This is a Canon Original, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by Seiki Kogaku Kenkyujo in Tokyo, Japan between the years 1935 to 1940. These cameras were the first models made by the company that would eventually become Canon. They are an evolution of an earlier Kwanon prototype that was never put into production. This camera is a less common variant that is known by collectors as the Canon Original as it lacks the “Hansa” branding, which was a trademark of Canon’s Tokyo distributor, Omiya Photo Supply Co. Ltd. Apart from the name, Hansa and non-Hansa cameras are identical. The Canon Original uses a bayonet lens mount produced by Nippon Kogaku and is always found with a 5cm lens ranging from f/2 to f/4.5.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/4.5 Nippon Kogaku Nikkor uncoated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Hansa Bayonet

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Pop Up Viewfinder and Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: Z, 1/20 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: Unknown

Manual: None

History

The earliest days of the Japanese optical industry began around the turn of the last century. Back then, Japan was trying to exert it’s military might in the East Pacific through several wars with China and Russia, and with each victory, the need for a stronger and more capable military grew. Japan being an island, they depended a lot on their navy, so the bulk of Japan’s industry was created to serve the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Japanese industry followed the practice of jikyujisoku, which is the goal of achieving self-sufficiency in manufacturing. When it came to optical goods such as rifle scopes, binoculars, and submarine periscopes, if you wanted the best, you got them from Germany, but that wasn’t good enough for Japan, so around the turn of the last century, a few small Japanese optics firms were founded to begin research into forming optical glass and building instruments.

In 1906, an optical research facility was formed in Tokyo and three years later, a repair facility was established to service optical weapons belonging to the military. Within a few years of it’s opening, these facilities gained enough experience to produce binoculars, telescopes, and microscopes for a variety of applications.

Things changed when war broke out in Europe as Japan’s own capacity was a small fraction of their total appetite for optical goods which were still being imported from Germany. By the order of the Imperial Japanese Navy, three separate Japanese optical factories, Iwaki Glass Seisaku-sho, Fujii Lens Seizo-sho, and the optical division of Tokyo Keiki Seisaku-sho were ordered to combine into a single entity.

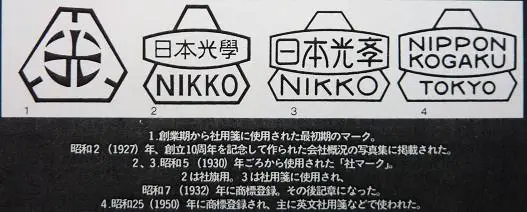

On July 25, 1917, Nippon Kogaku Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha was founded in Tokyo to become Japan’s national optics company. Nippon Kogaku was founded with ¥2,000,000 in operating capital and around 200 employees with the goal of ending Japan’s reliance on outside goods from Germany.

After World War I ended, Germany’s economy was destroyed and many people were out of work. This proved beneficial to Nippon Kogaku as between 1919 and 1921, the company recruited out of work German scientists and optical engineers to come to Japan to help the new company replicate the German designs they sought.

A total of eight German engineers would arrive in Tokyo in January 1921 with a 5 year contract to work for the company. Along with employment and salary, the families of these engineers were invited, and the Japanese provided them with housing and whatever they needed to uproot their lives and move to a new country.

Of the eight Germans, the two most significant were Heinrich Acht who was principal engineer of product design, and Professor Max Lange, who was in charge of optical lens design. After the expiration of the original 5 year contract, Heinrich Acht would remain employed by Nippon Kogaku for another 3 years.

Nippon Kogaku’s recruiting of these German engineers proved to be a huge success as by the end of the next decade, the company was able to manufacture products equal to, and sometimes exceeding those being made in Germany by their top companies like Leitz, Schneider, and Zeiss.

By 1930, Nippon Kogaku was the sole provider of optical goods to the Imperial Japanese Navy and was Japan’s top optics company, but the strange thing is, no one outside of the military or specialized scientific and medical institutions who used their products, knew anything about them.

