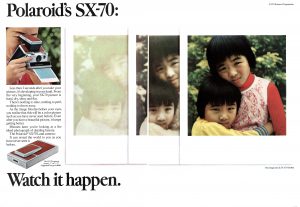

This is the Polaroid SX-70 an instant film camera produced by Polaroid between the years of 1972 and 1981. The SX-70 was a landmark camera as it was the first instant camera in the world to use pack film, instead of the more common roll film as all previous Polaroids used. Each pack of film for the SX-70 had ten sheets that each contained the necessary chemicals to develop an image. After the exposure was made, the camera would automatically eject the image through metal rollers that would squeeze the development chemicals, spreading them over the photographic image, allowing them to develop outside of the camera. The SX-70 had automatic exposure and was a true SLR in that the image seen through the viewfinder was what would be captured on film. Variations of the original SX-70 would be released until the 1980s when the folding models were replaced by solid bodied ones.

This is the Polaroid SX-70 an instant film camera produced by Polaroid between the years of 1972 and 1981. The SX-70 was a landmark camera as it was the first instant camera in the world to use pack film, instead of the more common roll film as all previous Polaroids used. Each pack of film for the SX-70 had ten sheets that each contained the necessary chemicals to develop an image. After the exposure was made, the camera would automatically eject the image through metal rollers that would squeeze the development chemicals, spreading them over the photographic image, allowing them to develop outside of the camera. The SX-70 had automatic exposure and was a true SLR in that the image seen through the viewfinder was what would be captured on film. Variations of the original SX-70 would be released until the 1980s when the folding models were replaced by solid bodied ones.

Film Type: Polaroid SX-70 Instant Pack Film (originally 10 exposures per pack, 8 today)

Film Type: Polaroid SX-70 Instant Pack Film (originally 10 exposures per pack, 8 today)

Lens: 116mm f/8 Polaroid coated 4-elements

Focus: 10.4 inches to Infinity

Viewfinder: Folding SLR Mirror

Shutter: Electronic

Speeds: 10 seconds to 1/175

Exposure Meter: CdS exposure meter with full Programmed Automatic Exposure

Battery: 6v “Polapulse” Zinc-Chloride Integrated Cell in each film pack

Flash Mount: SX-70 Accessory Port

Weight: 756 grams (with film)

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/polaroid_pdf/polaroid_sx-70_alpha_1.pdf

Manual (Quick Start): https://www.cameramanuals.org/polaroid_pdf/polaroid_sx-70_quick_view.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Polaroid SX-70 is a historically significant camera that is one of the most distinctive looking and attractive cameras ever made. No other company even came close to making something that looked or functioned like the SX-70. It single handedly launched the concept of integrated instant film and permanently linked the name Polaroid with that of instant film. The camera is gorgeous to look at and very simple to use. The biggest challenge with the SX-70 is that Polaroid’s original film has not been made in nearly two decades, and the film that is currently available is nowhere near as good or practical to use today. The SX-70 is a camera worthy of being in any collection, and will likely strike up a conversation to anyone who sees you use it, but you’ll need to keep your expectations low of the results it will give. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for extreme historical significance, one of the most technologically impressive and pioneering cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.4 | ||||||

History

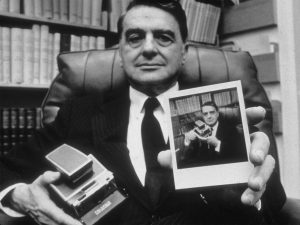

The Polaroid SX-70 wasn’t the first Polaroid camera, but it might have been the most important. The story of this camera starts the same every Polaroid that came with it, with a man named Dr. Edwin Land.

Wikipedia suggests Dr. Land was the Steve Jobs of the mid 20th century due to his visionary ideas and groundbreaking patents. Simply calling him a visionary or an inventor doesn’t do his story justice, as a visionary only needs to see something. An inventor only has to create something. Dr. Edwin Land was both, he had a vision for a camera that developed it’s film instantly, he invented a way to do it, and he engineered and marketed it into one of the most successful companies of the 20th century.

