This is a Start B, a Twin Lens Reflex camera produced in Warsaw, Poland by Warsaw Photo-Optical Works or WZFO for short between the years of 1960 and 1967. The Start B was an updated version of the original Start TLR from 1954. WZFO was Poland’s first and only consumer manufacturer of cameras and lenses, of which the Start series was it’s most popular product, staying in production for nearly 30 years. The Start B was a solid, all metal TLR whose features most closely matched that of the German Rolleicord, with a full focusing front lens standard, film advance knob, and an f/3.5 taking lens.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 75mm f/3.5 WZFO Euktar coated 3-elements

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: WZFO Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/10 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe with PC port Flash Sync

Weight: 810 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The WZFO Start B is a nice looking TLR made in a country with a rich history in optics design by a company that long produced quality devices for the Polish army during World War II. The list of features compares favorably to that of other German TLR copies, but despite this example being in rough condition, I feel as though even if I had a perfect example, somehow the camera would still not live up the standards set by other Rollei copies made by other companies. I liked this camera for it’s history, but not much more. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.2 | ||||||

History

Poland is known for many things today, but their optical and camera production isn’t something that most people immediately think of, at least not me. In reality though, Poland’s history as a maker of optical lenses and cameras dates back all the way to the late 19th century when more than a dozen companies existed in Warsaw producing optical products.

Poland is known for many things today, but their optical and camera production isn’t something that most people immediately think of, at least not me. In reality though, Poland’s history as a maker of optical lenses and cameras dates back all the way to the late 19th century when more than a dozen companies existed in Warsaw producing optical products.

The man most commonly referred to as the earliest influence on Poland’s optical industry is Aleksander Ginsberg. Born in 1871 in Sosnowiec, Poland, Ginsberg earned an engineering degree at the Technical College in Berlin-Charlottenburg and later worked both in Paris and in Jena for both Krauss and Carl Zeiss, studying their techniques and gaining skill as a master optical engineer.

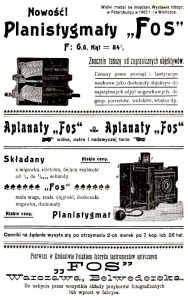

In 1898, Ginsberg returned to Warsaw where he created Pierwsza w Kraju Fabryka Instrumentów Optycznych or FOS for short as Poland’s premiere maker of photographic lenses, binoculars, rifle scopes, and other optical devices. FOS lenses were used by camera makers all over the world including L. Gaumont & Cie, Kruegener, and even Kodak. FOS’s f/6.6 Planistygmat lens was modeled after the Goerz Dagor and was one of the company’s most popular lenses of the early 20th century.

The success of FOS was short lived, as a combination of factors including the death of Aleksander Ginsberg in 1911 and continued political turmoil which would lead to Poland’s independence in 1918 caused the control of FOS to disintegrate, eventually disappearing altogether.

The next major step in Poland’s optical history occurred in 1921 when a new company called Factory of Optical and Precision Devices H. Kolberg & Co, or Kolberg for short, was established by a Polish optical engineer named Karol Hercyk-Pałubiński, a Russian financier named Henryk Kolberg, and two more businessmen named George Coro and Kazimierz Mieszczański.

Progress in making the new company was slow, as machinery and supplies necessary to create new optical products were in short supply. Kolberg also needed to build a new factory and train it’s workers from scratch, which required a bit of time. The first products made by Kolberg were simple devices such as loupes, magnifying glasses, and later, binoculars.

By 1927, almost all of Kolberg’s production was to supply the Polish military with binoculars and other scopes. This led to the company expanding into a new 2500 square meter factory and in 1932 an entirely new 1900 square meters factory was built. Between the two factories, Kolberg was able to expand their product offerings to microscopes, rangefinders, and sights for anti-aircraft cannons.

