As I’ve done for the past 3 years at the end of April, I release a “Halfway to Halloween” post in my Cameras of the Dead series of 3 cameras that no longer work, but are worthy of mention.

Each year, I come up with some cheesy tie in to a horror film or franchise as I am as big of a fan of horror movies as I am cameras. This year, seems a bit different as I start writing this in late March and as I sit here in front of the computer, the world is under quarantine due to the COVID-19 pandemic that is far scarier than any movie, even one like Steven Soderburgh’s Contagion from 2011.

Each year, I come up with some cheesy tie in to a horror film or franchise as I am as big of a fan of horror movies as I am cameras. This year, seems a bit different as I start writing this in late March and as I sit here in front of the computer, the world is under quarantine due to the COVID-19 pandemic that is far scarier than any movie, even one like Steven Soderburgh’s Contagion from 2011.

This article should go live Tuesday, April 28th, which is a month away from when I write this, and I have no idea what the world will look like on that date. I don’t expect full normalcy by then, but hopefully things are better. They have to be.

If they don’t though, then I guess we can’t say we weren’t warned as ‘Contagion’ accurately predicted nearly everything that has happened since SARS-CoV-2 first broke out on China late last year. Lets hope that years from now, I can come back and read this article and think back “oh yeah, I remember that time, it sucked, but it got better”…

Mimosa II (1949)

This is Mimosa II, a 35mm scale focus camera, produced by VEB Mimosa Dresden starting in 1949. It was the followup to the original Mimosa, replacing the flip up metal viewfinder with a through the body optical viewfinder. Although resembling a box camera, the Mimosa is a quite compact 35mm camera that came with a variety of East German leaf shutters and lenses. The camera is notable mostly for it’s cube-like appearance, as it was quite a simple model. The Mimosa I and II were the only two cameras produced by it’s parent company, as in 1950 the company was absorbed into VEB Zeiss-Ikon.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.9 E. Ludwig Meritar uncoated 3-elements

Focus: Fixed Focus ~2m to Infinity

Viewfinder: Optical Scale Focus

Shutter: Velax Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/10 – 1/200 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 415 grams

Manual: None

My Thoughts

Who doesn’t like Mimosas?! A tasty alcoholic beverage consisting primarily of champagne and nutritious orange juice sounds like an excellent way to start every day.

Who doesn’t like Mimosas?! A tasty alcoholic beverage consisting primarily of champagne and nutritious orange juice sounds like an excellent way to start every day.

Oh wait, this isn’t that kind of Mimosa. Still, the Mimosa II is a distinct looking camera that once you see it, you’ll likely never forget it as there aren’t many other cameras like it. Speaking of how it looks, one thing that is not immediately apparent until after you see one in person, is how small they are. It’s cube-like appearance suggests something along the size of a Kodak Brownie box camera, but the Mimosa is quite a bit smaller than that.

The Mimosa was a minimalist camera built by a small East German company who was more famous for producing photographic paper and film than cameras, and it’s simplicity shows in it’s design, but not without a few surprises.

The first, is that despite it’s compact size, it shoots full size 24mm x 36mm images. In order to fit an entire 35mm film compartment into a camera with a full sized film plane, some compromises were made. The most significant is that both compartments where a roll of film and the take up spool go, are wrapped around towards the front of the camera. This is likely why despite it’s small size, the Mimosa is quite deep front to back.

The top plate has both the rewind and advance knobs which flank the central exposure counter. On the earlier Mimosa I, there is flip up metal viewfinder with an exposure counter in it’s center, but is otherwise the same camera. In front of the film advance knob is a cable threaded shutter release.

The bottom of the camera features only the 3/8″ tripod socket and nothing else.

When it’s time to load film into the camera, you need to open the film compartment, which requires pulling down on a strange looking triangular lever on the camera’s front corner. Like other East German 35mm cameras such as the Altissa Altix, there is no pressure plate on the back, rather it is hinged and attached to the main body, so you must fold it out of the way when installing new film. It is a bit awkward and I found it works best to have the camera upside down on a flat surface while loading film, but otherwise is uneventful.

Like most East German cameras, the Mimosa came with a variety of West German Compur or Prontor copies and simple 3 element lenses. This one has a four speed Velax shutter and an E. Ludwig Meritar 50mm f/2.9 lens. The specs of this lens closely match that of the Schneider Radionar triplet, but I am uncertain if it is a copy of that lens.