Dr. Land once studied chemistry at Harvard University before dropping out of school after his freshman year to pursue development of polarizing light filters. Together with his Harvard physics instructor, George Wheelwright, they both formed the Land-Wheelright Laboratories in 1932. The company would later be renamed the Polaroid Corporation in 1937.

Polaroid’s original patents were for a light polarizing film called ‘Polaroid film’, which was used in the manufacturing of glare reducing sunglasses, 3D projection, and during WWII, night vision devices. In total, Dr. Land is credited with 533 US patents, which is second highest by any one person, only to Thomas Edison.

Polaroid was already quite successful by the end of World War II, but it wouldn’t be until 1948 that the company would release it’s most game changing product, the instant film camera. Like Kodak, Polaroid was a “film first” company and only made cameras as vessels to consume film. Polaroid’s instant film required a camera to use it, and as a result, the Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 was born. There is a rumor that the number “95” was chosen because that was the price the camera was said to sell for, but period advertisements show the camera often selling for right around $100, so I am not sure if that’s just a rumor of convenience, or if there is some truth to it.

Polaroid would outsource construction of the earliest Model 95s to other US companies like Wollensak, Bell & Howell, Samson United of Rochester, NY, and possibly even the Timex Corporation out of Atlanta, GA. The Model 95 used a new type of Polaroid instant film that would sandwich light sensitive negative and positive layers between a reagent chemical that when exposed to light, would transfer and develop an image from the negative to the positive side. The positive side would be removed from the camera and would serve as the photograph. The total time to develop an image was right around 1 minute, but would vary depending on outside temperature and film stock used.

Over the next several decades, Polaroid would release a huge number of different models, first using the same instant roll film used by the Model 95, and later “peel apart” pack film that allowed the photo to developed sandwiched between an emulsion and development layer.

By the between of the 1970s, Polaroid cameras came in a huge variety of shapes and sizes and models were available at a variety of price points, but the world of photography was very different from the one that existed when the first Polaroid was created. The demands of smaller and easier to use cameras with features like automatic exposure and reflex viewfinders were coming at the company from all directions, and Edwin Land knew that he needed to come up with something different.

In a Polaroid company meeting in April 1972, Edwin Land walked up on stage and pulled an SX-70 out of one of his suit pockets and in the next ten seconds took a sequence of 5 photos, showing them to the audience after they developed. With each new exposure that came out of the camera, the audience was stunned as all previous Polaroid cameras required the user to either tear the ejected photo from the rest of the roll or in some other way manually manipulate the photo to finish the exposure. With the SX-70, everything was self-enclosed a single sheet with nothing more needing to be done after the exposure was made, other than wait a little bit.

In the short one page preview in the July 1972 issue of Modern Photography, the debut of the SX-70 is told in greater detail, explaining how Land smoked a pipe on stage as he shot his sequence of shots. Later demonstrations of the camera were shown to the audience with each exposure receiving a hole punch through the image to identify it and promptly stored under lock and key in a presentation case so that no samples could leave the area.

In that initial announcement, only color film was shown or mentioned for sale, with promises of a large supply of film to be available when the cameras would eventually go on sale at a list price of between $100 and $150.

As the photographic press caught wind of the new camera, people’s mind’s raced with curiosity and wonder. It almost sounded too good to be true. The all in one sheet film by itself was amazing by itself, but adding to that the camera itself with fully programmed auto exposure and a through the lens reflex viewfinder in a collapsible body that when folded shut was no larger than a small hard cover book.

