This is a Sony CyberShot DSC-F828, a premium digital bridge camera made by Sony starting in 2003. The DSC-F828 was the last in the Sony CyberShot F-series made between 1999 and 2004 which added a bunch of premium features sourced from Sony’s extensive lineup of camcorders which at the time Sony was a leader in building. The DSC-F828 has a premium Carl Zeiss Vario-Sonnar 7x zoom lens with a maximum aperture of f/2 that has a 100 degree tilt range up and down, an 8 megapixel 4-color RBGE color CCD sensor, and supported a huge number of auto exposure, auto focus, and various other shooting modes. One of the more interesting features of the DSC-F828 was it’s “Night Shot” mode which helped it focus and expose in complete darkness, something other cameras then and even now cannot do. Although it wasn’t designed this way, this night mode can be exploited to take infra-red images in daylight without any modifications to the camera.

Sensor Type: 8 Megapixels 2/3″ CCD four color RBGE (E = Emerald) sensor

Storage: Sony Memory Stick/Memory Stick Pro and CompactFlash Type I/II

File System: SRF (RAW) + JPG, JPG, TIFF

Lens: 7.1mm to 51mm (28mm to 200mm equivalent, 7x Zoom) f/2 – f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Vario-Sonnar T* coated 12-elements in 9-groups

Focus: Macro Focus 2 cm to 50 cm, Regular Focus 50 cm to Infinity, 5-point Multi, Center, and Spot Focus modes, Manual Focus

Viewfinder: 235k pixel 0.44″ TFT LCD Electronic Viewfinder, 134k pixel 1.8″ TFT Rear LCD

Shutter: Programmed Electronic Shutter

Speeds (Programmed AE): 1 – 1/3200 seconds, step less

Speeds (Manual): 30 – 1/2000 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL Multi-Pattern Auto Exposure with Programmed, Av, Sv, and Manual Modes

Sensitivity: ISO 64 – 800 equivalent

Battery: 7.2v Sony NP-FM50 Lithium-Ion Battery Pack

Flash Mount: In-body Pop-Up Flash with TTL flash metering, red-eye, and slow-sync modes

Weight: 930 grams (w/ battery)

Manual: https://www.sony.com/electronics/support/compact-cameras-dsc-f-series/dsc-f828/manuals

How these ratings work |

When it was released, the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 was top of the line bridge camera featuring a state of the art Zeiss lens and a very long list of features. It had one of the highest megapixel sensors of it’s generation and produced images that are still comparable with modern digital cameras in 2021. Of all the reasons to consider the DSC-F828, it’s most unique feature are it’s Night Shot and Night Framing features which use a hinged visual light filter that can be moved out of the way to turn the camera into a full spectrum digital camera that when used with an IR filter allows for infrared digital photos. An additional feature of the camera is one Sony likely never intended, which is to place a magnet on a specific part of the camera to manually deactivate the feature, making the DSC-F828 one of the few digital cameras ever made that can shoot IR and back to normal without any internal modification of the camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for unique feature set and state of the art features that are still relevant today | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

Sony is one of the biggest technology companies on the planet. With an endless lineup of successful TVs and radios, to the Walkman, the PlayStation videogame console, and a huge line up of digital cameras made over the past 30 years, there is not much that Sony hasn’t done successfully.

This review is for the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 from 2003, which is a very cool camera with an excellent lens and a ton of features, but the reason it’s being reviewed here is for an interesting feature that very few digital cameras have, and one that can be easily exploited to do something that no digital camera ever could (at least not from the factory). I’ll get to that later, but first, a quick history about Sony.

Originally founded on May 7, 1946 as Tōkyō Tsūshin Kōgyō, or Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation, by Japanese electronics industrialists Masaru Ibuka and Akio Morita, Sony’s early products were primarily in the audio recording market. Their first product was a reel to reel tape recorder called the G-Type which was created primarily for the government.

Throughout the 1950s, Tōkyō Tsūshin Kōgyō would use a shortened version of their name, Totsuko, in marketing within Japan, but this name was not used in western countries like the United States as it was determined to be too difficult to pronounce.

As a result in 1955, the company would start using the name Sony on some of it’s products, which was chosen as a mix of two words, the Latin word “sonus” which is the root of “sound”, and “sonny” which was a slang word for a young person. The idea behind the two words was that the company name Sony would evoke youthfulness while keeping in line with the company’s audio roots. In 1958, the company would abandon it’s Japanese name and officially become known as Sony.

Sony’s TR-series of transistor radios were their first internationally marketed product using the Sony name and were an immediate success all over the world. The TR-63 was the first Sony product sold in the United States. A fun fact about the TR-63 is that it was marketed as a pocket-sized radio, but was slightly larger than the pockets found on most men’s shirts of the day, so Sony had specially designed shirts made with oversized pockets to be used by salesmen to show off the pocketability of the slightly larger radio.

Throughout the 1960s, Sony’s place in the market grew by leaps and bounds. They created the world’s first fully transistorized television in 1960 and their transistor radios were extremely popular with American teens and others looking to take their music with them. By the 1970s, Sony had expanded into a large number of other markets including their own life insurance company and were one of the early developers of the Compact Disc.

In the 1980s, Sony was on a roll, creating the Betamax video cassette format, the Walkman, the NWS-830 personal computer, in 1988 bought CBS records, and in 1989 bought Columbia Pictures extending their reach into markets far beyond that of simple handheld radios.

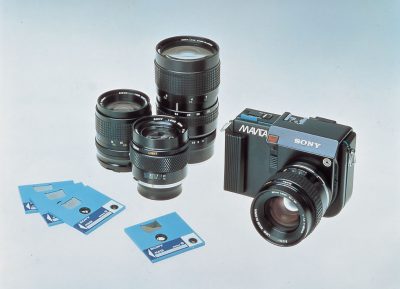

But it was another invention from 1981 that barely made a splash on anyone’s radar which later would have a ripple effect of which we are still feeling the effects of today. On August 25, 1981, Sony would announce the release of the Sony Mavica, the world’s first filmless electronic still camera. The name Mavica is said to stand for “MAgnetic VIdeo CAmera”, and wasn’t a true digital camera, but rather a type of motion video camera that captured still images and stored them on a proprietary 2 inch “Mavipak” floppy disk format that Sony had developed for the Mavica.

