This is a Yashica T AF, a 35mm fully automatic point and shoot camera made by Kyocera of Japan starting in 1985. The Yashica T was the first in a long running Yashica T-series of cameras that all came with a Carl Zeiss Tessar T* lens. At the time this camera was made, Kyocera owned the rights to the Contax brand name which they acquired when they purchased Yashica, along with the rights to use Zeiss lenses. Although an otherwise typical 1980s fully automatic point and shoot, the Yashica T was desirable for it’s lens, with later versions being extremely sought after today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35mm f/3.5 Carl Zeiss Tessar T* coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity, Fully Automatic

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 35mm Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Programmed Electronic Shutter

Speeds: 1/30 – 1/700 seconds

Exposure Meter: Silicon Photo Diode, Programmed Auto Exposure

Battery: (2x) 1.5v AA Batteries

Flash Mount: In-Body Pop Out Flash

Weight: 260 grams

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/YashicaTAFManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Yashica T AF was the first in the Yashica T-series a family of otherwise ordinary 35mm point and shoot cameras produced by Kyocera using the Yashica brand and Zeiss Tessar lenses. Although sporting excellent optics, the camera doesn’t offer anything more or less than other point and shoot models produced by other Japanese A-list companies like Nikon, Canon, and Minolta. The Yashica T AF produces excellent images with a mid-80s boxy aesthetic that people either love or hate. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.0 | ||||||

History

If you like to keep up to date on the current happenings of the film industry, you’ve likely heard the name Yashica a number of times the last couple of years as the brand has been resurrected by new owners who have hoped to tap into increasing demand for analog film by re-releasing modern takes on cameras like the Yashica MF-2, or one of their point and shoot disposables. The company even has plans (God…no) to re-release a 35mm version the classic Yashica-44 TLR.

This article is not about that Yashica.

At one time, Yashica was a major player in the Japanese photo industry releasing some of the best medium format twin lens and 35mm cameras on the market. Yashica’s mid-century roots can be traced back to two separate companies who would later merge. The first, was Yashima Seiki Seisakusho who was formed shortly after the end of World War II making a variety of optical products and accessories.

In 1953, the company would release it’s first camera called the Pigeonflex, a 6×6 TLR in the style of the German Rolleicord. The Pigeonflex would be a popular seller and quickly elevate Yashima as a premiere Japanese camera maker. The Pigeonflex would evolve into the Yashicaflex, and eventually Yashica’s “alphabet” lineup of TLRs.

By the late 1950s, as popularity of twin lens reflex cameras started to slow, Yashima wanted to venture into the world of 35mm rangefinders and SLRs, but they had no experience building such a camera or the shutters they required, so in 1958, Yashima acquired the Nicca Camera Company who had been struggling financially and was on the brink of collapse. Yashima acquired Nicca, and with it, their expertise with 35mm cameras and focal plane shutters.

In the years prior to Nicca’s acquisition by Yashima, they were at one point the premiere maker of Japanese Leica clones. Second only to Canon in sales, Nicca rangefinders were more faithful copies to the Leica II and III rangefinders than anything Canon had made. In the early 1950s, Nicca had entered into a lucrative distribution agreement with the American retailer, Sears, Roebuck, & Company, and sold their cameras through Sears stores under the retailer’s Tower brand.

Nicca cameras were well built and economical alternatives to genuine German cameras, but these were the only cameras Nicca built, and without a wider portfolio of products, they could not survive the growth of other A-list Japanese companies.

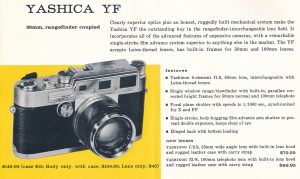

Later in 1958, Yashima officially became Yashica, the name used by the former’s TLR series, and the first two Yashica 35mm rangefinder cameras were released, the YE and YF. Shortly after, Yashica would release it’s first 35mm SLR, the Pentamatic. Using Nicca’s knowledge and resources, and with several exciting new models, things were looking bright for Yashica, but in a case of “too little too late”, Yashica still found themselves playing catch up with their domestic competition.

