This is a Zorki rangefinder camera, built in the former Soviet Union by Krasnogorsky Mekhanichesky Zavod (KMZ). Although not marketed this way when it was new, this example is known today as the Zorki 1C as it was the original generation Zorki rangefinder, and the third major variant. The Zorki 1C was built between 1951 and 1953. It was superseded by two additional variants of the Zorki 1 which remained in production until 1956. The Zorki was based on an earlier Soviet rangefinder called the FED whose factory in Ukraine had to be shut down during the war to avoid it falling into enemy hands. The original FED was a copy of the Leica II rangefinder, built in Wetzlar, Germany by Leitz. Although not built to the same quality standards as the German Leica, both the FED and Zorkis are faithful copies of the original that when found in good condition, are capable of not only good images, but recreating the Leica experience, at a much lower cost.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 Industar-22 coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: M39 Leica Thread Mount

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Optical Viewfinder and Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: Z (Bulb), 1/20 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe (no flash sync)

Weight: 534 grams (w/ lens), 416 body only

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/russian_pdf/zorki.pdf

How these ratings work |

The KMZ Zorki was one of the most successful lines of cameras ever made, with production numbers in the several million made. Although the cameras were originally built as economy versions of the Leica rangefinder, they are often unfairly compared against Leica’s build quality. If you can accept the Zorki for what it is, a discount copy of a great camera, you’ll find that it too, has it’s own greatness. When found in working condition, the cameras are as easy to use and as capable of the same quality of images as the camera it is a copy of. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall value, it’s 80% of a Leica for 80% less than a Leica | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.4 | ||||||

History

Prior to World War II, the Soviet Union had a variety of optical factories in places like Kharkov and Leningrad which had been churning out some variation of a German made medium format or 35mm camera. One of the core principles of the Soviet government back then was to be self-reliant and not have to import anything made in other countries so rather than import these cameras, they made them themselves.

Early Soviet cameras like the Fotokor-1 were simple 9×12 folding plate cameras made in Petrograd (later Leningrad and today St. Petersburg) that were low quality copies of German designs. The Fotokor-1 was produced between 1930 through 1941 at the GOMZ plant.

The most common 35mm Soviet cameras however, were ones based off the Leica II rangefinder. In the early 1930s, the Leica II by Leitz of Wetzlar, Germany was the most popular compact 35mm camera in the world. The Soviet Union decided they needed to have one too, and between the years of 1932 through 1934, no less than 3 different factories began work on their own copies of the Leica.

Soon, three different cameras, called the Geodezia FAG (pronounced like ‘fuuh g’), VOOMP Pioneer, and the Ukrainian built FED were all put into production. Of the three designs, the FED camera was given the most support and was the only to be continued past the 1930s.

The FED factory where the cameras were built was basically a boarding school that was designed as a youth rehabilitation center for orphaned children. The center was created by Anton Makarenko who was a Ukrainian educator who believed that troubled youths could be productive members of society by combining education and labor in a strict atmosphere. The center itself was named after Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky who was the founder of the Soviet Union’s secret police, known as the NKVD. The NKVD was the predecessor of the much more well known KGB.

Over time, FED would improve both the design and the reliability of the camera, but unfortunately, it’s location in Ukraine meant it was more prone to damage by German fighters in World War II. Anticipating imminent destruction, in 1942 the Soviet government transported much of the FED factory’s machinery to the city of Berdsk, Siberia for safe keeping. Plans for the FED camera were given to another Soviet optics factory called Krasnogorsk Mechanical Works or KMZ for short, in Krasnogorsk, near Moscow where they eventually started producing their own copy of the FED, which they branded Zorki (Зоркий), which loosely translates to “piercing” or “sharp-sighted”.

As predicted, the FED factory sustained heavy damage and it would take several years after the war was over to repair and return to producing cameras. Since the KMZ plant was protected from enemy forces, it only took a short order to start producing new cameras. In 1947, the first 35mm rangefinders were built by KMZ in Krasnogorsk.