The Sony Mavica was the first still video camera in the world and was presented in a familiar SLR style with it’s own unique interchangeable bayonet lens mount. Three lenses were available for it, a 50mm f/1.4, a 25mm f/2, and a 16-65mm f/1.4 zoom. The image to the right shows the Mavica with all three lenses (the 50mm f/1.4 is shown twice), and a couple of the Mavipak 2″ disks.

Images stored on the camera could only be displayed on a television or video monitor connected to the camera. The images had an approximate resolution of 570 x 490 which had it been a digital camera, would have been stated as 0.27 megapixels. Each Mavipak disk could hold up to 50 images on a single disk.

The camera had an ASA 200 equivalent sensitivity and only a single 1/60th shutter speed. The metering system displayed LED arrows visible in the viewfinder and required the user to manually change aperture on the lens to get the proper exposure.

I can only imagine the excitement this camera must have received when it was first announced as it gave the first glimpse into a filmless future. Although only ever produced as a prototype, the design of the camera seems really well thought out, suggesting that the prototype was fairly close to a production model, yet the camera never went on sale.

Sony would release a couple different Mavica prototypes in the years that followed, but it wouldn’t be until 1987 when their first commercially available model, the Mavica MVC-A7AF would hit the market. Using the same still video capture onto 2″ floppies (now called VF or video floppies), the MVC-A7AF had a full range of shutter speeds and automatic focus, but lost the interchangeable lens mount, instead featuring a fixed 6x 12-72mm zoom lens.

Despite this small spattering of early models, Sony would remain relatively quiet in the photographic world until 1997 when they would relaunch a new lineup of Mavica cameras. This time instead of still video technology, the cameras would be true digital cameras, writing images to a standard 3.5″ magnetic floppy disk that could be read by any Windows or Mac based PC.

The Mavica came at the right time both for Sony and the world. Sony was expanding their presence in more industries from video games to desktop PCs to digital cameras. The world was ready for filmless cameras more than ever before and with Sony’s expertise in video camcorders, they put their existing knowledge to the test, first with the Mavica series, but then in 1996 with the CyberShot series.

The first CyberShot camera, the DSC-F1 featured a digital 350,000 pixel 1/1.3″ CCD sensor and wrote JPG files onto 4MB of internal memory. In the coming years, new models in the CyberShot series would be released at breakneck speeds, with each new model more advanced than others that came before it. Soon, pixels were measured in the millions instead of hundreds of thousands, flash storage became normal first with Sony’s own Memory Stick format, but later with universal SD and CompactFlash cards.

Many of Sony’s early CyberShot cameras took a lot of influence from Sony’s video camcorders of the era. Sony was one of the first digital camera makers to take digital video seriously, including it in most of their early models. Video options on other early digital cameras from other makers were often implemented as an after thought with very poor quality or without features making the video easy to share. In addition, Carl Zeiss zoom lenses, body designs, and even some of the electronic features that Sony pioneered for home videos carried over to these early digital still cameras.

Nothing showed that camcorder to digital camera connection more than the Sony CyberShot DSC-F505 from 1999. Featuring what was then a very controversial design, the DSC-F505 featured a large Carl Zeiss Vario-Sonnar 5x zoom lens mounted to a swiveling body that allowed the camera to shoot at upward and down angles while still being able to see the 2.0″ TFT screen.

An updated model called the DSC-F505V came out a year later with an updated CCD sensor that upped the effective resolution from 2.6 megapixels to 3.3.

In 2001 and 2002 came two more models in the series, the Sony CyberShots DSC-F707 and DSC-F717. Both models shared a similar large zoom lens and swiveling body design, but improved the lens to cover the larger sensor, still with a 5x zoom, but improving the speed wide open to f/2. Also improved was the 5.0 megapixel CCD sensor which was physically larger and offered better sensitivity in low light. The DSC-F717 was largely the same camera, but with quite a bit of tweaks to the auto focus system, auto white balance, overall speed, support for USB 2.0, and a faster top 1/2000 shutter speed.

Each of the cameras in the CyberShot DSC-F series were Sony’s top of the line digital cameras at the time of their release and carried MSRPs around $1000, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to around $1500 today. It is not clear how well these cameras sold, as digital cameras were still pretty new at the consumer level and professional photographers likely stayed true to interchangeable DSLR designs.

In 2003, Sony would release one last model in the series, the CyberShot DSC-F828, improving nearly every aspect of the camera, plus adding a large number of software features not available in other cameras at the time.

The DSC-F828 had a new Carl Zeiss 7x zoom, still with a maximum aperture of f/2 wide open, a new 8 megapixel CCD sensor with improved color accuracy due to it’s RBG+E (Emerald) pixels. The camera had both a higher resolution electronic viewfinder and rear LCD, improved auto focus, faster burst speed, support for both RAW and JPG files, a CompactFlash memory card slot, a mechanical (opposed to electronic) zoom feature which gave the camera a better feel that would appeal to pros, a new black body that resembled professional cameras at the time, and a huge number of other software features.

Like the others in it’s series, the DSC-F828 had an MSRP of $1000 and a street price of around $850. With a huge number of upgrades from previous models, the DSC-F828 was the best bargain of the bunch. Upon it’s announcement in August 2003, the DSC-F828 was the first 8 megapixel camera under $1000 and offered a higher resolution than most DSLRs of the time.

One particularly interesting feature that was introduced in the the earlier DSC-F707 which made it into the DSC-F828, is what Sony called “Night Shot” which was an infrared technology borrowed from their higher end camcorders. Night shot (and the similar “Night Framing” modes) rely on both an IR emitter on the front of the camera, and the ability for a visible light filter that is normally placed in front of the digital camera sensor to swivel out of the way. To better understand Sony’s Night Shot feature, you need to know a little more about how digital camera sensors and the human eye perceive light.