Nippon Kogaku was a private company that didn’t make anything for commercial sale. If you were a photographer in 1930s Japan, you could live down the street from Nippon Kogaku’s factory and not know anything about the company. Even if you did, they didn’t make cameras or anything that would be useful to a private citizen.

Sensing a need for a Japanese made photographic camera to compete with the German Leica, in 1933, two men named Goro Yashida and Yashida’s brother-in-low Saburo Uchida formed a new company called Seiki Kogaku Kenkyujo on the third floor of an elegant apartment building located in Roppongi, Azabu Ward (presently Minato Ward) in Tokyo. Their goal was to produce Japan’s first compact 35mm camera. Together with two additional men named Takeo Maeda and Tomitaru Kaneko, Seiki Kogaku got to work on their new camera.

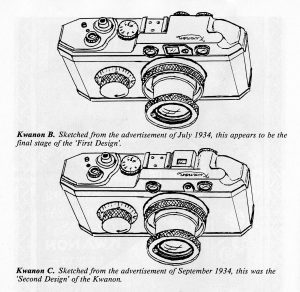

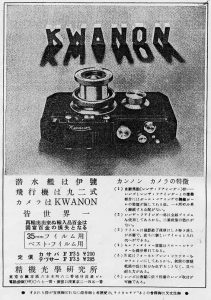

Of the four men, Goro Yoshida was in charge of the design of the new camera, which early on was given the name “Kwanon”, named after the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. The first evidence of the new camera was an artist’s drawing that appeared in a June 1934 advertisement that included the name Kwanon, along with some specifications about it. Future drawings showing some evolution of the design appeared in the July and September 1934 issues of Asahi Camera.

Despite all that was written about the history of Seiki Kogaku and the Kwanon, very few conclusive facts are known about it. In his 1985 book about Canon Rangefinders, Peter Dechert says that the actual truth of the Kwanon is still shrouded in mystery, and in the 37 years since his book was completed, very few conclusive facts have emerged.

The most common story about the Kwanon is that 10 prototypes were built, only one of which is known to survive today. This camera, nicknamed the Kwanon-X is said to have first been sold in 1937 and purchased back by Canon in the 1950s. The camera is still in possession of the Canon Camera Museum today and is credited as a genuine Kwanon.

The reality is the Kwanon-X in Canon’s museum does not look at all like the many known drawings of Kwanon prototypes that were made, nor does it look like the camera in any of the 1934 advertisements. According to Dechert, those who have had a chance to inspect this camera first hand suggest it more strongly resembles an early Hansa Canon from the late 1930s.

Who made the camera is also debated. Some say the camera was a working copy made by Yoshida to get a better sense for how a new camera should work, others say it might have been put together in the late 1930s by other Seiki Kogaku factory workers using obsolete parts they had laying around. My personal opinion is that the story of it being made up of obsolete Hansa Canon parts makes the most sense.

While the story of the Kwanon-X in Canon’s museum is the most commonly referenced surviving example, a second example sold for $138,000 in a July 2006 auction which looks much more like the real thing. This camera shares all of the known characteristics of a real Kwanon, including a convincing patina beneath it’s black paint which if I were a betting man, is much more likely to be real than the Kwanon-X.

With all the confusion and uncertainty regarding what exactly a true Kwanon might have looked like, the following are some conclusions that based on everything I’ve researched, are all true.

-

These two drawings are based off two different 1934 advertisements for the Kwanon showing models B and C. Image courtesy, Peter Dechert. There were four distinct variations of the Kwanon, which historians refer to as the models A, B, C, and D and all were painted black which is consistent with early Zeiss-Ikon Contax and Leica cameras which were also painted black.

- All four versions have a prominent dial on the front of the camera to the left of the lens mount for both the exposure counter and film advance knob. The design of these knobs could have been inspired by the Zeiss-Ikon Contax I, which functions similarly.

- The Kwanon was designed with cassette to cassette film transport in mind rather than rewindable 35mm film as none of the Kwanon drawings have a rewind knob. This makes a bit of sense as Kodak did not release their daylight loading type 135 cassette until 1934, and Peter Dechert hypothesizes that news of Kodak’s new film likely wouldn’t have reached Japan until 1935, so it is likely Yoshida came up with this design prior to that.