The Pentamatic series was well built, but sold poorly. Yashica realized that if they were going to stay relevant, they had to go down market. Later Yashica SLRs abandoned the Pentamatic’s unique bayonet lens mount, instead opting for the “universal” 42mm screw mount used by Pentax, Pentacon, and a few other companies.

Throughout the 1960s, Yashica tried to stay afloat by releasing an ever growing number of variations on the same 35mm SLR and rangefinder theme. In 1966, the Yashica Electro would make it’s debut to some considerable fanfare. The Electro had an all new electronic exposure system and electronic shutter. Together with good cosmetics and build quality and a great lens, the Electro was a good seller, allowing the company to stay profitable well into the 1970s.

By the early 1970s, Yashica was still getting by, but was far from the once dominant Japanese company they once were. Sensing a need to try something different, in 1973 Yashica would pair up with another struggling company. This time however, they did not buy another Japanese company, instead they entered into a licensing agreement with the Carl Zeiss Foundation in West Germany to build a new line of premium cameras using trademarks, lenses, and technology owned by Zeiss.

For Zeiss, they were struggling as well. In the years following World War II, what was once a single Zeiss-Ikon company in Dresden, split into two halves, one that remained in Dresden, under the control of the Soviet led, East German government, and the West German version of Zeiss-Ikon located primarily in Stuttgart. A legal battle between the two halves of the company allowed both to use the Zeiss-Ikon name, and share in some Zeiss branded lenses, but the Contax name belonged to Zeiss-Ikon Stuttgart. Zeiss-Ikon Dresden could use the name too, but only on products sold within East Germany.

Zeiss-Ikon Stuttgart would produce a new version of the pre-war Contax rangefinder until 1961 when the last model was discontinued. By the 1960s, the German camera industry had fallen on hard times, and in 1965, the once powerful Zeiss-Ikon merged with Voigtländer Braunschweig, yet another struggling German camera maker.

Together, Zeiss-Ikon and Voigtländer produced a series of mid to high end Icarex SLRs, and Vitessa rangefinders. The cameras were good, but did little to rescue either company. By 1970, Zeiss-Ikon stopped using the Voigtländer name on it’s products, and in 1972, sold it to Franke & Heidecke, the makers of the Rolleiflex.

After Zeiss’s sale of Voigtländer, instead of looking to merge with or reorganize it’s operations once again, Carl Zeiss, the owner of Zeiss-Ikon decided to exit the camera making business and instead focus on it’s lenses. In 1973, Carl Zeiss would enter into a licensing agreement with Yashica to allow them to build a new line of premium cameras using trademarks, lenses, and technology owned by Zeiss. For Zeiss, they could benefit from Yashica’s knowledge of electronics, modern factories, and cheaper labor, for Yashica, they hoped to break away from their “discount camera” reputation they had found themselves in over the previous decade. With German DNA in their cameras and the Zeiss name on their lenses, perhaps Yashica could finally compete in the mid to high end market.

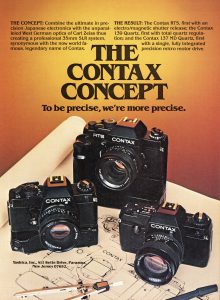

Two years later, an all new camera system was born with a new lens mount which would become known as the C/Y or Contax/Yashica mount. The first cameras to be released under this licensing agreement were the Yashica FX-1 and Contax RTS. The new Contax RTS was the first appearance of a Contax branded camera in over a decade and was a technological marvel. The Zeiss and Yashica partnership was mutually beneficial to both companies. Yashica would build the camera and be able to sell them with prestigious Zeiss lenses, and Carl Zeiss could license their trademark and build lenses for a Japanese camera that freed them from the high costs of building a camera themselves.

In 1983, Yashica would be acquired by Kyocera, a multi-national Japanese firm known for it’s role in the ceramics industry. In the years prior, Kyocera had been expanding into various consumer electronics markets, selling their own line of audio receivers, CD players, cassette decks, and speakers. At first, their ownership of Yashica saw few outward changes, as both Yashica and Contax branded cameras continued to be sold.

