I was born in 1978, which means I was six years old when Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom came out. I honestly can’t remember if I saw this movie in the theater, but by the time it would have come out on cable or home video, it was the perfect action adventure movie for a seven or eight year old version of me.

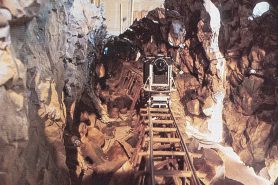

This movie had everything, plane crashes, gun fights, whips, monkey brains, a chamber full of bugs, and a hero and his sidekick beating up on some ruthless bad guys. But of everything that’s cool about this movie, the coolest scene from the coolest movie of my childhood, is without a doubt the mine cart chase near the end of the movie.

Rather than describe it for you, here is a clip of the entire scene that even if you’ve seen it a hundred times, is worth watching again.

In what is perhaps a fitting twist, years later as my love for film photography grew, I learned that a large part of the filming of this sequence was done on one of my favorite cameras, the Nikon F3.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings you a short article from the August 1985 issue of Popular Photography in which Fred Rosen pulls back the curtain to reveal how the Nikon F3 came to be the chosen camera for this scene. The article is a short read, but explains how building a life size replica of what needed to be filmed was prohibitively expensive, so a smaller scale model was required. Yet, building a small scale model required a small camera, and there was no camera of sufficient cinematic quality available that could handle the job, so Dennis Muren of Industrial Light and Magic looked to cameras that already existed and ended up with the Nikon F3.

Of course, making this scene a reality was a bit more complicated than simply attaching an off the shelf 35mm SLR to a scale model mine cart and shooting away, as the camera had to have a modified motor drive, a completely unique bulk film back that held up to 50 feet of film, and an entire miniature set built to the scale of the camera.

The size of the Nikon F3 is what dictated the size of the model because the scale of the images the camera would shoot needed to match the scale of what was captured because if the scale was off, the resulting stop-motion images could not seamlessly be edited in with footage shot with real actors on a life size sound stage.

When shooting stop motion images intended to be inserted into a motion picture, you need 24 exposures for one second of screen time, so unless Muren wanted to keep changing rolls of film every 24 or 36 exposures, a bulk film back was needed. An off the shelf Nikon F3 back wouldn’t work however as it caused the film to slip, so a custom one needed to be made.

When shooting stop motion images intended to be inserted into a motion picture, you need 24 exposures for one second of screen time, so unless Muren wanted to keep changing rolls of film every 24 or 36 exposures, a bulk film back was needed. An off the shelf Nikon F3 back wouldn’t work however as it caused the film to slip, so a custom one needed to be made.

As the scene was shot, a single image would be exposed, and then the cart would be moved an appropriate amount to recreate what a full size camera would capture on a real mine cart speeding along the track. This would be repeated for the duration of the whole shot, which in real time was only 4-5 seconds each.

The finished movie contains about 50 of these shots done with the Nikon adding up to about 5 minutes of screen time. The entire project took four months to shoot which sounds like a long amount of time, but would have taken considerably longer had Muren and his team not found a way to automate many of the tasks with the Nikon.

As a small bonus, I found this VHS quality documentary showing behind the scenes footage and I’ve included a link to the exact point where the Nikon F3 is discussed and shown in greater detail than the Popular Photography article shows.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.

Sometimes removing the mystery of how something is done can remove the magic of it all. I felt better when I was in complete ignorance!

I can understand that! In that case though, you’ll definitely want to avoid next week’s post, “Where did that rabbit come from?” 🙂

Many moons ago, American Cinematographer magazine did a similar deep dive into the making of the “slit scan” light show scene near the end of Kubrick’s “2001”. These stories fascinate and challenge me to be a tad more creative with my own shooting.