Science Stuff

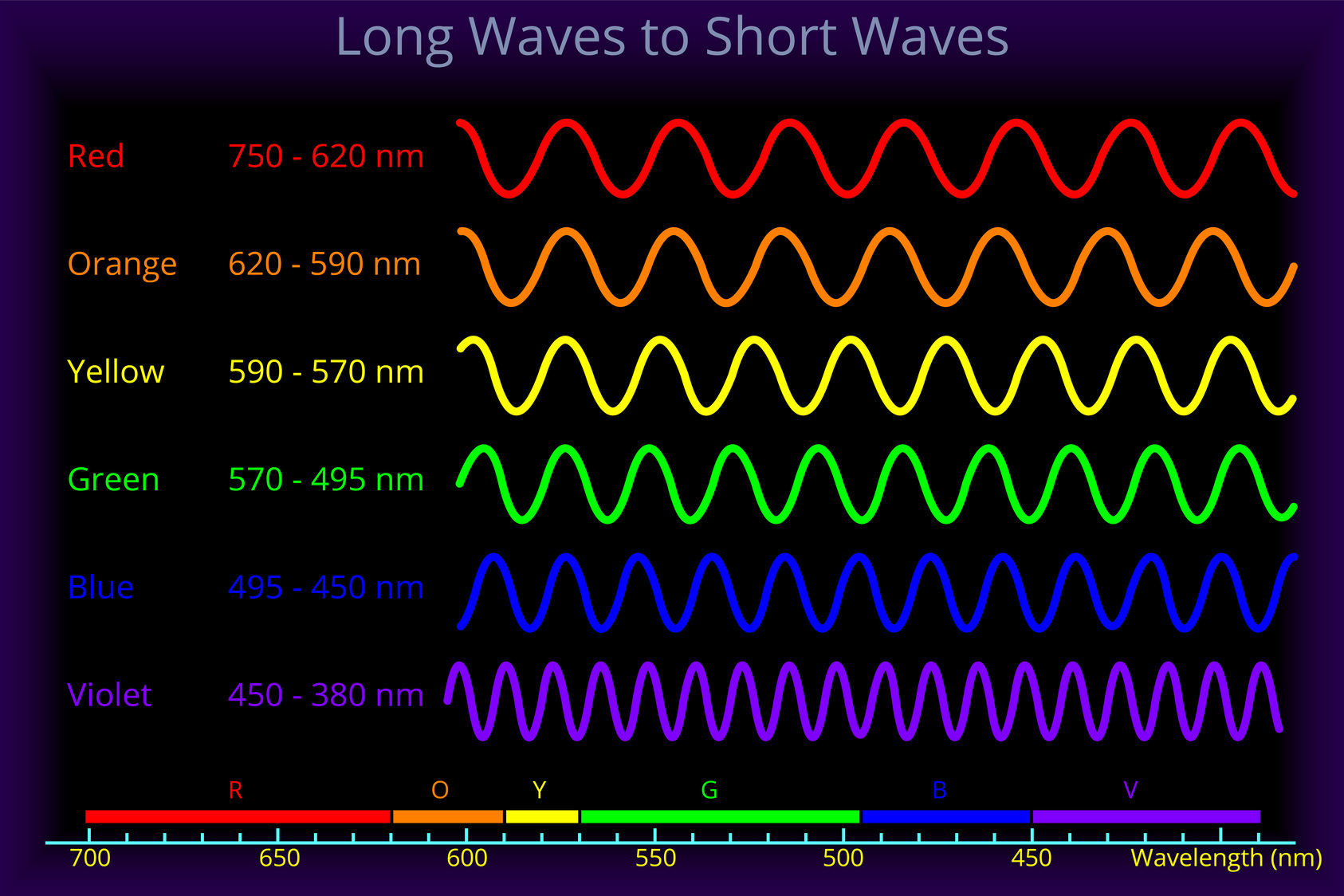

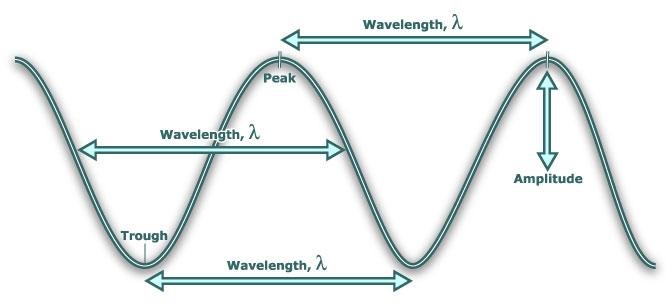

In high school science class, you may remember that light travels as a wave. Light is all around us in a variety of wavelengths, some the human eye can see, some that it can’t. A wave consists of peaks and troughs. The distance between two peaks or two troughs is called the wavelength. As the wavelength changes, the properties of the light change as well.

For most people, the human eye can detect light with a wavelength of between 380 and 750 nanometers (there are 1 million nanometers in a millimeter). We perceive light between these two wavelengths as color, with violet on the low end and red on the high end. Beyond the visible spectrum of light on the low end is ultra-violet light, and on the high end is infrared. Light beyond the visible spectrum is around us all the time, we just cannot see it, at least not without help.

