As a collector and blogger, I spend so much of my time researching and writing about cameras from the early to mid 20th century and digging into old photo magazines looking for interesting articles or advertisements about whatever topic I am working on, that sometimes I tend to forget about recent history.

As a collector and blogger, I spend so much of my time researching and writing about cameras from the early to mid 20th century and digging into old photo magazines looking for interesting articles or advertisements about whatever topic I am working on, that sometimes I tend to forget about recent history.

For all that I’ve read up on the various roll film formats and extinct film processes over the years, there’s one format of film that in the 7+ years this site has existed, I have never written about, which is the Advanced Photo System, more commonly called APS or Advantix film. I can list off a bunch of cameras that use 127 and 828 format, or when the first Kodachrome film was made, but I can’t tell you anything from a film format that was conceived, released, and discontinued in my lifetime…and not just in my lifetime, my adult lifetime!

For those of you shooting film in the mid 1990s, you likely remember the announcement of the “next best thing”, the replacement for 35mm film with all these great new benefits.

Coming up with a replacement for Kodak’s Type 135 film which first made it’s debut in 1934 was not unique to APS. Other companies like AGFA tried it twice with Karat and Rapid film, Kodak themselves tried it in 1963 with Type 126 Instamatic film, and again in 1980 with an unreleased prototype 35mm film which offered a large number of improvements, some of which foreshadowed APS.

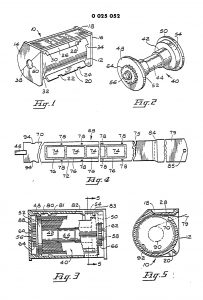

Each time a new format was proposed, a key element to the new film was that it would be easier to load. Both Karat and Rapid films used a cassette to cassette transport that never needed to be rewound and there was no take up spool to attach a leader to. Instamatic was a single plastic cassette that contained both the take up and supply sides, so there was no leader to contend with and you never had to rewind it. Kodak’s 1980 film got rid of the leader and made it easier for the camera to positively locate the end of a roll, eliminating accidental over winding of film which could tear it out of it’s cassette.

But of course, all of these formats eventually failed, with type 135 film continuing to be made.

So, in 1995 when new APS film was announced, people were rightfully skeptical. Not only did everyone from amateurs to professional photographers have a lot of money invested into current 35mm systems, but many of the shortcomings of 35mm had already been overcome with automatic film loading cameras, DX encoding, and those little peep holes in the back door of cameras to see the cassette.

APS was different though. Unlike previous new film formats, it wasn’t being developed by just one company. The specifications of the new film were decided on by a committee of nearly 50 different film and camera companies. Before the first rolls hit store shelves, supplies of APS film were guaranteed by Kodak, Fuji, Konica, and AGFA. Camera models that supported it were coming from Kodak, Minolta, Canon, Fuji, and Nikon. Each of these companies got to discuss and contribute to what they wanted in the new film and how it would work. They also guaranteed launch day support with a variety of new models, giving customers many options on launch day. Surely, with so many industry heavy weights all throwing their support into the new format, it would be a success, right?

Before we talk about the demise of APS film, lets talk about what was good about it and what kinds of growing pains did it experience in it’s first few years. This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings to you a variety of articles all from Popular Photography magazines published in 1995 and 1996 (Modern Photography no longer existed and Herb Keppler worked for Pop Photo by this time).

The most detailed of the articles I found comes from March 1996 and was authored by Herbert Keppler himself. This 8-page article goes over the entire system, promoting many of it’s features, and also shows some sample images and Keppler’s thoughts on a pre-production sample he was given by Kodak.

More compact – The film itself was 24mm wide, allowing the cassette to be smaller and lighter than 35mm in every dimension. Despite being small, the cassette was made from a durable plastic that was said to be resistant to damage, moisture, and possibly, time.

More compact – The film itself was 24mm wide, allowing the cassette to be smaller and lighter than 35mm in every dimension. Despite being small, the cassette was made from a durable plastic that was said to be resistant to damage, moisture, and possibly, time.- Easier to load – With APS, loading a new cassette was done by dropping it into a compartment in the camera without needing to attach a leader to a spool. The film would always be locked inside a plastic cassette when out of the camera, and through an automatic loading system, the camera would open the cassette and pull the film out to expose it, and automatically rewind it at the end of each roll. You could not open an APS camera with film loaded, the door would be locked until after it was rewound. Some cameras would support midroll changes, rewinding the film back into the cassette and recording how many exposures were made, so that the next time the cassette was inserted, it would automatically advance to the next unexposed frame.