- All four Kwanon drawings show an interchangeable screw lens mount. Although it’s not specifically stated, we can assume that this mount used the same Leica Thread Mount since the entire goal of creating the camera in the first place was to compete with the Leica, so maintaining lens compatibility would have been a priority.

- The lenses for the Kwanon were all branded “Kasyapa” (named after Kāśyapa, later Mahākāśyapa, another Buddhist disciple) and were 50mm f/3.5 collapsible style lenses. There is no information about who made these lenses, but since Seiki Kogaku had no experience making lenses, it’s plausible some small supplier made them, or possibly never existed at all.

- The area in which the Kwanon prototypes changed the most was in the viewfinder. Models A and B both have twin openings in the back, one for the main viewfinder and the other for the coupled rangefinder. The Model A has humps on the top plate aligned with the two openings, and the Model B is flat with no humps. Staring with the Model C, the in body viewfinder was replaced with a flip up optical viewfinder in the top plate of the camera. A recess in the top plate allows this viewfinder to fold down flat with the rest of the top plate when not in use.

We can reasonably guess that development of the Kwanon continued through to the end of 1934, but in 1935, a couple of significant changes to the camera’s design were made, along with a name change. For the name, it was thought that trying to market a product named after a religious figure might offend some people, so the name Canon was chosen as it was more neutral and English sounding, plus when pronounced, it sounded exactly the same as “Kwanon”. Seiki Kogaku would file a trademark request for the name “Canon” in June 1935 and it would be approved in September 1935.

We can reasonably guess that development of the Kwanon continued through to the end of 1934, but in 1935, a couple of significant changes to the camera’s design were made, along with a name change. For the name, it was thought that trying to market a product named after a religious figure might offend some people, so the name Canon was chosen as it was more neutral and English sounding, plus when pronounced, it sounded exactly the same as “Kwanon”. Seiki Kogaku would file a trademark request for the name “Canon” in June 1935 and it would be approved in September 1935.

Two of the biggest changes to the Kwanon prototypes were the lens mount and rangefinder coupling, both of which were based off the Leitz Leica. Ernst Leitz had filed a patent in Japan for both designs in late 1934, requiring Seiki Kogaku to come up with something different if they wanted to be able to sell their camera. The third biggest change was the need to support Kodak’s new daylight loading 135 cassette, so the camera had to be modified to add a rewind knob and the ability to reverse the film transport. This change to the film transport was likely also the reason the film advance knob was moved from the front of the camera to the top plate.

The Leica screw mount was easy enough to create, but now that the patent required them to come up with something else, Seiki Kogaku had to find someone to help them design an all new mount. For this Saburo Uchida called upon some contacts he had at Nippon Kogaku and asked them for help in designing a new lens mount, and while they were at it, a new rangefinder coupling.

Having never produced anything for the consumer market, Nippon Kogaku agreed to take on this challenge, perhaps as a way to get their name out there, or perhaps they saw the mutual benefit of there being a Japanese made 35mm camera that could possibly be used by the Japanese military.

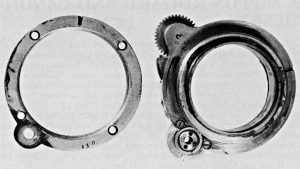

Whatever their motivation, Nippon Kogaku got to work on a new bayonet lens mount with a wheel operated focusing helix. This mount was similar to the internal bayonet used on the Zeiss-Ikon Contax rangefinder. The rangefinder coupling was via a rotating pin that is hidden beneath a round cover near the lens mount’s 1 o’clock position. As the lens was focused, this pin spun, moving forward and back through a hole in the body into the rangefinder area, moving the optical elements. This design of both the focusing mount and rangefinder coupling was different enough to not violate Leitz’s patents. Early versions of the lens mount are engraved “Nippon Kogaku” next to the serial number. This engraving stopped somewhere before number 800.

Another interesting thing about Nippon Kogaku’s new mount is that beneath it, the body of the Canon retained a 39mm screw mount, which was given the name the J-mount. Although sharing the same diameter as the Leica Thread Mount, it had a different pitch to the threads making Leica lenses incompatible.

