This is a Corfield Periflex 3, an innovative 35mm reflex camera produced by K.G. Corfield Ltd., of Wolverhampton, England between the years 1957 and 1960. The Periflex 3 was part of a series of cameras that use a small reflex mirror and focusing prism mounted to a mechanism that can be lowered directly into the path of the film plane to “see” focus. Like a submarine periscope, it is raised at the moment of exposure to prevent it from blocking light entering the film gate, and lowered again the next time the film advance is operated. The small periscope allows for SLR convenience in a camera with a body no larger than that of a rangefinder. The Periflex 3 uses the M39 Leica Thread mount and can accept most lenses made for it, making the Periflex the rare reflex camera that can use rangefinder lenses without any compromise.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/1.9 Corfield Lumax coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: M39 Screw (Leica Thread Mount)

Focus: 2 feet to Infinity, (unmarked minimum focus distance is actually 9 inches)

Viewfinder: Periscopic Reflex Prism and Separate Viewfinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 736 grams (w/ lens), 576 grams (body only)

Manual: https://cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/cornfield_periflex_ii_iii.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Corfield Periflex series was an innovative approach to building a Leica copy. Focusing is done using a collapsible reflex mirror in the film plane which allows the user to focus like an SLR, but in a body the size of a rangefinder. The Periflex 3 is one of the higher featured models with adjustable viewfinder lenses that can alter the focal length of the viewfinder when using lenses other than 50mm. The Corfield Periflex 3 is a rare example of a camera that’s just as fun to use as it is innovative, plus as an added bonus, it makes really great pictures too! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.0 | ||||||

History

The name Corfield comes from that of it’s founders, Kenneth (later Sir Kenneth) Corfield, and his younger brother John.

Kenneth George Corfield was born on January 27, 1924 in Rushall near Walsall, England and became interested in photography at a young age after being given a Kodak Brownie box camera. As a teenager, he taught himself how to be a photographer and at the age of 16 had won first prize in a contest for the Walsall Photographic Society to which he was a member.

Inspired by his grandfather who was an iron worker, Corfield attended Wolverhampton and Staffordshire College of Technology where he studied mechanical engineering. While attending university, Corfield worked for a local company called Fischer Bearings where he started as an apprentice, but eventually moved up within the company.

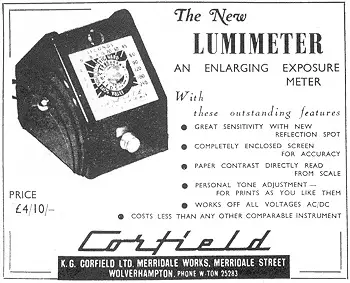

In 1947, now living in Wolverhampton, Corfield read an article describing a new way to measure exposure in film enlargers in which accurate measurement could be taken on the film negative by reflecting light off it from a light source. The article was only written as a proof of concept, but with his interest in photography and his skills as an engineer, Corfield got started on building a prototype.

Corfield made quick work of his prototype and eventually had a working prototype that he demonstrated in a lecture he was giving at a Walsall Photographic Society meeting. Seeing his prototype, several members of the audience were excited about the potential of this new type of meter, and soon after Corfield received an offer to build the device for an unnamed photographic supplies company.

Realizing that he had something that people would pay money for, rather than sell his design to someone else, Corfield decided to build it himself. Taking feedback from his initial prototype, Kenneth Corfield went back to the drawing board and completely redesigned a better version of his meter, and six months later, with help from his younger brother John, had produced 12 copies.

Like his older brother, John Corfield also had a degree in engineering, but was more interested in art design than mechanics. Between the two Kenneth was the designer, and John was the artist.

Each of the first 12 copies of what was now called “The Corfield Lumimeter”, were given away to local photographic retailers in the hope that they would generate sales leads. The first retailer to offer the Lumimeter for sale was R.G. Lewis, one of England’s leading photographic dealers. Lewis ordered 250 Lumimeters and offered them for sale in late 1948 with a retail price of £4.10s.

The Lumimeters sold well, and soon orders were piling in from other retailers. Kenneth, his wife Betty, and John worked day and night assembling new meters, but they could not keep up with demand. Seeing that there was a lot of potential for future sales of this, and other photographic products, first John, and then later Kenneth left their day jobs to pursue Corfield products full time.

Later in 1949, K.G. Corfield Ltd was founded, first to produce Lumimeters full time, with the company eventually expanding to telemeters, optical exposure meters, and eventually a radically redesigned Lumimeter MK2 that was simpler, and much easier to use. By 1952, Corfield had a full range of photographic products for sale under their own name, but they were also regional distributors for Ihagee Exakta, and Leidolf Leidox cameras.

Business was strong, but Kenneth wasn’t content to just produce photographic accessories and distribute other people’s cameras, he wanted one of his own. His first idea was to create a subminiature camera that used 16mm camera as no such model was easily available in England, but the reality of creating an all new camera that likely would have limited appeal quickly put that idea to rest.

