In the film world, there’s a general grouping of large format, medium format, 35mm, and subminiature film. In every category besides 35mm, there’s a variety of shapes and sizes of film. Large format can come in any size from huge 24×20 images all the way down to 5×7 sheets. Medium format came in at least 30 different roll film sizes from 127 to 122 to 130 to Kodak’s own 620 and 616 formats. Even in the small subminiature formats, there’s 110, Minox, 16mm, and even some specialized 21mm formats that have existed.

For a large part of the 20th (and 21st) century, when you say 35mm, you’re almost always talking about the kind that came in Kodak’s daylight loading type 135 cassettes. First released in 1934 with the release of the first Kodak Retina, Kodak’s new film format wasn’t actually new at all. Double perforated 35mm film had already been in use for nearly three decades in cinema and later, still film cameras. Both the Leitz Leica and Zeiss-Ikon Contax had used it as far back as 1925 and 1932 respectively. My review for the 1927 ANSCO Memo also used it.

All Kodak had done was come up with a cassette that held existing 35mm cinema film in a light tight package that could be rewound at the end of the roll, protecting the film inside until it could be developed. Kodak was smart enough to know that if their new format was going to be successful, it needed to be compatible with the Leica and Contax, so care was taken to design the cassette so that it would fit into those cameras without modification, even though they predated the new film format. Kodak hit a homerun with their new 35mm format as within a year, other companies such as Certo and Welta started producing cameras that supported it.

At the time, Kodak wasn’t the only company producing 35mm film however. Kodak’s biggest competitor was AGFA, and like Kodak, they also made their own cameras. Since all Kodak did was create a cassette for existing 35mm film, AGFA decided to do the same thing. Their competing format was called Karat film, and the first camera that used it was the AGFA Karat. Like Kodak’s film, Karat film used standard double perforated 35mm film. Unlike Kodak’s format however, Karat film worked in a cassette to cassette transport and didn’t need to be rewound at the end of a roll. Film would be fed from a supply cassette directly into a take up cassette immediately after an exposure was made, and there it would remain until it needed to be developed.

Karat film used a simpler cassette without a central spool that was easier and cheaper to manufacture, and since cameras that used it did not require the ability to rewind the film, Karat compatible cameras could be made cheaper as well. The downside however is that it wasn’t compatible with established cameras like the Leica and Contax, and due to the way the film advanced, no more than 12 exposures could be loaded at one time, down from 36 in Kodak’s film.

Sadly for AGFA, shortly after the time when Karat film and cameras hit the market, war broke out in Europe and people’s attention turned away from new developments in film. Kodak had just enough of a leg up in popularity that by the time Word War II ended, most everyone had forgotten about Karat film. Although AGFA would resume production of both their Karat camera and film, they would concede defeat in 1949 by releasing a variant of their Karat camera called the Karat 36 that used Kodak’s type 135 cassette. AGFA would continue to produce both versions of the Karat camera for a short while before abandoning Karat film altogether.

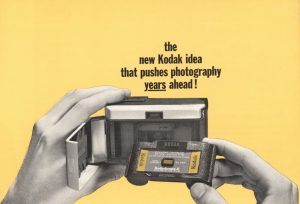

Fast forward a decade and a half, and film photography was more popular than ever before. Features like automatic exposure, motorized film advance, and fully flash synchronized shutters simplified film photography to where little to no knowledge of exposure was required to get a good image. Companies like Kodak and AGFA were looking for the next big thing in film, and in 1963 Kodak would strike first with a new format of film called type 126 Instamatic film.

This new format used film that was physically the same width as regular 35mm film, but instead of two rows of perforations, only needed a single perforation per frame to help identify the beginning of a new exposure. Instamatic cassettes came in a completely sealed plastic magazine that contained both a supply of new film and a take up spool. Installation into a camera merely required the user to open a door, drop in the cassette, close the door, and advance the film to the first exposure.

Once again, not willing to be outdone by their biggest competitor, AGFA responded with their own competing format which they called AFGA Rapid film. Curiously, rather than design a new and easy to use all in one solution like Kodak did, AGFA simply rebranded their original Karat cassette to cassette system with only one minor change, which was a small tab on the outside of the cassette to identify what speed film was in the cassette.

Karat and Rapid film were so similar that empty cassettes can be interchanged between Karat and Rapid cameras. Rapid film had the same benefits of Karat film as it was easier to load than regular 35mm film, supported the same exact film stocks, but it also had the same negative in that the length of film was shorter, limiting a full frame camera to only 12 exposures. As a slight consolation, Rapid film was released at the same time a huge number of half-frame cameras were popular in Japan so a few cameras were produced that shot half frame Rapid film allowing 24 exposures per cassette.