The Nippon Kogaku focusing mount was screwed into this J-mount and secured in place via a grub screw near the bottom of the focusing mount. Although not designed to be removed by the end user, in service, the focusing unit could be separated from the body by removing this screw.

In the previous image to the right, the 39mm flange is shown on the left, removed from the camera. Notice the round hole near the bottom right (actually top right when oriented on the camera) which is where the rangefinder coupling pin passes through.

On the right is the backside of the Nippon Kogaku focusing mount which is screwed into the threaded Canon J flange and held in place by a grub screw. The rangefinder coupling in both the flange and focusing unit are shown in the same orientation (just backwards) to give you an idea of how it works on the camera.

Most of the above information is covered in greater detail in Peter Dechert’s book about the Canon rangefinder, but one aspect that isn’t well explained is how Nippon Kogaku came to produce lenses for the new Canon camera. All earlier references to the Kwanon prototypes mention an unbranded Kasyapa 50mm f/3.5 lens. Even the mysterious Kwanon-X camera in Canon’s museum is labeled Kasyapa, but it is not clear who made it. From the best of my research, Seiki Kogaku’s relationship with Nippon Kogaku didn’t happen until late 1934 or early 1935, after the four Kwanon prototype drawings were made.

While we can be reasonably certain that some Kwanon parts were made, as the earliest Canon rangefinders have pieces that almost perfectly match the Kwanon drawings, no information exists about the Kasyapa lens. It is unlikely this lens was made by Nippon Kogaku, or possibly that it was a rebranded Leitz Elmar, or maybe even that the lens never existed at all. Maybe the idea of a lens only existed on paper and Seiki Kogaku figured they would figure out the lens later.

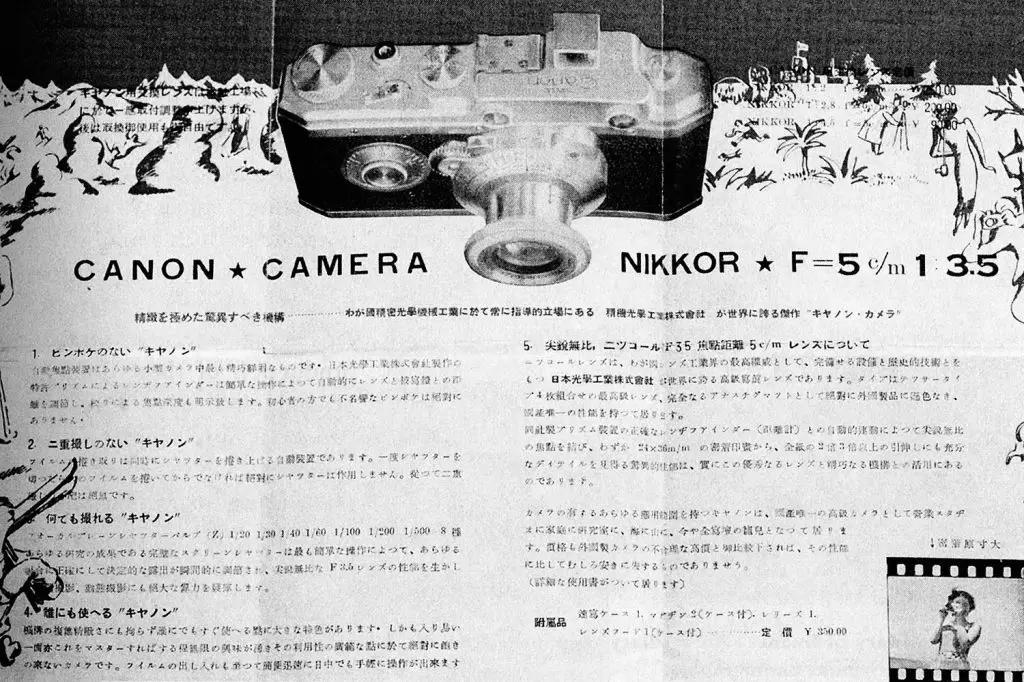

Whatever the case, in October 1935 when the earliest Canon rangefinders were shown in Asahi Camera, they were shown with a Nippon Kogaku Nikkor 5cm f/3.5 collapsible lens, along with Nippon Kogaku’s lens mount and rangefinder unit. Seiki Kogaku only handled the manufacturing of the shutter and the body of the camera.

