This is a Super Kodak Six-20, a medium format folding camera made by Eastman Kodak in Rochester, NY in 1938. The Super Kodak Six-20 is historically significant for a variety of reasons, most importantly, it was the first mass produced camera with automatic exposure. The camera was created by famed designer Joseph Mihayli, and using a coupled selenium exposure meter, the Super Kodak Six-20’s electric eye would automatically choose an aperture appropriate for one of the shutter’s four fastest speeds, a remarkable feat for the era in which the camera was made. In addition, with a coupled split field rangefinder and a fast 4-element f/3.5 Kodak Anastigmat Special lens, the Super Kodak Six-20 was capable of incredible results.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (eight 2 ¼ inch x 3 ¼ inch exposures per roll)

Lens: 100mm f/3.5 Kodak Anastigmat Special uncoated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Split Field Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Behind the Lens Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/200 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ Shutter Priority AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 1173 grams

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/00066/00066.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Super Kodak Six-20 is one of the most historically significant cameras ever made. Featuring an early version of Shutter Priority Automatic Exposure from more than two decades before the feature would be widely supported, the camera was straight out of the future. It had a list of features and an imaginative design thought up by one of Kodak’s most influential designers ever. For as pioneering as the Super Kodak Six-20 was, it was awkward to use, unreliable, and had an extremely high price tag. As a result, very few were made, and fewer are available today, making these one of the rarest and most sought after cameras in the world. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for extreme historical significance as the first commercially available auto exposure camera | ||||||

| Final Score | 15.0 | ||||||

History

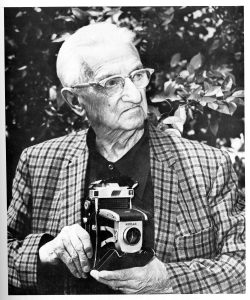

To tell the history of the Super Kodak Six-20, you need to tell the story of the man who designed it. For about three decades from the 1930s until his retirement in 1954, Joseph Mihayli was one of the more innovative and prolific designers in the United States.

Born on January 27, 1889 to Joseph and Maria Mihayli in Apatin, Hungary. As a child, Joe helped in his father’s blacksmith shop. He developed an interest in the design of tools and machinery at a young age and as a teenager completed an apprenticeship as a tool maker and precision instrument maker in Vienna under his father’s direction.

In the summer of 1907, at the age of 18, Joe Mihayli emigrated to the United States with his older brother Frank, winding up in the St. Louis area. There, both Mihayli brothers got jobs at the Wissler Instrument Corp. The younger Mihayli got to work on tool design, his most notable project being a new type of transit used for surveying and other measuring systems.

After little more than a year at Wissler, Joe Mihayli responded to an ad looking for precision instrument makers for the Bausch & Lomb company in Rochester, New York. Seeing this as a more interesting opportunity, in early 1909, Joe relocated to Rochester and worked for Bausch & Lomb. There, Joe used his knowledge of transits and measuring devices to work on similar projects for his new employer. By 1914, Joe Mihayli was involved in the design of military use rangefinders that Bausch & Lomb had signed a contract with the US military for. It was this exposure to mechanical and optical rangefinders that would be Mihayli’s first step towards designing cameras.

In 1917, Joe would leave Bausch & Lomb and take a job at the Rochester based Crown Optical Company. At Crown, Joe was given more creative control over his designs and continued developing his own designs including a massive 23 foot rangefinder for the US Navy. In 1919, he relocated to Washington D.C. while still employed by Crown, to work on additional naval projects for the Navy. At this time, Joe Mihayli became recognized by the Secretary of the Navy as a civilian expert in the field of rangefinder and optical design.

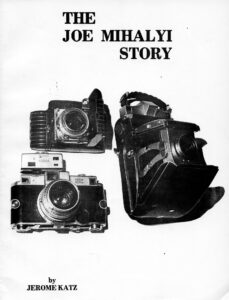

Joe Mihayli continued his work in Washington for the US Navy until 1923 when his former colleague Bill Roach recruited him to Eastman Kodak, back in Rochester, New York. Accepting a new position at Kodak, Mihayli’s superiors recognized his considerable talent and experience and gave him the freedom to work on whatever projects he liked. In a series of interviews between 1975 and 1977 with author Jerome Katz, Joe Mihayli described his early time at Kodak as an independent, free to tackle projects and overcome obstacles that others couldn’t, or didn’t have the time to.