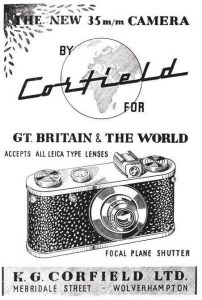

In the early 1950s, the German Leica camera was very popular in England, but import restrictions with Germany made getting new cameras very difficult, and for the few that were available, they were very expensive. Kenneth Corfield, seeing a potential market for a British made Leica camera that could accept Leica lenses, but would be sold at a more affordable price, began work on a new 35mm camera.

Corfield’s initial idea for his new camera was not very ambitious. His only requirements for the camera was that it could accept Leica lenses, used 35mm film, and had a focal plane shutter. The thought was that the camera would appeal to anyone who couldn’t afford to buy into the Leica system, or perhaps already had one, but wanted a second camera.

Early development of the new camera happened quickly, with the body and focal plane shutter being completed first. A lot of the decisions that went into the camera’s design were done in the interest of keeping costs down. Body pieces were made of aluminum rather than brass which was the norm for German cameras. The shutter would be a simple focal plane type with rubberized cloth curtains and speeds from 1/30 to 1/1000. The film transport was simpler than the one in the Leica as it did not use any sort of sprockets to count perforations on the film. This meant that less parts were needed for the film transport, but would have the negative effect of having inconsistent spacing between frames.

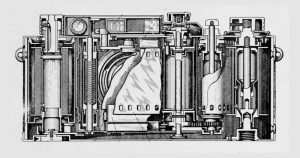

One final change to the new camera from anything previous was in the viewfinder. Rather than use an optical rangefinder, Kenneth Corfield decided on a new type of reflex finder that would rely on a small mirror that could be raised and lowered into the film plane to “see focus” like in a 35mm SLR. The advantage to this design is that the user would have through the lens focus accuracy, but without needing a full sized reflex mirror, the thickness of the camera from the lens mount to the focal plane would remain unchanged. This new viewfinder worked very much like an upside down periscope from a submarine and was where it got it’s name from.

When the first prototypes were completed, the camera was so good, Kenneth no longer saw it as an inexpensive alternative to a Leica, but rather wanted to offer it with it’s own lenses to compete directly with other German cameras. In order to do this, he would need a lens for it.

Since the decision to make a lens came after the camera was already built, Corfield knew that they couldn’t afford to waste too much time coming up with a lens design. In a fortunate coincidence, Kenneth Corfield met an optician named Frederick Archenhold, who worked for the British Optical Lens Company (BOLCO)in Walsall. Archenhold explained that his company had just upgraded their lens making equipment and needed a new product to work on, so both companies were a perfect match as they each had a need the other could meet. Corfield would produce the metal body of the lens, and BOLCO would make the optical glass. When it was completed, the lens was given the name Lumar.

Development of both the Corfield camera and Lumar lens happened very quickly. With the upcoming coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953, immense national pride was sweeping the nation and many British companies were quick to take advantage of the hoopla. Seeing the coronation as the perfect time to launch an all new Made in England 35mm camera that could compete with the Leica, Kenneth Corfield knew that he had to act quickly.

Despite the camera and lens not completely ready for sale, in January 1953, he advertised his new camera with a sketch of the camera, sans periscope viewfinder, and a crude representation of the Lumar lens. In the January 1953 advertisement, the camera was not yet called the Periflex, rather simply a new 35mm camera by Corfield for Great Britain and the World. The only features mentioned were that it accepted all Leica type lenses and had a focal plane shutter.

Later that spring, in May 1953, a more in depth announcement was published, more accurately describing the camera with it’s periscopic viewfinder, body design, and prices. The new camera sold body only for £19.19.6d, with uncoated 50mm f3.5 Lumar lens, £29.18s.6d, or coated £32.19s.6d.

Immediately after the May announcement, orders came pouring in for the camera. Corfield’s expectation that the release of the camera around the Queen’s coronation was accurate, however he underestimated how popular it would be. At the time, the Corfield factory was only capable of producing 25 to 30 cameras per week, but that would eventually increase as the company grew and new workers were hired and trained.

The first Corfield Periflex cameras had black painted top and bottom plates, chrome knobs and lens, and a brown pigskin body covering. The unusual look for the camera certainly made it stand out, but proved to be unpopular both because the soft pigskin leather did not wear well, but most likely because people thought it looked weird.

In the first few years after the Periflex’s release, the camera was refined, with several cosmetic and operational improvements made to give the camera a more normal black on chrome body. The company grew both in size and in the number of employees. Corfield still produced photographic accessories and distributed a number of other products, but the Periflex was it’s flagship product.

By 1956, the unfavorable trade restrictions with Germany that kept prices of imported cameras high started to disappear, meaning that photographers now had better access to improved German, and eventual Japanese designs. As a result, Corfield got to work on an updated Periscope.