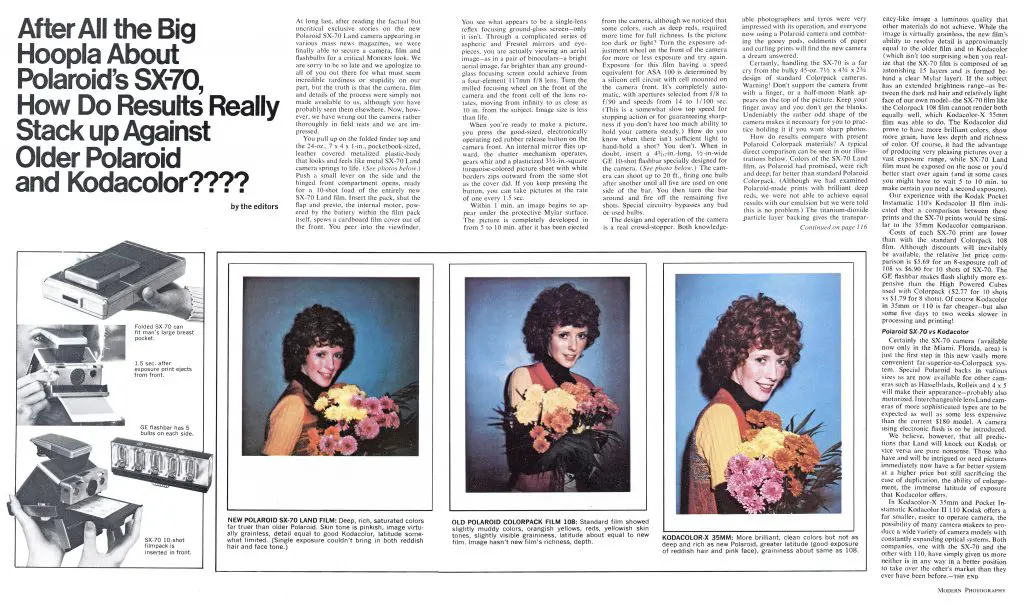

The first published look at the SX-70 that I could find was published in the January 1973 issue of Modern Photography. Credited as being simply by “the editors” the article does a short comparison between Polaroid’s older Colorpack film and Kodacolor-X 35mm film.

The short preview starts out by stating that acquiring testing samples of not only the film, but also the camera were very difficult, even for a major publication like Modern, suggesting a tremendous amount of hoopla that likely surrounded it’s release. The rest of the test gives a quick overview of the camera’s use along with some impressions of the film itself, including it’s price, which at the time was $6.90 for a pack of 10 exposures. When adjusted for inflation, this compares to just under $43 today, a far cry from the current retail prices of Polaroid Originals SX-70 film.