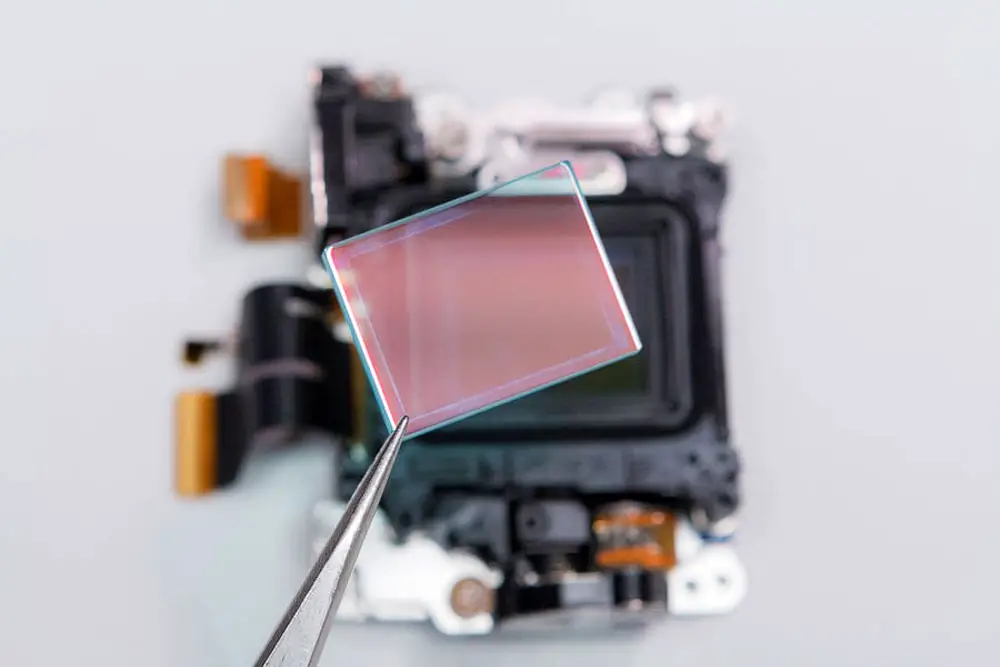

All digital camera sensors made back then and today, can detect a wider spectrum of light that can see beyond what the human eye can see, from about 350 to 1000 nanometers. While the difference on the low end between 350 nm and 380 nm is small and would have little effect on the sensor’s performance, the difference on the high end from the 750 nm limit of the human eye to the 1000 nm limit of the sensor, is a problem.

In order to more closely match the spectrum that the human eye can see to what a digital sensor can see, all digital cameras have a visible light filter applied over the sensor to restrict the light that passes through it. Without this filter, digital sensors would be taking in more information than is needed, which would change the look of the images that the camera displays.

Cameras with Sony’s Night Shot feature have that same filter over the sensor to block unwanted wavelengths, however unlike most other digital cameras, that filter is on a hinge and can be electronically controlled by the camera for special purpose photography. Combined with an IR emitter on the front of the camera, which is essentially a flashlight that only emits IR which our eyes (and filtered digital sensors) cannot see, when used together, the visible light filter moves out of the way, allowing the sensor to see the full spectrum of light, including the IR light being projected from the front of the camera. Since the human eye cannot see this light, but the camera can, the sensor is able to focus on the IR light in complete darkness.

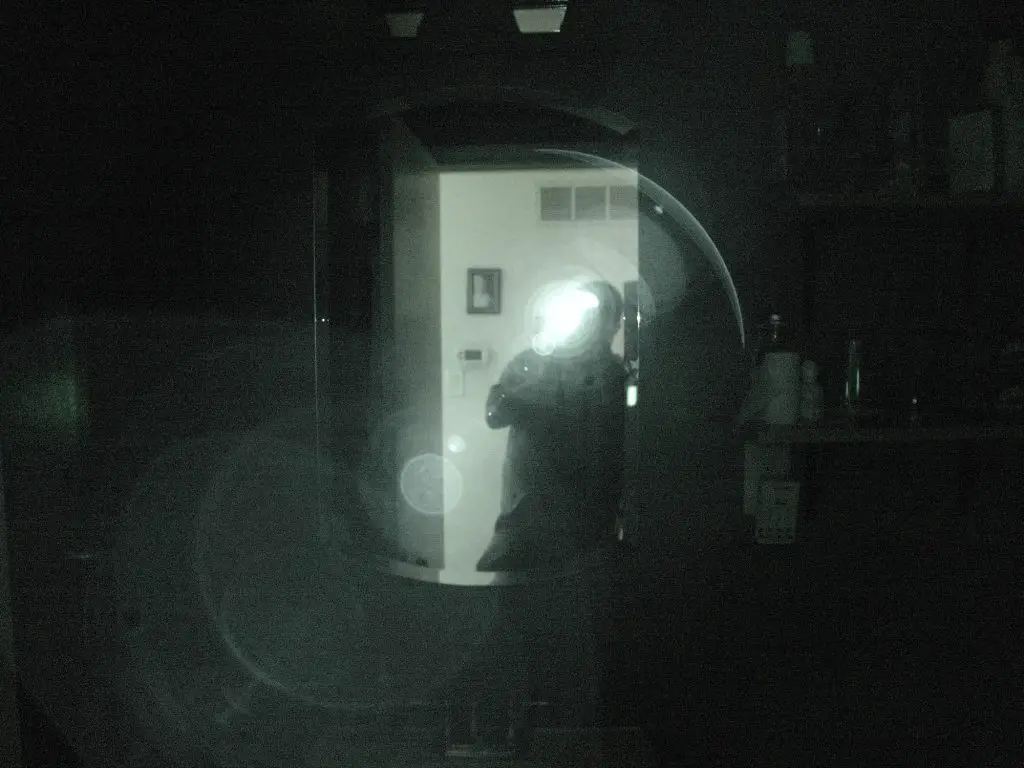

Sony uses this feature in two different ways. In the main Night Shot mode, IR light is emitted by the camera, the visible light filter moves out of the way, and the camera takes pictures of just the IR light in complete darkness. Although IR light cannot be seen by the human eye, the sensor can now see it, and it stores these images with the IR light changed to green, giving that “night vision” look that is often associated with electronic night vision devices. Although Night Shot images are presented in green monochrome without any other colors, they are an effective way of photographing objects such as sleeping babies in complete darkness.

A second Night Framing mode starts out the same way, using the IR emitted to shine light over a dark scene, and the visible light filter moves out of the way so that the digital sensor can focus and meter for whatever you are attempting to photograph, but at the moment of exposure, the IR emitter turns off, the visible light filter moves back in front of the sensor, and the camera fires it’s flash and shutter to capture a normal flash image in full color of objects in complete or very low light.

For anyone whose ever attempted to take photographs in complete darkness, you’ve likely encountered difficulties with the camera being able to focus on and meter for the extremely dark scenes. Even modern digital cameras and smartphone cameras today still struggle in very low light as they simply cannot “see” objects in complete darkness. With Night Framing mode, the camera uses it’s Night Shot technology to focus and meter for your shot, but then makes a normal flash exposure using the information it obtained using the IR light.

