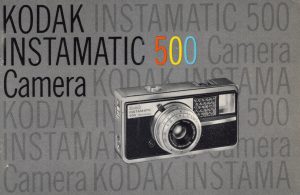

This is a Kodak Instamatic 500, a fully manual, but high end Instamatic camera built in Stuttgart, Germany by Kodak AG between the years 1963 to 1965. The Instamatic 500 was one of Kodak’s few Instamatic cameras built in Germany, by the same German division responsible for their premium Retina line of 35mm cameras. The Instamatic 500 had a fixed Schneider-Kreuznach Xenar lens and a coupled Gossen exposure meter with a match needle display in the viewfinder. The body of the camera was mostly cast metal with minimal use of plastic, making for quite a stout little camera. Although considered a premium model, every function, including the film advance was manual which is an asset today, as most Instamatic cameras are unusable due to degradation of their automatic electronics.

Film Type: Kodak Instamatic Type 126 Cassettes

Lens: 38mm f/2.8 Schneider-Kreuznach Xenar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 2.5 feet to Infinity with Click Stops at 4ft, 8ft, and 20ft

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 38mm Projected Frame Lines and Match Needle Display

Shutter: Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Gossen Selenium Cell

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and M and X Flash Sync, X-sync at All Speeds

Weight: 395 grams

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/02281/02281.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kodak Instamatic 500 was Kodak’s top of the line camera in their non-SLR Instamatic line. Built in Germany by the same people who made the Kodak Retina, the Instamatic 500 had a mostly metal body with excellent build quality, a good Schneider Xenar lens, a Gossen exposure meter, and full manual control. That the camera worked without a battery and didn’t require any type of motorized film transport subject to fail over the past half century, these are some of the more usable Instamatic cameras today and adapt well to using regular 35mm film. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

When the Eastman Kodak Company released their new type 135 daylight loading 35mm film in 1934, the idea of a drop in roll film that could be done without a dark room was ground breaking. It opened the doors to new types of cameras and photographers who otherwise might not have been interested, or able to get into photography. Simply open the camera, insert a new cassette, extend the leader and attach it to the take up spool, close the door and shoot. It was that easy.

Over the next 25 or so years, Kodak’s film became the dominant type of 35mm film. There were alternatives, but none that had the immediate popularity of type 135. Throughout the 20th century, cameras became more advanced, yet simpler at the same time. With new features such as automatic exposure, photography continued to appeal to novices who knew little to nothing about photography so in the early 1960s, Kodak thought it was time to update 35mm film and come up with something that was not only new, but even easier to load and would totally eliminate any chances of light leaks ruining the film.

In early 1963, Kodak would announce a new 35mm film format that would be called Instamatic, or type 126 film that would come in a plastic cassette that contained everything needed to advance the film from the supply to the take up side. The film would be protected both while loading and removing from the camera so that your images wouldn’t be accidentally ruined if exposed to light. By far, the most appealing feature of the film was how easy it was to load. You simply dropped the entire cassette into the back of the camera and closed the door. There was no film leader or take up spools to deal with.

Because of the design of the new Instamatic cassette, it wouldn’t be backwards compatible with other 35mm cameras, so before anyone could buy the new film, a new range of cameras needed to be created. Kodak knew this film would appeal mostly to novice photographers, so the first Instamatic cameras were very basic cameras with very few, if any manual controls. The Kodak Instamatic 100 seen to the left came in a mostly plastic body, with a fixed focus single-element plastic lens, no aperture control, only two shutter speeds, and support for flash cubes. At a price of $17.95, which compares to about $150 today, the Instamatic 100 was an inexpensive introduction to the new format.