The first change to what would eventually become the Periflex 3 was a redesigned automatic periscope. On the older camera, the photographer had to manually raise and lower the viewfinder in between each shot. In the new camera, this action would be coupled to the film advance and shutter release. To accommodate the more complex mechanism for the new viewfinder, the top plate was raised and a through the body viewfinder was added to the camera.

Improvements to the film advance were made too, with a larger and faster film advance knob that could complete the entire process of advancing the film, cocking the shutter, lowering the periscope, and advancing the exposure counter in just a half a turn. The shutter was improved as well, with slow speeds down to 1 second were added, as was full M and X flash synchronization, and a relocated shutter speed dial underneath the rewind knob.

Although the same M39 Leica Thread Mount was retained, a new standard lens was offered on the Periflex 3. The lens was a 4-element 45mm f/2.8 Lumax which was produced for Corfield by Enna Werke in München, Germany. Other German made lenses were released at this time including a faster 45mm f/1.9 Lumax, a wide angle 35mm f/3.5 Lumax, and a telephoto 100mm f/4 Lumar.

Parallel with the creation of the Periflex 3 was a lower cost model called the Periflex 2 that limited the shutter speed to 1/500, lacked a film reminder window, and had a simpler viewfinder. Although both cameras were developed at the same time, the higher end Periflex 3 was released first, with the Periflex 2 almost a year later. The thought was that if the less expensive model were to come first, excitement would die down for the more expensive model and it would be harder to sell.

The Periflex 3 was released in April 1957, and with the 45mm f2.8 Lumax lens, it sold for £79.6s. Production on the original Periflex continued for about a year after the Periflex 3 went on sale, but stopped when the Periflex 2 was released in early 1958.

With the release of both the Periflex 2 and 3, things were looking up for the company, but later in 1958, Corfield got the unfortunate news from the Wolverhampton city council was that their factory was no longer suitable for business and would be condemned. The company needed to vacate the premises quickly and move their entire operations elsewhere.

The search began for a new location, but finding a suitable solution that would not only meet the company’s needs, but was in a location that most of the company’s workers would be willing to relocate to was a challenge. Eventually, a factory in Ballymoney, Northern Ireland was found and in January 1959, Corfield relocated to the new location. Financial assistance was offered to both employees willing to relocate and those who stayed behind. Generous grants by the Northern Ireland government helped with this as Corfield likely wouldn’t have been able to afford it on it’s own.

With operations up and running in Northern Ireland, Corfield announced an update to their flagship Periflex 3. The new model, called the Periflex 3a had updated styling, a film advance lever, removed the strange in-body film reminder window, and the main viewing screen was given a split image focusing rangefinder, similar to other 35mm SLRs of the era.

Over the next few years, updates to the Periflex line continued with simpler models like the Periflex Gold Star, an all black Periflex 3b, and a new series of inexpensive cameras called the Corfield Interplan.

Three Interplan models were created, called models A, B, and C. At a glance, the cameras look very similar to a regular Periflex, but without the periscopic viewfinder, hence the reason for the name change. Each of the three Interplan models were basically the same, with the only difference being the lens mount. The Model A retained the same 39mm Leica Thread Mount of Periflex models, but the Model B used the M42 screw mount, and the Model C had an Ihagee Exakta mount, making each model appealing as a second or third camera for SLR photographers of the day.

Despite Corfield’s early success and excellent timing of national pride, by the start of the 1960s, competition from German and Japanese camera makers meant that new models were being released constantly. The rapid industrialization of Japan meant that the prices of competing cameras kept dropping, making it harder and harder to justify the expense of making cameras like the Periflex. A few attempts at expanding their product lines with an inexpensive point and shoot Corfield Maxim model, and a medium format 6×6 SLR called the Corfield 66 did not help boost the company’s profits.

Strangely, a partnership with the Irish beer company Guinness allowed Corfield to continue producing cameras for a bit longer, in exchange for producing components for new metal kegs used by the brewery. Corfield would expand into other product lines outside of photography as well, even including automobile alternators as a product that they sold for a period of time. The company would limp through the rest of the decade, but by July 1971 could no longer remain viable and would go out of business.

In the years that would follow, John Corfield would take a position as CEO of a company that produced aircraft components, and Kenneth Corfield continued his work in the industrial sector working for a variety of companies. In 1980, he was awarded a knighthood, making him Sir Kenneth Corfield for his positive impact on the Northern Ireland manufacturing industry.

Today, not many people think of Wolverhampton, England or Ballymoney, Northern Ireland as hubs of the camera producing industry, but for a brief moment in time, some of the most innovative and well built cameras were coming from there. For those who lived in those areas at that time, they likely have very fond memories of Corfield and it’s products. As collector’s items, there was no other mass produced camera with a periscope viewfinder like the Periflex, and the fact that you could have through the lens focusing in a body that accepted Leica Thread Mount lenses was quite special.