Although it seems to have been a half-hearted attempt at competing with Kodak, Rapid film saw more success than Karat film did as a variety of German and Japanese manufacturers supported the format. Besides AGFA, German cameras like the Voigtländer Vitoret and Pentacon Penti Japanese models from Canon, Minolta, Olympus, Fujica and several others all supported the format.

In a strange twist, around the same time AGFA was about to release East German film companies like ORWO and Pentacon created a variant of AGFA Rapid cassettes called the SL or “Speed Loading” cassette which was essentially the same thing, except the film came in plastic, instead of metal cassettes. SL cassettes were interchangeable with AGFA Rapid and Karat cassettes. A variety of East German cameras made by Pentacon, Beier, and a couple Soviet companies were produced that natively supported SL film.

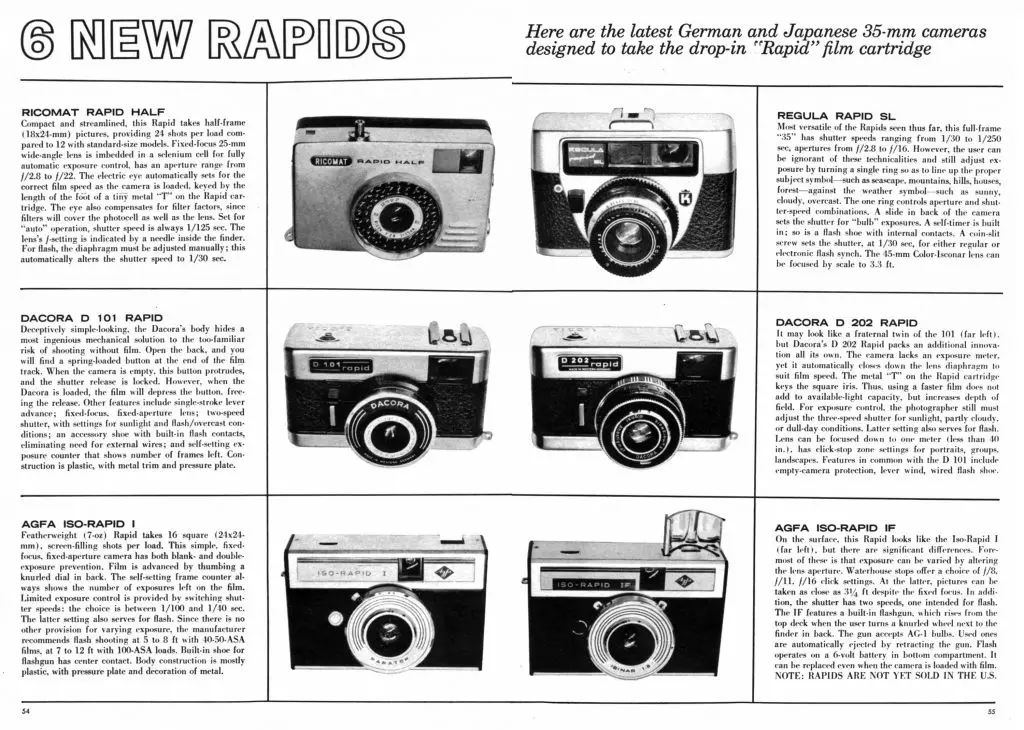

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings to you a variety of articles from the mid 1960s announcing the arrival of Rapid film. The two page spread below is from April 1965 and previews five new German and one Japanese model.

This first article is from the August 1965 issue of US Camera and is the most comprehensive. It gives a bit of history, some of which I’ve already covered here, but also previews a number of pretty neat models that I have personally never seen before. Models such as the Fujica Rapid D-1 were a scale focus model with auto exposure and a wind up clockwork film advance. The Canon Demi-Rapid was a cool half frame rangefinder with auto exposure and what is likely a 6-element 30mm f/1.7 lens. The Konica Rapid looks much like the Canon model but I cannot make out which lens it has.

Reading through the article, the most fascinating part to me was talk of an agreement that occurred in September 1963, in which a huge number of European and Japanese companies got together to agree on the specifications for Rapid film and cameras and that all member companies would share technologies and research with each other. The article says that this was the first ever collaborative agreement between German and Japanese camera makers. Even more impressive, some of the member companies were Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Asahi Pentax, and Zeiss-Ikon, all companies who would never actually make a Rapid film camera.

The second article is from August 1964, and is more of a preview of the system, which makes sense as it is the earliest featured here. It also tells some of the history of the format, even alluding to a very rare Bilora Radix Karat camera that was introduced in 1949, which I’ve never personally seen. This article spends a little more time talking about the various film emulsions from Ilford, Ferrania, and AGFA that were planned for the format.