Early copies of the KMZ Zorki still had the FED name stamped into the top plate. Dual FED/Zorkis were produced until the FED factory was restored, and resumed building their own cameras. From this point forward, KMZ built cameras would only have the Zorki name. The original Zorki would remain in production until 1956 and would go on relatively unchanged from the original FED design, which itself was a near copy of the Leica II.

As was the case with most Soviet cameras, the Zorki received many minor updates throughout it’s production run, none of which were ever officially given new names. Collector’s today, in an attempt to categorize the many different variations have come up with their own sub-models to differentiate the most significant changes, but even within a sub-model, there are sub-sub-models with very minor changes.

The camera reviewed here is known today as a Zorki 1C, produced between 1951 and 1953. The most obvious difference between a 1C and Zorkis that came before it is a painted cast metal trim that separates the body covering with the chrome top and bottom plates. This change was likely the result of a change in how the casting for the body was done at the factory. Earlier Zorkis and no FED or Leica camera have this trim, making them easy to spot.

By the early 1950s, Soviet cameras were increasingly being exported to western countries, including the United States. There is a belief among Soviet collectors that cameras produced by KMZ have a better build quality as more exported cameras were built there, and the Soviet Union wanted to prove to the world that they were a capable maker of photographic products. Whether there is any truth that KMZ cameras are better built, likely cannot be proven, but we do know that at least some cameras were exported.

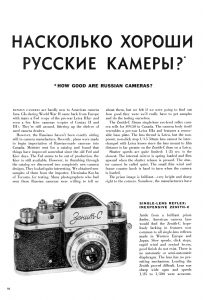

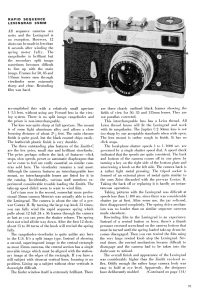

In a short article published in the November 1958 issue of Modern Photography, entitled “How Good Are Russian Cameras?”, author Herbert Keppler orders several Russian cameras from a Toronto, Canada importer called Ukrainska Knyha and tests both a Zenit-C and GOMZ Leningrad and offers his thoughts. Near the end of the article, he refers to two Zorki cameras that had a price of $99.50, but does not offer any further insight into which actual models they were. By 1958, when this article was published, the original Zorki model would have already been discontinued, so it’s likely a later model, possibly even a Zorki 3, or it could be left over stock of the original model that was just then making it’s way to Canada.

Beyond this short blurb, although I’ve read many times that Zorkis were exported out west, I could not find any advertisements for them to be able to guess a price. While under $100 probably seems fair for a Leica copy like the Zorki, to come up with a modern day price would just be guess work.

Throughout it’s 30+ years in production, the original Zorki would be redesigned and improved several times. Like the FED rangefinder it was based off, the Zorki too would also receive many changes, but both the Zorki and FED would continue to evolve separately from each other. By the end of production of the final models in each series, the later model FED and Zorkis would share little in common, other than the lens mount and film type.