All Corfield Periflex models are worth adding to your collection, and if found in good working condition, are worth shooting. Prices on them can vary wildly, especially in the United States where they don’t often show up, but if you ever have an opportunity to pick one up for anything close to a reasonable cost, you should definitely consider it.

My Thoughts

Without knowing much about it, a camera called the Corfield Periflex made in England, using an M39 screw mount sounds like an interesting camera. But once you learn what “Peri” in “Periflex” actually means, this camera gets moved to the head of the list of cameras I wanted to review.

It would take me well over a year to find one in good enough and working condition at a price I was willing to pay, but when I finally got my hands on this Corfield Periflex 3, I couldn’t wait to run some film through it.

The Periflex 3 is an interesting looking camera. With rounded edges and a rather tall top plate, the camera bears a strong resemblance to a FED 3 rangefinder. If you were not familiar with this camera, you’d be forgiven if you assumed it was just another Leica rangefinder copy that evolved away from the original design into this.

The truth is, the Perflex does have some Leica DNA in it, as it uses the same lens mount and appears to have an identical flange focal distance. Beyond though the cameras are quite different.

With the Lumax f/1.9 lens mounted, the camera weighs a reasonable 736 grams without film loaded. The matte finish chrome plating has held up well and the general build quality seems good, but this example had badly peeling leather that I eventually replaced myself.

Looking at the top of the camera, from left to right, you have the combined shutter speed dial with speeds from 1 to 1/1000 plus some kind of rudimentary EV calculator. I say rudimentary as there does not appear to be any way to adjust for film speed as the inner numbers do not move. Playing with the knob, if I line up EV 15 and f/16, the shutter speed dial is halfway between 1/60 and 1/125, possibly suggesting the scale is calibrated only for ASA 100 speed film. The Periflex 3 manual offers no additional help, merely saying to set the shutter speed to an appropriate setting and then take a reading with an exposure meter.

In the center is an accessory shoe for a flash or auxiliary viewfinder or rangefinder. Engraved behind the shoe is the camera’s serial number and to the right, a small rewind release button for when you reach the end of a roll of film.

Off to the right, is the large combined film advance knob and exposure counter. The exposure counter is subtractive, showing how many exposures remain on the roll and must be manually reset after loading in each new roll of film. The gearing on the film advance knob is quite high, only requiring a half turn to advance the film to the next exposure, drop the periscope into the film plane, and cock the shutter. Corfield promoted this as some kind of early rapid film advance as it could be done quickly with a single twist of the wrist. In reality, the high gearing requires quite a bit of effort, especially with film loaded into the camera.

The most interesting thing on the back of the camera are the three openings for the main viewfinder, periscope viewfinder, and perhaps the camera’s most unusual and if I’m being honest, most useless feature, which is a film type reminder window. I’ll explain more about how these three windows work later in this review, but otherwise there’s nothing else to see on the back of the camera.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located 3/8″ tripod socket, which this example has a 1/4″ adapter already screwed in it, likely put there by some previous owner who wanted to use it on a modern tripod. To the left of the socket is the film door release, which requires you to press and rotate until a black triangle on the lock lines up with a black dot on the bottom plate.

After unlocking the film door, the entire back and bottom of the camera slides off. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed, and single slotted take up drum. On the inside of the film door is a glass pressure plate which is held in place by a piece of yellow foam. On my example, the foam was still soft and held the pressure plate in it’s correction position, but this is something you’d likely want to check on any Periflexes you come across.

The Periflex is a bit different from other 35mm cameras of the era in that it does not have any sort of geared sprocket shaft for counting exposures. Each turn of the film advance knob rotates the drum exactly 180 degrees which means that half of the time, the slot for the film leader is facing away from you, so you can only attach a new film leader every other turn of the film advance.

Another oddity of this design is that as film wraps around itself on the drum, the outer diameter of the film increases causing later exposures on a roll of a film to travel farther than at the beginning of the roll causing inconsistent frame spacing between images.

In the image to the right, I show the exact same roll of film shot in the Periflex, with the beginning on the left and the end on the right. Notice how the spacing looks pretty normal on the left and progressively gets wider near the end. This wasted film will decrease the number of exposures possible on a roll of film by 1-2 and would likely drive a film processor nuts when trying to cut the film, or mount it into slides.

The side profile of the camera shows the thickness of the body and the depth of the Lumax lens. Compared to a screw mount Leica, the Periflex is about 1-2mm wider.

Both sides of the camera have metal strap lugs which is a nice feature as many cameras of this era required the original leather case to be used with a neck strap.