Around 1930, likely due to financial reasons, Heryk Kolberg parted ways with the company, selling his interests to the French company OPL. The remaining interests of his former company were reorganized, forming a new entity named Polish Optical Industries, or PZO for short. A short time after leaving his original company, Kolberg would create a second H. Kolberg & Co., to compete with PZO, and in 1936, now managed by his son Stefan, Kolberg & Company won over a military contract to supply the Polish military with binoculars, a contract that proved to be the downfall of the company as they were unable to meed the demands, which ironically was picked up by PZO.

During World War II, both Kolberg and PZO produced binoculars and other products for the German occupation, but in 1944, the resources and factories of both companies were merged into one, managed by PZO in Warsaw.

Between July and August 1944, with the Soviet army crossing into Poland, to avoid the PZO factory and equipment in Warsaw falling into enemy hands, Germany ordered the dismantling and relocation of the PZO factory’s machinery and spare parts. The German army began loading materials onto trucks which were bound to German occupied locations in Czechoslovakia.

Led by a resistance movement of Polish workers, an engineer named Stanisław Cegliński led a rebellion in an attempt to sabotage the efforts of the German military’s dismantling of PZO. Production tools and raw materials were saved by Polish workers and hid elsewhere in Warsaw, entrances to factories were barricaded to prevent the removal of equipment, German explosives were sabotaged, and in some cases, German solders were even offered bribes to prevent the destruction of the PZO factory.

Although effective at first, Cegliński’s efforts only temporarily delayed the Germans as by September, the German military returned in greater numbers to completely demolish the PZO factories and whatever equipment remained. Stanisław Cegliński was captured and sent away to Czechoslovakia to work in an optical factory there.

Now occupied by Soviet forces, with enthusiastic support from the remaining workers in Warsaw, work began in October 1944 to rebuild PZO with what equipment was saved. Loans and food rations were established to aide the 80 or so workers trying to rebuild the factory. In December, a cache of sample templates, micrometers, calipers, and many other tools were found buried in rubble which greatly aided restoration of the machinery.

Production of simple optical lenses for eyeglasses and binoculars began in early 1945 before the factory even had electricity. By June 1945, now fully electrified, production at PZO was well under way. With the war now over, Stanisław Cegliński returned to Warsaw, and was able to pinpoint the locations of the relocated machinery in Czechoslovakia and began the negotiation with the new Czech government to bring it back to Poland.

Demand for optical equipment like microscopes and other lenses was very high for medicinal and scientific use and PZO’s products were sold as quickly as they could be built. Near the end of 1945, Stanisław Cegliński was appointed the director of PZO and under his guidance, PZO secured loans from the government, allowing them to begin work on a new 3100 square meter facility in nearby Łódź.

In April 1948, PZO was fully nationalized and production continued to grow. In the next decade, PZO was the largest European producer of optical equipment outside of Germany. Their microscopes and binoculars were exported all over the world and remained a popular choice for hospitals and universities.

In 1951, under the direction of Polish Prime Minister, Bolesław Bierut, the creation of a new company called Warsaw Cinetechnical Works was ordered to begin production of photographic cinema equipment. First located in partially destroyed buildings still left standing after the war, management of the new company was given to Poland’s department of Heavy Industry, and the name of the company was changed to Warsaw Photo-Optical Works, or WZFO for short.

Production of cameras in Poland was quite difficult as there wasn’t anyone there with a great deal of experience in producing them. The little knowledge that long time workers at PZO had all came from their knowledge of cameras from the 1920s and 30s. For their first camera, a twin lens reflex design, heavily based on German cameras produced by Franke & Heidecke was chosen, and the first cameras were cleverly given the name, “Start”.

Although strongly resembling the Rolleicord, the Start TLR was an entirely new camera. The shutter was designed by Janusz Jirowiec and the first lenses were produced by PZO, under license to WZFO.

Shortly after the release of the Start, WZFO produced a line of Krokus enlargers and a couple of different compact 35mm cameras like the Alfa and Fenix. WZFO’s products were enthusiastically received by the Polish people along with those from other countries as German built cameras were still extremely expensive and difficult to acquire. Although by this time, the Japanese camera industry was well on it’s way to later dominance, affordable Japanese cameras were not yet imported to Poland, so almost no one knew of their existence.