Finally, this third article is from the January 1965 issue of Modern Photography and was authored by none other than Herbert Keppler himself. Unsurprisingly, this one is my favorite of the three as it cleverly talks about Rapid film hacks, most notably loading Kodak films such as Kodachrome and Tri-X into empty Rapid cassettes. Since the Rapid system was designed to compete against Kodak, it was unlikely any Rapid film would be sold with Kodak film in it, but the simplicity of the system makes manually loading unavailable film stocks really easy. Coincidentally, manually loading Rapid cassettes is the exact way you shoot these cameras today, you just need two empty Rapid cassettes.

If you don’t have two empty cassettes, the second “hack” is to find an old pre-war AGFA Karat (actually postwar Karat 12s work fine too) and use the Karat cassette. Although we know that Karat and Rapid cassettes were exactly the same, save for the film speed index tab, this fact is not mentioned in any of the above articles.

AGFA Isoflash Rapid C (1966)

Although both Instamatic 126 and AGFA Rapid film are no longer made, since both use film that is the same width as current 35mm film, they can be easily reloaded and used. AGFA Rapid cameras are very easy to reload as they simply require bulk 35mm film to be pushed into an empty cassette in the dark and loaded as normal. If you own a Rapid camera and have some bulk 35mm film, two empty Rapid, or even Karat cassettes, this is something you can do yourself.

A while back, I was gifted the AGFA Isoflash Rapid C below. This camera was produced around 1966 and was a very basic entry level model. It’s mostly plastic build and simple operation make it analogous to a 1960s version of a disposable camera. The camera can be reloaded of course, but otherwise it was the same.

I had intended to do a full review of this camera, but thought that it’s inclusion in this Keppler’s Vault about Rapid film might be more appropriate.

The camera is mostly plastic with a thin aluminum top and bottom plate and weighs a mere 195 grams without film loaded. The camera is fixed focus which means it relies on a wide depth of field to capture anything from about ten feet to infinity. The lens has an unlisted semi wide angle focal length (probably around 35mm) is likely a single element meniscus or possibly a doublet. There are no shutter speed or aperture settings, just a small lever with Sunny and Cloudy symbols that change the shutter speed between 1/40 and 1/80.

The camera does have double image prevention by way of a film interlock that will not allow you to fire the shutter without first advancing the film. You need film in the camera to test the shutter, but such a simple design is not likely to fail, so most cameras found today should still be in good working condition.

I did not test the flash as I had neither a suitable flash cube, nor the proper 5.6v Mallory mercury battery that goes into the base plate. For film, I loaded in a short roll of bulk Kentmere 100 as I knew this film had a wide latitude and would work well with the camera’s limited shutter speeds. The day I took it out shooting was heavily overcast, so it was a good match.

I’ve shot many simple cameras before, many with single or two element lenses, and I know that they can be anywhere from downright miserable to pretty good, and after seeing the results from the developed film, I am happy to report that the images from the Isoflash were definitely in the realm of good. These certainly wouldn’t impress anyone shooting a normal 35mm camera, but for an inexpensive plastic camera that was simple to shoot, the original owners of these cameras were likely very happy.

Without much control over exposure, I was limited to “Shade” and “Sunny” settings which was good enough to get properly exposed shots on a mostly cloudy day with occasional sunlight. If you wanted to try shooting this camera, I’d advise using something with good latitude like Kentmere 100. Exceptionally fast or slow films, or slide film would probably not work as well.

Because of it’s fixed focus design, the viewfinder is very simple, but also large and bright. With the semi wide angle focal length, you can fit a lot into the viewfinder. The camera’s squared edges would normally be an ergonomic concern, but the overall compact size, and light weight make for an easy to carry and use camera.

I enjoyed shooting the Isoflash more than I thought I would. When you don’t have to think about shutter speeds, f/stops, or even focus, you can just point the camera at something and shoot it, just like the term point and shoot suggests.

Rapid film, much like Kodak’s Instamatic was meant to be a simpler film than 35mm, and cater to novices who thought that extending a film leader across a film plane and attaching it to a take up spool was too much of a burden. Most Rapid models were of the scale focus point and shoot variety, with a few rangefinders, the highest spec of which was a model by Canon with auto exposure, a coupled rangefinder, and a fast 30mm f/1.7 lens.

For me, using Rapid film in a higher spec camera really doesn’t make a lot of sense, as it was aimed at the extreme beginner, who likely didn’t care about fast lenses or advanced features. Simple models like this Isoflash were a perfect match for the format, are still incredibly inexpensive today, and as you can see from the gallery above, are still capable of nice images. If you have an opportunity to pick one of these up for a couple bucks, as long as you have at least one cassette, I recommend giving it a chance!

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

Sometime in the late 1960’s, when I was attending college, I had added a Minolta Autopak 700 to my otherwise-Nikon 35mm set of cameras. It was OK, cheaper than a Kodak Instamatic 700/800, with similar features. The limits of Kodacolor-X/Kodachrome/Ektachrome/Verichrome Pan in 126 became apparent, since “available darkness” photos with ASA 80-125 film was limited, even with electronic flash.

