You only need to be a camera collector for about five seconds before you discover one of the most frustrating aspects of the hobby. Is it the large number of extinct films that you can no longer get? Is it what do to with all of the “Ever-ready” cases that cameras came in? Is it the unreliability of leaf shutter SLRs?

No, it is the vast number of battery sizes, shapes, voltages, and formulas that have been powering cameras since the dawn of the electronic era.

The number of different mercury, silver-oxide, alkaline, zinc-carbon, nickel cadmium, and lithium batteries that have been powering cameras, flashes, light meters, and motor drives are innumerable and although there were a few that were widely used in a number of cameras, there are also those like Kodak’s ill fated “Type K” battery or the Mallory PX400 used in the Pentax Spotmatic that are impossible to find today.

Batteries came in different voltages with different characteristics. The majority of batteries used from the early 1960s through the late 70s were of the Mercury type which are 1.35v per cell, instead of 1.5v like other technologies. For those of you in the US, the Mercury-Containing and Rechargeable Battery Management Act of 1996 outlawed the use of mercury in any batteries of any kind sold in the United States. Since then, other countries have outlawed the use of Mercury as well, making them nearly impossible to find today.

Some of the more popular sized mercury batteries do have modern equivalents that can be substituted, but not only are they usually a different voltage, their discharge rate is not the same as the originals meaning they behave very differently when they are new compared to when they are partially exhausted. A product called the WeinCell is a replacement battery that comes in many popular sizes that are the correct 1.35v, but they are based off Zinc-Air cells originally designed for use in hearing aids. WeinCells are terrific Mercury replacements, but only for a short time as their shelf life is very short. Zinc-Air batteries react with air and once they are removed from their package, continually discharge, even if the camera is not being used.

If all of this wasn’t enough, furthering adding to the battery mess is that even within the same kind of battery, it’s name changes depending on who makes it. Modern battery makers like Energizer and Duracell do not use the same model numbers as those made in the past. The common type 357/SR44 button cell battery has at one time been called 21 different names. The PX625 battery used in a great number of 60s and 70s SLRs is known by an astounding 33 different names!

Our frustration today with camera batteries is not unique to the 21st century collector as it was a problem even back in the 1970s. This week’s Keppler’s Vault takes a look at an article in the April 1975 issue of Modern Photography when Ed Farber and Kenneth Werner attempted to unscramble the battery mess.

The article covers a wide variety of topics, explaining things I never knew, such as the difference between a PX13 and PX625 battery which otherwise look identical, why hearing aid batteries are not ideal in cameras, and how temperature affects different battery technologies.

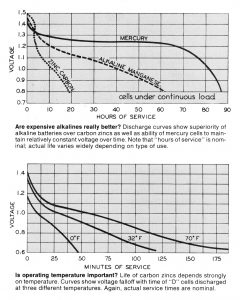

The two charts to the left show the voltage drop off over time of Mercury vs Alkaline batteries. This is why so many cameras that were designed for mercury batteries just don’t work properly with modern equivalents. Even if you were to adjust for the 1.35v to 1.5v difference, whatever adjustment you’d make would only apply at that specific age of the battery and temperature. Shooting the camera outside in the winter or in the heat of the sun or with the battery brand new or 50 percent depleted and you’ll get a different voltage each time.

In 1975 when this article was written, electronic cameras were still pretty basic, but more advanced models like the Canon AE-1 and Konica C35 AF were on the horizon and the article correctly predicts that a change in battery technology was necessary as more advanced cameras were outpacing the technology in existing batteries.

A mention of a breakdown in communication between US battery makers and Japanese camera companies suggests that a new type of battery would soon be needed. One such battery mentioned was the lithium battery which the article correctly predicted would become common in future cameras.

Lithium batteries would start to become common in the mid to late 1980s as new CR2 and 123 batteries would soon become common, although their high prices today sometimes mean collectors such as myself are often swapping batteries from one model to another. I’ve used the same CR2 battery in probably 10 different cameras and it’s always a challenge for me to remember where it is, each time I need it.

