This is the Auto Fifty, a Twin Lens Reflex camera sold by the United States Camera Corporation out of Chicago, Illinois around 1955. Despite what it’s name suggests, the Auto Fifty was not made in the United States, and is actually a rebadged Beautyflex D built by Taiyodo Koki K.K. from Tokyo, Japan. The Auto Fifty shoots 6cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film and is a high quality copy of the German Rolleicord sharing many of that camera’s features, including the Bay 1 filter and hood mounts. The camera was not produced for very long as the company that made it would go out of business less than 2 years after this model’s release.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lenses: 80mm f/3.5 Biokor coated 3-elements (taking), 80mm f/3.5 Tri-Lausar coated 3-elements (viewing)

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Taiyodo Koki Synchro-MX Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1013 grams

Manual (similar model): https://cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/beautyflex_model-d.pdf

How these ratings work |

The USC Auto Fifty is a quality made Japanese camera produced for an American company with a unique face plate. Unlike other USC cameras, the Auto Fifty is well built and has an excellent lens. It supports most of the same features as other quality Rollei copies and produces excellent images. This isn’t a common camera, but with it’s good looks, competitive features, and capability of great images, is a camera that would appeal to both collectors and shooters alike. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

The above screenshot from the camera-wiki page for the USC Auto Fifty is one of the most thorough and complete histories of a camera as any you’ll find online…

In the nearly seven years I’ve been reviewing film cameras, the most common feedback I receive from readers is their appreciation for how much history I dig up about these old cameras. While I love to use old cameras and see the photos they make, it’s the history of them that fascinates me the most and the reason why I keep doing what I do.

In the case of the USC Auto Fifty, the two sentences above was all that I could find when I first started researching this camera. If I had to change one thing about camera-wiki’s description it’s that I would change their use of “probably” to “definitely” as the Taiyodo Beautyflex D is definitely the camera the USC Auto Fifty is a name variant of.

Of course, I knew I could do better than two sentences, so I pulled up my big boy pants and got to work!

In order to tell the complete history of the USC Auto Fifty, we should first start with the name on the camera, “United States Camera Corporation” which most certainly is not the name of the company that made this camera. Instead, USC appears to be an alias to that of the Pho-Tak Corporation of Chicago, Illinois.

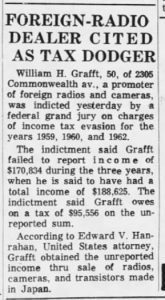

Very little is known about the history of Pho-Tak or who worked there. The only name that has ever come up in the company’s history is William H. Grafft who held some sort of leadership position, possibly President, at Pho-Tak. Grafft would eventually be convicted of tax evasion as the short Chicago Tribune article to the right from April 1966 explains.

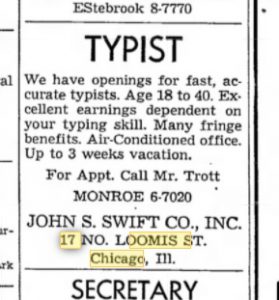

Pho-Tak’s address is most commonly reported as Pho-Tak Corp, 17 North Loomis, Chicago 7, Illinois, but I’ve also seen 15 and 21 North Loomis reported as well. In my research for this article, I found another company called American Photo Laboratories whose address is 28 North Loomis, Chicago 7, Illinois who produced film cutters, bulbs, and other photographic accessories.

Not finding any conclusive evidence of what relationship these companies all had with each other and why their addresses were so similar, I decided to expand my search for 17 North Loomis in Chicago to newspaper articles from later in time. That’s when I stumbled upon an ad from May 1964 for the John S. Swift company with the same address.

Assuming I had just found a later tenant to that building, I did a Google search for the company and to my surprise, they are still in business, and according to their company website, have been in business since 1912.