Focus is done by rotating the entire front element, and distance markings are in meters. This particular Mimosa was missing it’s infinity stop, so I struggled with accurate focus while shooting it. Most likely this was lost during some previous repair.

The Mimosa II is a neat little camera and has a look unlike any other camera out there, but this is one that even if it was in good working order, I doubt I would use it much. The viewfinder is extremely small and impossible to see the whole frame through while wearing prescription glasses. I don’t understand why the Mimosa II was updated from the original with such a small viewfinder when the trend at the time was making larger viewfinders. The Mimosa is smaller in person than it looks in pictures, but it’s thick depth means it won’t easily fit in a pocket like a scale focus folding camera of the era might. The simple lens and shutter is certainly capable of decent images, but again, nothing special.

My Results

In all previous editions of the Cameras of the Dead series, I share with you cameras that I was unable to use, but this time I have a couple sample pics to share, even if they’re not very good. This Mimosa II actually did kind of work, but because of a missing infinity stop, it was impossible to accurately measure focus. I also suspect the shutter was dragging as every shot I got from a test roll of Arista.EDU 100 film came out over exposed. With these issues and a shooting experience that was less than pleasurable, I didn’t want to take the time to try and fix the camera for another go.

I don’t know that there’s much of a conclusion that can be drawn from these images as they’re out of focus and overexposed. I am certain that when found in good working order, the Mimosa is capable of decent, but probably unremarkable images. Should a Mimosa II be added to your collection? As a display, yeah, they’re pretty neat, but as a user, even if it works, maybe not so much.

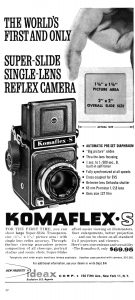

Komaflex-S (1960)

This is a Komaflex-S, a compact Single Lens Reflex camera that shoots 4cm x 4cm images on 127 format roll film. The Komaflex-S was built in Japan by Kowa Optical Works starting in 1960 for export only. The use of the name Komaflex is strange considering Kowa already had a Kowaflex 35mm SLR being sold in the US, so the name change is curious. The camera was an inexpensive but capable design with a fixed Prominar lens that combined with a reflex viewfinder, offered full through the lens composition like any normal SLR. Although generally well built, the camera had an unorthodox film transport which was prone to failure and many of these cameras are found today in inoperable condition.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (Twelve 4cm x 4cm images per roll)

Lens: 65mm f/2.8 Kowa Prominar Coated 4-elements

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Seikosha-SLV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Accessory Shoe with PC Port M and X sync

Weight: 710 grams

Manual: https://www.butkus.org/chinon/komaflex-s/komaflex-s.pdf

My Thoughts

Of the three cameras in this article, the one that I had hoped would work the most was this Komaflex-S. I am a huge fan of Kowa’s 35mm SLRs and in my review of the SET-R, I confidently put it up in terms of usability and image quality to the best of any other camera maker’s models. I also love 127 format TLRs like the Yashica 44 for it’s more compact size, yet large waist level viewfinder and excellent image quality.

I had heard that these Komaflexes aren’t well known for reliability, but I thought maybe I’d get lucky. Nope.

Before I talk about the camera, perhaps I should start with the name. Why is this thing called the Komaflex (with an ‘m’) instead of Kowaflex, like the company’s other Kowaflex cameras? An oft repeated story goes that the camera was designed for export only and upon registering the name “Kowaflex” with the US trademark office, the name was accidentally misspelled as Komaflex, and rather than re-apply to get it corrected, the name stuck. I supposed it could be as simple as that, but it just seems odd that such a simple mistake would make it all the way to production like that. Imagine if Kawasaki or Panasonic had become Kamasaki or Panasomic?

Whatever it should have been called, the Komaflex is shorter but every so slightly wider and deeper than a Yashica 44 which itself is nearly the same size as a Baby Rollei. The camera is still not very pocketable however due to it’s depth and large knob sticking out of the side of the body.

When it was sold, it was billed as the world’s first and only Super-Slide Single Reflex Camera, which was a bit of marketing trickery as other cameras existed prior to it which shot 4cm x 4cm slides, but a combination that they weren’t exported to the United States and the fact that no one used the term “Super Slide” when they were made, is how US importers could get away with such a claim.

The camera sold new in 1960 for $69.95 which when adjusted for inflation, compares to about $615 today, which was a relative bargain compared to larger 6cm x 6cm medium format cameras.