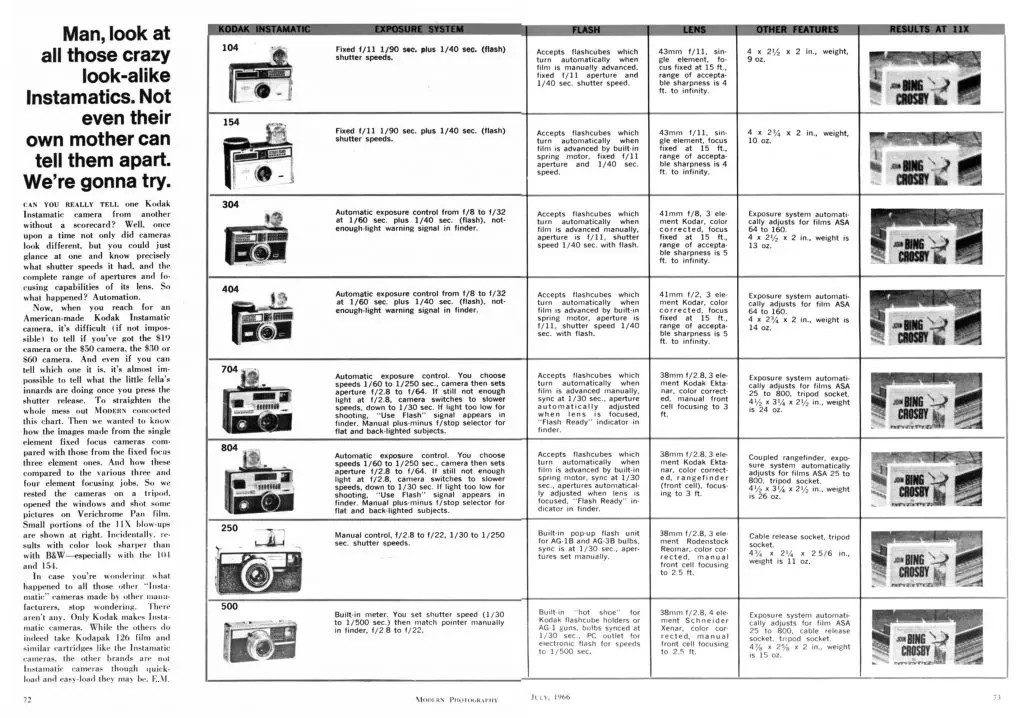

Other models in the series shared a similar body, but added features like better lenses, auto exposure, spring wound motorized film advance, and eventually a full focus lens.

While the primary goal of Instamatic was to simplify photography to make it more appealing to the novice, Kodak thought that perhaps there would be a market for their new film with more serious photographers. In order to do that, they would need a much more sophisticated and capable camera than a mostly plastic point and shoot model.

Kodak knew that it would likely be a tough sell to convince established professional and semi-pro photographers to abandon 35mm, so to maximize it’s appeal, the company turned to it’s Kodak AG division in Stuttgart, Germany, where the Kodak Retina series was developed, to create an a high end Instamatic camera.

This camera would be called the Instamatic 500, likely because of the camera’s top 1/500 shutter speed, and would come in a compact and clean metal body, with a 4-element Schneider-Kreuznach Xenar lens, a shutter with a 5-speed Compur leaf shutter, a Gossen branded exposure meter, and full manual operation.

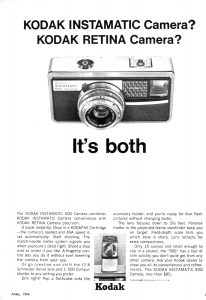

The idea of a high end Instamatic made by the same people who also made the Retina was not lost on Kodak’s marketing team as the ad to the left from April 1966 clearly connects the two together.

Feature for feature, the Instamatic 500 most closely resembled the Retina I BS, which had a very similar 45mm f/2.8 Schneider Xenar lens, a Compur leaf shutter, Gossen exposure meter, and was scale focus. Other than the differences in film format, the only other differences were the Instamatic had a flash cube socket and lacked slow speeds below 1/30 whereas the Retina was flashless and went down to 1 second.

When it first went on sale, the price for the Instamatic was $94.50, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to around $800 today. This price, while certainly not cheap, would have not been out of the question for a serious photographer looking to try out a German made camera with a new film format.

The Instamatic 500 was a very compelling option for someone wanting a portable, yet capable camera that could easily fit into a small coat pocket, and at a weight of less than 400 grams wouldn’t weigh anyone down during long shooting sessions. When storing the camera, it has a clever feature in which you can retract the shutter inside the camera body by pressing an unlableed button on the bottom while pushing in on the lens. This reduces the thickness of the camera even further, adding to it’s compactness. While the camera’s list of features and German reputation helped make it attractive to advanced amateurs, it was the camera’s fully manual and mechanical operation that was the most interesting.

All other Instamatic cameras either had simple controls that didn’t allow for much control over shutter speeds, f/stops, or focus, and for the ones that did, all used some type of automatic exposure. The Instamatic 500 worked entirely without batteries, had a film advance lever for manual film advance and allowed for fully manual operation. The Gossen exposure meter was just there to make recommendations using the match needle display in the viewfinder.

Although this likely wasn’t Kodak’s intent back when this camera was first created, it’s this full manual control that makes the camera most appealing today. The good build quality of the camera, combined with it’s lack of dependence on electronics to work, means that most examples should still be in good working operation today.

It is not clear how many Instamatic 500s were sold, but the presence of ads at least three years after it’s introduction suggest a pretty good product life. The camera would eventually be replaced in Kodak’s product lineup by both the Instamatic 700 and 800 series cameras which although not built in Germany, had good lenses, and a wide range of features, some including a rangefinder.