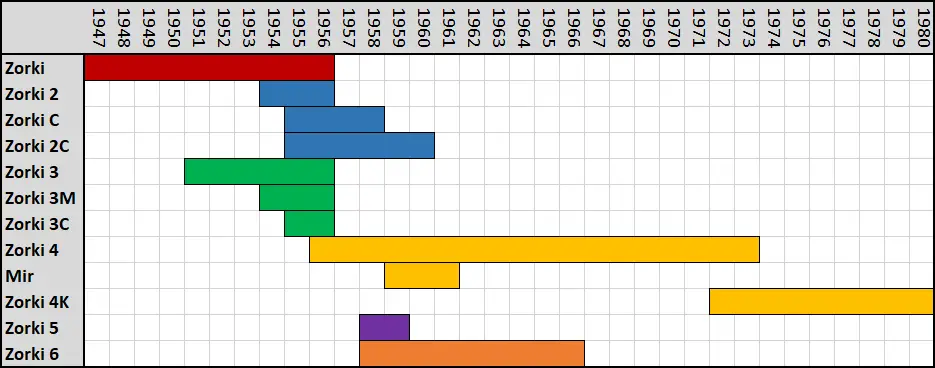

The names given to later Zorkis are quite confusing and were not always indicative to when each model was sold. Many different Zorkis were sold concurrently with others. Further adding to the confusion is that higher numbered Zorkis weren’t always more advanced or “better” than previous ones. The chart below represents all of the various models in the Zorki lineup. Note that there were three additional cameras to bear the Zorki name that are not related to these M39 screw mount rangefinders which I don’t consider to be part of the original Zorki lineage.

As you can see, the Zorki 3 was available three years before the Zorki 2, the Zorki 4/4K were produced well over a decade after the Zorki 5 and 6, and in 1956 you could buy as many as 8 different models at the same time.

The Zorki 3 and 4 series were the first models to have a combined coincident image rangefinder, and (excluding the Mir) were the only models with slow speeds down to 1 second. They all had hinged backs, and in the case of the 4K, had a lever film advance.

The Zorki 5 and 6 were both considered to be replacements for the Zorki 2-series but with a wider rangefinder base and a lever film advance. The Zorki 5 was most similar the Zorki C as it lacked both the self timer and hinged back.

Today, opinions vary among Soviet collectors as to which is the “best” Zorki since there really wasn’t ever one single model with every feature that was once available. The great thing about Zorkis though, and if I’m being honest, all Soviet cameras, is that most of them are still cheap enough that you don’t have to pick your favorite as you can just collect them all.

The entire family of Zorki rangefinders are collectable. Whether you like to use them or just keep them on a shelf, their build quality, while not the same as a genuine Leica, is still pretty good. If you can find one that’s been taken care of over the years, there is a very good chance it will still work, and if all you care about is to get a Leica-like experience, then they’re good enough for many people.

My Thoughts

Unlike most reviews where I start off this section with a brief story of how I got a particular camera and then going around it’s controls, I am going to do this one a little different as I assume you all know how to use a screw mount Leica or Leica copy. The Zorki was based off the earlier FED, which itself was a copy of the Leica II, so all of the camera’s controls are in the same location and work the same way.

It is no secret that Soviet cameras have been seen as inferior to their German counterparts since the first FED rangefinders rolled out of the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune in 1934. Where Leitz cameras were hand built by specially trained optical engineers and craftsmen and women, the original FED cameras were made by children. If you’d like to know more about the origins of the FED camera, check out their history in my review for the FED 2.

In the 1950s, the Soviet Union was more confident in their ability to manufacture cameras and lenses that the western world would want, so they began exporting many of their cameras to other European countries and even the United States. It is widely thought that KMZ cameras were better built as the Soviet Union did not want to risk exposing their products as inferior to others on the market.

Still, for a western photography to consider a Soviet camera, the price needed to be right, so these cameras were offered at a steep discount to their German competition. Perhaps people would see their products in a more favorable light, if they didn’t cost as much.

Knowing that a Zorki rangefinder was a less expensive alternative to the real thing, the ultimate question you probably want to know is, how do they compare, really? Before I give you my thoughts, I should share with you a different perspective on this exact camera, which I loaned to professional film photographer and self described Leica fan-boy, Johnny Martyr.

In early 2020, Johnny had made a comment that he never used a Soviet camera that he liked, but admitted that the sample size of cameras was quite small. Once he learned to love the real thing, he saw no reason to look at anything else. I thought it would make an interesting experiment to send him three of the best Soviet cameras I had in my collection to get his thoughts. One of those three cameras was this very same Zorki 1C which he wrote about quite extensively in April 2020. I definitely recommend checking out Johnny’s review as he gives what I think is a very fair look at the Zorki from someone who professionally shoots screw mount Leicas.