Initially, production of the cameras was very slow. In fact, it’s possible none were available for sale in 1935 as all production was done in the same small workshop Seiki Kogaku was founded. It wouldn’t be until June 1936, when Seiki Kogaku would open their second, and much larger factory in the Meguroku area of Tokyo, did production increase.

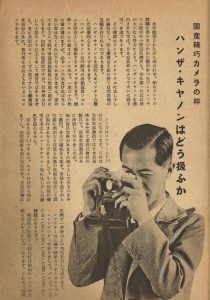

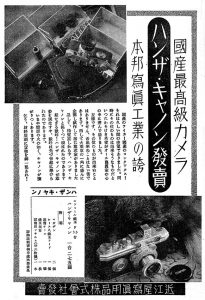

Since neither Seiki Kogaku, nor Nippon Kogaku had any experience with the retail sale or marketing of photographic goods, Seiki Kogaku relied on a local Tokyo distributor called Omiya Photo Supply Co., Ltd for sales and distribution. Canon cameras sold by Omiya were branded with the company’s trademark name “Hansa”, so the cameras were produced for Omiya with the name Hansa engraved above Canon on the top plate. A small number of Canon cameras were sold directly from the factory, and these did not have the name, so there exist original Canon rangefinders with and without the Hansa name.

Note: Many collectors refer to the original Canon as the “Hansa Canon” or “Canon Hansa”, and while not technically incorrect, this isn’t how the camera was marketed. It was simply the Canon, just like the first Nikon or Kodak cameras were called the Nikon and the Kodak. The confusion comes from many being engraved with “Hansa” above “Canon” on the top plate of those sold by Omiya. Identical cameras sold by Seiki Kogaku directly from the factory omitted the “Hansa” name, but are still considered to be the same camera.

Below is a 1936 catalog for Omiya Photo Supply which prominently displays the Canon on it’s front and back cover, along with occupying all of the catalog’s first eight pages.

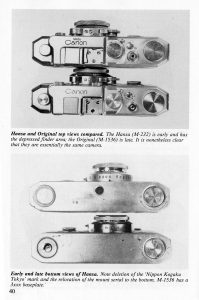

The earliest Canon rangefinders are unique from later models in that they appear to have been assembled with parts intended for the Kwanon. One of the changes made between the Kwanon and Canon rangefinders was the removal of a folding viewfinder on top of the camera, instead replaced by a pop up viewfinder that could be raised and lowered for use. The earliest Canon rangefinders still have the recess that the pop up viewfinder would have used for it’s closed position. Other suggestions that Kwanon parts were reused for Canon cameras was an asymmetrical recess under the rewind knob that looks to have been there before a rewind knob was needed, and changes made to the A/R lever suggesting it was added as an afterthought when the ability to rewind film was added.

The image to the left comes from Peter Dechert’s book and shows a couple of the more obvious differences between early and later Canon rangefinders.

In the top image, you see differences in the recess in the top plate around the pop up viewfinder, a change to the shape of the accessory shoe, lack of engraving around the A/R lever, and a different trim around the shutter release.

The bottom of the camera is different too. The early models have a centrally located 3/8″ tripod socket, which had to be there as the Kwanon had locking keys on both sides of the camera to accommodate cassette to cassette film transport, yet on the later models, a circular piece appears to be filled in around where this locking key would have been.

The original Canon camera was in production from about October 1935 to about June 1940. During that time, the camera went through three revisions. These revisions can be determined by the first digit of the serial number imprinted on the inside of the base plate. A second and unrelated serial number appears on the lens mount created by Nippon Kogaku.