Kodak’s decision to push Instamatic film into the advanced amateur market proved to be wise as the success of the Instamatic 500 and the later Instamatic Reflex SLR prompted other manufacturers to release their own advanced rangefinder and SLR models using the format. Models like Minolta’s Autopak 700 and 800 series, the Rolleiflex SL26 and Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex 126 proved that there was crossover appeal for more advanced cameras with an easy to use film system.

Instamatic film would remain popular throughout the remainder of the 1960s and well into the 1970s, but a combination of advancements in 35mm film and Kodak’s introduction of the similar, but much smaller Pocket Instamatic 110 film format caused demand for it to decline. By 1977, only the simplest of models were still being made, with the last, the Instamatic X-15F discontinued in 1988. Kodak would continue to produce Instamatic film for another ten years after that, but completely stopped production in 1999.

Today, there is a small, but growing interest in Instamatic films. Although no fresh emulsions are made anymore, creative hobbyists have found ways of reloading original cassettes with regular 35mm film which is the exact same size, and other than the film perforations, can be shot in some models. In addition to reloading original cassettes, 3D printed alternatives such as the Fakmatic help simplify the process even farther. Not every Instamatic camera reacts well to reloaded 35mm film, but many, including the Instamatic 500 do, making them compelling options.

My Thoughts

Back in 2018, my friend Adam sent me a Kodak Instamatic 714 he had preloaded with some bulk 35mm film into a repurposed Instamatic cassette for me to try out. I shot the entire roll, but found out that the camera had failed. Despite Adam’s best efforts to get it working for me, I ended up with an entire roll of unusable pictures which soured me on Instamatic cameras.

Early last year, I picked up the Bell & Howell Autoload 342, a Canon made Instamatic camera that had a really curious focus device called a delta rangefinder that intrigued me enough to give the format another go. Using Adam’s instructions, I hand loaded some film of my own into an empty cassette and took it out. After seeing the results I got from it, I had warmed to the idea of trying out more cameras like this.

Repurposing original cassettes is doable, but depending on which cassette you use, some are harder to open than others, and almost always require you to tape up the seams to protect the film inside from light leaks. As an alternative, I decided to order the Fakmatic, a 3D printed Instamatic cassette and spool that is designed to be taken apart. The Fakmatic helps eliminate light leaks both by relocating the seam away from the edges, but it also removes the clear window that would have been used to read exposure numbers on the backing paper of film, meaning you can load naked film into the cassette without messing with the paper.

The makers of the Fakmatic encourage people to stick with simple Instamatic cameras like the Instamatic X-15F or Instamatic 133, but that wasn’t too exciting for me, so I tried one of the highest spec cameras I could find, the German made Instamatic 500. As I write this, I’ve used it successfully in other cameras, including the Instamatic Reflex SLR, but I’ll save those comments for a future review.

Advertisements from 1966 suggest the 500 is both an Instamatic and a Retina camera. Being made in Stuttgart, West Germany, alongside the Kodak Retina series, it makes sense that Kodak would capitalize on this in their advertisements, but after holding one, from a pure tactile standpoint, the Instamatic 500 definitely has a “Retina-like” feel to it. The camera has a mostly metal body, with only the door and front body covering in plastic. The perimeter of the camera is a wide piece of chrome trimmed metal with a deep shine to it, reminiscent of 35mm Retinas.

The camera has a minimalist design that starting with the top plate features only the flash hot shoe and cable threaded shutter release button. The location of the button, combined with the compact body with rounded edges is comfortably located and in easy reach of your right index finger.

The bottom plate of the camera has an offset 1/4″ tripod socket, that on most cameras I would suggest should have been located in the center to help balance the camera when mounted to a tripod, but the light weight of the Instamatic 500 makes this less of an issue.

Directly below the lens is an unlabeled button that I’ll admit, I couldn’t figure out it’s purpose until I read the camera’s manual. This button is used to retract the shutter and lens partially into the body in an effort to make the camera as compact as possible when not in use. With the lens retracted, you are unable to change shutter speeds on the shutter as this part is no longer visible. The shutter release will also no longer function. In the double image to the right showing the lens both retracted and extended, only the shutter speed dial is not visible when retracted.

With the lens retracted, you save about half an inch of space, which if I’m being perfectly honest, isn’t that much. Compared to a Leitz Elmar 5cm f/3.5 collapsible lens, it is less than half the distance of that lens when collapsed. While I applaud Kodak AG’s efforts to make the camera as small as possible, I wonder how many original owners of this camera ever used this feature, or even knew what that unlabeled button was for.