Most of the battery challenges faced by camera collectors today are for those found within cameras themselves, but if you collect or shoot with old flashes, there’s a whole other realm of batteries and capacitors to consider.

The biggest difference between flash batteries and those found in cameras, is that they must deliver far more power than the simple 1.35v – 6v cells that cameras required. Voltages in excess of 20 volts with supplemental capacitors were needed to produce a sudden burst of energy to fire a flashbulb. This required a whole separate category of batteries, further adding to the “mess” described in the first article.

This article from the May 1960 issue of Modern Photography is worth checking out for this reason as they cover other types of batteries such as rechargeable nickel cadmium batteries, and “wet cell” lead-acid batteries.

Perhaps my favorite part is at the end where the author looks to the future and predicts the possibility that atomic energy might one day be used to power flashes!

If simply knowing which battery you needed was the only challenge you’d face, what would happen if the kind you needed couldn’t be found in your country?

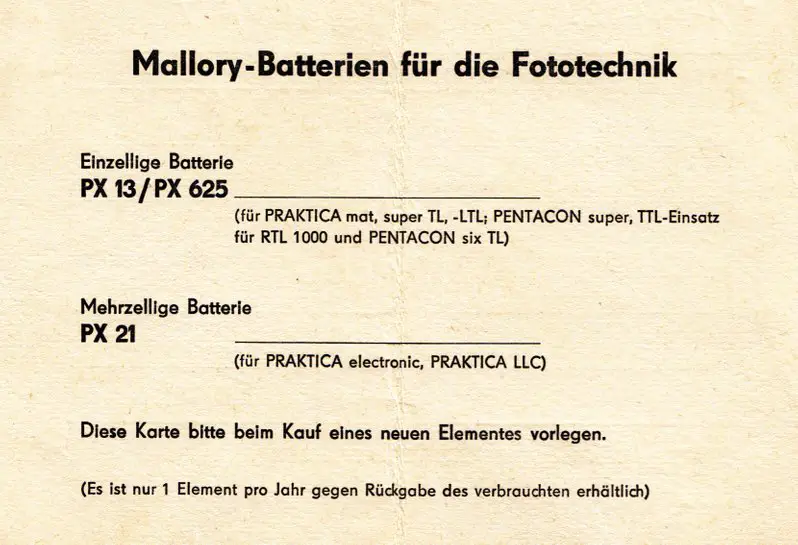

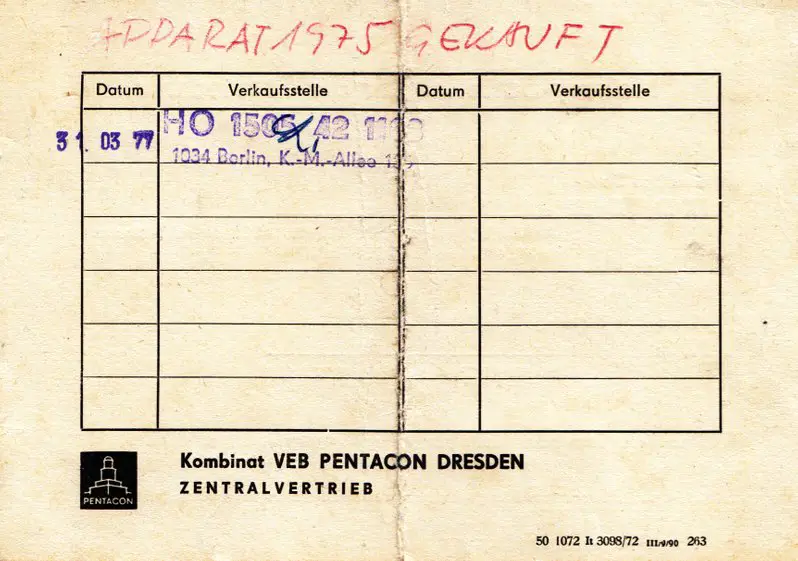

This was a reality camera owners of several different Praktica and Pentacon models faced in East Germany because there were no domestic makers of the Mercury batteries those cameras required. If you owned a camera that needed a PX-13 or PX-625 Mercury battery, you had to put in a request through customs to get one imported, but before you could do that, you needed to prove that you owned a camera that needed one.