Most Komaflexes came in with an off-blue painted body and gray leatherette, but a few were painted black. Looking down upon the camera from the top, it looks very much like any twin lens reflex with a stylish circular red Kowa logo on top. It seemed that red circle logos were quite popular as Kodak, Bolsey, and Leitz used them as well.

The lid flips up to reveal a pretty normal looking waist level finder, with flip down magnifying glass for precision focus, and an opening on the inside the lid to be used as a sports finder for quick action shots.

The camera’s left side features only the accessory shoe, but the right side is where you’ll find the film advance knob/lever, exposure counter, and a sliding release for the shutter cocking lever. Both sides of the camera have metal loops for attaching a camera strap, which was probably a good idea as the camera’s 710 gram weight would have required some type of stabilization while walking around with it.

Loading film into the camera requires first opening the back, which is done by rotating the large ring around the tripod socket counterclockwise, which pushes a metal finger forward near the bottom of the shutter. The rear of the camera is hinged at the top, which is a bit awkward for loading film as there’s no easy way to set the camera down without the door wanting to keep slamming shut on you.

The film compartment looks like most TLRs in that a new roll of film loads on a spool on the bottom of the camera, then makes a 90 degree turn past the film plane and onto the take up spool.

The process of loading film into the Komaflex-S reveals one of the camera’s biggest weaknesses and perhaps the reason it is so often found in non-working condition. Since mine wasn’t working, I wasn’t unable to do the process myself, but reading the instructions in the user manual suggests quite a few additional steps. It seems you cannot cock the shutter without the exposure counter being at 1, and you need to keep using the sliding lock next to the exposure counter to allow you to cock the shutter. I also found it concerning how often the user manual repeatedly warns you against using too much force while operating the camera which suggests that the designers were aware of the fragile nature of the design.

The Komaflex-S was intended to be a cost effective SLR for those who wanted something larger than 35mm but didn’t want to spend the money on cameras made by Hasselblad or Mamiya. One cost cutting measure was the use of a fixed lens. The fixed 65mm lens was not removable, but when it was new, Kowa made two screw on auxiliary lenses for semi-wide and semi-telephoto shots. Being a through the lens reflex camera meant that when using these accessories, the photographer could see the changes in the viewfinder.

The Seikosha leaf shutter operated like any other leaf shutter with shutter speeds and aperture settings controlled by rings around the lens. There was also a switch for M and X flash sync and a V setting for a self timer.

The Komaflex-S seems like a pretty capable camera that possibly was released at the wrong time as the need for a medium format SLR using 127 film was probably quite small. The price point of under $70 likely meant that some cost cutting measures went into the camera’s design, which caused reliability problems. Kowa would go on to make some other good cameras, just none like this.

I am unsure of how long the camera was in production, but it probably wasn’t very long as the best estimate of how many were built is right around 11,000. Like I said earlier, I had wished this camera would have worked, even a little, but it didn’t, and as a result, here it belongs as a Camera of the Dead.

(Not) My Results

Keeping with the theme in this 8th edition of showing examples from these dead cameras, this time I had to branch out and find what could possibly be the only working Komaflex-S out there. While writing this article, I reached out a large number of collectors I know asking if anyone had a working example and of the people who had one (or many) in their collection, they were all inoperable, except one.

That one camera belongs to Jon Gilchrist of the Packard-Ideal Shutter Company who is also an avid film shooter. Jon had been wanting to take his Komaflex-S out and do a comparison between it and something comparable. He chose a Sawyer’s Mark IV TLR that also used 127 film, and a Yashica-124 TLR that used 120 film to see how a larger negative might compare. For the two 127 cameras, he used slightly expired Kodak Portra 160 and Ilford HP5+ that he cut down to 127 size and in the Yashica-124, regular 120.

Rather than ramble on about what he told me, here is an actual quote describing his take on the camera.

I like the Komaflex-S a lot. The viewfinder is bright and focusing is fairly easy. It feels rough and fragile, but I’ve been advancing the film very carefully and have learned to advance and cock the shutter right before I take a picture so I don’t accidentally hit the shutter button. Looking at the images under magnification, the Komaflex is sharper than the Sawyer’s or the Yashica. I’m going to say that for shooting 127, it’s a toss-up between the Komaflex and the Sawyers for which is my favorite. They’re both ahead of the Yashica 44, but the 44 is much easier to use with 35mm.

Here are some sample images that Jon shot with his camera and gave me permission to publish here. As always, click on each gallery image for the full size version.