End Science Stuff

The Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 would be Sony’s last camera in the series and the last with the Night Shot feature. A combination of some scandalous uses of the feature, plus a widespread misunderstanding of the technology caused it’s removal in future models. By the mid 2000s, DSLRs had gained much more popularity as did more traditionally styled point and shoot’s so an oddly shaped top of the line camera with a $1000 price tag likely caused it to sell poorly.

Sony would never release a camera with the Night Shot feature again, and to the best of my knowledge, no other camera maker did either meaning these features are unique among this family of cameras in that they could do something that the best cameras today can’t.

I could probably end this review here, talking about a neat camera with a strange design and some cool features and that would make for a pretty interesting look back, but I’d be leaving out one more unintentional feature.

When Sony designed the visible light filter that could be moved out of the way of the digital sensor, they controlled it with magnets. At some point, some clever owners of these cameras discovered that if you used a small and powerful magnet, and attached it to the camera in a specific location, you could manually move the filter out of the way, essentially turning the camera into a full spectrum digital camera.

Now, you might be thinking, why would anyone want to do this? I thought you said that the reason these filters exist in the first place is to filter out light we can’t see, and that by including that light, we’d have undesirable images?

That is true, however by eliminating the filter and exposing the sensor to the full 350 nm to 1000 nm spectrum, you can use screw on filters to pick and choose which wavelengths you want the sensor to see. Since we know that IR light is around us all the time but we can’t see it, by using a full spectrum digital sensor and a screw on IR filter, you can turn the camera into an IR only camera, something Sony never designed the camera to do. When used as intended, the Night Shot mode limits the aperture and shutter speed to only specific settings to optimize low light photography. With the camera in it’s “normal” mode, but the visible light filter out of the way, the camera doesn’t have these limitations, allowing you a full spectrum of f/stops and shutter speeds, while still shooting IR photos.

Shooting a full spectrum digital camera with an IR filter in bright sunlight will produce images with otherworldly colors. Lush green trees will turn white, blues and reds will take on a purple or sometimes yellow hue. By mixing different color filters and some clever post processing, you can make your local nature park look like an alien landscape.

There is a small niche of digital photographers who will open up their cameras and permanently remove the IR filter that is permanently attached to their sensor to achieve this effect. But once these cameras are modified, they are not easily returned to normal, meaning they will only work in IR mode. Furthermore, most cameras that are modified this way are usually point and shoots as they’re the easiest to work with.

With the Sony DSC-F828 and the two models that came before it, swapping back and forth between full spectrum and normal mode is just as simple as attaching and removing a magnet. You can change back and forth as often as you like with no damage to the camera!

Today, because of this ability, plus it’s excellent f/2 Carl Zeiss lens, 8 megapixel sensor, ability to write RAW files, and it’s screw on filter mount which makes using IR filters very easy, the Sony DSC-F828 has developed a bit of a cult following for IR photographers. These cameras are one of the easiest entry points into IR photography, and for those times you want to turn the feature off, you still have a pretty good regular digital camera.

My Thoughts

Since my first camera review in December 2014, I’ve always prioritized interesting or historically significant cameras in what I write about. I’ve never limited myself to any one specific type, film format, country, or maker, and I’ve certainly not limited myself to film only cameras. When I posted my first digital camera review of the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro back in January 2017, I felt like I had to explain why a digital camera review was on a film camera site.

Since then, I’ve reviewed other filmless cameras and I’ll continue to do so, as long as they meet my criteria of being interesting or historically significant. I think that the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 definitively qualifies, not only for it’s strange appearance and unusually high-spec (for the time) list of features, but also of it’s ability to shoot full spectrum digital images without needing to modify the camera.

While I am hardly the first person to write about the DSC-F828, I think that this model’s familiarity has waned in the nearly two decades since it’s release, so perhaps it’s time for an updated review.

I first learned of the Sony Cybershot DSC-F828 while talking to my friend Adam Paul, who operates an Etsy store where he sells a huge variety of expired and rare films which he hand rolls into cassettes. Earlier in 2021, Adam got the bug to try IR photography and began with modifying Panasonic Lumix point and shoot cameras by removing the visible light filter over the digital sensor, permanently turning them into full spectrum cameras.

When Adam learned of a Sony camera that could accomplish the same task with a magnet, he did what any rational camera enthusiast would do and went out and bought 4 of them!

Although the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 is notable for the IR “hack”, even without it, this is still a pretty cool camera worthy of anyone’s attention who likes the challenge of shooting with a 20 year old digital camera.

From a purely digital standpoint, you get a Carl Zeiss zoom lens with a fast maximum aperture of f/2, an 8 megapixel CCD sensor with RAW capability, an electronic viewfinder that’s not that far off from those found in modern digital mirrorless cameras, support for both Compact Flash memory cards, and a standard mini-USB port meaning that you won’t have to jump through hoops to get it’s images off into your computer.

With a weight of 930 grams including the battery and memory card, the camera has a substantial, high quality feel to it. The black pebbled body covering looks great and the combination composite and metal body are on par with mid level DSLRs like my Nikon D7000. I am unsure if the body is weather sealed, but even if it isn’t, I would feel very confident using this camera in a light drizzle or during normal midwestern United States winters.

The body does not creak or groan, and even tilting the large zoom lens up and down requires just enough force so as not to have it flop around, but also not feel overly tight. Although this is the only DSC-F828 I have ever held, Adam confirmed that the other three he has have the same level of quality, suggesting that most should hold up well today.

There are many ways in which the DSC-F828 shows it’s camcorder roots, and the arrangement of buttons on the camera’s left side is one of many. Most the functions of these buttons are self-explanatory, so rather than explain what each one does, I would encourage anyone interested in using this camera to check out the user’s manual linked to in the specifications section above.

Up top, the DSC-F828 appears to be two cameras in one. On the right side is what looks to be a typical SLR-esque bridge camera, but on the left is the very large hinged zoom lens and flash hot shoe.