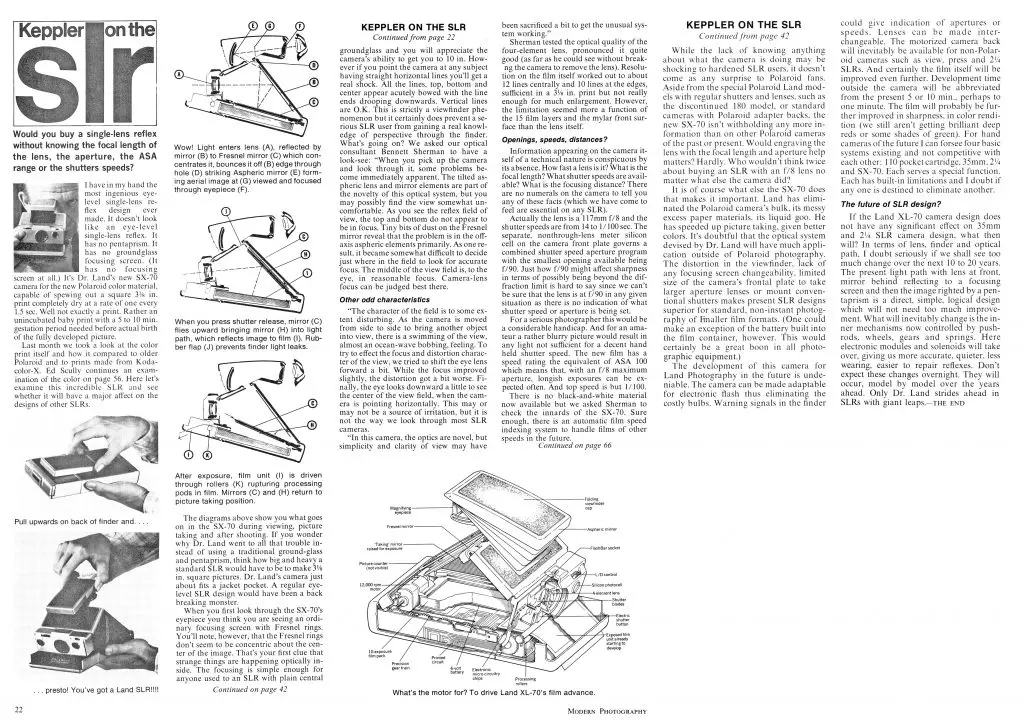

For someone looking for more technical information on how the camera works, they only needed to wait one month as in February 1973, Herbert Keppler published his behind the scenes look at the SX-70 and how it worked.

Keppler, as he always did, gives a thorough explanation to how the SX-70s unique SLR viewfinder works. Traditional SLRs typically used a solid piece of glass known as a pentaprism and some kind of textured ground glass to achieve through the lens composition, but the SX-70’s folding design had neither of those things, instead using a clever arrangement of three different mirrors and a glass eyepiece that when opened give a true representation of what will be captured on film.

Keppler’s comment on the resolution of the lens is inconclusive saying that the images produced by the camera looked good, but an accurate test was hampered by 15 layers of film and the protective Mylar window covering each exposure.

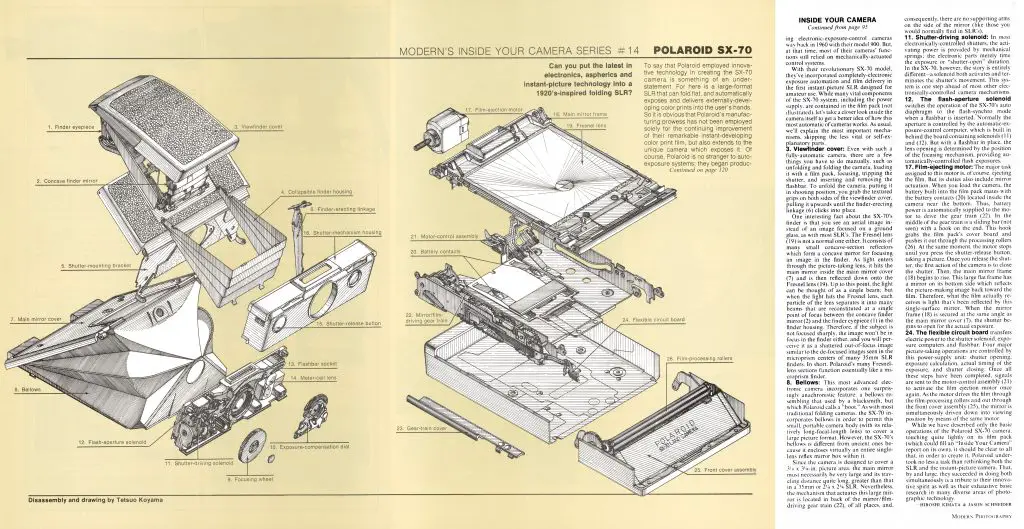

In a second “inside look” from October 1975, Modern Photography once again gave a glimpse of the inside of the SX-70 with detailed info on how the camera works.

In one final article, this time from the January 1973 issue of Popular Science, the SX-70 is looked at from a more technical perspective, rather than that from a photographic magazine. A great deal of information regarding the camera’s inner workings was given, including some information on the construction of the body and the camera’s zinc-chloride “Polapulse” battery which was contained in each film pack, rather than the camera itself, a decision that not only impacted prices of film but also drove environmentalists crazy! Despite looking like having an all metal body, the Polaroid SX-70 has a precision molded polysulfone plastic body with a metal alloy coating consisting of chrome, nickel, and copper that gives it a distinct brushed metal appearance.