By 1932, Joe had a small department of his own with a small staff comprised of designers, model builders, and instrument makers. He was free to choose his own direction and did not have to seek approval from upper management for each project he was involved with. It was around this time that Joe started to develop some of his most innovative designs. Miyahli credits his motivation to the German Leica and Contax rangefinders which were renowned as the best in the world. Joe was put off that no American company had anything to compete with the superiority of these German cameras.

A year later, Joe began work on a new precision made American camera that was more portable and could take larger photographs with higher resolution than the Leica or Contax. The new camera would eventually become the Kodak Bantam Special, using new 828 roll film.

The use of a roll type film that only offered 8 images per roll was appealing to Mihayli as he thought most photographers would appreciate a camera that makes larger images, but also could be completed faster, not having to wait for up to 36 exposures to complete. Because the film was simpler than the double perforated 35mm film used by the Leica, Contax, and eventual Kodak Retina, it would cost considerably less as well.

Mihayli worked on the Bantam Special with another Kodak designer named Charles Case. Using his experience with rangefinders, a split field rangefinder was used, rather than the coincident image rangefinders used by Zeiss-Ikon in the Contax as he thought they offered better contrast and were easier to see in poor light. The cosmetics of the new camera were designed by famed American industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague, who worked on a number of projects for Eastman Kodak, along with many other American companies.

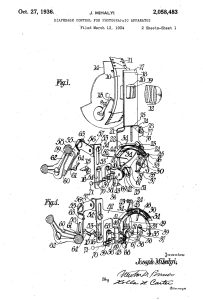

Although heavily involved in the design of the new camera, Joe Mihayli often had multiple projects going on at once, and during the development of the Bantam Special started work on what would become his most significant invention, the world’s first automatic diaphragm. Although other inventors such as Albert Einstein also envisioned the idea of an automatic diaphragm in a photographic apparatus, it was Mihayli’s US patent number 2,058,483 filed on March 13, 1934 that would lead to the world’s first camera with automatic exposure.

After completing a primitive prototype involving a 3 blade aperture connected to a galvanometer and light sensitive cells, Kodak gave Mihayli the green light to design a camera around his new invention. Mihayli foresaw the potential applications of an automatic diaphragm in a photographic camera and began work on multiple designs. Although his earlier 3 blade aperture was the simplest, an aperture priority version that automatically controlled the slit opening of a focal plane shutter was also devised. By 1936, early work on what would become the Kodak Ektra had already started, and according to Jerome Katz’s biography on Joe Mihayli, an application for that camera was in the works, but later scrapped.

To implement Mihayli’s new auto exposure system, an all new camera was designed around it. To keep costs from spiraling out of control, the new camera was to be a folding bellows camera, and retain the simple 3 blade shutter. Not willing to skimp on features, the camera would use one of Miyahli’s split field optical viewfinders. The version included had a triangular rangefinder patch instead of a more common rectangular design like on other cameras. Mihayli’s justification for a triangle patch was that it was easier to calibrate.

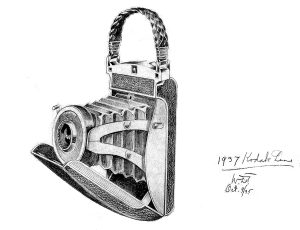

A drawing by Walter Dorwin Teague from the George Eastman Museum dated October 1935 shows a prototype version of Mihayli’s camera. A one piece bottom shell, optical rangefinder, and large selenium exposure meter strongly hint at the Super Kodak Six-20 and suggest design work for it started at least three years before it’s release.

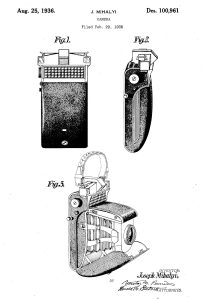

A finalized design of Mihayli’s new camera was submitted to the US Patent office on February 29, 1936 showing a camera remarkably similar to the finished version.

