance off the ground. If you try to shoot an image of something at an upward or downward angle, or if the photographer is especially tall or short, the math won’t check out. Further evidence of my skepticism of this system is that no one ever used it on another camera.

When used to it’s strengths, it does work, but I just can’t understand why it was invented at all considering optical rangefinders had been in widespread use since the 1930s.

In the ad to the right from May 1970, the Autoload 342 is said to have a retail price of “less than $88” which probably means $87.95 or something similar. When adjusted for inflation, this compares to about $540 today.

In my research for this article, I found no period articles or reviews from either Canon or Bell & Howell suggesting what it’s intended market was for. Was this seen as a stopgap measure for automatic focus? Was it an attempt to stand out in a very crowded camera market near the end of the 1960s, or did some designer who was dating the daughter of some vice president convince the right person to try his or her bizarre idea in the public market?

Who knows what really happened. All I can say with certainty is that it did happen, and these cameras do exist as evidence. Today, I doubt many people even realize that there’s something unique about any of these three models. By 1969 and into the early 1970s, inexpensive Instamatic cameras with the word “auto” in their name were extremely common. A look on eBay or thrift stores show a dizzying number of models made by nearly every camera manufacturer in the world at that time. Unless you’ve actually handled one of these cameras (or have read this article), I’d be willing to bet that they slip under the radar of 99% of collectors out there.

My Thoughts

The methods employed by camera makers in the 20th century to assist with focus are numerous. From uncoupled rangefinders to fully automatic computer controlled automatic focus systems, people have always been looking for ways to accurately focus their cameras.

When I first heard about the mechanical “Focus-matic Delta Rangefinder System” on the Bell & Howell Autoload 342 from my friend Adam Paul, I was skeptical. It just sounded too bizarre to be useful, but if there’s one thing I like about reviewing old cameras, are ones with strange quirks or unique features, and this one certainly is strange.

As often happens, no sooner did I express an interest in checking out one of these cameras “someday”, a package arrived on my doorstep from Adam, with one inside. I eagerly opened the package and inspected it.

For starters, the Autoload 342 is quite a sleek camera. There is quite a bit of plastic, as was typical of cameras of it’s era, but the camera does not feel cheap. I didn’t bother to disassemble the camera, but it feels as though there is some inner metal chassis surrounded by plastic, but it’s a good plastic, and doesn’t creak in your hands. The camera is also more compact than other ‘premiere’ Instamatic cameras like Kodak’s own 700 and 800 series cameras which have the sharp edges of a 1960s Argus C3.

The top plate is quite sparse, featuring the Flashcube socket, black shutter release button, and cable release socket behind it. The Autoload 342 is an entirely automatic camera with no manual shutter speeds or f/stops. Your only control over how the camera functions is the little lever in front of the flash socket, which has two settings, “EE” and “Flash Zone”. Both modes are fully automatic, with “EE” reserved for flash-less photography, and “Flash Zone” for using the flash. I could not find any resource showing the camera’s user manual online, but while playing with the camera in flash mode, the auto exposure system seems to still be enabled, but it looks like the aperture is coupled to the focusing distance. It stops down for close ups, and opens wide for farther away shots, which is consistent with how flash modes worked on many other early auto exposure cameras.

By far, the most interesting thing you see looking down upon the camera is the focus distance scale, which is coupled to the Focus-matic Delta Rangefinder System. I explain how this works above in the History section, but in case you didn’t read it there, it works by tilting the camera forward to align a horizontal line in the viewfinder with the lowest point of whatever you want to photograph. Once you have the camera in the correct tilted position, press and release the black lever on the side of the lens to lock in the focus distance. With the focus locked, you can recompose your image in the viewfinder to suit your needs without losing your focus distance.

For shots where your subject and you are on the same horizontal plane this actually works very well. I found that while shooting, the motion of tilt, focus, raise, shoot was actually quite fast. I am often slowed down more by tiny optical rangefinders in which I have to first find a suitable vertical line to align the two images with and then recompose my shot.

The problem with this system though is that it only works when shooting something on the same horizontal plane as you. Try to shoot something at an upward or downward angle and forget about it.

Like nearly all 126 Instamatic cameras, there is no exposure counter anywhere on the camera. Instead, you read exposure numbers off the film’s backing paper which can be seen through a rectangular window on the back of the camera. In the image to the left, I do not have film loaded into the camera, but normally you would see a series of numbers indicating which exposure you are on. If you see X’s in the window, then it means you’ve reached the end of the film.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and the battery compartment door for two AAA batteries. It’s a minor thing, but I appreciate that the AAA batteries power both the motorized film transport and the flash as it was common for many cameras of this era to have a separate battery compartment just for the flash and another for the rest of the camera. Plus, AAA batteries are still common today, so hunting around for an obscure PX825, PX640, or type-K battery is not necessary to shoot this camera.