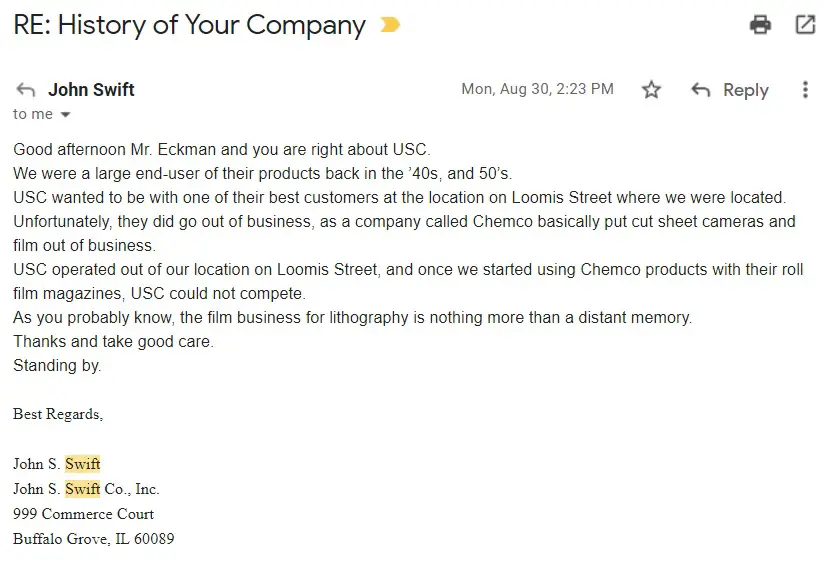

On a wild hunch, I sent an email to the company contact address on their site, introducing who I am, and explaining the connection of 17 North Loomis, and asked if anyone there knew of any connection with Pho-Tak or USC.

To my amazement, within an hour of my email, I received a response from John Swift, the current owner of the company, confirming that not only yes, was there a connection between his company and USC, but that his company owned the building that both Pho-Tak and USC were in. It turns out that 17 North Loomis Street was once a multi-unit office building that consisted of the addresses 10 through 28 which explains why all of the addresses seem to blend together.

Mr. Swift went on to explain that his company was a large end-user of Pho-Tak and USC’s products as they were in the lithograph business back then. USC wanted to be close to one of their biggest customers, which is why their operations were based out of the same building. He didn’t have any recollection of their camera business, but noted that the company went out of business once his company switched over to a competitor called Chemco whose products were superior to USCs.

Even with Mr. Swift’s information, we still do not know why the names Pho-Tak and USC were used seemingly interchangeably. In fact, evidence exists that the company also used the name “Life Time Mfg. Co. Inc.” on a camera called the “Life Time 120′ which suggests there might have been even more names.

The history of Pho-Tak and USC is confusing and vague, but what we do know is that the company probably started producing cameras around 1948 as the October 1948 issue of Popular Photography has the first appearance of the name in their year end wrap-up of cameras for the Pho-Tak Campus, Defender, and Traveler models.

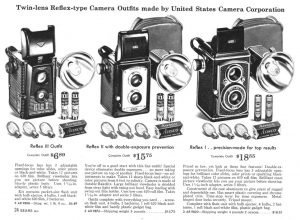

Pho-Tak cameras were usually folding or box models that used either 120 or 620 format film. They were all inexpensive models which usually came in some sort of kit with a flash and flashbulbs offered for rock bottom prices. Many of the ads I’ve seen like the one to the right were not by camera stores, rather jewelry, furniture, and other types of department stores.

Many USC models such as the Trailblazer, Vagabond, and Rollex were rebadges of identical Pho-Tak models further adding to the confusion.

One possible explanation for the existence of both names is that around 1957, the Sears Roebuck & Company started reselling USC branded cameras, and even a model called the Tower Camflash 127, which appears to be a rebadge of the USC Comet 127.

Perhaps the USC brand was created to develop a higher end identity compared to the Pho-Tak brand. With the inclusion of 35mm models like the German made USC 35, it’s plausible that the company was trying to go up-market.

One of the first higher end USC cameras was a Twin Lens Reflex called the USC Auto Forty. The Auto Forty was a rebadged Accuraflex made in Japan by a company called Tougodo Optical Company. Some sources online incorrectly state the Accuraflex was made by a company called Accura or some other distributor, but based on research by Barry Toogood of tlr-cameras.com, he concludes that the Accuraflex was a Tougodo design and spells out his reasons why on his site.

Around the same time the USC Auto Forty was available, a second model called the USC Auto Fifty was also sold. The Auto Fifty was yet another rebadge of a different Japanese TLR called the Beautyflex D by Taiyodo Koki.

Both Tougodo and Taiyodo were known for making huge numbers of very similar cameras. Models with names like the Crownflex, Hacoflex, Kinoflex, Metascoflex, Toyocaflex, Zenoflex, Beautyflex (and -cord), Fodorflex, Gen-Flex, Photoflex, and Wardflex are all designs made by either company. Each one of these models had a very similar feature set of the German Rolleicord and Rolleiflex. In fact, it was this blatant copying of other company’s products that in 1959, the JCII (Japan Camera Industry Institute) created the JMDC (Japan Machinery Design Center) to reduce the number of these copycat cameras. Together, both the JCII and JMDC sought to improve Japan’s reputation, not only with camera companies, but in the manufacturing industry altogether, as a country whose products were not only built to a high level of quality, but also of unique design.