Initial shipments of the SX-70 were sold in late 1972 with the camera not available nationwide until later in 1973 but once it was on sale, it was a tremendous success. A combination of convenience of the new film along with the wonder of how the camera worked kept it a best seller for quite a number of years.

The SX-70 would see several changes throughout it’s life but would maintain the same basic shape, lens, and film system. The earliest SX-70s have a matte focusing screen without any focus aides, but later versions added a split image focus aide.

In 1974 and 75, the Polaroid SX-70 Models 2 and 3 were released which ditched the metal plating, instead coming in a white plastic and darker brown leather covering on the Model 2, and a black plastic and dark brown leather body. The Model 3 also eliminated the SLR viewfinder, replacing it with a simpler non-TTL optical viewfinder. In 1977, a new model called the SX-70 Alpha 1 was released with the original’s metal alloy and tan body covering, but adding a tripod socket and strap lugs. A few models branded for Sears and Foto-Quelle retailers were also available with subtle cosmetic changes as well.

Perhaps the most significant update to the SX-70 came in 1978 with the release of the SX-70 Sonar OneStep and SX-70 Sonar AutoFocus. Featuring a metal and black body with a large rectangular auto focus unit affixed above the front plate, the SX-70 Sonar OneStep added fully automatic focus to the otherwise manual focus SX-70. This was not only notable as being the first auto focus Polaroid camera, but also the first ever auto focus SLR of any kind!

As the name implies, the Sonar model uses an electronic SOund NAvigation and Ranging (or SONAR for short) unit to detect distance using sound waves instead of light. This had the distinct advantage over other light based auto focus technologies as it could work in complete darkness. Using a flash mounted to the camera’s optional flash port, the SX-70 Sonar OneStep could accurately focus and meter for an image in a completely dark room, something that current day auto focus technologies can’t do without some sort of supplementary light assist.

The original SX-70 would remain in production until 1981, but would be replaced by rigid, non folding cameras using the same SX-70 film. One such camera was the Polaroid Land Camera Supercolor 1000 that had a much simpler design and lens, allowing it to be sold for considerably cheaper than the original camera.

By the 1980s, SX-70 cameras and film would be replaced by very similar, but much faster Polaroid 600 cameras and film (ASA 600 vs 150). Using an identical size film and magazine, Polaroid 600 film can be used in SX-70 cameras with a neutral density filter placed over the lens to prevent the faster film from over exposing in the older camera. Both SX-70 and 600 film would continue to be produced until around 2005, at which time, demand for the film had been replaced by the rise of digital photography.

Dr. Edwin Land would run his company until his retirement in 1981 and although the Polaroid Corporation would live on in his absence, the company’s pioneering days of innovation would be over. Polaroid would stumble into the 21st century and would not survive the arrival of digital photography. In 2001, the original Polaroid Corporation would file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and although a Polaroid holding corporation would continue to operate and make Polaroid film, the new company would cease all film manufacturing in 2009 relegating the Polaroid brand to a marketing name applied to various products made by other companies.

Today, very few Polaroid cameras are sought after by collectors. A combination of a difficulty in using these cameras today, plus a huge number of uninspired and cheap plastic models, prevent most Polaroid cameras from being desirable.

The SX-70 and it’s variants are a notable exception as these cameras in good working condition can still fetch well over $100 as the overall design and looks of the camera stand apart from the cheap plastic models that would follow. A combination of historical importance, a distinct design, and a whole bunch of nostalgia make the SX-70 an excellent camera to add to your collection.

My Thoughts

I’ve had the fortune of being able to own and review many of the most significant cameras of the 20th century. The Kodak No.2 Brownie, Leica rangefinder, Argus C3, and Nikon F are just some.