- Multiple aspect ratios – Although regular 35mm film exposures usually had an aspect ratio of 24mm x 36mm (with some half, square, and panoramic frame options), most APS cameras would support three distinct aspect ratios, C for classic which is 3×2 (4″x6″ print), H for HDTV which is 16×9 (4″x7″ print), and P for panoramic which is 3×1 (4″x11.5″ print). For the few cameras that didn’t support this feature, different aspect ratios could still be printed by the photofinisher and you could have exposures printed using multiple aspect ratios if you wished.

- Better economy – Because there was no leader, the largest cassettes could hold up to 40 exposures vs 36 for 35mm. Cassettes with 25 and 15 exposures would also be available at a discount.

- Easier to store – Developed APS film was stored in it’s original cassette and returned to you. Since the film is retained in it’s original cassette, it is free of damage from UV light, dust, scratches, and fingerprints. An indicator on the side of each cassette would help you differentiate between a roll that has been developed, exposed but not developed, partially exposed, and unexposed.

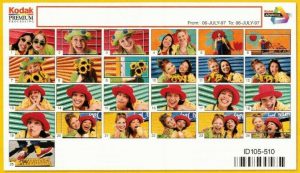

Better organization – Each roll of APS film would automatically include an index print showing what was on that cassette. Also, the film contained a magnetic strip (Called Information eXchange, or IX) next to each image that could record information about each exposure such as date, frame number, exposure information, and in some cases up to 56 characters of custom data that could automatically be printed on the back of each print. The magnetic strip could also indicate how many prints of a single image were desired. With the film still in the camera, you could ask for multiples of a specific frame that when the film was developed, would automatically be printed.

Better organization – Each roll of APS film would automatically include an index print showing what was on that cassette. Also, the film contained a magnetic strip (Called Information eXchange, or IX) next to each image that could record information about each exposure such as date, frame number, exposure information, and in some cases up to 56 characters of custom data that could automatically be printed on the back of each print. The magnetic strip could also indicate how many prints of a single image were desired. With the film still in the camera, you could ask for multiples of a specific frame that when the film was developed, would automatically be printed.- Future expandability – The data contained on the magnetic strip offered the possibility of features in the future such as voice notes, more integration with digital scanners, and possibly even some type of hybrid film/digital features not yet thought of when the film was being developed.

The features of APS film were certainly exciting. Some of the benefits like the ease of loading and protecting the film were better than Instamatic or other proposed alternatives to 35mm film. For anyone not interested in the multiple aspect ratio feature, the default picture size of 16×9 was forward thinking as it would be nearly 10 more years before a widespread adoption of HDTV with the same aspect ratio would hit the market in the US (Japan had them sooner). Plus, the ability to magnetically record digital data next to each frame offered a level of upgradeability for features that could be implemented further down the road.

Things were looking up for APS and many people were rightfully excited, but what went wrong?

Like any new technology, APS film had some growing pains upon it’s release. For starters, established 35mm shooters were skeptical of the new system. The most common knee jerk reaction was that the film had an exposed area of 16.7mm x 30.2mm, which was 71% smaller than the 24mm x 36mm exposures of regular 35mm film. Smaller negatives should result in less detail and grainier images, right?

Keppler was wise to address this point in his introductory article, showing large crops of the same image shot both on ISO 200 speed APS film and using Kodak Royal Gold 200 in a comparable 35mm point and shoot. Looking at the detail of the exposed images, Keppler noted that when looking at 4×6 and even 8×10 prints, images shot on the two films looked equally sharp. It wasn’t until 14×17 enlargements were made where one could see more detail in the 35mm prints.

At the end of his article, Keppler declared that based on this one preproduction sample, APS was already a superior option to 126 Instamatic, 110 Pocket Instamatic, and certainly, Kodak Disc film. He stopped short of saying it would replace 35mm, rather that it would exist as a complement to it.