The Periflex uses the same M39 screw mount as the original Leica rangefinders, along with every German, Japanese, and Soviet copies. Although the Perifiex lacks a rangefinder, you can use most Leica Thread Mount lenses with the exception of those like the Jupiter-12 which protrude into the film box as they would make contact with the periscope. Corfield foresaw this problem and put baffles inside the mount which would prevent you from fully mounting these lenses.

Using screw mount lenses on the Periflex was likely a huge selling point for Corfield as people would be more likely to consider a new type of camera made by an unfamiliar English camera company, if they knew they could use their existing Zeiss or Leitz lenses on them.

You can even use the Periflex’s Lumax lens on rangefinder cameras as well, except it doesn’t couple with the rangefinder. The lens will mount and work correctly, but you’ll have to scale focus the lens by guessing distance or using an external rangefinder.

Above and to the left of the lens mount is the front shutter release button. The Periflex would normally have a metal shroud around the button that can be unscrewed, revealing external threads allowing you to attach Leica-style shutter release cables. I found this shroud to be uncomfortable for my fingers, requiring too much of a sharp angle for my finger to comfortably fire the shutter, so for most of the time I used the Periflex, I removed this piece.

Above and to the right of the shutter release is what I referred to earlier in this review as the Periflex’s most useless feature which the manual refers to as the film memory window. When looking through the round window all the way to the right on the back of the camera, you can see a small scale of numbers which on my example, do not match what the manual describes.

From the Periflex 3 manual, it says there should be two sets of numbers, one gray that goes from 10 to 500 and a second set in orange from 10 to 80. In the image to the right, what I see are clear numbers on a black background from 20 to 23, which might be DIN numbers, but they never seem to change. A small knurled dial on the front face of the camera is used to change these numbers, but on my example, don’t do anything suggesting this feature is defective on mine.

One final clever feature of the Periflex is that since it uses an interchangeable lens mount and the user may want to use wider or longer focal lengths than the standard 45mm Lumax, the front viewfinder window has an optical piece of glass that can be unscrewed and replaced with ones for different focal lengths. This is a really nice feature as it means you can use the same viewfinder for all focal lengths, as long as you have that piece. Lose it however, and you’re back to using auxiliary viewfinders for lenses other than 4.5cm.

When this camera was current, buying a lens with a focal length other than 45mm would also include this extra piece which mounts in front of the viewfinder window, altering the focal length of the viewfinder. Lenses ranging from the 35mm Retro-Lumax to the 135mm Tele-Lumax were offered, and when used with the correct auxiliary viewfinders would allow the proper focal length to be seen through the viewfinder, eliminating the need for an auxiliary viewfinder.

Corfield Periflex 2 and 3a: A lower cost version called the Periflex 2 was also available which lacked both the film memory window and interchangeable viewfinder lenses. The later Periflex 3a retained the interchangeable viewfinder lenses, but also did away with the film memory window.

Both the Lumax 45mm f/1.9 and Retro-Lumax 35mm f/3.5 lenses have a somewhat hidden feature in that they offer close focus at distances down to 9 and 6 inches, respectively. The focusing scales engraved into each lens strangely do not show distances closer than 2 feet however, but turning the lens beyond the 2 foot mark allows it to extend out approximately 10 extra millimeters, allowing for close focus. Macro focus on rangefinder cameras is difficult as most optical rangefinders cannot accurately focus closer than 3 feet, using the Periflex’s ground glass periscope allows you to see sharp focus through the lens with ease.

Both the focus and aperture rings are covered in leather for a soft touch experience, and a depth of field scale is also present.

So far, most of the Periflex’s operation isn’t that different from other mid 20th century rangefinders. Except this isn’t a mid 20th century rangefinder. The signature feature of the Periflex is it’s periscopic viewfinder which is both similar to rangefinder cameras like the Leica in which the rangefinder is in a separate window from the main viewfinder, but also a central focusing aide on an SLR.

On the back of the camera are three windows. The third isn’t part of the viewfinder at all, and is a strange optical film reminder dial, that on mine appeared to be broken. This feature only exists on the Periflex 3 as it was left off the Periflex 2 and omitted on the Periflex 3a.

The other two windows however are the most important. Like the Leica, you compose your image using the window on the left (the Leica’s is on the right). This window has etched frame lines to approximate the 4.5cm lens that is attached and parallax hash marks to be used for close focus. The Periflex 3 has a removable front piece for the viewfinder which alters the focal length of the viewfinder when using lenses of other focal lengths.

The right window looks through the periscope behind the lens mount. With earlier Periflexes, you had to manually raise and lower the periscope, but with the Periflex 2 and 3, this action is coupled to the film transport. Advancing the film to the next exposure also lowers the periscope in one motion. Pressing the shutter release will first raise the periscope before firing the shutter.

Watch the short video below showing the sequence of the mirror raising moments before the focal plane shutter fires.