The Beautyflex D and USC Auto Fifty were well built and attractive TLR cameras with a feature set very similar to the Rolleicord IV from 1953. Featuring a Tomioka made f/3.5 Biokor lens, a flash synchronized shutter, and an automatic exposure counter, the Auto Fifty was an attractive cost effective option for the American photographer wanting a German style TLR, but without paying German prices.

In Japan, the Beautyflex D sold for 11,000 yen, which was more expensive than basic Japanese twin lens cameras like the Ricohflex, but about half the cost of a top of the line Minolta Autocord.

I could not find any information about who sold the USC Auto Fifty, or for how much. I scoured every source for ads, catalogs and period magazine articles, and came up empty. In the 1959 Sears camera catalog, three United States Camera company models are offered for sale, but are all basic models, with no mention of the Auto Fifty.

We know for sure the Beautyflex D first went on sale in 1955, but that doesn’t guarantee the USC version did as it’s possible that unsold Japanese inventory was exported and rebranded here at a later time. I fully expected to see some evidence of the camera’s sale here, but came up empty. My best guess for what it might have cost is that by using the Japanese price which was slightly less than half that of an Autocord, knowing that most Autocord models sold here for around $100, the USC Auto Fifty likely had a retail price somewhere slightly below $50, which if true, would have been a pretty good bargain.

As far as I can tell, both Pho-Tak and USC went out of business around 1960 as references to cameras made by them disappeared in newspaper and magazine articles that I found. A combination of demands by customers for better cameras, USC’s failures in the lithograph industry, and possible legal action taken against William H. Grafft all likely played a part in the company’s demise.

Today, both Pho-Tak and United States Camera are both largely forgotten brands as their short history and constant output of cheap cameras leaves little to be desired by collectors. The USC Auto Fifty was the single highest end camera made under both names, and with good build quality, a capable feature set, and attractive cosmetics does make it worth adding to your collection. For fans of simple box and meniscus folding cameras, models like the Traveler box camera or Foldex folding cameras might be worth picking up for a dollar or two if they become available.

My Thoughts

I don’t remember the first time I saw a USC Auto Fifty as I was already aware of it the second time I saw one, which was in a last minute eBay search of auctions ending soon with no bids. I threw out what I like to call a “mercy bid” which is a lowball number that’s probably less than what something is worth, but at least prevents the auction from closing with no bids. I won the Auto Fifty at the opening bid of $10 and was eager to give it a shot whenever it arrived.

Once I had my hands on the camera, I was impressed with the build quality. Although basic compared to other Japanese TLRs like the Minolta Autocord or Ricoh Diacord, I found the build quality to be comparable to those models. With a weight just over 1000 grams, the camera didn’t feel cheap or creak around in my hands. Fit and finish was excellent, the shutter seemed to work fine, and the viewing screen was about as bright as other 1950s TLRs.

If you’ve ever used a Rolleicord or any of the hundreds of copycat models made in Japan and other countries, using the Auto Fifty should be pretty familiar to you.

Starting with the camera’s right side, there is the large focus knob with a film reminder disc on the outside. Distances are indicated in feet and there is a depth of field scale, which on my example was flaking off, making it hard to read.

Above and to the left of the focus knob is the film advance knob, which has a button in it’s center which must be pressed to unlock the double exposure prevention feature when advancing to the next frame. The Auto Fifty more closely resembles the Rolleicord with it’s film advance knob, rather than the lever of Rolleiflex and it’s copies.

The word “Auto” in the Auto Fifty indicates that the camera has an automatic film stop when advancing the film. This means there is no red window on the camera for seeing exposure numbers on the film backing paper. Exposure numbers are read via the small counter above and to the right of the focus knob. After the 12th and final exposure, a red bullseye will appear indicating the end of the film.

The camera’s left side has an accessory shoe and two knobs which are both used when loading film to release both the supply and take up spools.

Both sides of the camera have a rectangular strap lug for use with a neck strap.