Jerome Katz’s book does not give any hint as to what happened between the submission of the patent design in February 1936 and the camera’s actual debut two years later. This didn’t mean Mihayli sat idle however as much of the work into what would become the Kodak Ektra 35mm rangefinder and Kodak Medalist 2 ¼ inch x 3 ¼ inch roll film camera was well on it’s way.

In addition to these new camera designs, Mihayli worked on a number of patents for more advanced aperture and shutter priority auto exposure systems, a unique automatic focus system that used color fringes to detect distance, new types of film, film cassettes, new shutters, and a huge number of other things, many of which would eventually be incorporated into future designs.

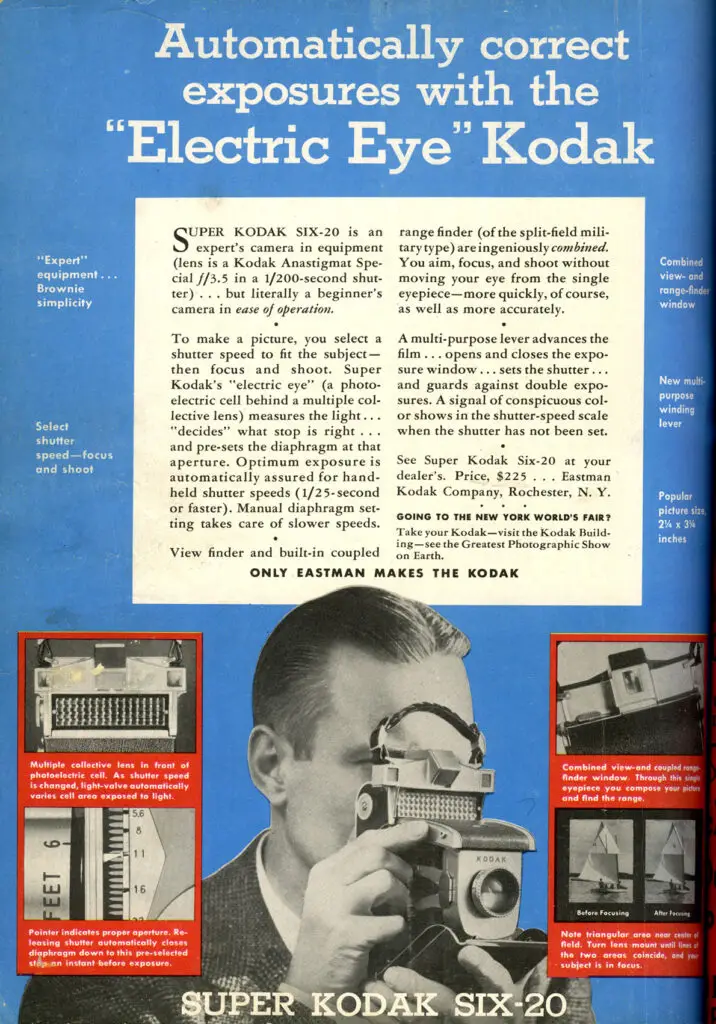

The Super Kodak Six-20 would go on sale in July 1938 for $225 billing itself as “The Camera with the Electric Eye”. In a letter by Eastman Kodak dated January 20, 1960 to someone named John Faber, the writer of the letter confirms the camera’s on sale date, price, and that it was the first still picture camera with a built in photo electric cell coupled to the diaphragm. Kodak did not use the term “auto exposure” to describe the camera as we do today, suggesting that term was not in popular use yet.

When it went on sale, the Super Kodak Six-20 was a technological marvel that likely wowed customers, but with a price of $225, which when adjusted for inflation compares to over $4700 today, the camera was not affordable by many. Further putting the camera at odds with the photographic buying public, most photographers looked at the electric eye feature with skepticism. Cameras had been in use for over half a century without any level of exposure automation, so why now? In the decades that would follow this camera’s release, we saw similar doubts with the release of other new technologies such as more advanced AE and auto focus systems. Photographers didn’t think they needed such automation.