Of course, this isn’t Johnny’s blog, so for my thoughts, I decided to look at the Zorki and see how it fares to the real thing in four categories:

- The Shooting Experience

- Build Quality

- Value

- The End Result

The Shooting Experience

The Zorki is based off the original FED rangefinder, which itself was a copy of the Leica II. The shape and size of the body is the same, all of the camera’s controls are placed in the same exact locations, and the way the controls and viewfinder work are the same. Loading film is the same, attaching and detaching lenses is the same, both cameras support the same lenses (early FED rangefinders do have a different pitch to the lens mount so they are incompatible with regular M39 lenses, but that doesn’t apply to the Zorki), and both support the same kinds of photographic film.

There are some very minor variations such as with most Soviet lenses attached, the focus arm is in a slightly different orientation at infinity, but this is hardly anything that would affect anyone while shooting.

Call it what you want, a copy, a rip-off, a forgery, a knock-off, a carbon copy, etc. Simply put, when it comes to how you use a Zorki compared to a Leica, it is the same.

Build Quality

This ones pretty easy as the overall build quality of any Zorki, including the FEDs, is simply not up to par with the German built Leica. While Oskar Barnack’s design is one of the reasons Leicas have been so successful, the camera’s build quality and reliability was also a factor, and a camera originally built by children and then moved over to a multi-purpose manufacturing plant during a war, simply isn’t going to live up to the rigorous quality standards of the best of what Wetzlar had to offer.

But there’s more to explore here than to simply declare the Leica the better built camera and move on. In his look at the Zorki, Johnny Martyr picks up on differences such as obvious machining marks on the Soviet camera not present in the original, that the quality of the chrome is a bit rougher, inconsistencies in the thickness of the engraving on the top plate, shutter speed dial, and exposure counter, the angles and curves around the edges are not the same, and that the film compartment has more rough edges and is less refined.

He’s not wrong. A while back, I read an article comparing a genuine Rolex watch to some of the better fakes out there. I don’t collect watches, but I guess years ago fake Rolexes were easy to spot from 10 feet away, but that lately, counterfeiters have gotten better at getting closer to the real thing. The article says that if you know what to look for, despite improvements in quality of the fakes, there are still many easy ways to tell the difference. Like the Zorki, the Rolex copies have inconsistent chrome or gold plating, the engravings are thicker and less precise, edges are sharper and less refined, and things that should be knurled or textured aren’t, or things that shouldn’t be, are.

If we know that Zorkis are less refined than Leicas, does it actually make any difference in how the camera performs? Before I answer that, it’s worth mentioning that there is a functional difference between reliability and condition. I have not handled anywhere near a sample size large enough to provide any meaningful statistics regarding how well Leicas and Zorkis have held up over time, but it can be assumed that at least a percentage of both cameras can suffer the rigors of time equally. In my review for the Leica Ic, although the shutter worked, the curtains were loaded with pinhole light leaks. The Leica IIIb that I used in my Wehrmacht Leica article had a completely inoperable shutter and wouldn’t fire at all. Does that mean that all Leicas will have pinholes or bad shutters? Of course not, but it’s worth mentioning that whichever camera you are talking about, no camera was designed to go over half a century without being serviced. All of these cameras are very old and well beyond their intended end of life dates, whatever they may be.

Condition aside, I think the Zorki has just as much of a chance to be found in working condition today as any Leica. In fact, in Johnny’s comparison of my Zorki vs his Leicas, he noted that the rangefinder patch and viewfinder of my Zorki held up better than his IIIc, which needs a new beamsplitter, but on par with his 1930 Leica.

Coming back to build quality, yes, I definitely agree the Leica is the more refined machine, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Regardless of which camera you are talking about, I do not believe there is any meaningful difference in your odds of finding a Zorki or a Leica in ready to use condition, without needing some level of service.