The Start sold well, and in 1958, work began on two replacement models, a higher end Start II with automatic film advance coupling, double image prevention, and a Rolleiflex style film advance lever, but also a less expensive version called the Start B. Production difficulties plagued the Start II, but the simpler design and cheaper cost of the Start B allowed it to be very successful both domestically and elsewhere. It was claimed that up to 40% of Start production was exported, but it is not clear to where.

While researching this article, I attempted to find advertising or marketing material for the Start camera and was unable to find anything. Knowing that the Start TLRs were sold as lower cost alternatives to German Rolleis, I’ll make a wild guess that the retail price of a Start B was probably 40-50% cheaper than a Rolleicord. In a 1960 catalog for Olden Camera, a Rolleicord Va sold for $114, which if my theory is correct, would have put a Start B somewhere between $60 – $70.

In the mid 1960s, WZFO began to suffer from financial difficulties, and the company’s ownership changed hands a number of times. It’s product lines were thinned, eliminating slower selling products. In 1966, the Start B was given a face lift and used more modern materials, and was not called the Start 66. Finally, in 1968, both WZFO and PZO were merged together as one single company. A final version of the Start, called the 66 S remained in production until 1982 at which time, the company seemed to disappear.

Today, there’s not a huge amount of demand for Polish cameras. With the exception of the Start, most cameras built in Poland were simple devices that don’t have a large following in collector groups.

On paper, the Start TLR might not be much different from the countless numbers of other Rolleiflex and -cord copies, but for those like myself who appreciate the historical side of collecting, companies like H. Kolberg, PZO, and WZFO have fascinating stories to tell, making cameras like the Start TLR worthy of addition to any collection.

My Thoughts

My mom’s whole side of her family is Polish, her mom being first generation from Poland and as a small child, I remember being around my grandma and her Busia speaking some strange language I didn’t understand. In the years since, I never learned to speak Polish, but I remember eating all sorts of pierogi and golumpki.

As my journey into collecting cameras progressed, I found it extremely interesting to see models made in countries like Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, and others that weren’t the same old German and Japanese brands. With brands like Meopta, Royer, and Bencini I was intrigued. I had known of Polish made cameras, but none ever came my way until one day I was marveling about how many cameras were called the Start. There’s the Pouva Start, KMZ Start, and the Ikko Sha Start 35 K-II, but then when I found out there was a WZFO Start made in Poland, I had to step up my search.

In late 2019, this rough looking example came my way and at first, was completely inoperable. The viewfinder hood was damaged and very difficult to get open, the shutter wouldn’t fire, the lenses were cloudy, and the body was in overall very poor condition.

After sitting on my shelf for a couple months, I finally got around to cleaning the lenses, flushing the shutter, wiping down the body, and hammering the viewfinder hood into a semi-operational state. Satisfied that the camera appeared to be working, I took it out shooting.

Despite being entirely built in Poland, the Start B was heavily influenced by the Franke & Heidecke Rolleicord which means most of the controls are in the most familiar places. Starting with the camera’s left side you’ll find the focus knob which moves the entire front lens standard fore and aft from 1 meter to infinity. There is a very simple depth of field scale above the knob, only showing marks for f/4, f/8, and f/16. Above and below the focus knob are two pull out knobs which are used for loading film to release both spools.

The camera’s right side has only the film advance knob and an accessory shoe. This location of the accessory shoe on the bottom of the right side is unusual as anything mounted there would likely get in the way of the photographer’s right hand as they were trying to reach for the shutter release.

While taking beauty pics of the Start, I forgot to take a pic of the camera’s back, but all that’s there is a red window with a sliding door to protect it from light. The Start does not have automatic film advance, so you must pay attention to the printed exposure numbers on the film’s backing paper when advancing the camera.