I saw the Keppler article about the Rapid system, and soon acquired a Minolta 24 Rapid, which was a 24X24mm version of the Autopak 700. I noticed that there was a “tooth” on the Rapid cassette, which coupled with a spring-drive post in the 24 Rapid, which I took to be how film ASA speeds were detected. Using an exposure meter and cutting up pieces of Bamboo skewers, I discovered that I could step aside the ASA 64-125 limits to at least ASA 400.

I stuffed varying lengths of Tri-X Pan into the Rapid cassette, and “adventures in the dark” began. My findings? If you stuffed too long a strip of 135 film into the Rapid cassette, it would bind, the film would tear, and film chips would damage the camera. Eventually, I returned to the exciting world of the 35mm SLR, but the Minolta 24 Rapid is somewhere in storage, ready to be an interesting compact film camera again.;)

Patrick, I use my Minolta 24 Rapid frequently. The 24 x 24 format is unique (and gives you 16 shots on the short rapid roll–I can push 22 shots into the canister but I like being able to use the frame counter on the camera which counts down from 24) and the rangefinder and meters on them frequently survive (I have handled several). Varta’s 625U battery works well in them. Camera-wiki.org’s “Rapid Film” listing has the lengths of the tabs for each film speed on rapid cartridges, but you don’t need to hack the cassettes with the Minolta 24 Rapid. I have a couple of “D” cassettes, which are 100 speed and because the 24 rapid shoots both auto and manual, you can put 200, 400 or even 800 speed into the cassettes, take the meter reading, and then set up the shot manually a stop or two or three away from the reading. The lens is very sharp compared to the Agfa ISOflash in this article. It’s a cool little camera. The manual is available online.

Sorry, the frame counter counts down from 16, not 24.

Very interesting article. I heard of the Rapid system but never knew much about it. A fascinating dead end. Thanks for posting.

One minor point: large format film is more properly referred to as sheet film. The most popular size by far is 4 x 5 but I still have a box of 2-1/4 x 3-1/4 Tri-X from my old darkroom days.

Thanks for the history behind this format, Mike.

I have two cameras in my collection, never used by me, as I got them purely out of interest. The first acquisition, mid 1970’s, was the Fujica Rapid D1, which you mentioned. This is a half-frame model, so has the more user friendly double the number of exposures, but over and above its headline feature of a clockwork drive, it’s relatively sophisticated with its basic spec in that it combines fully programmed auto exposure, and fully manual settings for its four speeds, 1/30 to 1/300 sec, + B. DA is provided by a second clockwork mechanism which the user also has to wind. Given Fuji’s reputation for optical quality, I’d expect decent performance from the D1’s half frame negs, especially with medium speed b/w film.

The second camera is Agfa’s own Karat 12 with the four-element (uncoated) Solinar, and which I aquired a couple of years ago just for its quasi art deco looks. I was surprised at just how small it is for a FF 35mm film camera.

I have a Karat 12 in the collection with the same uncoated Solinar you mentioned. In fact, the image of the back of a Karat camera in this article showing both cassettes loaded is of that camera. It works perfectly, but I just haven’t had a chance to shoot with it yet. One of these days I’ll get to it and do a review! The Fujica Rapid D1 looks really cool. They made another model called the Rapid S2 that looks really nice too, but it’s really hard to find. I wouldn’t mind getting my hands on that Konica Rapid either. 🙂

Mike, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The S2 looks horrible to me.

Mike, the Canon Demi Rapid was Half Frame not full frame, Canon also made the Dial Rapid that was also Half Frame but looked like a regular 35mm compact rather than in the style of Canon’s other Dial Half Frame cameras.

Whoops! I missed that! I corrected it, thanks.

There are few other cameras not mentioned out there that take rapid or karat film. The American made Agfa memo from about 1940 was made in both full and half frame versions, and my favorite the Oehler Infra, one of the strangest cameras ever made in Wetzlar, it takes rapid/karat cartridges and shoots 24×24 square frame. The cheapest way to get more rapid cartridges is to buy Agfa iso rapid cameras on eBay, but they turn up occasionally, I found some expired rapid film at Goodwill once. I have enough I can keep a few loaded rolls on hand. A couple times I loaded a rapid cartridge in a dark bag, and at the same time created a short roll of regular 135 for testing cameras. Just snip off enough for a Agfa cassette and cut a new leader on the remaining film in the 135 cartridge. Most of the Agfa rapid camera shoot square frame. The iso mat model has a good triplet lens. The experience of shooting the Agfa rapid camera is a lot like shooting a Kodak instamatic, with the advantage of easy reloading with regular 35mm.