Value

I am purposely talking about Value immediately after Build Quality as that is almost always the Soviet camera collector’s rebuttal to any claim that Leicas are better. The Zorki was never intended to be “as good” as a Leica because they were always meant to be cheaper cameras. If you look at any industry where one company copies the product of another, there are always going to be differences in quality, corners cut, or lesser materials used.

It wouldn’t make sense for the maker of counterfeit Rolexes or Coach Hand Bags to make a product with the exact same materials and build quality as the original as it would likely cost the same. The whole idea of making a copy is so you can offer it at a discount to the real thing, to compel people to buy it. The same thing applies to the Zorki. Whether the engineers and assembly line workers at the KMZ plant where the camera was made could have built something to the exact same specifications as the Leica is unclear, but they didn’t have to.

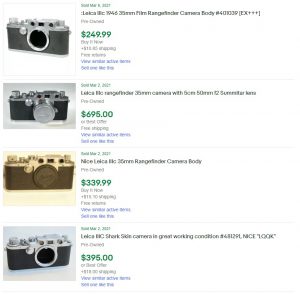

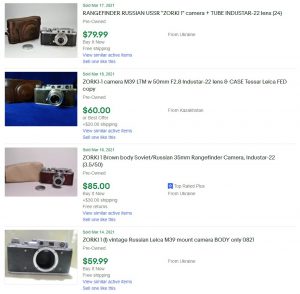

Zorkis were always meant to cost less than Leicas. That is a fact back in the 1940s and 50s when these cameras were new, and it still holds up today. Looking at used prices of a Leica II or III, $150 seems to be the going rate for a tattered body, with nicer examples including a lens going for $250 and up. Likewise, Zorkis with collapsible Industars can be had easily from $50 – $75.

As fort the value, simply having a cheaper product that doesn’t come close to comparing to the more expensive option isn’t a good value, but that’s not the case with the Zorkis I’ve held. Sure, they don’t have as consistent of engravings, yeah, the film advance can sometimes be a little rougher, and there are definitely some cosmetic differences, but none of these take away from the shooting experience or the images the cameras are capable of making. For what little you lose, compared to how much cheaper they are, the Zorki is the clear value winner.

The End Result

I think you already know where I am going with this. Putting aside the user experience, how much effort went into building something, or how much it cost, cameras are meant to make pictures. Once the photograph is made, how many people really care what shot it? You either like the image or you don’t, and for that I’d say both Leicas and their copies do a great job of that.

Excluding cameras with operational faults, in my opinion, you can get just as nice of images from a Zorki as you can a Leica. Even if some pixel peeping vintage lens blogger were to take the Industars and Summitars often found on these cameras and mounted them to a 100 megapixel digital camera and looked at lens resolution charts blown up to 1:1 on a professionally calibrated 8K gaming monitor, maybe then you might see some optical differences between the lenses, but that’s not what I do. I’m just a guy who likes to use old cameras and take photos. For that, both do their jobs incredibly well.

My Results

For my first roll through the Zorki, I chose Kodak ProImage 100. I felt that the lens coating of the Industar-22 would be a good candidate for color film, and without any suitable Soviet era color film in my film drawer, I picked the ProImage as it works really well with the shutter set to 1/100 and using Sunny 16. With the lens collapsed, the Zorki is very compact, so I kept it with me as I went about my daily business, shooting photographs of random thing I encountered.

As it turned out, I failed to extend the lens fully throughout a majority of the roll, resulting in a large number of out of focus images. Learning from my previous mistake, I loaded in a second roll of slightly expired Rollei RPX 25 and remembered the keep the lens fully extended.

