This is a KMZ Ajax-12, a subminiature camera that shoots images 18mm tall by 24mm wide on bulk loaded unperforated 21mm film. The Ajax-12 was built specifically for the Soviet Union’s intelligence agencies and is commonly referred to by it’s KGB name, which is F-21. It uses a spring wound clockwork mechanism to tension the shutter and advance the film after each exposure. Although the camera can be used “naked” as seen in the image below, it was commonly used for covert photography concealed behind or inside of something else. The Ajax-12 has the distinction of being one of the longest produced single model cameras in the world, with a production run from 1952 to about 1995.

Film Type: 21mm Bulk Film (~Fifteen 18mm x 24mm exposures per roll)

Lens: 28mm f/2.8 OF-28T coated 3-elements

Focus: 5 meters fixed

Viewfinder: None

Shutter: Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 1/10 – 1/100

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 175 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The KMZ Ajax-12 is one of the coolest and most unique cameras I’ve ever held. It’s a pretty basic camera, but when used to it’s strengths, is capable of pretty good images. The single biggest challenge to using the camera is cutting and loading 21mm unperforated film, which I found to be a challenge, but once you have one loaded, you can feel like a Cold War era spy, taking discreet photos of people around your city! Very cool! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for extreme uniqueness, it’s a freakin’ spy camera! | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.1 | ||||||

History

Aaah, the US and Soviet Cold War… It is strange today to think back to a stressful time when the number 1 and number 2 world powers were locked in a “whose dick is bigger” forty year stalemate that upon it’s conclusion, not much had happened.

The Cold War might have had the potential for World War III, but thankfully that never happened. Instead, we had a really intense space race that forced American and Soviet scientists, engineers, and other researchers to come up with some pretty cool new technologies like freeze dried food, memory foam, and LEDs.

Perhaps less significant, but entertaining nonetheless was Hollywood, who gave us some great movies like WarGames, Rocky IV, and Red Dawn. A common theme in American movies that touched upon the Cold War was about Soviet spies. These were KBG operatives who would infiltrate the American way of life, trying to steal our secrets and bring them back to their leaders. In those movies, Soviet spies always had spy cameras. Little tiny devices, usually in the shape of Minox 16mm cameras that could seemingly take photos of the highest detail in the worst of lighting that could always be “enhanced” later.

The reality was that although spy cameras did exist, they usually didn’t look like the ones I saw on TV growing up, and they were often used for much more mundane purposes, rather than spying on American families.

As I started collecting cameras and learned more about the Soviet camera industry, I became impressed with the quality of Zorki and FED rangefinders, SLRs like the KMZ Start and Kiev 15, and the inexpensive plastic point and shoot cameras like the Smena-8 and Agat 18K. So when I had the opportunity to shoot an actual KBG spy camera, I jumped at it.

To understand the Ajax-12, you must first understand a bit about the history of Soviet “covert photography” as it was called back then. I am not a historian, nor do I claim to be an expert on Soviet era espionage, so a large part of the next section of this review comes from an excellent article on photohistory.ru, which credits the information to the Keith Melton Spy Museum, Boca Raton, Florida and Mr. Detlev Vreisleben’s personal archive. I’ve done my best not to plagiarize any of the original article, but rather to take bits and pieces in an effort to put together a cohesive history of the Ajax-12.

Recommended Reading: If you have even a passing interest in Soviet clandestine photography during the Cold War, I strongly urge you to check out the book, “The Secret History of KGB Spy Cameras: 1945–1995” by H. Keith Melton and Lt. Col. Vladimir Alekseenko. This book contains 192 pages filled with some of the most well researched information about cameras used by Soviet Intelligence offices during the Cold War. There are a ton of highly detailed photos never before seen anywhere else, and is absolutely worth the price it sells for.

Ever since the October Revolution which birthed the Soviet Union in 1917, there has been a long tradition of secret police organizations who served a variety of functions from state security, government intelligence, to flat out espionage. Starting with the Vecheka from 1917 to 1922, the Soviet secret police evolved many times, changing names often from the NKVD “People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs”, OGPU “Joint State Political Directorate”, MGB “Ministry of State Security”, and finally the KGB “Committee for State Security”.