By the mid 1980s, as other camera makers like Minolta introduced auto focus SLRs, Kyocera decided to use the Yashica name solely for entry level point and shoot cameras, hoping to leverage mass production of cheap cameras over more expensive and slow to sell SLRs. The Contax name would continue to be used on mid to high end cameras, although on a smaller number of models.

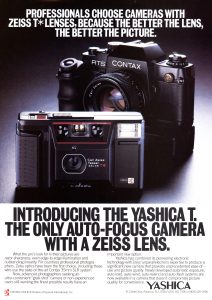

In what was a likely a last ditch effort to pair the Yashica brand with a premium camera, in 1985 Kyocera would release a new model called the Yashica T AF, which was an otherwise ordinary 35mm auto focus point and shoot, but it came with a 4-element Carl Zeiss Tessar lens with it’s T* color coating. Although 4-element Tessar-style lenses were not uncommon in this segment, none were branded as Zeiss lenses, so for Yashica, it was a pretty big deal.

In May 1985, Executive Photo & Supply in New York City sold the Yashica T AF for $112.50 and a version with a date back for $135. These prices when adjusted for inflation compare to about $275 and $335 today, a meager price for a camera a Carl Zeiss lens.

The formula worked as the Yashica T AF sold well enough to continue the series through 5 different revisions ending in the Yashica T4 Super/T5 in 1995, extending the life of the Yashica brand. Each camera used the same basic premise of a typical (for the era) 35mm point and shoot but with some variation on the Zeiss Tessar lens. Zoom versions of the camera were created with a 28-70mm Vario Tessar zoom lens, also with T* coating.

I am unsure of how many of each series sold, but there were enough that plenty still exist on the used market today. An abundance of these cameras has done little to harm their reputation as these cameras regularly fetch upwards of several hundreds of dollars on the used market, much higher than similar 1980s automatic point and shoot models. Whether or not the higher price tag makes them more capable than any number of similarly spec’d cameras is debatable, but at the very least, these are some of the most sought after 35mm point and shoot cameras ever made.

My Thoughts

In nearly every camera collector group I am a member of, there is constant talk about the rising cost of film cameras. Compared to 10 or even 5 years ago, you could easily pick up cameras for a small fraction of their original used prices in the pre-digital era. As photographers shifted away from film, large numbers of film cameras from the cheapest automatic point and shoots, to top of the line professional cameras were liquidated at rock bottom prices, sometimes even given away for free.

Recently, with increased interest in analog photography, those extreme deals seem to be fewer and far between with cameras that easily could be found for under $50 a couple of years ago, seeing prices double or even triple that today.

Of all the cameras who have seen their prices recently rise, there are a few models that have remained high, sometimes for good reason, but sometimes not. Of the expensive cameras that perhaps aren’t worth what they go for, one of the common models is are those from the Yashica T-series, specifically the Yashica T4 and T5. With sale prices exceeding $400, there must be something special about these Japanese cameras with German lenses, right?

Honestly, I’ll likely never know, because unless a reader of this site is willing to loan me their T4 or T5, I have no interest in attempting to acquire one at those prices.

The closest I’ve ever come came two years ago when I was browsing the shelves of a local camera shop and they had a “junk bin” that I was rifling through and I saw a small case with what was obviously a 35mm point and shoot camera in it, and upon opening it up and seeing that it was the first in the series, the Yashica T and it had a price of $10, I picked it up without attempting to see if it worked.

Although I realized that this being the first in the series and that it might not have the awesomeness of the later cameras, I still hoped that some magic would be evident on this model. Maybe a solid gold take up spool would await my gaze within the film compartment, or perhaps upon looking through the viewfinder, I would see images with a clarity never before seen in a point and shoot camera.

The reality is much less interesting. Putting aside the Carl Zeiss Tessar T* lens (what is with that asterisk anyway), which itself isn’t all that special considering by 1985 when this camera was sold, the Tessar formula was over 80 years old and had been copied by nearly ever lens maker who ever made lenses, the Yashica T AF is an almost carbon copy of dozens of other fully automatic Japanese 35mm point and shoot cameras from the same era.