It is estimated that around 1100 total cameras were made (including both Canon and Hansa Canon versions) and there is no known pattern or way of dating these serial numbers as the lens mounts were built separately from the rest of the camera, and Nippon Kogaku had a lot of trouble machining the complicated parts for the lens mount, that many were scrapped before ever being mounted to the camera. There are usually large gaps of numbers between known lens mounts as the skipped numbers were likely destroyed at the factory.

Fun Fact: In 1940, an optical engineer working for Seiki Kogaku named Kumagai Genji would leave the company to form Kōgaku Seiki-sha, meaning Optical Precision Company. The origins of this company are not clear, some say it was to build his own camera, others say Kōgaku Seiki-sha was a service center that would repair Seiki Kogaku’s cameras. The very close similarity between the names Seiki Kogaku and Kogaku Seiki suggest the latter was very possible.

Whichever story is true, Genji would later go on to build a new camera called the Nippon, which was a much closer copy to the Leica II than Canon’s camera was. The Nippon would be produced in limited numbers through World War II but after would be renamed Nicca, and in 1948, the entire company would become Nicca, maker of Nicca rangefinder cameras.

In what would foreshadow a confusing lineup of Canon rangefinders after the war, starting in 1938, new models started to appear, without any official designation or model names on the camera. Although no longer branded “Hansa” an updated Canon S would appear in October 1938. The Canon S was very similar to the original Canon, but relocated the large exposure counter on the front of the camera to beneath the film advance knob, and added slow speeds down to 1 second (the original only went as low as 1/20).

Because of Nippon Kogaku’s continued difficulty in producing the complicated lens mount and rangefinder units, in January 1939, a simpler model called the Canon J (thought to mean Canon Junior) was released without a rangefinder and without the Nippon Kogaku focusing mount. In it’s place is the Canon J screw mount which is behind all Nippon Kogaku focusing mounts. This screw mount, although cosmetically resembling the Leica Thread Mount, had a wider thread pitch that was incompatible with LTM lenses. Since there was no rangefinder, there was no need for a rangefinder coupling on the Canon J or lenses made for it.

In January of 1940, a new model, referred then as the Canon New Standard, and today known as the Canon NS replaced the original model in Canon’s lineup. The model was nearly identical to the original model, using the Nippon Kogaku lens mount and rangefinder, and lacking slow speeds. The only difference with the NS model appears to be the serial number range and that it came standard with a Nikkor 5cm f/4.5 lens.

One final new Canon would be released prior the end of World War II, which was the Canon JS in 1941. This camera is the rarest of the early Canon’s with less than 50 thought to be made, and it was simply a combination of the Model J and S as it lacked a rangefinder, had the Canon J screw mount, but also had slow speeds.

Canon would continue to release new models after the war with the J-mount, but starting in 1947 with the release of the Canon SII, offered the 39mm “semi-universal” thread mount which accepted most, but not all, Leica Thread Mount lenses. The reason for the switch back to the LTM mount was that Leitz’s German patent for the mount was no longer valid after the war, and any camera company who wanted to use it could.

In 1950s, Canon’s role as a dominant leader in the Japanese optics industry expanded greatly. Together with Nippon Kogaku and their Nikon cameras and Nikkor lenses, many other Japanese companies saw great success. In fact, the success of these companies opened the eyes of many Western countries to see Japanese companies in other industries as leaders too. Companies like Sony, Yamaha, Honda, Toyota, and Mitsubishi likely would have had a much tougher time selling their products in countries like the United States, if it hadn’t been for Canon and Nippon Kogaku.

My Thoughts

Having written reviews for Canon rangefinders like the IV Sb, P, and 7, I’ve become fond of the entire lineup. While I don’t feel the need to have one of every Canon camera ever made, there are a few more I’d love to get my hands on, and the original Canon, or Hansa Canons have been ones I’ve wanted to handle ever since I first learned of their existence.

Of course, one does not simply go out and buy an original Canon, at least not without very deep pockets, so I knew I’d have to get creative if I ever wanted a chance to review one.

Of course, one does not simply go out and buy an original Canon, at least not without very deep pockets, so I knew I’d have to get creative if I ever wanted a chance to review one.