Waiting times were often long and the prices were high. This problem continued until the early 1980s when a company called AKAelectric started to produce domestic batteries that could be used in these cameras.

The images below show an example of a card that an owner of one of these cameras would have needed to present in order to import a battery.

For one final bonus, we have this short article from Tony Karp’s 35mm column in the July 1966 issue of Modern Photography where Tony addresses a couple common questions about new batteries.

What I found the most interesting in this are the explanations of what the prefixes PX, HPX, and EPX meant, along with some tips on how you can preserve the life of your batteries (hint: Do not stick them in the fridge!)

This short article gives a rare glimpse into the history of the “battery mess” and that it was just as confusing (maybe even more) back then!

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.

The title of this article suggested the “other” battery mess, the one we collectors often discover when we unpack that incoming Ebay shipment and discover acid corrosion from the battery left in the camera when it went in the closet 30 years ago!

When I saw the Yashica Electro and it’s no-longer-available 6V PX32 battery, my mind went to the PX28, which powered my Bronica ETR-C, AE-1 Program, and Nikkormat EL. Fortunately, the PX28 is still available, though those three battery-dependent cameras “left the building” years ago. I’ve tried to buy cameras that use “commonly available” batteries, but that can change in an instant; got a battery for that mint Pentax Spotmatic? (Ye Olde Nikkormat FTN used the no-longer-available PX-13/PX-625, but that too “exists only in memory.”)

Since the 1980’s onward, I’ve tried to buy non-battery-dependent cameras and exposure meters, but that was an interesting challenge. (Some of the most interesting cameras and photo equipment use such uncommon/exotic/”unobtanium”-type batteries.) At least I don’t have to hook up a Hershey #497 AC battery eliminator to the Braun RL-515 any more;) .

There are several solutions to extinct batteries Example the Electro 35 users have a site where you can purchase a machined cell and insert modern coin batteries to make the voltage and then use the camera. I am sorry I do not have that site info at this time.

Also, When it comes to camera cases for old cameras, “do not store them in plastic bags”. they will sweat and powder over with a coating of mold. I found out the hard way. What I do now is clean them and then brush in a coating of neutral shoe polish or a color if you have one to match the brown or black which are most common. The wax acts as a protection to moisture. Then store them in a vented cardboard box.

I use a bankers box. I will check them on occasions when I will use my vintage cameras with their cases for my photo outings.

Old style “Film” is another issue. 118, 620, 126,127 are long gone from the store shelves. However the 120 and standard 35mm cassettes are available for most of the cameras I will actually use from time to time. I have even found some 136 cassette film format to use in the Canon ELPHz3. which is now an extinct photography platform. Will talk more later, David C

Hey one ye olde factory in russia still produces PX625 type mercury batteries for practica and others (рц-53). I think they do it for the military. You can order from him directly, as organisation in large numbers. Or contact ur friends in russia they can buy and send the butteries to US, and declare they as alcaline.

http://ao-energiya.ru/kontaktyi.html – factory

https://sreda.photo/goods/rz-53 – moscow photo shop who resells, call him for b2c

Ive heard of those Russian mercury batteries before, but thanks for reminding me about them. One of these days, I should do an A/B comparison using them compared to a 1.5v alkaline equivalent.

They are fair 1.35v photo batteries. As declared in magazine article below you should lose only 3.1 % of voltage to the end of the charge. I think the comparison result is clear – mercury vins. The only difficulty is to obtain them. This is not trivial task even here in Russia. As for me i stopped to use light meters in the old cameras to not damage they by 1.5 v alkalines and buy silver oxide elements for the external light meter (although declared that they eat alcalines) to be sure that unstable voltage do not affect measurements.

http://radiowiki.ru/images/thumb/b/b7/%D0%A0%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BE_1966_%D0%B3.%E2%84%9610.djvu/page53-1073px-%D0%A0%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B8%D0%BE_1966%D0%B3._%E2%84%9610.djvu.jpeg