On the camera’s bottom is a 1/4″ tripod socket which is surrounded by a large chrome ring that doubles as the film door release. Rotate the dial in the direction of the “C” to close and lock it, and rotate it towards the “O” to open it.

The Auto Fifty uses a secure locking system in which the lock slides a metal arm foreword and back, holding the door tightly shut when closed. This is better than lesser TLRs which use a spring loaded clip to keep the film compartment shut.

In the image to the right, the camera is upside down, with the take up side near the bottom. A new roll of film would go into a compartment on what is actually the bottom of the camera, but can’t be seen in this image.

To load in a new roll of film, pull back on each of the small knobs on the camera’s left side to insert a new roll of film on the supply side. Stretch the paper leader across the metal rollers and then attach the leader to an empty spool loaded on the take up side. I often struggle loading an empty spool into the take up side on cameras like this with automatic film counters, as the geared shaft on the take up side always seems to get in the way. With practice though, it can be done easily.

With the film leader attached to an empty take up spool, rotate the film advance knob enough times to make sure the film is transporting correctly and will stay attached to the spool. In both images of the film compartment, you can see two red dots near the edge of the film compartment. You must align these red dots with the starting line of whatever film you are loading into the camera. Some films will actually say the word START on them, others will just have a double sided arrow. Whichever you have, it is really important to line up this line with these dots in order for the film transport to work correctly. The film advance knob is geared in a way which it can only rotate in one direction, so go slow, as if you go too far, there is no way to back it up without having to remove the film and start over.

Once you have a new roll of film in the camera and the arrows lined up with the two red dots, it is time to close the camera and lock the film door using the knob on the camera’s bottom. After closing the film compartment, the exposure counter should reset to “0”. The last step is to keep turning the film advance knob until the number “1” appears in the exposure counter, at which point the knob will lock and stop turning. The camera is now ready for it’s first exposure.

Like many TLRs, controlling exposure is done via two levers around the perimeter of the taking (bottom) lens. Shutter speeds from 1 to 1/300 plus Bulb are selected on the left, and f/stops from 3.5 to 22 on the right. On the side of the shutter near the 2 o’clock position is a lever for selecting the flash sync between M, F, and X. When using the M setting, there is an additional lever with a yellow tip (seen in the image to the right between the setting for f/4 and f/5.6) which sets the flash sync delay. If you have no intention of using flash on this camera, you do not need to mess with either of these levers. In fact, I recommend not touching them as that’s one more thing that could break!

A small self-timer lever with a red dot on the handle sticks out near the 5 o’clock position around the lens. As with most mechanical self-timers, unless you are certain the camera has been serviced recently, I recommend not using it as self-timers can easily become stuck which will cause problems with the shutter. Both the taking and viewing lenses support Rollei style Bay-1 attachments.

The USC Auto Fifty’s shutter is not coupled to the film transport, which means you have to manually cock the shutter before each and every shot. A small lever near the 10 o’clock position around the shutter is the cocking lever. Finally. the shutter release is in the bottom left corner of the front face.

The viewfinder has a standard focusing screen with a subtle Fresnel pattern that improves brightness. Vignetting is more visible in the corners than later TLRs so there would still be some improvement with an aftermarket focusing screen, but as it is, in bright sunlight, it works fine.

The screen has etched bright lines on all four sides to help keep the image level, but there is no indicator for parallax or any effort made to automatically correct it. With twin lens reflex cameras like the USC Auto Fifty, due to the distance between the taking and viewing lens, when at minimum focus, the exposed image will be slightly below what you see. Some companies like Mamiya and Voigtländer have added features such as moving needles and tilting viewfinders to accommodate parallax, but most leave it up to you to compensate.

The USC Auto Fifty has both a folding magnifying glass and a sports finder feature which allow for more flexible image composition. When critical focus is necessary, simply fold out the magnifying glass under the top hood so that it is parallel to the focusing screen and you can get a magnified view of the center of the screen for critical focus.

In instances where you are shooting fast action, you can fold down the front plate of the hood and then by peering through a small square on the back of the hood looking through the front opening, you can compose images quickly with the camera up to your eye. This only works when focus is at or near infinity, so I wouldn’t try using the sports finder for close ups. In the image to the right, a small chrome button near the bottom right corner of the back of the hood releases the folded down top plate when using the sports finder, so that you can return it to it’s normal position.

Since the USC Auto Fifty uses a built in exposure counter, there is no red window on the back or bottom of the camera, so when looking at it’s back, there’s not much to see, other than the opening for the sports finder on the hood.