A second article from January 1996 was also written by Herbert Keppler, but came before any sample cameras could be tested. This article is shorter than the earlier one as it’s more of a technology preview for customers but it gives a bit of history into the format, saying it had been in development for 10 years, first only by Kodak, but that other manufacturers were later brought in to help finish it.

APS would not make it’s retail debut until April 1996. At that time, a small selection of cameras were available from Kodak, Minolta, Nikon, Canon, and Fuji. In their April 1996 issue, Popular Photography featured two articles previewing the cameras being released by those companies, along with a neat APS VCR developed by Fuji, but sold in the US by Minolta as the Vectis Photo Player VP-1.

The VP-1 was a standalone device that could accept developed rolls of APS film and displayed the exposed negatives on a television screen with fancy transitions between images and even adding in some background music, sort of like a modern day slide projector for sharing vacation photos with your friends and family. Other features of the VP-1 would be the ability to reorder the prints and selecting which prints you wanted to make duplicates off. Doing this would rewrite data to the magnetic strip in the cassette so that when sent to a photofinisher, the development machine would automatically know what to do.

One final option, which isn’t explained in any detail, was compatibility with yet another gadget called the Snappy, which for an additional $200 would allow you to plug into a computer’s parallel port, giving you the ability to digitally scan your images into a Windows or Mac computer.

As for the available cameras, as expected, most are of the cheap to midrange point and shoot variety. More advanced SLR models were on their way, but weren’t included in the first models offered. The selection of simpler cameras was wise both in that it allowed a less expensive entry point into the system, simpler cameras are easier to produce, but that there was a limited amount of film available and consumer grade 200 and 400 speed films would appeal to the largest group of users.

Note: APS cameras produce an exposed image smaller than 35mm, similar to how many digital cameras have smaller “crop” sensors. This results in a difference in the advertised focal lengths of the lenses.

A few observations of this initial wave of cameras are:

- Both Kodak and Nikon would release at least one rebranded Minolta in their lineup.

- Nikon would duplicate all of their models with IX capable and non-IX capable versions of the same camera.

- Most cameras have zoom lenses with the exceptions being the Kodak Advantix 3700ix and 3600ix models with a 24mm Tessar style lens, Minolta Vectis UC (and Nikon Mini rebrand) with a 24mm f/4 lens.

Canon would only have one model, the ELPH, but it would be the only camera with a distinctly premium style with an aluminum body and a compact design that takes full advantage of the smaller size of APS.

Canon would only have one model, the ELPH, but it would be the only camera with a distinctly premium style with an aluminum body and a compact design that takes full advantage of the smaller size of APS.- Fuji would release the Endeavor 4000SL which had a “bridge camera” design and 4x 25-100mm lens.

- Both Fuji and Kodak would release single-use APS cameras in their QuickSnap and FunSaver lines. These cameras would not support the full array of APS features, but would benefit from the smaller package and multiple aspect ratio functionality.

By the end of 1996, new APS models from Konica, Olympus, Vivitar, and Yashica joined the available number of cameras available.

What good would new cameras be without film, so along with the models mentioned in the above articles, several different emulsions from Kodak, Fuji, Konica, and AGFA were available at launch with a few others to follow.

By November of 1996, a total of nine different types of films could be purchased with speeds ranging from 100 to 400. Although the APS standard would allow for films in the range of 25 to 3200 to be created, all of the early films, and those to come would remain in that point and shoot friendly 100 to 400 range.

By November of 1996, a total of nine different types of films could be purchased with speeds ranging from 100 to 400. Although the APS standard would allow for films in the range of 25 to 3200 to be created, all of the early films, and those to come would remain in that point and shoot friendly 100 to 400 range.

Also to the dismay of professional and enthusiast photographers (but not entirely unexpected) all APS films were color negative film stocks. No slide film or black and white emulsions were available at launch. Although there was no technical reason why these types of films couldn’t be made, it made the most sense to produce the most common types of film stocks that someone interested in a new type of point and shoot camera would be most likely to buy.