A small LCD on the top plate displays critical information like selected shutter speeds and aperture, exposures remaining, flash status, and a few others.

To the right of the LCD is a pretty standard PSAM mode dial with extra options for video, playback, scene modes, and the camera’s setup. Around and above it is the power switch and buttons to adjust white balance, +/- exposure compensation, and an LCD backlit button. Finally, near the front edge of the grip, in comfortable reach of the photographer’s right index finger, is the large chrome shutter release button.

Although a bit cluttered, the depth and size of the camera’s grip makes it very comfortable to hold. You can easily balance the weight of the camera one handed, even with the large zoom lens, without fear of dropping the camera.

Around back, there is the opening for the electronic viewfinder, 1.8″ TFT rear LCD, and a variety of buttons that once again, I won’t explain but are all pretty self explanatory. The LCD pales in comparison to modern day digital cameras, but 18 years ago when this was a current model, likely was one of the best out there. It’s good enough to compose with outdoors in bright light, but with only 134,000 pixels, isn’t sharp enough to review previously shot images in fine detail.

Above the LCD is an up/down/left/right control stick which is used to maneuver through the camera’s various menus displayed on the LCD.

To the right of the LCD is a switch that chooses between the MemoryStick storage (located inside the battery compartment) and CompactFlash storage on the right side of the camera. A second slider unlocks the CF compartment door.

As Sony’s proprietary MemoryStick format has not been used by a modern digital camera in quite a while, your best option to use the DSC-F828 today is with CF cards. Although I only had access to a couple ones I had laying around, the camera had no trouble reading and writing to a Unigen 16 GB card.

The Sony DSC-F828 lacks an optical viewfinder like a DSLR of the same era would have had, but thankfully, it’s electronic viewfinder is quite good and the one I preferred using. With 235,000 pixels, the viewfinder screen is sharper than the larger rear LCD at only 134,000 pixels.

With the camera to your eye, you get the benefit of the same information you can see on the rear screen, including battery life, exposure mode, image quality settings, remaining exposures, ISO speed, focus area, EV compensation, and selected shutter speeds and f/stops.

Although all EVFs are a drain on a camera’s battery, I found I got much better life out of the aging 18 year old battery when using the eye piece viewfinder. I won’t go over all of the things you can see in there, but nearly every critical setting you would need in whatever mode you’re shooting is there, just like you’d expect.

The bottom of the camera is where the door to the combined battery compartment and MemoryStick storage is. Also on the bottom of the lens is a standard 1/4″ tripod socket and a secondary, non-threaded hole which I assume is to stabilize the camera on certain tripods.

The DCS-F828 uses a 7.2v Sony NP-FM50 Lithium-Ion battery pack, that despite being nearly two decades old, still charged well and held enough power to survive an hour long shooting session. Of course, as is the case with any rechargeable battery, your mileage may vary, so you may need to consider an aftermarket replacement such as those found on Amazon.

The Sony DSC-F828 is a blend of old and new. It’s strange shape and unfamiliar design harkens back to the early days of digital photography when the status quo hadn’t yet been set, but with a feature set that isn’t that far off from digital cameras today, it feels somewhat out of place, especially when you learn that this is an 18 year old camera.

Working for the camera is a really good digital sensor that is capable of images with incredible detail and accurate colors, and a wide variety of features, some of which you cannot find on any currently made camera. In order to get the most out of this camera, you’ll definitely want to spend some time with the manual, but if you want to just pick it up and start shooting, it’s easy enough to get going right away.

Whether you’re in the market today for a walk down memory lane or a camera with some cool features, there’s a lot to love about the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828, but what do it’s images look like?

My Results

I don’t test a lot of vintage digital cameras, but when I do, I like to try and use them in situations similar to how they would have been used when new. The Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 was a premium bridge camera when it was released, meaning it would have catered to hobbyist photographers who liked cameras that were loaded with new technology.

Typically, professional photographers stay away from cameras like these as their confusing interfaces and new state of the art features could mean they’re less intuitive to use or that the massive amount of technology might lead to reliability problems down the road. A professional photographer makes money with his or her camera and needs to depend on that camera to perform reliably 100% of the time without fail, and having one loaded with new technology isn’t always ideal. In the film world, the DSC-F828 is like the technologically advanced Nikon FA, compared to the more dependable professional Nikon F3 or even F2.

That’s not to say that the DSC-F828 is incapable of professional quality shots, you’re just not likely to find one at a wedding, or in a photo studio.

The images above represent the best of what an 8 megapixel digital camera could offer back in 2003. Anyone willing to fork over $1000 for a camera like this would have expected excellent images with sharpness, color saturation, and details far exceeding that of typical consumer digital cameras, and that’s exactly they would have got. Comparing these images to a Nikon D40 I had a chance to play with back in 2006, they look nearly indistinguishable.

The fast Zeiss optics are excellent, and far exceed that of a consumer zoom lens, even by today’s standards. I have no evidence of this, but I believe the lens would benefit if it could somehow be transplanted onto a modern day digital SLR or mirrorless, as I believe the 8MP sensor on the DSC-F828 is not able to fully resolve all the details this lens has to offer.

With the added bonus of RAW capability, I can import these images into Adobe Photoshop CC and use Adobe RAW to further tweak the images to my heart’s content. At a resolution of 3264×2448, the quality of these images is more than enough for online photo sharing in 2021, and certainly exceeded that of most computer displays from 20 years ago.

The Sony DSC-F828 was a great camera in 2003 and it still is today. Despite not having the pixel count of current digital mirrorless cameras, I am confident that if I ever found myself in a situation where this was the only camera I had, and I needed to photograph a precious moment, that it would not disappoint me.

Of course, that’s not really why you’re here. For as good as this camera is, there have been many great digital cameras made over the last 20 years, what you really want to know about is how does it handle shooting IR?

I have never shot digital IR images before. I had seen examples of what they look like online, but I never had access to any cameras where the visible light filter was removed, so my immediate reaction when I saw my first “Digital IR” photos was….these don’t look like the ones I saw online.