Opening up the camera is very un-Rollei-like with an unlabeled small wheel on the base of the camera in front of the raised tripod socket. When I first got the camera, it took me a good 10 minutes of fiddling to get the thing open. As it turns out, this wheel has a simple latch that hooks onto the front edge of the camera when turned fully clockwise. To release it, simply rotate this wheel counterclockwise. You don’t even need to go all the way as the latch is unhooked with a quarter turn, but the door is on so tight, that it does not open easily. As I’ve reference multiple times in this article how this Start came to me in poor condition, I’ll concede that mine is just stiff, and that perhaps others aren’t as difficult, but if yours is the same way, just rotate this wheel counter clockwise and pull back on the door…HARD!

Thankfully once the door is open, loading film into the camera is very predictable. Install a fresh roll of film on the bottom and pull the paper leader over the rollers, and onto an empty take up spool near the top. You’ll notice in the middle of the film gate is a triangle which would normally appear on a TLR with automatic film transport that allows you to line up with the starting line on a new roll of film, but the Start lacks this feature, so whether you line up the start line on the backing paper of your film with this triangle or not, you still need to use the red window for all exposures. At the same time this Start B was being made, WZFO also made a Start II which did have automatic film transport, and it’s possible they used the same body casting, which could explain why this triangle is there, but it serves no purpose on this camera.

The viewfinder of the Start works like any other TLR. The hood pops up to review a ground glass focusing screen that looks through the top viewing lens. With an f/stop of 3.5, brightness is acceptable, not the best I’ve seen, but not the worst. There is a folding magnifying glass that is hinged on the front of the lid for precision work. The middle section of the lid can be folded down over the ground glass to be used as a sports finder through a small square hole on the back of the viewfinder hood.

Up front, the unnamed leaf shutter has a rim set dial with speeds from 1/10 to 1/250 plus Bulb, and apertures along the bottom edge, like you’d expect to see on a Prontor or some East German Cludor copy. The most unfortunate part of the Start’s controls is the shutter release which is a button connected to a long metal shaft. While the location of the shutter release is fine, on this example, it was very stiff. Again, this could be a conditional issue with this camera, but after taking a good look at it, I don’t see any obvious damage, which suggests that this is just how it was designed.

The Start B is a camera that on paper, has everything you need to have a capable Twin Lens Reflex camera. It’s design is inspired by quality German TLRs, it has a shutter that appears to be as modern as others out there, twin lenses with nice color coating, and a reflex viewfinder with sports finder and magnifying glass just like all the other popular cameras did, yet in use, there seems to be something missing from the camera.

As I’ve mentioned a number of times, this camera was in poor condition when I got it, so things like a rough shutter release, peeling body covering, and a shutter with questionable slow speeds aren’t something that would be fair to critique the camera on, but somehow, while handling the Start B, I get the feeling that even if I had a mint condition camera that was in perfect working order, it would somehow not perform as well as other similarly spec’d models.

I guess the only way to know for sure is to load in some film and shoot with it, so keep on reading!

My Results

For the first roll of film through the WZFO Start, I chose a roll of Kodak Portra 160NC that had expired in 2002. I’ve shot this film before and expected the colors to come out slightly muted, but still good enough to work within the late winter/early spring color palettes around my house.

Although not well known for their cameras, Poland’s optics industry had a long history of making lenses, so despite the rough condition of this camera, I had hoped the images I would get from it would be pretty good, and well, I dunno, just look at them.

Center sharpness is pretty decent, but each of the 12 I got from my first roll had severe softness near the edges. Vignetting was kept to a minimum, but looking near the edges, you would be forgiven if you thought this camera had a doublet or even a meniscus lens. Color saturation was muted and there was some horizontal banding in some of the images due to the age of the expired film, so I obviously can’t blame the camera for that, but I was pretty surprised to see the overall poor quality of the images.

It’s entirely possible given the rough condition of this camera that there is something wrong with the lens elements. Maybe one is out of position, but I don’t think so. Although I didn’t completely disassemble the camera, I don’t see any evidence of a flipped or missing lens elements. The fact that the center of the images look fine suggest this is just how the lens always performed. Now of course, if this kind of blurred edges is what you’re looking for, then maybe the WZFO Start is the camera for you as some people like intentionally distressed images like these.