Loading film into the camera requires releasing a small catch on the camera’s right side, and then the left hinged door swings open. As with all Instamatic cameras, a new cassette simply snaps into position without requiring any additional steps. Upon closing the door after inserting a new cassette, the camera will automatically transport the film to the first exposure.

With the camera loaded up and ready to shoot, your next impression comes from the viewfinder which unlike many lesser Instamatic cameras, is not only large and bright, but offers information about the camera’s detected shutter speed, along with overexposure and flash ready indicators. The horizontal line through the middle of the image is used for the Focus-matic system which I covered earlier in this review, and near the upper corners of the projected frame lines are parallax correction marks for exposures less than 5 feet away.

I felt pretty good that I understood how the focusing on this camera worked, and with a reasonable certainty that the meter and shutter were working correctly, I decided it was time to load it up and shoot with it. But you can’t buy fresh Instamatic film anymore, so what did I do?

My Results

Not having access to any viable Instamatic film, I tried my hand at reloading an empty one with some regular 35mm Fuji 200 film. My friend Adam Paul is an avid 126 shooter and has reloaded many cassettes for cameras in his collection, so he gave me a tip that some Instamatic cassettes are easier to load than others. He said Kodak and Fuji cassettes are usually the most difficult as they are glued shut and often break when trying to separate the two halves, but those made by GAF, AGFA, and many “white label” cassettes are easier to take apart. Using his advice, I cut an appropriate length of film, and taped it to the backing paper of the original film doing my best to line up the film and the paper and rolled it back into the cassette…all in complete darkness.

There are a variety of articles online showing you how to load regular 35mm film into old Instamatic cassettes or the 3D printed Fakmatic 126 Adapter online, but I found a better way. If you’d like to know how I did it, check out my article, Reloading Instamatic Film (The Better Way).

After successfully getting through that first roll and seeing the color shots, I tried it again with some bulk Kodak TMax 100 which are also included in the gallery below.

Upon seeing the film after scanning, my first reaction was, “Yay! I loaded the film correctly!” If this is the first time you’ve seen 35mm film loaded into an Instamatic camera, the positioning of the sprocket holes through the top of the image is perfectly normal. While Instamatic film is physically the same width as 35mm, it does not use the same layout of sprocket holes. There is only one single perforation per frame, near the bottom of the image (actually the top of the film, as the camera inverts the image upon exposure). You’ll also notice in several of the images there is some overlap between exposures. I have seen this on almost every example of someone running 35mm film through an Instamatic camera, so I guess that’s a normal side effect of using film in a camera that it wasn’t designed for.

My second reaction was, “Wow! The Focus-matic system actually works!” I’ll admit to not trying any extreme closeups, but many of these images were shot at less than infinity and I was pleased to see an entire roll of in focus shots.

Beyond that, I was a little disappointed in the outcome of the exposures. Although I used fresh Fuji 200 film, exposure seemed to be off on most of the shots and colors were pretty muted. Every image in the gallery above has some level of Photoshop tweaks performed to get the images you see. I’m not too bothered though, but perhaps for my next roll through this camera, I’ll try different film.

Considering the highly experimental nature of this first roll, I’m extremely impressed at the results. Although the exposures were a bit off, the images are sharp and detailed without obvious optical anomalies like softness or vignetting at the corners, suggesting Canon did not skimp on the 40mm Bell & Howell lens. This is a fully automatic camera that relies entirely on a selenium exposure meter without any manual shutter speed or aperture settings. The Focus-matic system is unique to only a couple cameras ever made, and doesn’t exactly inspire confidence when you first learn how it’s supposed to work. On top of all of this, I had to manually reload a plastic cartridge that wasn’t meant to be reloaded with film that didn’t even belong in it, yet I got a whole roll of mostly usable shots.

I don’t expect many people reading this review will likely go out and buy a Bell & Howell Autoload 342 and jump through the necessary hoops to shoot one, so you’ll all just have to take my word that the Focus-matic system works surprisingly well. If it seems odd to have a separate step for detecting focus and then composing, I can think of many instances where I had to move a coincident image rangefinder around to find a suitable vertical line or orb to detect the distance and then recompose my shot in a separate step. The Focus-matic system requires that you move a horizontal line to the base of your desired image and back up again, which can be done in an instant. You don’t have to search around for something to line up two images on, and it works fine in low light. I found that while shooting outdoors, I was able to get used to this two-step motion quickly, and it only required a fraction of a second prior to releasing the shutter.