Prior to, and during World War II, none of these organizations had what anyone would call a specialized spy camera. Whenever discreet photography was required, agents often used modified versions of regular cameras such as the FED rangefinder. These early spy cameras would usually have their manual film advance mechanisms replaced with clockwork wind up motors which would allow the camera to be triggered remotely, like from within a coat pocket without having to keep winding the camera on to the next exposure. They also would feature wide angle lenses to both maximize the area which could be captured but also to benefit from the huge depth of field, eliminating the need to focus on your subject.

The relative large size of both the rangefinder and enclosures they came in meant that concealing them was difficult. Some offices began importing German Robot cameras which were not only smaller, but also met all the requirements of a spy camera having a clockwork film advance and availability of wide angle lenses as standard. Robot cameras were expensive however, and repairing them was difficult, so it was demanded that the Soviet optics industry come up with their own solution that would be discreet, automatic, easy to use, and inexpensive.

As a result, in 1945 by order of the Operational and Technical Directorate of the USSR, a new facility was created to first study and then build a sufficient camera for use by the Soviet Union’s various state security offices.

The first product created by this new facility was called the Ajax-8. This new camera was in the shape of a small rectangle, no wider than the palm of your hand that operated with a side mounted plunger that tensioned the shutter and advanced the film before each exposure.

To accommodate the compact size, 21mm wide film was chosen as it was easy to cut down from widely available 35mm stock. The smaller images were 18mm x 24mm, exactly half that of the FED rangefinders previously used. This reduction in exposure size had a negative effect on image quality, as did the rudimentary 28mm f/4.5 A-1 lens, which along with the slow and noisy operation of the camera generated many complaints by security officers. A lens upgrade to a 28mm f/2 A-4 lens improved image quality, but the camera was still too slow and loud to be effective.

In 1949, a new and vastly improved model called the Ajax-9 entered service that had a similar size body, but instead of a side mounted plunger that was only good for a single exposure, the new camera had a clockwork knob, similar to that from the German Robot camera that with a single wind, was good for up to 15 exposures without having to wind the camera again.

The improved A-4 lens was retained on the new model, and improvements to the reliability of the shutter meant for more accurate exposures, but also reduced the noise from the earlier camera. The Ajax-9 still used the same 21mm film, but larger cassettes meant that a length of up to 600mm could be loaded, allowing for 15 exposures per roll.

A year later, the camera was updated once again, this time as the Ajax-10. No new features were added to the camera, but the overall build quality and ergonomics were improved, including better machining to the interior parts which reduced scratches on the film as it passed through the film plane.

In 1951, an all new second generation Ajax camera appeared as the Ajax-11. The camera had a new body and completely overhauled shutter and spring wind mechanism that was significantly quieter and more stable. A more convenient shutter speed lever was added to choose between multiple shutter speeds, and for the first time on a Ajax camera, an exposure counter was present.

The Ajax-11 passed numerous field tests and received positive feedback from the operational staff of the MGB. It is not clear whether the Ajax-11 existed as a prototype or as a widely available model, but by 1952 it was decided to transfer the construction of this new camera to a special workshop within Krasnogorskiy Mechanicheskiy Zavod near Moscow. There, with the experience of the KMZ staff and more advanced machinery, the camera could be more quickly and cheaply produced.

By 1952, the Ajax-12 went into production at KMZ, the first in the series built there. The Ajax-12 was mostly unchanged from the Ajax-11 with the only changes being an easier way to reset the exposure counter back to 0, and a serial numbering system engraved on the front plate. No identifying marks of any kind were put on the cameras to indicate their maker or any specs about the camera. Internally, the Ajax-12 was identified as F-21, which was it’s Ministry of State Security identification code (the KGB was not formally created until 1954, two years after the Ajax-12 went into production).

With each Ajax-12 built, it included a remote shutter release, two pairs of four cassettes in a protective case, a 21mm film cutter, and a specially designed plastic bowl for developing the film.

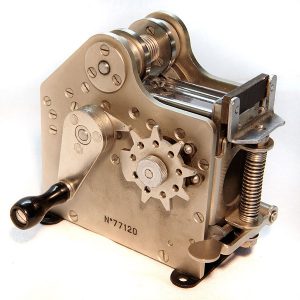

The film cutter was an elaborate device which allowed easy operation of cutting 600mm lengths of bulk 35mm film down to 21mm. The cutter had to be used in complete darkness, so as not to expose the film.

It’s use required installing regular type 135 film into the receiving slot of the cutter, and by rotating a handle, was fed through the cutting elements and into an empty cassette. With the help of a toothed drum, the required number of frames was counted, after which the rotation of the handle was automatically stopped once the correct 600mm length was obtained.