Up top, the Yashica T AF has very little to show. An elegant white and red silkscreened logo is on the left, next to a sliding piece of plastic that covers both the bright red shutter release and gray self timer buttons, cleverly doubling as the camera’s power switch. With the buttons covered, the camera is essentially off. As was the case of most cameras of it’s type, the shutter release uses some sort of electromechanical switch which requires very little effort to activate, which is good in that body shake is almost completely eliminated as it requires so little effort to press, but bad in that barely a brush of your finger over it can result in unintended exposures. I did not try to use the self-timer, but it’s operation seems pretty straightforward. The only other thing we see is the automatic resetting exposure counter.

The bottom of the camera has a somewhat large rewind slider, the door for the AA battery compartment, and a threaded 1/4″ tripod socket. Unlike later 35mm point and shoots from the 1980s, the Yashica T AF will not automatically start rewinding the film at the end of a roll, you must activate this switch to get it to rewind, which is likely why they chose a larger slider than you might see on other cameras. The inclusion of the tripod socket is a nice touch that isn’t on all point and shoots, but isn’t all that necessary as the camera’s slowest shutter speed is still a hand-hold-able 1/30 second.

Also visible from the bottom of the camera is the ASA film speed selector which is on an angled face on the front of the camera beneath the lens. Five speeds from 50 to 1000 are manually selected and full stop increments. Some later versions of the Yashica T AF added DX film detection, but in those cameras, this switch is still present, allowing you to manually select a film speed only when using non DX-coded cassettes.

Also notice the sticker from Chicago’s Shutan Camera & Video, suggesting this is where this camera was originally purchased.

Looking at the camera’s back, in the upper left corner we have the flash activation slider, which pops out the electronic flash to the side of the camera. Next to it is a flash readiness LED which glows each time the flash finishes it’s charging cycle. The square viewfinder window has a small film transport indicator that jiggles as film transports through the camera.

On the left side of the door is the door release lever, and opposite of it is a rectangular peep hole which allows you to see what kind of film is loaded in the camera.

Film transports inside of the film compartment from right to left onto a fixed take up spool. The Yashica T AF as a quick load feature in which you extend the leader to the edge of the film chamber and upon closing the door, the camera does the rest. Two circular electrical contacts below the film gate would have been used for a version of the camera with a date back, but without that back do nothing. Finally, the door channels are deep enough to where light seals are not required, which is nice as any foam light seals that might have been used, would have deteriorated by now and needed to be replaced.

Although the flash is always visible from the front of the camera, to use it, you have to manually slide the gray switch on the back of the camera which will cause the flash to pop out to the side. This being a flash charging cycle, which takes about six seconds to fully charge and illuminate the flash ready indicator on the camera’s back.

Up front, the only control is the film speed slider beneath the lens. Later versions of the Yashica T AF had DX film encoding, but this one doesn’t. Whether it has this feature or not, the film speed switch is still there, still allowing you to manually select film speeds on DX equipped cameras using non DX coded film.

Under normal use, the lens is covered by a plastic lens cover, but will momentarily swing out of the way when firing the shutter. This feature allows the camera’s lens to remain protected at all times except the exact moment and exposure is made.

The viewfinder is typical of point and shoot cameras of the day, with projected frame lines with parallax correction marks to indicate the 35mm focal length of the lens. A small circle in the center is the auto focus area and must be centered on whatever you want the camera to focus on. One of three red LEDs will appear near the bottom of the viewfinder to indicated the detected distance. A single person indicates 1-2 meters, three people indicates 2-4 meters, and a mountain indicates 4m to infinity. A fourth red LED is of a lighting bolt that will illuminate when the flash is being used.

Despite their reputation, the Yashica T AF functions almost exactly the same as a huge number of other 1980s automatic point and shoot cameras. These models were designed to be easy to use, and they are. Having never picked one up before, you could hand one to a novice and they’d be able to shoot through a roll in no time.