That chance came in the fall of 2021 when I got a chance to visit the VonCabbage Collection, which is the name of a private collector who swore me to anonymity on their true name and location. I was granted permission to handle and photograph a variety of cameras in this collection for the purposes of a review, but my time with each camera was limited and I was unable to shoot film through any of them.

This Canon has shutter serial number 1536 and body serial 3160 which dates the camera to 1939-1940, making it one of the later models. It is not engraved with the name Hansa, which suggests it was sold directly from the factory. Peter Dechert says that Hansa Canons outnumber non-Hansa Canons by a ratio of three or four to one, suggesting these are much less common. To a collector though, non-Hansa Canons and Hansa Canons are exactly the same. Back then, all of these cameras were simply sold as “the Canon camera”.

When I took the Canon off the shelf, I felt a sense of reverence for such a rare and early copy of Canon’s history. Despite being made in the company’s first decade of existence, hand built in a small factory, the build quality was already very good. Although showing typical signs of age, the chrome plating was well done, the body covering wasn’t peeling, and the fit and finish was excellent.

Although the original Canon camera is still considered a Leica copy, there are quite a number of differences between the two. Unlike the Soviet made FED rangefinder, and the postwar Zorkis in which no thought was given to Leitz’s prewar patents, Seiki Kogaku made several changes to the design of the camera.

The history section above details the lens mount and rangefinder differences, but there’s quite a few others too. On the top plate, the most obvious is the pop up viewfinder which is situated between the two rangefinder windows. When stored, the viewfinder is lowered into the body, but when you need it, a small button on the rear of the camera pops it into position. Not only does the viewfinder need to be up for you to see through it, but since it sits in the light path of the rangefinder, you also need to raise the viewfinder to use the rangefinder.

Although at the time of it’s release the only lens you could get for the Canon was a 5cm (Nippon Kogaku did make a wide angle 3.5cm prototype but it never went on sale), had lenses with other focal lengths become common, mounting an auxiliary viewfinder would have likely been an issue with the popup viewfinder. I would suspect that mounting anything to the accessory shoe would have prevented the viewfinder from popping up, thus making the rangefinder impossible to use. My best guess is, that this was one of the primary reasons Seiki Kogaku stopped using it on the S-II and later.

On the right side of the top plate, most of the same controls are there as would be on a Barnack Leica, except the exposure counter. In it’s place is a large film advance knob. The knob’s diameter suggests it would have been a little easier and faster to grip than the smaller ones on Leicas. The shutter speed dial is a single piece with speeds from 1/20 to 1/500 plus Bulb (Z). This style of knob would have rotated as the shutter fired, so any contact with your hand while it was firing would have impeded the travel of the shutter curtains. There is also the A/R mode lever and cable threaded shutter release button.

Up front, to the left of the lens mount is the very large exposure counter. The reason for the counter in this location is not clear, however it might have been a design remnant from the original Kwanon who had both the exposure counter and film advance knob in this same location. The Zeiss-Ikon Contax I also has a similar exposure counter and film advance knob so it’s very possible the Canon took it’s inspiration from that.

From the back we see the arrangement of the rangefinder and pop up viewfinder eyepieces. Although at an upward angle, they’re close enough to not cause a great deal of parallax error. A button to the right of the rangefinder eyepiece is the release for the viewfinder.

In the center of the door is a round piece of metal, which Peter Dechert refers to as the “focus adjustment plug”. He says that these plugs existed on all Canons prior to the S-II, and were used to see through the back of the camera to confirm correct focus on the lens. He does not however, explain how it works as it has no notch or any way to grip it from the back. In order to see through the camera, you’d also need a hole in the pressure plate, which on a bottom loading camera, you wouldn’t normally have access to. I also don’t see how to get this plug off from the back, suggesting that perhaps you need to remove it from within the inside of the lens mount, with the shutter held open, probably in Bulb mode.

Flip the camera over and the Canon is a pretty typical bottom loader. A rotating key both unlocks the bottom plate for removal, but with a reloadable metal film cassette, it also closes it, to protect the film inside when the bottom plate is off.