Once the cutter reached it’s limit, a lever on the side was pressed, slicing the film from the rest of the bulk roll. The cassette was now loaded, and the remaining edges of the film could be thrown away. With practice, this process could be completed quickly, allowing for easy reloading of the camera.

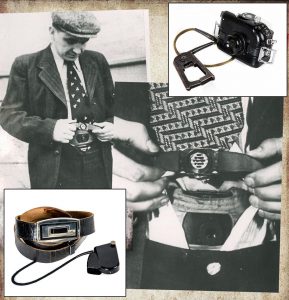

In the field, the Ajax-12 was concealed in the agent’s clothing, often behind a belt buckle or a fake button on a coat. Other creative uses of the camera were used such as behind a ladies brooch or within fixed objects not related to clothing.

Getting the camera ready for use was an involved process that photohistory.ru describes below: (quote edited slightly to improve English translation)

The “Belt” covers were put on in the following way: first, the employee put on a belt-bandage on his naked body and tightly fastened the buckles on the back. Then the Ajax was installed in the belt pockets so that it’s lens protruded outward. Through a hole in the bandage, a photographic cable was pulled out, which was screwed onto the shutter release button of the camera. Lens holes were cut in the shirt and trousers. Having put on trousers, the employee put a buckle on the lens, passing the halves of the belt through the belt loops of the trousers and fastening them at the back or side. The shutter release cable was brought out into a trouser pocket.

The shirt and trousers of the employee had to look neat, not to look sloppy or have wrinkles. Nothing should have hindered the employee’s movements. As a rule, the “Belt” cover was used by an employee who was not overweight or had a large belly. The necktie was often tied so that its lower end slightly covered the buckle. When photographing, the employee leaned back a little, the tie was slightly raised and the photograph was taken.

In order to be given a camera, agents received specialized training in it’s use. Since the camera is triggered remotely via a shutter release cable and there’s no way to aim it at your subject, the user had to have good instincts for positioning his body so as not to cut off the intended subject of the photograph. Clandestine photography is often taken in a fleeting moment with little to no advance notice, so it was critical that the agent knew how to properly use the camera.

Although intended to be used in situations with good lighting, highly experienced agents could take advantage of the Ajax’s Bulb mode, allowing for long exposures in poor lighting of subways, interior locations, or at night. The agents who were able to utilize the Ajax effectively in the most difficult shooting situations were often praised by Soviet leadership and likely given promotions and better accommodations as a reward.

The Ajax-12 was extremely successful with widespread use by the KGB and other state agencies. Examples were used outside of the USSR and even some by other Warsaw Pact countries and those friendly to the USSR.

Over the next couple of decades, the Ajax-12 continued production, largely unchanged. In 1975, KMZ released an updated camera, with the name “Nylon” that used the same basic body, but included an electronic shutter with automatic exposure. To power the camera, an external rechargeable battery pack was needed, reducing some of the portability of the camera. In the field, the Nylon camera proved to be unreliable, and it required re-training for it’s use to accommodate the exposure meter. As a result, the camera was not successful and quickly abandoned.

In 1989, a commercial version of the Ajax-12 was created as the Zenit MF-1. The camera was largely unchanged, apart from being the only version of the Ajax-12 that was identified with a name or the KMZ maker’s mark. The camera stayed in production until the mid 1990s, with the last examples having serial numbers suggesting a 1996 manufacture date. Unsold new stock still shows on Lomography’s website for $800, although as I write this, the website says they are on backorder.

The Ajax-12 was produced from 1952 through the mid 1990s making it one of the longest lived of any single Soviet camera model. It is impossible to know exactly how many cameras were built, but with such a long production run, it stands to reason the number is quite high.

Today, the Ajax-12 is a highly sought after camera by a large number of interest groups. It has interest by camera collectors, Soviet collectors, and those interested in Cold War espionage. The Ajax-12 is a relic of a fascinating part of American, Soviet, and world history that appeals to a great number of people. If you have an opportunity to pick one up, expect to pay quite a lot of money for it as despite their long production run, don’t show up all that often for sale, and when they do, prices are often very high.