My Results

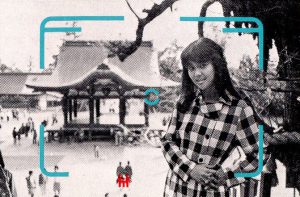

The Yashica T AF was sold as a premium option for someone wanting an easy to use camera to record family vacations, kids sporting events, and birthday parties. With it’s Zeiss Tessar lens, it should be capable of pretty good shots, but with the simplicity the camera was intended for, I chose a film that would have likely been used by someone who would have bought this camera in 1985, Kodak Gold 400. Kodak’s Gold color film was a staple of American families like mine in the 80s and 90s and it was the film most likely used to capture photos of my life growing up, so I thought this would be a good way to test the camera.

The million dollar question (actually, more like the multi-hundred dollar question) that everyone is asking about these T-series Yashicas is “how good is the lens?” To which I can answer it one of two ways:

The Yashica T-series has the best image quality of any 35mm point and shoot camera with a single focal length lens.

But I could also say:

The Yashica T-series has the same image quality of any 35mm point and shoot camera with a single focal length lens.

The reality is, that by 1985, the Zeiss Tessar formula was 83 years old. It was the most popular and widely used lens formula not only by Zeiss, but pretty much every other company that ever made lenses back then, and even still today. One of the reasons for the tremendous success of the Tessar is how good and how simple it is. With 4 glass elements arranged in 3 groups, you can obtain an image quality that is very sharp in the center, and only shows minimal signs of softness and a hint of vignetting in the corners. Sure, some cameras had 5, 6, or even 7 element lenses, but the amount of improvement those lenses offered were greatly offset by their cost, and something that the average person in the market for a 35mm point and shoot camera wouldn’t have wanted to spend.

That’s not to say it’s a bad lens, because it’s not. The images in the gallery above all look great! I don’t know if they would have looked dramatically better had I used a 6-element 50mm prime on an SLR, but they also wouldn’t have looked any worse had I used a 35mm point and shoot Canon, Minolta, Nikon, or any other number of camera makers putting 4-element lenses in their point and shoots

I give Yashica and it’s parent company Kyocera a heck of a lot of credit for seeing the value in the Zeiss brand. Putting a Tessar lens in this camera and also promoting the “Carl Zeiss Tessar” lens was a genius move and one that seems to have paid off as by 1985 when this camera was released, Yashica was an afterthought in the film community. Long gone were the days of their Yashica TLRs or even the modest popularity of the Yashica Electro series, yet the T-series seemed to have given the company one last breath of relevancy.

Even today, these cameras go for CRAZY prices. Not necessarily this first model, but later ones like the T4 and T5 $350 – $600 with asking prices even higher than that! Sure, they’re going to make great looking pictures, but not any better than a Kodak VR35 K14 “Medalist”, a Pentax PC35AF, or a Nikon One Touch AF3.

I’ve never had the pleasure of shooting any of the later models, but I see no reason to think that those cameras wouldn’t produce images exactly like this Yashica T AF. While that’s not a bad thing, for the $10 I spent on this versus what the later models go for, you can clearly see which one I’d prefer to keep.

Image quality aside, the Yashica T AF is unremarkable. Being from the mid-1980s, the camera has a boxy design that reminds me of my 3rd generation Camaro I had as a teenager. It’s bulky, and doesn’t have the best ergonomics, but no cameras back then did. I appreciated the auto focus distance confirmation in the viewfinder, but like many early auto focus cameras, it’s not especially accurate. Out of 24 exposures from my test roll, maybe 4 were out of focus. One of them, showing the Oldsmobile in the gallery above was shot in good lighting outdoors, so I can’t see why it would have missed it.

If you’re interested in these cameras to see what the fuss is, by all means, buy one as they make great photos, but if you are even considering spending the asking prices these go for, please click the Donate button at the top of this page and help me out as you clearly have more disposable income than I!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Yashica_T_AF

https://austerityphoto.co.uk/prelude-to-the-bling-boys-yashica-t-af-one-roll-review/

https://cameragocamera.com/2019/06/09/yashica-t-af/

https://filmandsensor.com/one-day-with-a-yashica-t-af/

http://wkoopmans.ca/notebook/?p=7609

http://www.brokencamera.club/blog/5zbzj9al49tdhw2engx53zap93gcmr

Just picked one of these (the date version) at an estate sale today for $6. Thanks for the detailed review! Looking forward to giving it a try soon!