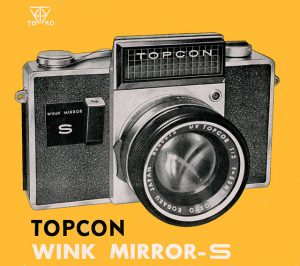

Topcon Wink Mirror S (1963)

This is a Topcon Wink Mirror S, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Tōkyō Kōgaku K.K. starting in 1963. The Wink Mirror S had a central leaf shutter and used interchangeable Topcor UV lenses, which was shared by later cameras like the Auto 100/Uni and Unirex models. There were two other Topcon Wink SLRs, but both had a fixed lens. The name “Wink” was Topcon’s marketing name for an SLR with an Instant Return Mirror which at the time of it’s release, was reserved for professional tier cameras. The Wink Mirror S supported Shutter Priority Auto Exposure via a coupled selenium exposure meter. Although Topcon continued to make UV-mount SLRs until the 1970s, the Wink Mirror S was a short lived model that is hard to find today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 53mm f/2 Tokyo Kogaku UV Topcor coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Topcon UV Bayonet

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Reflex Pentaprism Viewfinder

Shutter: Seikosha-SLV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/Viewfinder Meter Readout

Battery: None

Flash: Accessory Shoe with M and X Sync

Weight: 815 grams (w/ lens), 672 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/topcon_wink_mirror_s.pdf

My Thoughts

I am a big fan of the Topcon RE Super and it’s variants. In my review for that camera, I praised it’s build quality, features, and in body meter. This was a camera that compared favorably to the Nikon F which as we all know was one of the most successful 35mm SLRs of all time.

So when I had a chance to shoot one of Topcon’s consumer models, the Unirex, I was excited. I picked up a nice looking example and took it out shooting, except I didn’t, because it was broke. So I got another, and awww shucks, wouldn’t ya know it? That one was dead too.

Maybe my friend Adam Paul would have better luck with his Unirexes. Nope. How about someone who works with classic cameras all day? I reached out to Johnny Sisson at Chicago’s Central Camera and asked about Topcon’s UV series of cameras and he threw holy water in my face and threatened to burn me on a stake if I ever mentioned that camera again.

As it turns out, Topcon did a pretty good job making professional 35mm SLRs, but not anything else as their leaf shutter cameras like the Uni, Auto 100, and Unirex were pretty terrible.

So when I had a chance to shoot the predecessor to those models, the Topcon Wink Mirror S, I didn’t expect much. Amazingly the camera worked when I first picked it up at a local thrift shop. Thinking I might finally be able to test a Topcon leaf shutter SLR, I quickly loaded film into it, at which time it promptly died.

There’s not a lot of information about these cameras as I believe they were only sold for a year, maybe two, before being replaced by the Uni. Although I do believe the Wink Mirror S was sold in the United States, I was unable to find any advertising mentioning it in any publications. I did however, find a short review of the fixed lens Beseler Topconette, which was the US version of the Wink Mirror E, and it sold in February 1962 for $139.95 suggesting the interchangeable lens Wink Mirror S would have had cost somewhere around $20 – $30 more. My best guess for a retail price for the S would have been $169.95 with steep discounts soon to follow as more advanced models hit the market. If my estimate is correct, that price compares to about $1425 today which is right in line with a mid-level SLR with cutting edge technology.

Unlike German leaf shutter cameras like the Voigtländer Bessamatic and Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex, the Wink Mirror S has a Japanese level of minimalism in it’s design. The top plate of the camera has the rewind knob, meter read out, accessory shoe, and rapid film advance lever. The shutter release is on the front of the camera, but visible from the top. On the bottom is the door release, 1/4″ centrally located tripod socket, and rewind release button.

The Wink Mirror S was Topcon’s first camera to use their new UV lens mount. The letters UV stand for Ultraviolet as the entire series came with an anti-UV coating on the exterior surfaces to block out ultraviolet light for improving contrast. Their professional RE series used the Ihagee Exakta mount, so this was Topcon’s first attempt at their own lens mount.

Swapping lenses isn’t as easy as it is on other bayonet lens mount systems and requires a firm grip with both hands. To swap the lens, you must press and hold a narrow lens locking lever which is near the 5 o’clock position on the side of the shutter. While pressing this lever, rotate the lens clockwise until you can remove it. While rotating the lens both during removal and installation, you can feel resistance from the various shutter cocking and aperture linkages that the lens uses, giving a less than inspiring feel to the whole process.