A small square piece of ground glass is used to focus your image exactly how you would on an SLR with a waist level finder. Since there is no pentaprism, the image is reversed left to right, but otherwise works like any other SLR. The ground glass is in the same exact location as the film plane, so your image moves in and out of focus from infinity, all the way to whatever the minimum focus distance is on the lens mounted to the camera. With the 4.5cm f/1.9 Lumax I have mounted, the minimum focus distance is an incredible 9 inches, far shorter than that of any M39 rangefinder camera ever made! Swap out the Lumax lens with any other M39 lens that fits, whether its a Canon, Leitz, or KMZ Jupiter, and you can get accurate focus, regardless of focal length.

The image through the periscope is small, covering roughly the center 25% of the total exposed image. While this might seem small at first, if you consider that the split image or microprism focus aides found on most SLRs also only cover the center of the exposed image too, you quickly realize that focusing on the Periflex is not that much different from a real SLR.

One last thing to keep in mind is that the Periflex does not have an automatic diaphragm, which means you must manually open the lens to it’s widest setting to allow the maximum amount of light through the periscope for focusing. If you try to do it with the lens stopped down, it gets dark very quickly.

The image above is a composite of the three windows. You cannot actually see all three at once, but individually, you can see the viewfinder window with the normal 4.5cm lens attached, the periscope focus image which is reversed left to right, and finally, the rather useless film reminder dial, which on my example, only shows DIN numbers. According to the manual, ASA speeds should be there too.

As a whole, the Corfield Periflex 3 is a very interesting camera. It truly is equal parts rangefinder and SLR, all wrapped up in one easy to use package, and with the 4.5cm f/1.9 Lumax lens, it should be capable of excellent images. Although getting used to the tiny ground glass window does take a little bit of time, I found it’s learning curve to be pretty short. I felt comfortable shooting the camera before I ever finished my first roll.

It’s a shame more companies didn’t use the periscopic viewfinder like this, but I guess they didn’t need to as the rise of the SLR happened rather quickly, meaning that a hybrid system like this wasn’t necessary, but for the narrow window of time the Periflex was a ground breaking design, it definitely was cool, but what kinds of images doe it make?

My Results

When this Periflex arrived, it was very stiff. Turning the advance knob took a lot of effort, and the sounds of the shutter cocking and the periscopic viewfinder lowering into position were unlike that of any other camera. You can definitely feel all the metal pieces moving, and with the stiffness, I was fearful I might break something. Thankfully, after a small amount of exercise, the camera loosened up quite a bit. Now with the camera appearing to work, I didn’t want to waste any time shooting it.