Adding to that list is the Polaroid SX-70. It wasn’t the first instant camera, but the SX-70 introduced the world to all-in-one pack film. All prior instant film cameras used a type of roll film that needed to be manually pulled out of the camera and separated from it’s backing paper as the image developed. With the SX-70, you just point your camera at something, pressed the shutter release, and an image would appear.

When designing the camera that would become the SX-70, Dr. Edwin Land didn’t just create an innovative new film, he also created an innovative camera with a design never before seen. In it’s folded position, if you had never seen an SX-70 before, you would be forgiven for not realizing it was a camera at all. With it’s tan leather body covering and brushed stainless body, the camera measures 7 inches by 4 inches wide, and less than 2 inches tall when folded.

It’s not until you open the camera to where you’ll start to get the hint that this is a camera. This is accomplished by gripping the sides of the viewfinder lid on the top of the camera and pulling straight up.

With the camera open, the side takes on a triangle shape with rubber bellows helping to maintain a light tight film compartment. The bellows are shaped like those found on fireplace stokers.

From behind, you get a good look at the folding rear eyepiece that peers down into the camera’s viewfinder. It is not until you actually put your eye up to the viewfinder do you realize that the SX-70 is an SLR. You see through the taking lens, allowing you to exactly see what will be captured on film.

The design of the viewfinder uses a clever arrangement of mirrors and lenses instead of a glass prism like with most SLRs, so the image you see has some optical aberrations around the edges, similar to that of a porro viewfinder like in a set of binoculars. You must take care to perfectly center your eye in the viewfinder in order to see the full frame, otherwise the edges of the image will disappear.

The viewfinder image on most SX-70s has a split image focusing aide, much like many 35mm SLRs of the 70s and 80s. The earliest SX-70s lack the split image however, only having a ground glass focusing screen.

The SX-70 is a fully automatic camera and does not have direct control over shutter speeds or f/stops. Your only method for exposure is a half black/half white wheel on the front of the camera, to the right of the lens. This functions similarly to a +/- EV dial found on many automatic cameras. Unlike those cameras however, there are no indicated exposure numbers, simply unmarked hashes.

Opposite of this dial is a black wheel that controls focus, which is also unmarked. Later cameras in the SX-70 family would have focus distances marked around the lens, but not this one. There is no way to focus this camera without looking through the viewfinder, and there is no depth of field scale anywhere on it. Finally, beneath the focus wheel is the prominent red shutter release button.

The Polaroid SX-70 requires film specifically made for it. Although Polaroid 600 film is very similar and can be used, it is a different speed and will greatly throw off the exposure. Loading a new film magazine into the camera requires pressing down a little button with a yellow sticker, seen on the camera’s right side. Pressing this button will release a latch which allows the front of the camera to drop down, revealing the film compartment.

The film compartment is a rectangular hollow space, which you insert or remove a full or empty film pack. When it was time to remove an empty pack, a small paper tag on the front edge was used to easily pull it from the camera for disposal.

Each time you insert a new film magazine, you are also replacing the camera’s battery as the camera’s power comes from a 6 volt wafer-thin battery pack inside each magazine. To power the camera for a total of 10 exposures in original Polaroid film packs (current Polaroid Originals packs only have 8 exposures), the battery needed to be able to power the camera for sixteen times that amount to account for power drain as the camera sits in between shots.

When new, all Polaroid film packs have a piece of cardboard called a dark slide, that protects the light sensitive sheets of film from light as it is inserted into the camera. Immediately after inserting a new film pack into the camera, the dark slide would be ejected through the film slot on the bottom edge of the camera, readying it for use. In the event someone wanted to remove a partially used film pack from the camera, the dark slide can be carefully inserted back into the film pack in a dark room, so that it can be reused at a later time.