Acknowledging the very likely possibility that I would have gotten better results from a camera in better condition, there are some other issues I have with the camera’s ergonomics that are just strange. For starters, the design of the shutter release is terrible. While a body mounted button like that on a Rollei or many Japanese copies would have been best, even a simple lever like that on a Compur shutter would have been better than what’s included here. Protruding out of the camera like this just invites it to get banged around and snag on things, which is likely why it was so stiff on this example. I also really didn’t care for the film compartment latch. Rotating the knob to open the film compartment is very hard to do, likely as a result of it’s design that is easily damaged. There is also no arrow or any indication of what direction to rotate it.

The inclusion of a half-hearted depth of field scale and useless film loading arrow in the film compartment certainly don’t hurt anything, but also suggest a camera whose designers did not pay much attention to the small stuff. Finally, although I didn’t have any use for the accessory shoe, the location on the camera’s right side where the photographer’s hand would reach for the shutter release was poorly thought out. Mount any kind of flash bracket or accessory meter to the shoe, and you will have to reach around it to access the shutter release.

Not everything was bad with the Start though. With the exception of the shutter release, the rest of my complaints are just nit picks. The viewfinder wasn’t very bright, but outdoors it wasn’t that bad. Certainly no worse than other early TLRs like the Rolleiflex Old Standard. Had I wanted to improve the usability of the Start’s viewfinder, an aftermarket Fresnel lens would have gone a long way but the camera’s other issues would make that a poor use of a good viewing screen.

By far, the coolest thing about this camera is it’s history. If you just want to use a mid century TLR, there are far better options, but if you like a good story, then you may want to consider adding one to your collection. I am happy to own this camera and I doubt I’ll ever get rid of it, but I also doubt I’ll ever shoot it again.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Start_(TLR)

Nice review Mike. Just one comment: “Pierwsza w Kraju” just means “first in the country” and is not part of the name.

Hello,

it is possible that bad sharpness along picture is caused that film is not firmly pressed (undulated, wavy) by poor back side pressure plate (weary). I experienced this case with my Zeiss Ikonta, when I was after first film very disappointed. But by carefully measurement I discovered this type of failure and putting extra springs I have now excellent pictures. Good luck. Jaroslav

You could be right. This is something I will have to investigate the next time I take the camera out. I definitely liked the Start, and was surprised at how soft the edges were!

Hi Mike! I’m surprised to see a “Start B” review amongst all the other cameras. On the other hand there is so many of them, it shouldn’t probably surprise me. Anyway – Start B was my first venture into medium photography. I couldn’t afford anything better at that time, and so I’ve ended with this consumer grade camera. I’m from Poland, so there was a layer of historical context as well, as you’ve mentioned. I didn’t shoot that much with this camera in the end, but mine results clearly show that there’s something wrong with the lens in your copy. Photographs I got were sharp, I didn’t notice any degradation in the corners. I was very impressed at that time, I still am to be honest. The shutter button operates quite smoothly as well, times seem to be accurate. The thing that put me off the most was the viewfinder brightness. I found it difficult to use indoors and in the dim light. The camera sat dormant for few years because of that reason. I’ve recently ordered and installed a much brighter Fresnel focusing screen (it has been more expensive than the whole camera itself), I might do the same with the mirror, as the old one has deteriorated badly.

Not sure why I’m doing that with a camera that I don’t intend to use that much. I guess it’s a right thing to do with a piece of historical equipment, even if cheap and obscure.

Hi Mariusz! I agree the images I got from mine aren’t indicative of what the camera should be able to do. I did note that the camera was in poor condition when I got it. Although I do try to be as thorough as possible and wouldn’t normally review a poor condition of a camera, these are so uncommon here in the US that I didn’t think it was likely I’d ever see one again, so I went for it anyway and those were the best shots I could get. Thanks for the feedback, it was cool to hear your story about how you got your first one!