My Thoughts

It’s not every day that one of the world’s biggest Soviet camera collectors gives you an opportunity to shoot with one of the most famous Soviet spy cameras. That day happened to me sometime last year when I went to visit Vladislav Kern’s USSRphoto museum. Vlad demonstrated how the Ajax-12 was enclosed behind a button in a coat and shot via a cable release by KGB spies.

When asked if I wanted to try it, I said heck yeah! I knew the camera used special 21mm film, and I thought that it shouldn’t be too hard to come across some, but sadly, I was wrong. While there are cutters you can get or even make to cut your own 21mm film using bulk 35mm, I was never successful at getting it done.

After realizing I had Vlad’s camera for nearly a year and hadn’t shot it, I figured I could probably make do with some 16mm film. After all, the height of the exposed image was 18mm, only 2mm wider, so including the extreme edges of the film, I’d only be losing a tiny bit of image above and below the frame.

If it’s not obvious already in this article, this camera is small. In the image to the right, I have it next to a half frame Canon Demi, which looks like a monster next to the Ajax. The fact that these two cameras both shoot the same size 18mm x 24mm images is impressive.

The top of the Ajax-12 is where you’ll find most of the controls. In the upper left corner is the shutter release which is externally threaded for a cable release which would have often been attached to this camera.

Next is the shutter speed selector with speeds 1/10, 1/30, 1/100, and Bulb.

Dominating the center is the wind up knob that is used to tension a mechanical spring which controls both the shutter cocking mechanism and film transport. A full wind of the camera when it was new was good for 15 exposures which is the recommended maximum number of exposures from a roll of film. Finally there is the manually resetting exposure counter, which goes up to 18, allowing for a few extra exposures.

There’s nothing to see on the back of the camera other than a large swath of body covering over the door. You can also see a side view of the winding knob, showing how much higher it sticks up than the rest of the controls.

The bottom of the camera has both of the rotating locks that both hold the back and bottom of the camera on, but also opens and closes the Ajax’s film cassettes inside of the camera. Unlike other cameras with “Leica style” door locks, the Ajax’s locks can very easily become misaligned to the cassettes inside of the camera. When this happens, the camera will not close correctly. In the image to the right, you can see the right lock isn’t totally latched. This would have needed to have been corrected before shooting the camera as it would have likely allowed light to leak in.

With the back and bottom of the camera removed, you can see into the film compartment. The Ajax-12 uses special cassettes that slide into their own film carrier which then is installed into the camera as a single unit.

There are a total of 5 pieces needed to load film into the camera. Two inner spools, two cassette shells, and the carrier. Without an original user manual or any English instructions anywhere on the Internet, I struggled mightily loading film into the camera. Making matters worse is that this obviously needs to be done in total darkness. Although I was using 16mm film, I cannot imagine using 21mm film makes it any easier. I’ll admit to only succeeding through trial and error. I had to cut four different strips of bulk 16mm microfilm before I finally got it right on the fourth try. If this is something you’d like to try yourself, all I can tell you is good luck!

The only other control on the camera is the aperture ring around the lens on the front of the camera. In the image to the left, you can see f/stops from 2.8 to 16 written in white paint on the black lens barrel. Changing f/stops requires spinning the chrome ring around the base of the lens. A small red dot indicates which one you’ve selected.

Normally at this point in a review I would show a picture through the camera’s viewfinder, but this being a camera designed to be used remotely, there is no viewfinder. Focus is fixed at 5 meters, which when using smaller f/stops gives a depth of field from about 2 to 8 meters. Infinity focus is technically not possible with this camera, but shooting faraway landscapes really isn’t what this camera was intended for. This range, even wide open allows for plenty of room to capture sharp images of people or things a short distance away from the photographer.

Being a camera that was intended to be used discreetly without anyone noticing, it needed to be easy, and for the most part, the designers accomplished their mission. Loading film is a challenge, but once it’s ready to go, wind it up, select a shutter speed and f/stop that gives you the best chance at a properly exposed image and fire away. The sound of the clockwork film advance is mesmerizing. I’ve always enjoyed shooting these wind up cameras, and the Ajax-12 is no different.

With such a unique design, specialized feature set, and the fact that I was using the wrong kind of film, the ultimate question is how were the images I got from it?

My Results

Knowing that the Ajax-12 was designed for unperforated 21mm film, I knew I would be faced with a challenge if I ever wanted to shoot this camera. I had a couple of ideas of where I could source some film, but none of them worked out. There are cutters available that allow you to run regular 35mm through and have the edges cut off leaving only a 21mm wide piece of film down the center, but those cutters are hard to come by and expensive.