Yes, there were some instances where my subject was not on the same horizontal plane as myself, rendering the Focus-matic system unusable, but that only meant I was limited to using the camera to it’s strengths, which is something that when shooting old cameras, is done often. I can think of many classic film cameras I’ve shot where I had to think to myself, can this camera handle this situation? Using an old camera to it’s strengths is almost always a requirement and certainly not unique to the Bell & Howell Autoload 342.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://global.canon/en/c-museum/product/film73.html

http://www.eyescoffee.com/collectcamera/bellhowellautoload342/index.php

https://www.thephotoforum.com/threads/the-bell-howell-autoload-342.426010/

Well, Mike, you’re correct that this family of cameras passed under my radar lo these many years. I just took the easy way out, avoiding the 126 issue, and bought an Auto 35/2.8 from E-GAS. Lord only knows if it’s a functional camera – the listing has that dreaded wording “it worked fine last time we used it”. Thanks for this article – always good to learn of older innovative attempts to solve photographic problems.

I recall reading about Bell & Howell’s “footsie” focusing system in the photography magazines of the day. Aside from needing to be on the same level as your subject, this was for “still” pictures. (Sports? Nope. Fast moving kids? Nope.) I did hear the siren call of the 126 drop in film loading song and finally bought a Minolta Autopak 700. (The GAF Anscomatic 126 camera that you wrote about was unavailable by the early 1970’s.)

An unspoken problem with 126 was the “pillow shaped” film plane that all but guaranteed soft corners at large apertures, making f/2 lenses out of the question. Also, 126 was an ASA 80-125 format, which limited one to “bright days or flash” conditions.

The Minolta’s trapped needle autoexposure system required a long, stiff “Instamatic Jab,” which made 1/30 sec. exposure subject to camera shake, (I broke a fabric covered cable release trying to get a smoother result on a tripod mounted Autopak 700.)

All in all, 126 was successful in the mass market, but I went back to Ye Olde Leica IIIa, which “could do it all,” once I got an independent camera repairman to add 1/20 sec. X synch to it. I did look at the instamatic 500 with some longing, but decided to “keep it in budget” with the Minotla Autopak 700. The Kodak Instamatic Reflex was odd but interesting, though through-the-lens metering systems were the norm by the time the “Instamtic Retina Reflex” showed up.

I searched for Minolta’s Rapid 24 camera to see what the “European version” was like. It was OK…until wear on the felt lips on the metal Rapid cassette made them inoperable after 3-4 uses. The ASA was set by a tooth on the Rapid cassette, so one could “trick the system” into using something like Tri-X Pan with a longer stick. The 24X24 square images were corner-to-corner sharp, though the only film available at the camera store was made by Agfa. (Agfacolor 80 or Agfachrome CT-19, if memory serves.)

The Autoloading 35mm cameras made the 126 cassette system as up-to-date as the original 126 roll film, and then the Konica Autofocus 35 changed the market once again. A great article; I suspect that the Bell & Howell “Focus-matic” system taught some school kids about right angles.;)

Film flatness was definitely a problem for Instamatic cameras which was one more reason the pros hated it (there were many reasons), but for the average joe who only wanted a single speed point and shoot camera, it was certainly good enough. It seems that every attempt Kodak ever made to replace type 135 format film always had some level of compromise.

I’d like to get my hands on more 1960s Rapid cameras. The only one I’ve encountered so far was the Pentacon Penti which was a half frame Rapid camera. I know Minolta, Konica, Fujica, and other Japanese companies made some pretty interesting models.

Oops! I confused your article about the 1960 Ancomark M with the much later DAF Anscomatic 726.

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/GAF_Anscomatic_726

OK, so my Auto 35/2.8 Focus Matic arrived today. This is the 35mm version of the camera Mike reviewed. On this model, setting the film speed (on a range from ASA 25 thru 400) presets the aperture. The selenium meter sets the shutter speed. Well, at least that’s what’s supposed to happen: On my camera, the cell must be dead, as the Seiko shutter fires at one speed – about 1/30 – regardless of light conditions.

.

The Focus Matic system is pretty cool: Two pointers are visible along the right side of the viewfinder, a solid one which responds to the angle at which the camera is held, and a ring-shaped pointer that’s connected to the manual focus adjustment. In effect, you transfer the reading from the Focus Matic indicator to the lens by matching up the needles … not unlike using an accessory rangefinder with a scale-focus camera. Due to the meter/shutter speed issue, I think I’ll run a roll of ASA 50 film thru this camera, and tweak the exposure by changing the aperture via the ASA setting.

Roger! How cool that you got the 35mm version! I like how the measured distance is visible in the viewfinder, which is something the Autoload 342 can’t do. Your only indication of distance is on the top display! I am excited to hear about your results after shooting this camera. Even if the experience is clunky, Canon put a good lens on there, so you should definitely get some sharp images!