Another use for the dark slide is for protecting images from direct sunlight as they come out of the camera. The current types of SX-70 film are more sensitive to bright light during development which can alter the exposure of an image as it is ejecting from the camera. Polaroid Originals makes a “tongue” that you can buy and stick to the bottom of some Polaroid cameras that helps shield the freshly ejected image from light, but what I do is take the dark slide and use a piece of tape to secure it to the front edge of the camera so that as each image comes out, the dark slide is shielding it.

With a new magazine of film in your camera, all that’s left to use it is to take it out, point it at something and start shooting. The back edge of the camera has a small square window with an exposure counter that shows the total exposures remaining. When using the type of SX-70 film that was originally made for it, each magazine had 10 exposures, but currently available SX-70 film only has 8 so once it reaches ‘2’, there won’t be any more shots. Keep this in mind when shooting your camera as you’ll get two less exposures than the exposure counter suggests.

The novelty of instant film is there today with sales of Fuji’s Instax film still very strong. When the SX-70 first debut in 1972, people were amazed at the speed and ease the camera operated. Nearly 60 years have passed since Edwin Land debuted the first model, but time has done little to slow the camera’s appeal. With a good working SX-70, a couple packs of fresh Polaroid Originals film, all that’s left is to load up the camera and take it out shooting.

My Results

I started this review back in the summer of 2019 when I picked up some Polaroid Impossible SX-70 film and shot random photos around my house. With those packs of film, I quickly learned one of the most important lessons about instant film, which is expiration dates matter.

With traditional negative and positive film, expiration dates are more like suggestions rather than ultimatums. Most color films can be shot years after their expiration dates with the only negative affect being color shifts which can often be minimized in post processing. Black and white films usually last much longer, sometimes being completely usable decades after their expiration dates. A little extra exposure is generally all that’s needed to get a good image from a 30 year old expired roll of Kodak Tri-X.

With instant film, the light sensitive emulsion works similarly to that of non-instant film, and probably could survive years or decades, but the developing chemicals within the film that actually make the image appear do not. When instant film expires, the chemicals lose their ability to develop an image, and in some cases, harden into a paste-like substance, unable to be evenly spread across the light sensitive image. So while the light sensitive film might still be good, you’ll never get to see it.

Discouraged by what turned out to be pack after pack of poor images, plus the high cost of new SX-70 film, I shelved the camera until this past winter, when I decided to give it one more go, this time with the freshest Polaroid Originals color and black and white film I could get my hands on. I should point out, that before a word of this review was even written, I had spent more than 4 times more on film than I ever did on the camera itself.

I’m going to cut right to the chase and say the obvious, which is that although I admire the challenge the new Polaroid Originals (formerly Impossible) company has taken on in reverse engineering the SX-70s integrated film that the original Polaroid discontinued in 2009, the current stuff, still does not hold a candle to the original film.

The images above represent the very best examples of what I was able to get from both fresh Polaroid Originals film with an expiration date of 12/2021 and a few mildly expired Impossible rolls. The fresh film definitely performed better, but to suggest that these images look “good” is highly subjective. For this review, I used two different SX-70s, the original tan and chrome model seen throughout this review, and a second SX-70 Sonnar, and despite both cameras working correctly, every image came out soft, with heavy color casts. From the same pack of film, I shot the selfie of myself in the mirror and the railroad crossing pictures. The selfie has a very strong yellow cast, while the outdoor shots were very blue, with muted colors.

I also noticed that leaving the camera’s exposure dial in the center badly over exposed all of the images. I had to turn it the first large hashmark towards the black side before I could get these images with decent exposure. This occurred using both fresh color and black and white Polaroid Originals film. I am unsure if the metering circuit on my cameras is just off, or if this is normal for the current film.

Further adding to my dismay of looking at these images is knowing the cost per shot is higher than any other camera I’ve ever reviewed. For two packs of film direct from Polaroid Originals, I used a 10% off coupon they offered me, but with tax and shipping, my total was $40.96 for 16 images. At a cost of over $2.50 per image, it can be a tough pill to swallow when you see less than ideal images. Now I know, as soon as I complain about a $2.50+ per shot cost, someone is going to point out that it’s much more expensive to shoot 8×10 glass plates or some other kind of obscure camera, but I would be willing to bet those 8×10 glass plates look a lot better than these images do.