Before I get ahead of myself however, I should explain how I achieved these images. The first step is to use a strong magnet to activate “Night Mode” which really just moves the visible light filter out of the way, allowing the digital sensor to see the full spectrum of light. When you have the mirror in the right position, you will hear a click as the filter moves, plus your viewfinder will change colors. If you shoot the camera like this, the sensor is going to take in much more information than it otherwise would, and you’d get wildly overexposed images with low contrast and hardly any detail.

In order to achieve the otherworldly results you often see with IR photography, you need to add an IR filter in front of the lens by screwing one on. The DSC-F828 uses a 58mm filter ring, so any 58mm IR filter will work. Not all IR filters are the same, however. You’ll notice that IR filters will usually be measured in nanometers (or nm). The exact starting and stopping wavelengths of IR light vary depending on who you ask, but most people agree that anything between 750 nm and 1000 nm is infra-red.

The most common consumer level IR filters start at 720 nm and go up from there. These filters can sometimes be called “R72 Filters” depending on who makes them. You can also get some filters that start higher, at 780 nm, 850 nm, and even 950 nm. The higher the number in nanometers, the more restrictive the filter is. To the naked eye, these filters will appear totally black. There are also “near-IR” filters that allow a small amount of visible red light through and start a lower number, such as 530 nm, 650 nm, and 680 nm. These filters will have a deep red hue as you are able to see some of the visible red light coming through, but will still look very dark. There are even variable IR filters which combine a near-IR filter (usually 530 nm) with a polarizer that allow you to achieve the effect of multiple wavelengths in the same filter.

For my first experiments, I went with a 720 nm filter and later changed to a variable filter that had a range of 530 nm to 750 nm. The nice thing about using the variable filter is that you can see the changes the different wavelengths make to your image through the electronic viewfinder. You can use both the rear LCD or the eyepiece viewfinder on the DSC-F828 for this.

Note About DSLRs Although this isn’t a problem for the DSC-F828, if you are trying IR photography with a modified DSLR, you will not be able to compose through the pentaprism as this is seeing light through the dark filter. On modified DSLRs, you will only be able to compose your images through the rear LCD using “Live View”. If the DSLR you are using does not have Live View, you will not be able to preview your images with the IR filter attached.

In my initial experiments, I found that I had more contrast at lower wavelengths. As I got closer to 750 nm, almost all color in the image disappeared, turning the entire image white. I did not have access to an IR filter higher than 750 nm, so I can only guess it gets worse with higher wavelength filters.

With the filter mounted and the magnet in place, I had it set to save images in JPG + RAW mode (the Sony uses an SRF format), the ISO set to 64 in daylight and 400 in shade, and white balance set to manual. I was told to use a custom white balance while pointing the camera at green grass, but I am uncertain of what benefit this would have as white balance shouldn’t have an effect on RAW images, but I did it anyway.

From there, I walked around my neighborhood shooting images of nature and other things. With the camera in Programmed AE mode and auto focus on, I let it calculate everything else on it’s own. When I had the ISO set to 64, bright outdoor scenes had enough to where fast shutter speeds were used, eliminating any body shake but I noticed when I was in shade, the shutter speeds started to get uncomfortably slow, so I raised the ISO to 400.

One last note about shooting RAW images on the DSC-F828 as it takes nearly 10 seconds to write a single file to the memory card. When the camera is writing the file, you cannot shoot another. I am unsure of the speed of the CompactFlash card I had loaded in the camera, but I have to imagine this is just a sign of the times. Cameras were just much slower back then, and with each RAW file around 15MB, be prepared for some really long write times.

Once I had enough shots, I plugged the camera into my computer using a standard USB-mini cable, and my Windows 10 PC recognized the camera immediately, without needing any obscure drivers or additional Sony software. I was able to use the built in Windows Photo Gallery to import the photos, but I found that by manually navigating to the camera using Windows Explorer, copying files from the DCIM folder was faster so that’s what I used most of the time.

With the files on my PC, I had no problems opening the SRF files in Adobe Photoshop CC Camera RAW. I did not have to download any additional codecs for it to read the files. While editing the SRF files in Adobe Camera RAW, the images looked very different from the JPGs that the camera captured, confirming my thought that white balance in RAW doesn’t really matter.

From this point, editing the images requires a lot of trial and error. I found that many of the images I shot had low contrast. It was difficult to see details in leaves and images that were shot in shade were often very soft. Infrared light focuses to a different focal point than white light does, which is why many manual focus lenses have IR focus marks on them. Although the DSC-F828 was able to compensate on some images, it wasn’t able to on all of them. Many of the images I shot came out very soft and sometimes even completely out of focus.

I’ll save you an elaborate dissertation on everything I did with every image, since quite frankly, I didn’t really know what I was doing. I seemed to get into a better rhythm with editing the cemetery photos, as I like the way those turned out better, but there were still many others I’m not sharing which were pretty bland.

If you’ve made it this far into this 7900+ word review wanting to know if the Sony DSC-F828 is the perfect solution for someone wanting to create digital IR images that look like the gorgeous ones you can find online, I should probably apologize as I can’t really answer that question. I can however, come up with a couple conclusions that might help someone wanting to try their hand at it.

- You will never get IR images like those you see online straight out of the camera, you are going to have to a lot of editing.

- Seriously, a LOT of editing!

- Experiment with different wavelengths of IR filters. I found that ones in the 500-600nm range give the most contrast, retaining some of the color of the original image which helps make editing easier.

- Editing in RAW will give you more wiggle room on editing exposure, but has no impact on the white balance set in the camera.

- Autofocus sensors will struggle to focus sharply with an IR filter, so if critical focus is important, you may need to try to focus manually.

Having played with the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828, I am very glad I did. For starters, this is just as great of a digital camera in 2021 as it was in 2003 when it was first released. The “normal” images I’ve shot with this camera have all looked excellent, and well beyond those of many early 21st century digital cameras when 1 to 3 megapixel sensors were still the norm, plus being able to use CompactFlash cards and easily connect to the USB port of a modern computer without any additional software eliminates many of the hurdles that people today often encounter with early digital cameras.