I mentioned earlier in this article that using the USC Auto Fifty should be familiar to anyone whose used a Rolleicord or any of the many copycat cameras out there and that’s not a bad thing. Most Japanese companies like Taiyodo did a very good job at copying German cameras and the USC is no exception. Although I could never find a price of what this camera might have sold for, I am certain it would have been a steep discount from the real thing, but works like and delivers results just the same. The USC Auto Fifty is a good looking camera that feels good in the hand and has everything you should need to make beautiful 6cm x 6cm images on paper, but does it deliver in real life?

My Results

When it came time to shoot the USC Auto Fifty, I went into my film drawer and rather than grab the first thing I saw, I did a digging into the back where some older films I never use have settled, and I found a box of expired Kodak VPS III 160. To be perfectly honest, I have no idea where or when I got this film. It’s not likely something I would have bought, so it likely came in a box with some other things I received. Knowing that VPS III was a predecessor to Kodak Portra 160 and that Porra has an above average shelf life for a color film, I decided to give it a go. As the film was nearly 3 decades expired, I decided to give it an extra stop of exposure, so I shot it like an ASA 80 speed film and figured if this didn’t come out, I had four more rolls to try again.

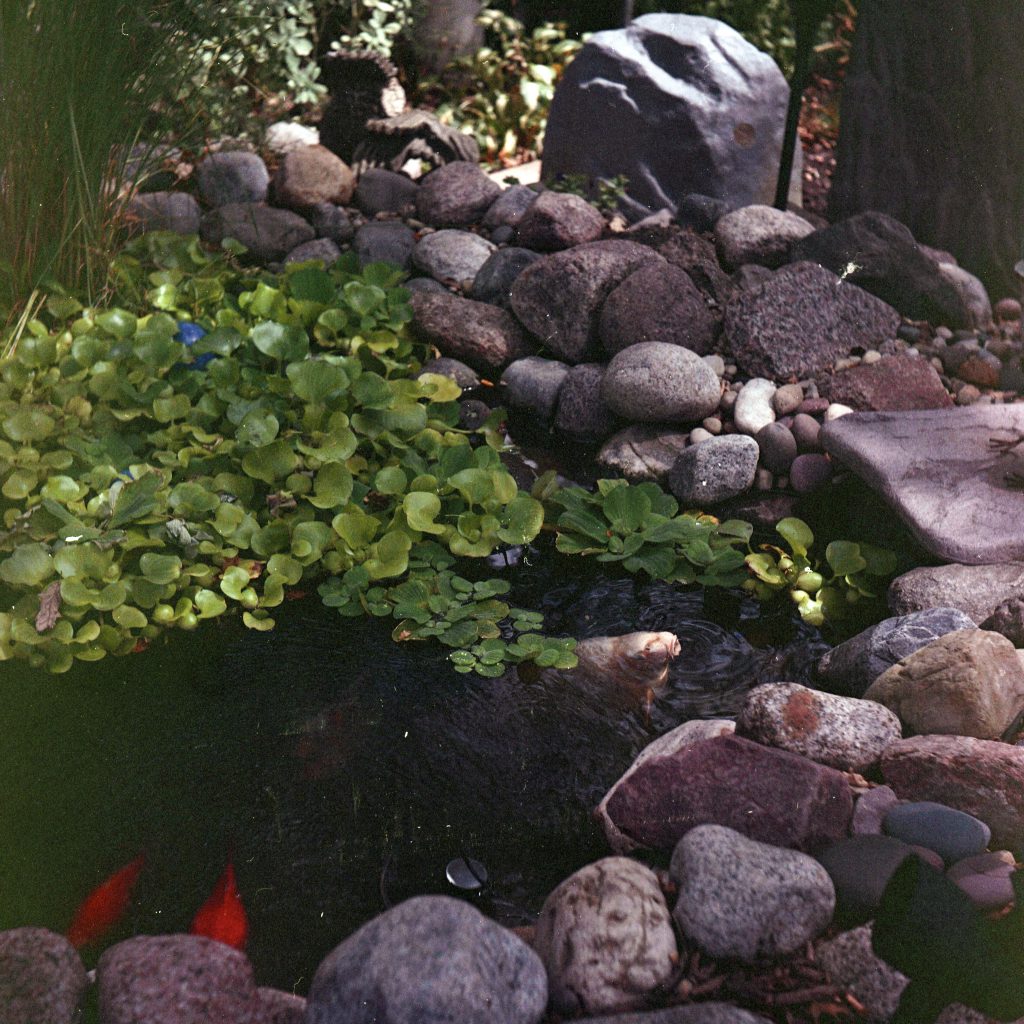

My choice of heavily expired VPS III 160 was a mixed bag. On one hand, the images came out with strange color casts and a loss of contrast, especially in lower light, but on the other hand, the images were very distinct, with a look you could only get with expired film. Even with the color casts, you could clearly see the images were sharp corner to corner with minimal vignetting, even with images showing the sky. It was obvious that the USC Auto Fifty was capable of more, so I wanted to give the camera another roll of film, this time I wanted to try some black and white, so I tapped into my growing supply of fresh Fomapan 100 Classic.

As with the expired VPS III 160, the Fomapan 100 Classic images were sharp corner to corner with very minimal vignetting. Several of the images from this roll show the sky where vignetting is going to be most evident and I don’t see it at all. Contrast seems to be a little low, which might be the Fomapan film, as this was the first ever roll of it I’ve shot. I have five more rolls, so I’ll be sure to be on the lookout in the future, but otherwise I was really impressed with the quality of images I got from both rolls.

Tomioka made the lenses for Taiyodo and a huge number of other Japanese camera makers. The 80mm f/3.5 Biokor is a Tomioka design which according to the Beautyflex’s manual says is a hard coated triplet, but considering the sharpness and almost complete lack of vignetting or other optical anomalies, I am shocked that this lens only has three elements. At the very least, I would have guessed this was a Tessar style clone, or perhaps even a higher spec lens.