The sides of the camera have recessed strap lugs that conveniently let you attach a neck strap without anything protruding out of the side of the camera when not in use. On the camera’s right side is the release latch for opening the film compartment.

The left hinged door swings open and locks into place which helps loading film as it prevents the door from flapping shut on you like sometimes happens with other Instamatic cameras.

Inserting an original Instamatic cassette is uneventful, just press it into position and close the door. If you are using the Fakmatic, there is one thing to be very careful of, which is the geared sprocket that engages the teeth on the cassette is on the bottom of the camera, unlike most other Instamatic cameras which have it on the top. The best explanation for this that I can come up with was to make it easier to access with the camera’s bottom plate film advance lever. When loading film into the Fakmatic, you must make sure the red spool is upside down with the teeth facing the bottom before assembling it, otherwise the camera will never advance the film. Other than this, film loading using the Fakmatic is like in any other camera.

As mentioned, the Instamatic 500 has the film advance lever on the bottom of the camera, within easy reach of your right hand thumb. A full advance of the lever is only 90 degrees and when using real Instamastic film, is advanced multiple times until it locks. When using reloaded cassettes with 35mm film, you must give it a single wind, then cover the lens with your hand, fire off a blank exposure, and then wind a second time before making your exposure. Failure to do this will result in badly overlapping frames.

Up front, the Instamatic 500 has it’s strongest resemblance to the Retina, as it shares a very similar Schneider-Kreuznach Xenar len as found on cameras like the Retina IB S. Focus is changed by rotating the front ring, with shutter speeds from 1/30 to 1/500 plus Bulb behind it, followed by the aperture ring closest to the body. As is the case with most cameras with German lenses and leaf shutters, the focus, shutter speed, and aperture rings all move smoothly and without any wobble or grit.

The viewfinder is large and bright, featuring a pink tinted image with projected frame lines to indicate a 38mm focal length. The frame lines have parallax correction marks which are to be used when composing an image closer than 4 feet.

Beneath the main viewfinder is the meter readout from the selenium Gossen meter. An analog needle swings between a -1 and +1 mark, and when centered should produce accurate exposure with the selected shutter speed and aperture settings. If you intentionally want to over or under expose the shot, select a combination that appropriately locates the needle at either of the +1 or -1 locations.

A Note About Film Speeds: Unlike most metered cameras, the Instamatic 500 does not have a setting to calibrate the meter for different film speeds. Kodak designed Instamatic cassettes to have a special notch on the plastic shell of the camera that the camera can detect to automatically set a film speed. The user’s manual of the Instamatic 500 says the camera can automatically detect speeds from ASA 25 to 800. If you are reusing original Instamatic cassettes with reloaded film and plan on using the meter, you must take care to load film with the same speed as the cassette was made for. If you are using the Fakmatic, which does not have the provision for film speed, the meter defaults to ASA 800. For this reason, using the Fakmatic with anything slower than 800 speed film will render the readings from the meter useless.

The Kodak Instamatic 500 is a very compelling camera for any collector, but especially those looking to try out Instamatic film today. It’s battery-less operation and full manual control makes it more usable than many of Kodak’s other automated models, plus with good German optics and a quality shutter means that it is capable of excellent images. If I had to pick one camera to use today as a representative of the entire history of Instamatic film, this would be it.

My Results

The Kodak Instamatic 500 was my second camera to use the Fakmatic adapter I had purchased from the Film Photography Project, so I was already pretty certain it would work fine in this camera. For my first roll through it, I used some bulk Kodak Vision3 50D motion picture film. This is an ASA 50 speed daylight balanced film that I’ve shot numerous times with other cameras, and with the Instamatic’s wide range of shutter speeds and quality Schneider lens, I felt it would be a pretty good option, plus, I just really like the look of images shot on it.

Kodak Vision3 50D is a motion picture film, which means it has a special Rem-Jet coating on the back of the film which protects it while traveling through a cinema film camera. While these types of films can be shot in regular still film cameras, the Rem-Jet coating must be removed during the development process.

There are a number of ways to do this, from hand rubbing baking soda onto the film, or you can order an ECN-2 kit that is designed for Rem-Jet backed films which removes it for you. I chose the latter, and developed the roll using a $20 kit found on Etsy by a seller named cosofart. The kit costs $20 and includes everything you need except fixer, which I already had. The Film Photography Project has recently started offering an ECN-2 kit as well, but I have not had a chance to try it myself.