While the “IR magnet hack” is the reason I am reviewing this camera, I think that the Night Shot and Night Framing modes are the camera’s two best features as they allow you to do something that few digital cameras ever made, and none today can do. While it is impressive to see all of the cool things we can do today with augmented reality, 3D scanning, and images you can focus after you take them, no modern digital camera can compose and focus in complete darkness.

Collecting vintage digital cameras is a niche sub-hobby of an already niche hobby. While these cameras aren’t nearly as old as all the wonderful mechanical 19th and 20th century film cameras I normally review, the earliest digital cameras came from an era of great innovation. The designs and features we expect from cameras today weren’t yet written in stone when models like the Sony CyberShot DSC-F828 came out. With a huge amount of buttons, strange ergonomics, a large swiveling lens, and features that no longer exist on current digital cameras, plus a digital sensor and lens that are still capable of excellent images, the DSC-F828 is a fascinating camera and one that I think more people should consider adding to their collections.

I am still on the fence with whether or not I will continue to explore shooting digital IR, or just use this camera as it was intended, but the fact that I can do both is super cool, and probably my favorite feature of the camera.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links – Original Reviews

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Sony_DSC-F828

https://www.dpreview.com/reviews/sonydscf828/

https://www.dpreview.com/forums/thread/1158478

http://www.digitalsecrets.net/Sony/Sony828Review.html

https://photopoint.com/cameras/sony/sony-dsc-f-828/

https://www.steves-digicams.com/2003_reviews/f828.html

https://www.deviantart.com/michilauke/journal/Digital-Infrared-Photography-Very-Easy-541734592

It’s interesting to find a digital review, Mike.

The initial launch of the Sony was at the time when the five major companies, Canon, Minolta, Nikon, Olympus and Sony entered the fray with their versions of 8mp prosumer models. At the time I was using a 5mp Canon G5 and so the leap to 8mp would be a positive one. I delayed upgrading as Olmpus were the last to market and given the price of these latest models, I wanted to be certain that I’d spent my money wisely.

I didn’t get to handle the Sony as my dealer didn’t stock it, and the Nikon didn’t appeal. This left the Canon, Minolta and by now, the Olympus C8080WZ. A friend kindly allowed me to try out his Pro 1 over the weekend, and being a Canon user todate (G2 and G5) I was just a little disappointed with its ergonomics, although not its IQ. It just didn’t feel right in the hand. This left the Olympus and Minolta, both of which my dealer had in stock.

I was very impressed with the Minolta’s very high resolution evf and image stabilisation, but the surprise was just how well the Olympus sat in the hand, despite its being more chunky. And by this time, I’d read the review in Amateur Photographer. So, the Olympus it was and I thoroughly enjoyed using it. And I still have it! It’s biggest drawback, and it became too much for me ultimately, was its very slow writing of RAW files, 11 to 12 seconds, and the camera locked during this time. The move was to the Olympus 8mp E-500 with the Pro 18-54 lens, but overall I found this camera very disappointting, and I changed again. Now this bit gets interesting.

Around this time a dealer was offering an excellent deal on the Sony R1, just £499. This prompted me to check DPReview’s review and I thought wow! 10mp today isn’t much to write home about, but within this limitation, the images it produced are some of the best I have, only bettered a tad by my Fuji X-trans images. And the Sony Zeiss lens goes as wide as 24mm (equiv) and it has manual zoom, and which for me made it a no brainer.

I agree, the Sony R1 was in amazingly good early APS camera and was optically excellent. I used one for several years, and even now, the jpeg and raw files are totally useable. And, despite what the megapixel crowd will tell you, 10 megapixels will make fine prints for your wall and do just about everything a normal amateur photographer needs.

Andrew, did you ever use your R1 to document your iconic images of urban decay? Or is it a film only experience?

Those Sonys are excellent cameras, but kinda expensive on the used market. I wonder who goes and just gets four of them at once? Anyway, it’s great that you got to use one for a while. Maybe some day you’ll get your hands on an R1, that one’s a cult classic.

They seem to go for around $40-$50 here in the US which I think is pretty reasonable, but they might be more in other areas of the world. I know my friend didn’t pay more than $50 for any of the 4 he bought.

And yes, I would love to get an R1 someday, but I don’t purposely seek out digital cameras, no matter how cool they are. They tend to find me! 🙂

Ho acquistato recentemente questa Sony ed oggi mi è arrivato il filtro R72 per scattare senza restrizioni, grazie al magnete, foto infrarosse.

Davvero interessante.

Onestamente le foto normali sono molto belle ed usando il software Topaz Photo AI, sono praticamente ottimali anche per stampe molto grandi.

Ne beneficiano anche le foto infrarosse.

In passato nel 2003 avevo acquistato una Minolta Dimage A2 proprio per alcune migliorie (mirino più nitido, stabilizzazione del sensore… ) per usarlo anche nel lavoro (ho eseguito un matrimonio) e l’anno dopo, la reflex Olympus E-1 che ha definitivamente mandato in pensione la pellicola 35mm che ancora usavo.

Grazie per la recensione.

Mike, thanks so much for this post. I just picked up an 828 on eBay because of your post. I am interested in IR photography. I once had a Canon Powershot G12 that was IR converted by Life Pixel (I dropped it and messed up the LCD). I was listening to the Cameraosity Podcast (I very much enjoy it) when I heard about the 828, which sent me to your site. In the early 2000s, when the 828 came out, I used Olympus E10 and E20s 20s to do candids at weddings and then posted them to my website the day after. (I was a wedding photographer for 40 years) and I would use them for some personal travel photos. I had to go back and look at some of the images from those 5 and 6 mp cameras, and I was surprised at how good they are.I look forward to using that 828 for regular and IR photos.

I am glad you found my article helpful. I REALLY like the DSC-F828, in fact it might possibly be my favorite “vintage digital” camera, not just for the easy IR mode, but all of the camera’s various other functions. Once you get yours up and running, I encourage you to explore all of the camera’s other features. It shoots very nice images in regular mode. The Zeiss glasss and 8MP CCD sensor make for a wonderful pairing!