At the time of it’s release, the Wink Mirror S had two other lenses available for it, a 35mm f/3.5 and a 100mm f/4. Later, as more UV mount cameras were made, other lenses were available that would fit, but longer telephoto lenses would be incompatible with the metering system on the Wink Mirror S meaning these lenses could only be shot with auto exposure off.

The viewfinder is large and bright, with a noticeable circular Fresnel pattern radiating out from the central microprism spot. The entire viewing screen can be used for focus, unlike other German leaf shutter SLRs like the Contaflex in which only the center can be used to see focus.

On the left side is a very large analog metering scale which shows which f/stop will be used when the shutter is fired. At the top and bottom of the scale are two red zones to indicate over and under exposure. The metering system only works with shutter speeds 1/30 to 1/500. Looking at the shutter speed scale, these numbers are in red, whereas 1/15 and under are in white. With the camera in Auto mode, the white speeds are locked out. With the camera not in Auto mode, you can select the white speeds, but the meter will not give a reading.

The overall feel of the Topcon Wink Mirror S is that of a smaller version of the RE Super. Like that model, the body is boxy with a lot of angles to it. The viewfinder is excellent, and Tokyo Kogaku was very good at making lenses. The build quality seems good, but as we would later find out, Topcon’s implementation of the Seikosha leaf shutter would be it’s biggest downfall.

My Results

This Topcon Wink Mirror S is one of many Topcon UV mount cameras that I’ve come across and none have worked correctly. This one came the closest to working in that the shutter would only operate every other wind of the film advance lever, and even then it would only sometimes fire. I figured that maybe if I got some bulk film and loaded a long enough strip of film into it and fired it enough times, I’d get enough images for a usable review.

In late March 2020 at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in my area, I took the camera out with some bulk Kodak TMax 100 in it. I figured that since 1/125 shutter speeds are often a safe bet on cameras with questionable shutters, and I had no idea how accurate the meter would be, I would just use a single shutter speed and meter using Sunny 16.

Frustratingly, when the Topcon Wink Mirror S worked, the images it produced were great. I had always known Tokyo Kogaku could make great lenses as their RE series lenses were some of the best made. I was curious to see what kinds of cost cutting went into the optics of the UV lenses, and I can see the answer is “none”.

These 6 shots are the only six I got on a roll of about 36 exposures. After the 6th shot, the camera completely seized and wouldn’t fire at all, so I removed the film and finished it in something else.

Part of me really wants to get this thing going again, but as with all leaf shutter SLRs, getting them serviced is difficult and expensive, and considering this camera has little to no value, doing so would also be impractical. Still, if you ever were to come across one of these in good working order, shoot it as you’ll likely be very happy with the images it makes.

My Conclusions

As I say in all of these Cameras of the Dead posts, I always have plenty of dead cameras to choose from. Writing as many camera reviews as I do on this site, it is easy for readers to assume that every old camera can still be used, and that’s not true. Sure, many won’t work exactly as they did when they were new, but can often be shot at one or two shutter speeds, but there are a large number that don’t work at all.

Unlike previous articles, I was able to provide you with at least a few images shot through each of the models, despite my declaration that they were dead. I am unsure if this is something I will continue to do, but I thought was especially pertinent in a time when there’s already enough bad news, perhaps the thought that even a “dead” camera can still survive might be a sign of better things to come.

Here’s to hoping that in October I can write a normal article about three more cameras with my usual tongue in cheek humor!

The Komaflex is a really good little camera, and its lens is exceptional. They are not generally hard to get working. I got mine with a stuck shutter, once I had that fixed it never gave me any trouble. It does need film in the camera in order to operate, and its separate film wind and shutter cocking can be a little fussy, but (like other Kowa products) it is better than its reputation suggests.

Richard, thanks for the feedback. Your praise seems to match exacty what Jon said about his. The only bad thing about all these nice thing is that it’s making me want to acquire another! I already flipped the original one I had for this article, and Jon is so happy with his, he’ll likely never let it go, especially not at the prices I would be willing to pay! Maybe someday! 🙂

Mike, your “cameras of the dead” series is a favorite of mine: You come up with equipment that’s rarely found even in semi-functional condition. If you want to spend maybe $150 each, I bet Chris Sherlock could repair both the Wink and the Komaflex, as he specializes in between-the-lens leaf shutter cameras, and will work on stuff other than Retinas (he overhauled two Agfa Karats with Heligon lenses for me, and even did a YouTube series on the CLAs).