Each of the nine films available were said by each’s respective manufacturer to be improved from comparable 35mm stocks. Seven of the films were totally new emulsions, the only exceptions being the lone Konica 400 film and AGFA’s Futura 100. The film base of all APS films was made of something called polyethylene naphthalate, which is both thinner and stronger than the base used in 35mm film which helps the film lay flatter when being exposed. In addition, the light sensitive emulsions each had improvements, which were said to reduce the grain size, which would help offset the smaller negative of APS compared to 35mm. However much of this “new technology” was marketing fluff is not clear, but based on initial results, including articles like those above, prints as big as 8×10 looked identical in APS compared to 35mm, suggested there were improvements.

The following two page round up of the nine available APS films was printed in the November 1996 issue of Popular Photography magazine.

From the moment the first previews of the new film were made public, there was equal amounts of excitement and trepidation from the photographic world. On one hand, Kodak’s type 135 cassette was well over half a century old so some new features were definitely welcome, but in that half century, 35mm film had entrenched itself as a worthwhile format which for many professional photographers saw no reason to upgrade.

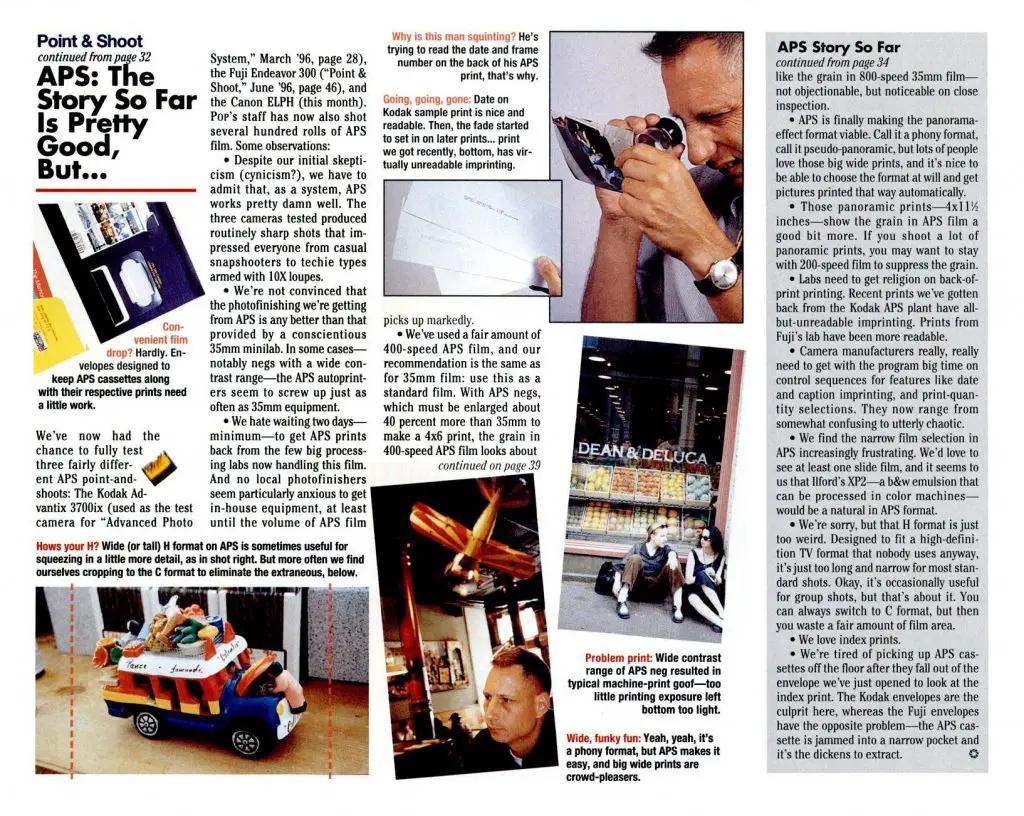

Regardless of which side of the fence you were on, many people took a wait and see approach for the new format, eagerly awaiting some real world testimonials. In the months that followed the April 1996 release of APS, some of it’s flaws became evident. In their October 1996 issue, Popular Photography ran the following short article that went over some of the most prominent concerns of the new format.