Beyond the lens, I did have some issues with the frame transport on both rolls. Each time I was able to start the roll correctly, but by the 5th or 6th shot the automatic stop for each exposure stopped working. It would occasionally catch, but never at the right spot where the exposure numbers were centered in the window. This caused me to lose two exposures on the black and white roll, but as soon as I caught it, I then just paid attention to the numbers and stopped advancing when the remaining numbers were centered and that seemed to work fine. Frame spacing issues are very common on TLRs of this era with exposure counters, so this isn’t a knock on the USC Auto Fifty, but it is something a user of these cameras today will definitely want to be mindful of.

I really enjoyed my experience with the USC Auto Fifty. It worked similarly to other TLRs of the era, had no surprises and other than an issue with the exposure counter which I was easily able to overcome, offered trouble free operation. Perhaps the biggest knock I can give the camera is that it is so similar to so many other German and Japanese TLRs, there’s little unique about it that would compel someone to purchase one over several dozen similar models.

The USC Auto Fifty is an attractive and very capable Japanese camera. The fact that it was sold by a company called United States Camera is rather funny as there’s nothing American about this camera, but nonetheless, if you’re a fan of well built copies of German TLRs, you won’t do much better than this.

The USC Auto Fifty is not common, so finding one in good condition for a reasonable price will likely be difficult, but if you do manage to find one, I am certain you will think it is worth whatever you paid.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/USC_Auto_Fifty

A lot of those 50-60’s small brand Japanese TLRs are pretty capable and seem to have held up well. Not Rolleiflex but near Rolleicord.

35mm, 6×6, and half frame? I became immediately interested. Sadly, not to be.

The images look a little inconsistent from shot to shot, near field and distance, with near field being the best. Seeing the Tri-Lauser as viewing lens made me wonder, as this lens crops up a lot as a taking lens in Paul Sokk’s TLR site on early Japanese TLR’s, especially the forebears of the Yashica range, and noticing the missing screws around it, plus a Biokor branded lens as the taking lens made me wonder if at some time someone had experimented and swapped them over.

A bit of an oddity, but with a nice distinctive name plate. Nice try, Mike, but not enough this time to get me to part with my money.

SHOOT! That line is left over from the formatting template I use when creating new posts. By going off a template, it allows me to maintain consistency from post to post and those are placeholders for different film sizes which I missed in my final proofreading. Thanks for catching it.

You’re right, this camera wasn’t consistent in it’s images. It did better with the second roll than the expired color. Overall, it’s a solid camera that looks nice on a shelf, but isn’t unique enough compared to the countless of other Japanese TLRs of the era to get too excited about!

As a twin-lens fan, just another camera I’ve never even seen! Weird because I grew up in Chicago, and spent a lot of time in the 70’s and 80’s scouring camera stores for used 120 cameras!