On the opposite side is a 3/8″ tripod socket, which is larger than the 1/4″ sockets used today. Also notice that the location of the tripod socket is in a metal circle that is symmetrical to the locking key on the other side as the original Kwanons had locking keys on both sides.

Remove the bottom plate and the you can see the film compartment. As with all bottom loaders, in order to load film, you must extend the length of the leader to about 10cm in order for the top row of film perforations to not get snagged when dropping it into the camera. Not shown in this picture is the camera’s body serial number, which is stamped into the under side of the bottom plate.

Both the lens and lens mount are 100% designed and built by Nippon Kogaku. The collapsible 5cm f/3.5 Nikkor is a 4-element design with uncoated optics. Like most collapsible lenses of it’s day, it must be extended and given a small twist to lock it into position before making any exposures. There is no shutter lock connected to the lens, so the shutter will fire if the lens is retracted.

The lens mount is very similar to, but not the same as the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and the mount Nippon Kogaku would later use for the Nikon rangefinder. For starters, there is no external bayonet, and the geared focus wheel is on the outer perimeter of the mount, rather than the top plate of the camera. A focusing scale is engraved in meters from 1 to infinity. According to Peter Dechert, the alignment of this focusing scale changed as the lens mount was revised. This was done to accommodate changes in optional faster lenses like the f/2 Nikkor developed for the Canon.

One of the biggest benefits to the Canon’s pop up viewfinder is that it was physically larger than the through the body ones on Leicas and true Leica copies. This would have allowed people with poor vision or wearing prescription glasses an easier ability to see through it.

Although I was not able to shoot any film through the Canon, my guess is that had I been able to, the images it would have made would have been excellent.

Nippon Kogaku had been making lenses with excellent optical qualities far before David Douglas Duncan “discovered” them in 1950. According to Peter Dechert, the Nikkor 5cm f/4.5 lens seen here was well regarded for it’s sharpness, suggesting that despite being a slower lens, it was optically excellent.

Despite this camera’s age, the build quality was excellent. Canon rose to the top of the Japanese camera industry for their quality control and attention to detail. This is a well made camera with several meaningful updates to the original Leica formula.

I can’t say I love the lens mount, but knowing I understand why they had to change it. I have enjoyed my time with several later Canons, and if I ever get a chance to shoot a working Hansa or Original Canon, I am certain it will be just as good of a shooter.

With prices for Hansa and Original Canons crossing the $10,000 mark, it’s unlikely I’ll own my own, so I guess I’ll just have to cross my fingers that another loaner comes my way allowing me more time to shoot some film in one!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

When I hit the jackpot.. maybe I would choose another source, however…

https://page.auctions.yahoo.co.jp/jp/auction/o454505540

I agree, too rich for my blood. That price is actually reasonable though, as asking prices on eBay are over $10k!!

So, Mike … does Von Cabbage have a Zunow SLR?

His collection is probably over 2000 cameras and in 5 hours I was there, I didn’t see everything. While I wouldn’t be surprised if he had a Zunow, I don’t recall seeing one and I definitely didn’t photograph that. I will have more reviews later this year of some other super cool cameras that I did get to handle!

Thanks for this insightful and informative article, Mike. This is such a rare camera that it has been educational reading about it. What a great pity you couldn’t show us any images demonstratng the lens, even if this was only via an adapter on a digital camera. I’m guessing that the owner was concerned about the mechanical aspects of the shutter far more than the lens, so didn’t want to risk it.

I’d say that you are spot on with your Zeiss comparison with the shutter/film advance knob idea on the front being lifted from a Zeiss Contax which preceded the Canon by a few years and which to my limited knowledge wasn’t used by anyone else. However, whilst similar to the Contax, the Canon is a film advance/frame counter only as the shutter speeds are clearly more usually placed on a top of body dial followed by most cameras, whereas the Contax is a film advance/shutter setting combo with the frame counter in the more usual position on the top right of the body.

I’m guessing that Canon didn’t need the full implementation of the Contax winder as it didn’t incorporate a vertical shutter.