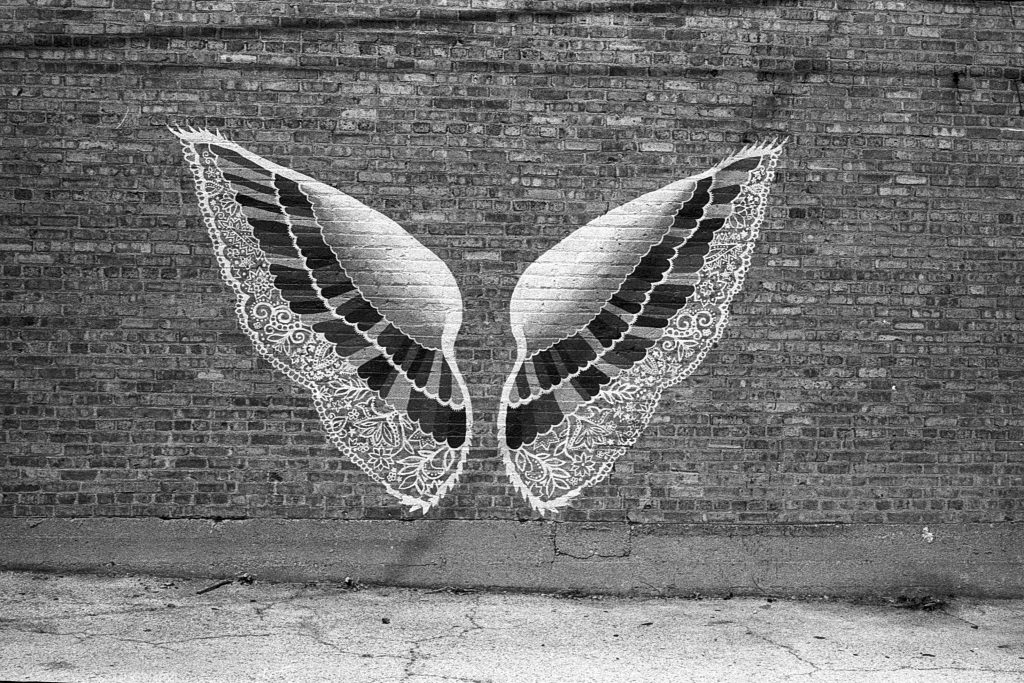

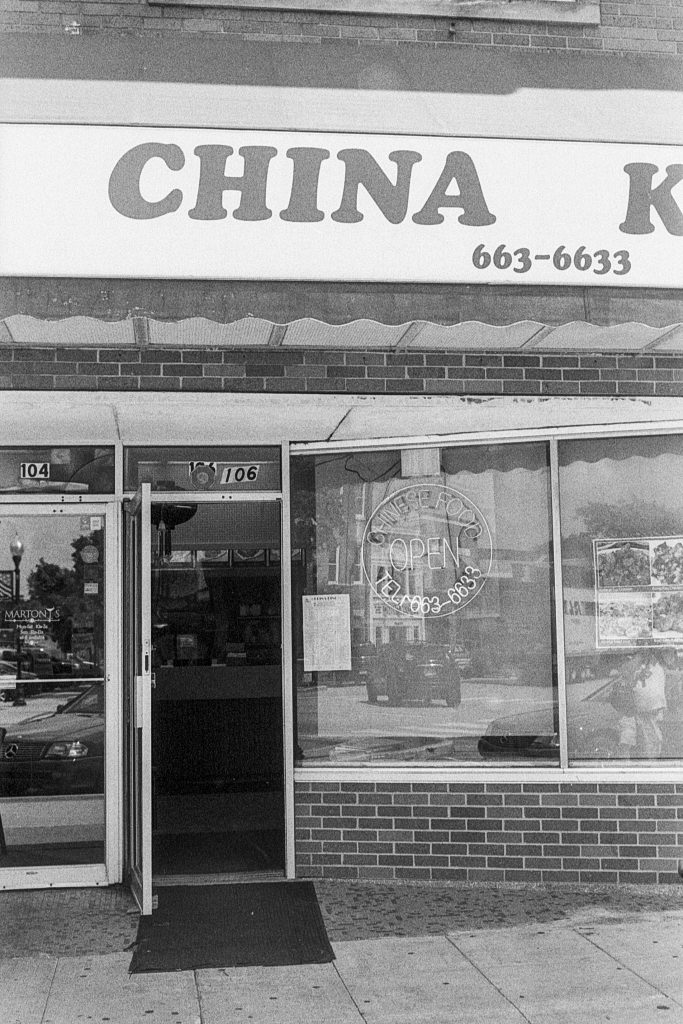

For the first roll of film in the Periflex, I went with some expired bulk Kodak Plus-X 125. I had been shooting a lot of TMax 100 lately and wanted to mix it up, and having seen good results from this film in my review for the Kemper Kombi, I loaded up a cassette and shot it on a nice sunny summer day in Crown Point, Indiana.

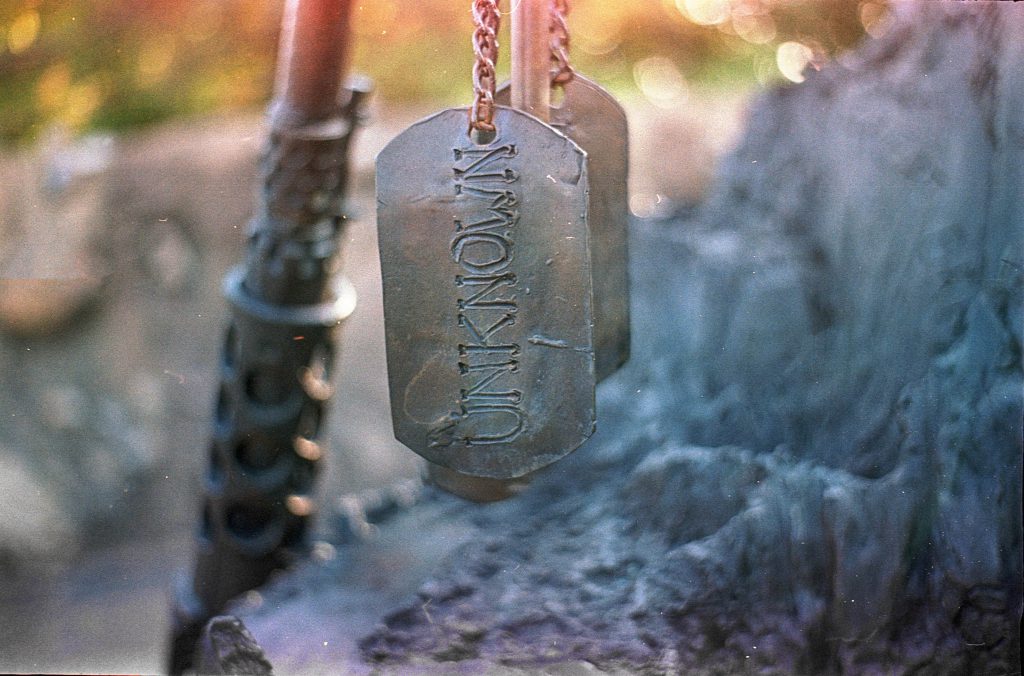

Pleased with the results from that first roll, I figured I would tempt fate again and loaded in a second roll. With fresh supplies of color film dwindling, I tapped into a large bag full of 15+ year expired Kodak Gold 100 and shot it around Halloween 2021. I’ve shot this film before and although I found that it still exposes close to box speed, I expected to see dramatic color shifts and some degradation near the edges.