Hopefully anyone reading this article has been to my site enough times to know that I am not irrationally loyal to any one brand, nationality, format, or style of camera. I review everything from 1980s point and shoots, to wooden box cameras, to the most expensive 35mm panoramic camera. I review Soviet cameras, Japanese cameras, Czech cameras, and French cameras. If it could shoot a picture, and I can reasonably get ahold of it, I will review it.

That said, I am neither a Soviet camera fanboy, nor do I hate Leica. My overall positive vibe for the Zorki in this review is because the camera deserves it.

For something that today costs anywhere from one-fourth to one-tenth of something else, yet works the same way, has the same chance at conditional issues, and produces images with nearly the same image quality, calling the Zorki an adequate alternative to the Leica is a no brainer for me.

From the moment I first picked up this Zorki, even after loading film into it, shooting, and looking at the images I got from it, I have been impressed with this camera. Maybe that has something to do with my expectations because I really didn’t know what to expect, but I would be willing to bet, my experience would be similar to the overwhelming majority of people out there want a Leica-like experience, without the Leica-like price.

If somehow, my word isn’t good enough, take it from Johnny Martyr, a Frederick, Maryland based professional photographer who uses his screw mount Leicas to shoot weddings and other paid events, when he compared this exact camera to his own, and upon listing off a variety of nit-picks about the Zorki, admitted:

To be completely fair, the negatives I’m pointing out here are mere comforts of use and evidence of possible longevity/durability under use, not complete hindrances to quality photography to those who are talented and motivated.

Johnny bought into the value proposition saying that although he firmly believes that the Leica is a superior camera and he would have no desire to ever buy his own Zorki, he concluded that:

A Zorki-1c could be a great purchase to help decide if one wants to invest in an early Leica…for the small cost of between $40-$150, it may be as close to “there” as it needs to be!

Looking at the images in the gallery above, I can’t see anything that stands out to me good or bad compared to other mid 20th century 35mm cameras. Sharpness is excellent in the center, and tapers off slightly near the corners, but nothing that makes a dramatic negative impact on the images. In the case of the color shots, the blueish-purple lens coating of the Industar rendered them faithfully, especially the ones of the fish pond and garden wall images which were taken in full shade. The black and white images came out a bit soft, but that had more to do with the film than the lens, but otherwise look great.

If you are in the market for a Leica, buy a Leica. They’re historically significant cameras that are built to last a lifetime and will likely retain their value or perhaps even go up in the years to come. If however, you are not interested in competing with a world full of Leica collectors and spending premium prices on a camera, and just want to know what shooting a Leica is like on a budget, then by all means, check out a camera like the Zorki. As is always the case, you need to make sure you get one that is in confirmed working order, as any camera whether it was made in Germany, Japan, or the Soviet Union will suffer the rigors of time equally.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zorki_1

http://sovietcams.com/index7584.html

https://kosmofoto.com/2020/04/zorki-1-the-red-zed/

https://johnnymartyr.wordpress.com/2020/04/07/martyrs-leicas-vs-eckmans-copies-zorki-1/

https://www.filmphotography.at/zorki-1-soviet-film-camera-review

“I’m just a guy who likes to use old cameras and take photos.” AMEN, brother! Thanks for a very detailed review.

I think that sentence applies to me as the collectors can accuse me of not being a real collector, and the photographers can accuse me of not being a real photographer! 🙂

Another great article, as usual, Mike.

I have a few “Barnack” copies, Nicca, Tanack, Leotax, Fed 1 and, of course the Zorki 1c, the subject of your article. I’m fully in agreement with you. These cameras were never intended to compete with Leica, there wouldn’t be any point, but they do permit an element of the Barnack experience with a much lower price entry point. And especially with the mass production of the Soviets they were very much peoples’ cameras. The Leica was, and still is, an elitist camera. Nothing wrong with this per se, but their prices are an entry block for many.

So enter all the copies to satisfy the masses, and they all do a fairly good job, too.