I can’t even begin to comment on the quality of the 4-element 116mm f/8 Polaroid glass lens, as the film does not resolve enough detail for me to make any meaningful conclusions. I wonder if anyone has ever taken apart an SX-70 to remove it’s lens and adapt it to digital to see what this lens is really capable of, but it being a 4-element design, I would guess it is pretty decent.

Complaints aside about the less than ideal quality of modern Polaroid Originals film, and the high cost per exposure, I should probably back myself off the ledge and say that shooting an SX-70 isn’t really about the image quality and more about the experience and novelty. Ever since Edwin Land released the first Polaroid camera in 1947, there has been a mystique about instant film cameras.

Today, Fujifilm makes more money from Instax cameras and film than any other photographic product they make. While the immediate gratification of digital photography has eliminated the waiting period of the film era, to have a tangible print of a photo in your hands that you can see and feel is just as cool in 2021 as it was over half a century ago.

The Polaroid SX-70 was then, and still is a technological marvel. It has a look, a feel, and a sound unlike any other type of camera ever made. To someone whose never seen one before, the simple act of pulling up on the viewfinder hood to open the camera is enough to amaze most people, but once you see your photo coming out of the bottom, it’s like magic!

I still think there is merit for owning and shooting an SX-70, and I am extremely grateful that the folks at Polaroid Originals are doing their part to keep these cameras working. I hope they continue to find ways to make the images look nicer, and maybe someday go back to offering 10 exposures per pack instead of 8, but for now, the current solutions will do.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Polaroid_SX-70

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polaroid_SX-70

https://emulsive.org/reviews/film-reviews/polaroid-originals-sx70-film-review-and-user-guide

https://www.photothinking.com/2019-03-16-polaroid-sx-70-instant-engineering/

https://danfinnen.com/review/polaroid-sx-70-sonar-land-camera-review/

You wrote that: “The SX-70 was a landmark camera as it was the first instant camera in the world to use pack film, instead of the more common roll film as all previous Polaroids used.”

I beg to differ on that statement. I remember the Polaroid 100-series cameras that took Type 100 and later, 660-series pack film in the early 1960’s. These would range from the Polaroid 100 to the completely manual 180 and 195 models beloved by “let’s check the exposure before using sheet or 120 roll film,” professional photographers. These was the “peel-apart” Polaroid pack film system that succeeded Polaroid roll film.

The SX-70 was the first “non-peel-apart Polaroid pack instant film that developed in daylight before your eyes.”

You’re right, I kinda skipped peel apart film. Nevertheless, the SX-70’s new film packs were much different than anything that came before it!

I’m very glad that any film is available-and I find he eventual result of the new stuff quite acceptable.Amazing that it even exists! Most of what I shot back then had a yellow cast, too and wasn’t very sharp. I vastly preferred packfilm. The SX 70 is a fantastic device and it’s party trick never gets old. I hope the developing speed gets faster. (I’ve heard the new stuff lacks the archival properties of the old, that apparently rivals Kodachrome)

There certainly are a lot of compromises with the new film, but like you said, the fact that it even exists at all is cool. I am really glad I was able to shoot this camera and make these images, but it’s just not very practical to use regularly.

Polaroid also sold their SONAR module components industrially. They sold an experimenter’s kit with a sensor and I think one circuit board so you could try it out and perhaps use it in some ranging application. Where I worked at the time, we got one and it worked quite well. Such things were familiar to us because one of our products measured water level with an ultrasonic sensor. Polaroid’s was vastly less expensive.

But, alas, not waterproof. One thing I think might prove true about all those polaroid photos is that, over time, a larger percentage will survive than digital photos because people don’t protect their digital data very well.