Not really knowing how well the camera worked after loading in that first roll, I was apprehensive as I was taking the Kodak Plus-X out of the Paterson tank. When I got my first look at the wet film, I saw what looked to be properly exposed images that to the naked eye looked like they were properly in focus.

After scanning the film into my computer and getting a better look at them, I was quite pleased at the quality of the images the German Lumax lens produced. Enna Werke in München, West Germany made these lenses, and although they were a respected optics maker in their day, they never reached the level of respect of companies like Carl Zeiss or Schneider-Kreuznach.

Looking at the images from both galleries, image sharpness is excellent corner to corner. I see only the tiniest bit of softness in the extreme corners and no noticeable vignetting which would be characteristic of a Tessar or some other kind of lesser lens.

I can’t speak with absolute certainty of the color rendition as my only roll was with expired Kodak Gold 100, but I’ve shot this film before, and the results here seem consistent with how the film looked in other cameras, so I have to imagine that the blue lens coating on the Lumax does as good of a job as any out there. I am certain I’ll shoot this camera again and hopefully I’ll have some fresh color film to put through it, and when I do, I’ll be sure to come back here to update this review.

I genuinely liked the entire experience using the Periflex. Aside from the stiffness that I am certain is a result of age, and the erratic frame spacing on the film, everything else about the camera is a joy to use. The periscopic viewfinder works incredibly well. In the history section above, I described that the original plan with this camera was to produce a low cost alternative to the Leica that was made in the UK, but when Kenneth Corfield saw the first prototypes, he was so impressed with it, he changed his position and now saw it as a direct competitor to the camera. I think this was a fair assessment as the Periflex is a very well built camera with a great lens.

As with most cameras of this age, condition is everything. This is the only Corfield Periflex I have ever handled, so I cannot say whether my experience is common with others out there, or if I just got really lucky with such a fine working example, but I can tell you that when found in good operational condition, these are a a joy to use.

I find that when shooting vintage cameras, some are unappealing as they are too difficult to use, and others are unappealing because they are too boring to use, but the Corfield Periflex is very appealing as it has a distinct operation with a feature not found on any camera, yet it’s intuitive and fast to use, while managing to produce excellent results.

I genuinely love this camera and will definitely keep it in my permanent collection. That said, these are not common cameras, especially in the US, so finding one might be difficult for anyone reading this review, but if one ever comes your way, and you’re reasonably certain it works, then you definitely owe it to yourself to give it a chance!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Periflex

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/other/periflex.html

http://www.griffinfilmworks.com/#!articles.periflex_1

https://cameracollector.proboards.com/thread/7441/corfield-periflex

http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/Museum/CorfieldCameras/corfield.htm

Thank you for this detailed history of both the cameras and the men who designed them. Do I understand that the flange focal distance on the Periflex is within 1mm of that of a Leica or Canon rangefinder? So that one could use Leitz and Canon glass on it and get infinity focus?

Roger, as regards Leica lenses, the answer has to be yes, as this was the original intention of Corfield in designing the Periflex.

It’s exactly the same flange focal distance. I own a broken 3a and it focuses my LTM lenses perfectly.

Great review, Mike. My one and only Periflex is the Gold Star, based on the 3a design but with a reduced shutter speed range of 1sec – 1/300 +B. I purchased it, body only, in what is for me a snazzy new body covering, for just £25. Subsequently, I’d hoped to pair it with the f1.9, but prices put paid to this idea! So far, I’ve only added a set of extension tubes. Try doing this with a Leica.

What can’t come across in any camera review is what it feels like in the hand. The rounded ends and the front-mounted inward pushing shutter release make for a very comfortable camera to hold.

I had the Periflex Gold Star too a long while ago it had Corfield’s own branded 50 mm 1:2.8 lens on it; I doubt I paid more that 10 GBP for it back then but sold it in the US in 2016 ago for nearly $100!

As always, your reviews are the best. I’m genuinely in awe of how much information you found regarding Corfield. I’ve been researching the company for quite a while now, yet I was very surprised at the wealth of new things about them that I learned here. Where did you get all this info from? Old magazines?

Andreas, you may as well start here.

http://www.historywebsite.co.uk/Museum/CorfieldCameras/corfield.htm#menu

or

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/other/periflex.html

My second camera was a Goldstar bought used in 1959. I invariably shot Kodachrome and the mounted slides came back with a multitude of little black slithers of film cut from between the frames. I assume Kodak did this automatically. I have since added an orginal Periflex to my collection.