- The prevalence of point and shoot models and point and shoot friendly film stocks kept professional photographers away. It was clear from the very beginning, APS was a winner in the lower end of the spectrum, and even the SLR models that did come out, were only comparable to consumer entry level 35mm SLRs, but there was nothing remotely close to the Nikon F-series or Canon EOS line of cameras.

-

Kodak would eventually make a black and white film, but it was a monochrome C41 process. A lack of professional film stocks, slide film, or true black and white film stocks further kept the pros away. While Kodak would eventually release an ASA 400 black and white APS film, it was a monochrome C41 process, similar to BW400CN and not a true black and white film. Fuji would also release an APS E6 slide film in Japan only, but it was never exported to the United States.

- Since APS film required machines and equipment that was incompatible to existing 35mm minilabs, the cost to develop APS film was higher than that of regular 35mm. Furthermore, most film labs charged an additional premium for the panoramic prints, and sometimes even upsold other features like IX data compatibility. In addition to a higher cost, it often took longer for APS film prints to come back because of the extra effort required.

- Despite all of the efforts put into APS to make getting consistent prints back from the lab, the rate of unsatisfactory prints due to incorrect color balance, over, or under exposure was not any better with APS film. Although the technology was there in the IX encoding to indicate proper exposure, and in more advanced cameras, focal points for correct cropping, it seems that the labs doing the work (either through machine or human error) were still learning.

- People weren’t sold on storing the cassettes. One of the biggest improvements of APS over 35mm was that the exposed negatives were stored in the original cassettes, protected from fingerprints, scratches, or other damage, but that required a place to store the round plastic cassettes. It seems that people found it easier to store the flat negatives of 35mm in paper envelops, rather than find a place for the cassettes.

In the small list of cons above, it is likely most of them would have been improved upon, or completely eliminated with future technology. More advanced, finer grain films with more accurate colors would have further improved image quality, slide film and black and white film stocks likely would have been developed, and the labs would have likely gotten better and cheaper at making prints.

APS was clearly a winner in the point and shoot segment. If you were in the market for an easy to use, do everything, consumer grade $100-$400 point and shoot camera, there was almost no reason to stick with 35mm. The APS film format proved it’s ability to be easier to load, more fool proof, and capable of excellent prints.

While we can talk about the reasons the pros didn’t adopt it, their lack of support isn’t what killed APS either.

Without a doubt, the one thing that doomed the entire format was the rise of the digital camera. While digital cameras existed prior to 1996, it would only be a few short years after the release of APS that cameras like the Nikon D1 would hit the market.

In the first five years of the next century, digital cameras would skyrocket in popularity from a futuristic curiosity, to a must have. Sales of film and film cameras would plummet in the years from 2000 through 2004. Even with a much larger market share than APS, regular 35mm film took a hit and it quickly became clear that APS had no chance in the ever increasing digital photographic world.

Despite having innovative technology and a promising first couple of years, in January 2004, Kodak ceded defeat and ended production of all APS cameras. Kodak and Fuji would continue to support existing models by producing a limited amount of APS film, before both exiting the market completely in 2011.

Another loss for APS was that it contributed to the downfall of Minolta who invested the most of any company into the format except for Kodak. While it’s not fair to suggest that APS singlehandedly put the company out of business, the one two punch of the rise of the digital camera and the failure of a system that Minolta heavily invested in, further added to the company’s financial woes. In 2003, Minolta would merge with Konica, another struggling Japanese camera maker, and in 2006 would exit the camera business altogether, liquidating it’s assets to Sony.

To call the Advanced Photo System a complete failure isn’t fair however. The format did nearly everything it had hoped to do. Despite what a lot of people thought, neither Kodak, or any other APS company admitted that the initial intent was to completely replace 35mm. It was pretty clear, even before it’s April 1996 release, that the target customer for this film system was the point and shoot and entry level SLR market. The film looked good, most of the film’s new features performed as expected and even improved upon similar features in existing 35mm models. There was even room for the format to grow.

If there’s one thing APS did wrong, is that it came out too late. Had something like APS been released 10 years sooner, and been given a longer time to gain market acceptance, there’s a chance it could have survived longer. No one really knows for sure, but it’s fair to say that had the digital revolution never happened, or at least took a little longer to catch on, people like me likely would still be shooting fresh stocks of the film and waxing nostalgic on “classic APS” models like the Minolta Vectis S-1 or Nikon Pronea 6i.