Developing the film was easy as all I had to do was follow the included instructions. When the film dried and I was able to scan it, I found the colors to be pleasingly warm, which suited the fall foliage and beach scenes in which I shot the film. As I had expected, the Schneider-Kreuznach Xenar lens performed brilliantly. This isn’t the highest spec lens ever made, but it’s sharpness and detail are more than enough for the 26mm x 26mm images that this format produces.

Shooting 35mm film in an Instamatic camera can sometimes be problematic, even with the Fakmatic adapter, because of the double row of perforations on 35mm film that isn’t there on regular Instamatic film. For many cameras like the Instamatic 500, this can be overcome by advancing the film twice, firing a blank exposure by covering the lens every other frame.

On the Fakmatic’s official website by the company who made it, they reference the Instamatic 500 needing the red take up spool installed upside down, which I can confirm works. The Fakmatic itself goes into the camera normally, but when installing film into it, you need to make sure the side of the spool with the teeth is facing down. I emailed them suggesting they simply 3D print the spool with teeth on both sides, but they never responded to me.

The Instamatic 500’s traditional film advance lever is an asset in this case as it improves compatibility with 35mm film. I’ve found that cameras like the Kodak Instamatic 804/814/X90 with an automatic motorized film advance really struggle with it.

Back to the camera itself, using the Instamatic 500 is a joy. I agree with the statement in the advertisement earlier in this article that says the camera is like an Instamatic Retina, as the camera very much has a German level of quality to it. Although not very heavy, the camera has a solid all metal feel, a very large and easy to use viewfinder, an accurate Gossen light meter, and I already spoke of the quality of the lens.

I really enjoyed using this camera, more than I thought I would. Although lacking in a rangefinder, the 38mm lens allows for a very wide depth of field that when shooting outdoors in good lighting makes focusing very easy. The lens’s three zone focus click stops are all you needed for the majority of outdoor shots. Loading film into the camera using the Fakmatic adapter is not difficult, but it isn’t quite as simple as popping in a fresh roll of 35mm film, meaning I likely won’t use this camera too often, but so far, of all the Instamatic cameras I’ve tried, this one is definitely my favorite.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Instamatic_500

http://brucevarner.com/Kodak_Instamatic500.html

https://vintagecameralab.com/kodak-instamatic-500/

http://elekm.net/pages/cameras/instamatic-500.htm

https://manondamoon.com/2018/04/02/a-camera-the-kodak-instamatic-500/

https://manondamoon.com/2018/04/02/usage-and-repair-notes-for-instamatic-500/

http://planetstephanie.net/2011/10/11/instamatic-500-by-kodak-ag/

I think it was back in 1965 – 66 my parents took advantage of a Bank program where they opened a new savings account and got a free Kodak Instamatic camera. I do know that they did this in the name of us four kids and of course their names as well. This was the type camera we all got. Other banks in the area jumped on this idea and offered a simular camera by Keystone and other Kodak models and brand names all so simular that they were hard to tell apart other than the logo or model number. This was a promotional gimmick that actually offered a useful product. I still have my camera just no film… ? Why did the 126 cassette ever go out of vogue? It was easy to use and offered in a slide or print film format. It also gave people access to inexpensive snapshot photography. David C.

Did you need to load the FakMatic cartridge in a changing bag. and empty it the same way (i.e. from the cartridge in total darkness into the developing tank)?

Yes, it all needs to be done in darkness as you are putting in and taking out unexposed 35mm film into the adapter. It’s no different than having to load film into a developing tank. For the record, although I do own a film changing bag, I have a downstairs bathroom in my house with no windows, so when I close the door and turn off the lights, the entire room is pitch black where I do this sort of thing. I find it much easier to operate in a room rather than inside a bag.

A long time I was so crazy to these 127film & half-frame cameras! (Kodak Instamatic 500, Yashica Half 1.4, Fuji TW-3, Canon Demi 17…etc)

In the end I killed these and modded lens guts into E-mount on my Sony APSC camera. 🙂

If they were going to make a new easy load cartridge camera, I think they would have done better making one in a larger size. Something similar to a cartridge loading 127 film size, which would be far easier to load that roll film. About halfway between 35mm and 120 size. That would have done better with semi pros and pros.

I just picked up a 500 and enjoyed this review! I have not ordered a Fakmatic and will likely get a pre-reloaded cartridge instead, as I hate reloading film—and I don’t process it myself either. But I wanted to add something of a correction to this statement:

‘If you are using the Fakmatic, which does not have the provision for film speed, the meter defaults to ASA 800. For this reason, using the Fakmatic with anything slower than 800 speed film will render the readings from the meter useless.’

An accurate meter reading at 800 can be useful with any other film speed if you just do a little calculation—which is another reason having all manual controls on this camera is such an asset!