A problem today for many of these copies, is their low price. Given this, people are likely to begrudge a service, whereas if you own a valuable Leica a service makes far more sense. So I suspect many of these copies aren’t functioning as well as they once did new.

My Zorki 1c had a full service and cla before I got it, and this was reflected in its price, but it is a joy to hold, and with brilliantly clear v/f and r/f makes it an eminently usable little camera. My sole reservation is the period lens, an Industar 22. Tests on my digital cameras show it to be quite a poor performer until reasonably stopped down to f8, but even then the edges are always behind at all apertures. Now contrast this with one of the accepted better, but later lenses, the Industar-61, it is like chalk and cheese. This is an excellent f2.8 lens and unless originality was needed, I’d use this on any of my Soviet r/f L39 cameras, and yes, even prefer it over the f2 Jupiter, which I’ve found slightly behind the 61 at all apertures.

“In fact, in Johnny’s comparison of my Zorki vs his Leicas, he noted that the rangefinder patch and viewfinder of my Zorki held up better than any of his Leicas”

No, that is not what I said! 🙂 Your Zorki’s finder patch is very clear and contrasty unlike my IIIc which needs a new beam splitter. I did not say anything about the Zorki vs my 1930 or IIIf which are probably about on par.

I fixed it, to accurately reflect what you said! 🙂

I really like your “bipartisanship” here, Mike and you make a good point in saying

“It wouldn’t make sense for the maker of counterfeit Rolexes or Coach Hand Bags to make a product with the exact same materials and build quality as the original as it would likely cost the same. The whole idea of making a copy is so you can offer it at a discount to the real thing, to compel people to buy it.”

Thanks for returning to some of my thoughts and giving your side of things. I think we’ve painted a pretty accurate picture of this age-old question 😉

I appreciate your feedback, and definitely don’t regret sending you those three cameras last year. Not only did it help me with this review, but reading your thoughts was infinitely fascinating to me!

Mike, I liked this article very much. You are dead nutz right. Copies are there for a reason, I have repaired cameras for close to 45 years…I have no reserve as to which is better..they all can take good to great pictures. In the wrong hands a $8000.00 Canon will not change that! It’s that deep desire and more importantly the feel of the camera in your hands….that there bud, changes the game a whole lot. If it feels good, then you will use it, know where button and dials are on that job. And confidence in using it. Yes it takes time, but then when you are one with said camera, you can just concentrate on composing your subject to get a better shot. I personally do like the leica, but also like any of the Oskar Barnack designs. Not to brag…but have a few leicas, zorkis, feds, Nikons, Canons, ect….asorted lenses. But I always come back to my zorki2 with self timer…its a kiev version. These are very hard to find only 10380 or so were made. And a fed 50mm collapsible lens..love it..I don’t know why. But I bet it’s that feel about it. Just like the leica iiif.

To any of you that have read this far….you can’t go wrong with any of these old film cameras….go get a good one, grab some film…go out and shoot…btw. developing your own film is very easy…if u shoot black and white, it’s even easier than ever..one chemical and water…done! Thanks again Mike great article! ^_^

Thanks for the feedback Mike. I agree, I’ve had really good luck with my Soviet Leica copies. Even in the cases where they’re not as smooth, they still perform the same job of making a photograph quite well. I find the Industar-22 and -50 to compare very well to the Leitz Elmar 3.5.

Too many reviews of old Russian cameras are based on poorly functioning examples and then those faults get added to the list of reasons why Russian cameras are rubbish. I’ve got several Zorkis, and as they are all well over 50 years old I’ve had them serviced by a wonderful guy in London, he cleans, lubricates, and adjusts them to work smoothly and accurately. These are the cameras people should test and review, not the gummed up example that’s been sat in grandad’s cupboard since 1972.

I agree, many Soviet cameras were used hard. These were not collectors items back then and some of the negative opinions on these cameras are formed with less than ideal specimens. Thankfully, the Zorki I used in this review was, and continues to be in perfect operating condition!