After stewing for a better part of a year in how I was going to shoot this camera, I ended up deciding to take some 16mm microfilm and load it in the cassettes and hope for the best. The film I chose is called ACS Datalink, an archival microfilm stock which I previously shot in the KMZ Narciss, another Soviet subminiature camera. Sure 16mm film is not 21mm film, but shooting narrower film in a camera designed for something bigger isn’t exactly unheard of. I have personally shot 120 roll film in a 116 roll film camera, and 35mm film in a 127 roll film camera, so how bad could it be?

The above gallery represents seven exposures I got out of my one and only roll of film I loaded into the Ajax-12. Normally, you’re supposed to get 15 images on a roll, and based on the number of blank frames where the camera didn’t fire or were hopelessly blurry, I’d say I loaded the correct length of film into the camera.

Shooting a tiny spy camera from the hip is both easy and difficult. Easy in that you just press a button and that’s all, but difficult in finding something worthwhile to photograph.

Of the images above, the only one where I really felt like a Cold War spy was of the men playing basketball. I was standing about 20 feet away from them when I captured this image. The one of the little boy on the playground is blurry as he was rapidly moving side to side.

The double image is of a pond in which the camera strangely didn’t space the frames enough, so I scanned them together. I intentionally left the edges in the scans because I liked the look of the distressed edges which gave a sort of “vintage frame”.

Overall, I must say the images look great! With the 16mm film, I only lost about 2mm of exposed image since I was able to use the entire width of the frame instead of just 18 of the 21 millimeters. The OF-28T triplet lens delivered sharp images with just the right amount of contrast. The 16mm microfilm I used is normally rated between ASA 25 and 50 which allowed me to use the 1/100 shutter speed at f/8 for the entire roll and exposure was good enough.

I’ve since sent this camera back to it’s owner, but having seen what it is capable of, I really wish I had given it another go. I wish I could have gotten some actual 21mm film, perhaps in color to see what it could do, but the loading experience was so miserable, I don’t know that even if I had it as I write this, that I would have bothered.

The Ajax-12 is a truly wonderful piece of history. Whether you are into cold war history, photography, or into espionage collectables, there’s something to like about this camera for a wide range of interest groups. As a camera, it’s certainly neat, and as you can see, is capable of good images, but they’re not common and when they do show up for sale, demand a hefty premium. As a collector and user of old cameras, I don’t know that this would be at the top, or even the top half of my most recommended cameras, but it certainly is cool, and if you have a chance to own or even shoot one, I definitely recommend it.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://fedka.com/catalog/product_info.php?products_id=366

http://www.photohistory.ru/1207248179642549.html (in Russian)

https://www.cryptomuseum.com/covert/camera/f21/index.htm

http://ussrphoto.com/wiki/default.asp?WikiCatID=46&ParentID=1&ContentID=179&Item=F+21

Have you ever reported on the Zenit Sniper Camera (KE-12)? David C.

PS: When vacating a Tuslog office building being used in Turkey, I found a sniper camera metal case stashed in a wall space. The 50mm and 300mm lens and filters along with the sniper shoulder rest were in tact but the camera was missing. The lenses had Pentax type screwmounts but the lens quality was not great.

David, unfortunately I have never reviewed one of the Photosnipers. None have crossed my path, but maybe someday!

I bought an Ajax/F-21 from a guy in Moscow a couple of weeks ago. Now impatiently awaiting its arrival (I sure hope it’s operational!). Meanwhile I’m designing my own film splitter for 21mm. Your review has really increased my interest. Thanks!

It is a cool camera for sure and it would be cool to see some proper 21mm shots, although my 16mm film hack seemed to work well. My best piece of advice is to BE PATIENT when loading the camera. It takes a bit of getting used to!

That is truly one cool, and TINY, camera. Your photo of the “private park” sign gives a good indication of the sharpness of this camera’s lens. But the fixed focus range would not suit the Ajax for document copying, where the secret agent would be obliged to use a Minox.

If you’re interested at the internals of this camera, have a look at eBay listing for item number: 164517405591 An Ajax-12 fully dismantled, being sold for spares.

I thought this review wouldn’t give me GAS… but how wrong I was! That’s a seriously cool little camera. I guess it’s a good (bad?) thing that they’re fairly expensive on the Bay. I really don’t need more film cameras 😀