Good concise story on this disappearing format. Thanks, Mike! Ironic, Konica Minolta selling their assets to Sony … a company who likely has lost more money on innovative formats that crashed and burned in the marketplace.

Yeah, Sony definitely has a long history of going their own way on formats that didn’t succeed, Betamax, Video Floppy, Mini Disc, SACD, etc.

Mike, Technology often takes no account of the end user. Betamax had superior image quality than VHS, which is why it found support from professionals and which VHS didn’t. But VHS found popularity with the masses because it was cheaper! In the UK a rather unusual situation existed – rental business. Because of cost, most preferred renting recorders than buying them, and rental companies actively promoted VHS machines, often with paired down models to help keep costs down. There were a couple of rental companies with national coverage, so whilst we could get Betamax, it was always at a premium. The other advantage VHS had was longer playing times.

Video floppy fall out of favour was obvious, but in many respects MD was superior to cassette tape. No tape to snag and ruin your recordings, especially if they were commercial recordings, no editing functions unlike MD which has quite sophisticated editing features, and recordings which are not prone to drop outs, hiss, and other issues with analogue cassette tape decks such as wow and flutter which plagued cheaper decks. A top jolly cassette recorder and properly tuned for a high quality tape, such as my Nakamich 700 Mk.II, fed with a high quality analogue signal could easily outperform even the best MD. But the fact is, that for the majority these technical issues aren’t of any consequence for them. The other aspect though, was cassette was very popular in the Indian sub-continent with literally tens of millions wedded to the format, and it was much cheaper to mass produce.

SACD was another thing. It does have superior audio quality to CD but required expensive machines to play them and the benefits weren’t always apparent unless equipment upgrades were factored in.

I am perhaps better placed than many as I listen with excellent audio gear and can compare music formats covering reel to reel commercial tapes, vinyl, cassette, MD, and SACD, plus computer digital formats mp3, wma, and commercial DAB broadcasts. So I have many comparisons at my disposal. Perhaps too many!

I definitely remember all of these products and you’re right, most of them were technically superior to other formats that those that were more successful. Often a single feature such as the longer playing time of VHS is what consumers gravitate to, but also, support for content can help fuel one format or technology over another. This wasn’t unique to Sony, as the video game console wars often saw systems sell much better than technically superior competitors. The original Sega Master System had better graphics and a more powerful CPU than the Nintendo Entertainment System, and the original XBox was leaps and bounds more powerful than the PS2 to which it competed against, but on both instances, the NES and the PS2 sold way more by virtue of better software support.

Technology is a fascinating topic, and one that if I had more time, I wouldn’t devote just to cameras as I’d love to explore vintage computers, telephones, audio systems, etc!

I had the Canon Ixus (Elph in the US) which as I was working from Canon at the time I got a a significantly reduced price. It was a decent enough camera for family vacations and whatnot. Eventually it died and I never replaced it… I might still have it somewhere…

An interesting anecdote to that original Elph (as I’m sure you’re aware) that the design and lineage of that original camera lived on with Canon’s Digital Elphs. So even though the film format version didn’t last very long, people could still have that form factor for many years to come!

And is it not where we get the term APS for digital crop sensors?

Thanks Mike, Very comprehensive review, I now know more about the APS system than I ever wanted to. I was aware of it back in the date but paid scant heed to it thinking here we go again, having been in the trade during the 126 & 110 days. Being a die hard Canon fan I have 7 of their ELPH/IXUS models and a EOSIX in my collection but have never used any of them and I guess I never will unless I get inspired and find some expired film on ebay. Stop! wait no Labs oh well I have plenty of other cameras I have never put a roll through. – Keep up the great work.

I agree with you that the rise of digital imaging in the early 2000s doomed the APS film system. But I think APS could have done better if the developers had sized it similar to the popular 35mm format. APS film was 24mm wide. A format of 23 or 22 by 36mm would have been close to the popular 24×36mm. Buyers of the new cameras could use their existing lenses without worrying about a conversion factor. The benefits of the new improved film (such as finer grain) soon became available in regular 35mm film, so many photographers said “Why bother?”