I appreciate your feedback and continued support. I don’t often get as much feedback on these Dead articles, but I like doing them as it gives me a chance to cross three models off my list that I otherwise wouldn’t be able to review. In the past, after doing a “dead” review, there have been a few, I was able to later find a better working example and do a full review on. One such model was the Canon AL-1 which turned out to be a really fantastic camera. I also later reviewed the Kodak Retina Reflex IV after doing a dead review of the III. Ironically, I currently have a working III that maybe I could also write something about some day.

Your suggestion of Chris Sherlock is a good one as he probably could do the Topcon and it might be something I’d consider one day as I was REALLY impressed with the image quality and viewfinder of the one I have. The Komaflex however, has already been sold. I included it in a lot of broken cameras I sold off last year. But after reading Jon and Rick Oleson’s (in the comments) praise for this model, perhaps I need to find another!

I’ll definitely do a number 9 this October, and for that, I’ll try to find three equally interesting and uncommon models!

Mike, when I saw the heading and then the Topcon Wink Mirror S I started to pay attention. I acquired one of these last year to add to the “themed” section of my collection. The theme being leaf shutter slrs. Unlike yours, mine is working well mechanically but the meter is dead, so no Auto mode. It came with an abused f2/53mm UV Topcor which I subsequently replaced with a much better unit, and added the 35mm lens as well.

Whilst I still add film cameras to my collection, I’m no longer interested in using film, but I have acquired a UV Topcor to Sony E adaptor from a US company, Rare Adapters, and which trades on ebay with the seller ID ramir73. The adaptor is very well made and links with the aperture control on the lens. Hopefully, I’ll be able to get out and test the lenses soon.

Very cool! I am glad someone besides me even knows what camera that is! As I type this to you, the camera is sitting right in front of me and I can keep winding it and the shutter does fire. I’ve never seen another camera though with this same defect in which the shutter only fires every other time and sometimes not at all. I have probably fired it over 200 times, before during and after that roll I used in the article and it has never once fired correctly two consecutive times. It certainly is weird. Maybe one day I’ll find one like yours, as a working shutter is much more important than a light meter!

A college friend, who happens to be a DIY/handy with tools and electronics sort, has been collecting “for parts/not working” leaf shutter 35mm cameras locally and via eBay. His Topcon Uni seems to be working, but I haven’t heard of him putting film in it. He does have a few “dead” cameras, and has been looking for “mechanically seized” cameras to use the lenses on his Fujifilm X-E3 via various rings and adapters. The search for “old lens Bokeh” has driven this quest, since a Radionar or other “pedestrian triplet” lenses yield interesting out-of-focus highlights even if the corners are mushy or vignetted. One of his “repair nightmares” was the various pulleys and guides found in a not-working-well Canon EF. (It works, but in order “to get this to work, that has to be left undone.”) Focal plane shutters come in all shades of disrepair, from crinkled/shredded/decomposing-rubber coverings to sheared off guides/pins. Some old cameras (Kodak Retina Reflex, especially) are best left in the glass case..

Regarding the Retina Reflex, Chris Sherlock has already been mentioned in this post. He is the guru of these cameras, and a nice fella to boot. He gave me time to dissuade me from even looking at my mint and almost fully working III. If one is really keen to have a fully working Retina Reflex serviced or repaired, Chris Sherlock is the go to man, so to speak.

Mike, Maybe you should rename the “dead” cameras that sort of work and give some pix as “zombies”?

LOL! That’s a great idea! I can’t promise these will all work, but maybe I’ll do that for the next one!

I have enjoyed reading your review of the Topcon Wink S Mirror (what a silly name) as I have just bought one in full working order. It is a solid, heavy and well built camera and everything seems to be just where you would expect to find it, particularly the shutter release button which my finger seems to fall upon naturally, just like the Prakticas. My only complaint about the camera is the Fresnel screen focusing, which I find difficult to use and get the focus just right, but that may be more to do with my 72 year old eyeballs rather than the camera. Another small complaint is the very loud shutter, it would be useless for wild life photography. All in all, it is a camera that deserves to be used. A possible weak point is the Seikosha shutter which, as any Kowa collector knows, either works or it doesn’t, and if it doesn’t they are a nightmare to repair.

I’m really jealous that you found a perfect working one, Richard! I loved the images I got from mine and wish that the camera was more reliable. I do agree with you though as it has one of the loudest shutters of any I’ve heard. Even other leaf shutter SLRs like the Kowa SET-R or Voigtländer Bessamatic aren’t as loud!