Another challenge for the camera was that unlike many other examples where Kodak “reached for the stars” with cameras like the Medalist or Ektra, each of those were rugged cameras with the US military in mind. The Super Kodak Six-20 had no military application and was far too fragile to be used in any type of severe duty.

Although the camera was only produced for a short time, unsold inventory continued to be offered through at least 1940, possibly longer. An undated ad to the left shows the Super Kodak Six-20 for sale with a price of $202.50, which likely reflects a price reduction in the years after it first went on sale.

There is no doubt, Joseph Mihayli was a dreamer who had a knack for thinking of answers to questions no one was asking, and turning those dreams into reality. Cameras like the Kodak Medalist and Ektra were not bound by sales demands to the masses. Most cameras he worked on were low volume designs that the average person could never afford.

Unlike the Ektra and Medalist which had military use applications, the Super Kodak Six-20 was a consumer facing model. It lacked the toughness or dependability that a severe use camera required. Furthermore, the camera’s strange shape, unfamiliar ergonomics, fragile folding mechanism, and limited top 1/200 shutter speed required a very specific buyer.

Of the cameras that were sold, many were returned to the factory for repairs or adjustment. The camera was simply too advanced for it’s own good and required almost constant maintenance to keep it running. In the letter above from Kodak’s Patent Department, the author of the letter jokes about a familiar expression in which Kodak shipped 500 units in the first year, and repaired 600. It later clarifies that the total number built was 786.

The letter above suggests the camera was sold through April 1945 at which time it was discontinued. While I probably shouldn’t doubt a letter directly from Kodak and from someone who likely had first hand knowledge of the era in which the camera was sold, it’s limited appeal and extremely low production numbers suggest it ended production much sooner. Perhaps the official word of it’s discontinuation didn’t come until 1945, or perhaps unsold inventory was still available at that time, but the camera’s complete absence from all period catalogs and advertisement strongly suggest it was not in active production for very long.

Compared to the Bantam Special, Ektra, and Medalists that Mihayli had a hand in designing, the Super Kodak Six-20 was the lowest seller by a large margin, yet, in his 1977 book about Joe Mihayli, Mihayli himself told the author, Jerome Katz that he considered the Super Kodak Six-20 to be his most proudest invention. In a life that produced over 200 patents and spanned almost half a century of innovation in military, professional, and consumer camera and optical work, this is quite a bold statement.

In 1946 Joseph Mihayli would take a position as the Superintendent of Special Development for Eastman Kodak, a position he would keep until his retirement in 1954. During this time, Mihayli is not credited for any specific camera produced by Kodak, but his influence was felt in a huge number of innovative cameras the company produced during that time and beyond.

Models like Kodak Automatic and Motormatic 35 series had features like auto exposure and motorized film transports, the Kodak Signets 35 and 40 had triangular rangefinders much like the Super Six-20, even later models like the Kodak Instamatic 800 series and X-90 had clever solutions for film advance using a rip cord for tensioning the shutter, a feature clearly influenced by Mihayli’s motorized transport solution for the Ektar and several other cameras.

It is possible Mihayli did work on other models, as in a booklet from 1939 which I’ve previously written about called Major Developments in New Apparatus shows several designs with features very similar to those known to be credited to Mihayli. Prototypes like a 35mm version of the Medalist and a medium format Ektra certainly embody the designs and features Mihayli would have put into them.

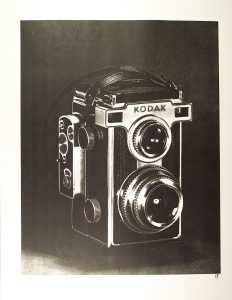

The most amazing Kodak prototype I’ve ever seen was the Twin Lens Reflex design to the left which has a rangefinder that looks very much like that from the Super Six-20. This strange looking TLR had a long list of innovative features such as an interchangeable lens mount, support for automatic exposure, “automat” film advance, and the company’s best lenses. To think that Kodak had someone crazy enough other than Joe Mihayli to think of something like this is hard to believe. I can’t prove this camera has anything to do with him, but I bet it does!

Today, the Super Kodak Six-20 needs no introduction. Even as I first started collecting and writing reviews for this site, I was aware of this camera’s existence and claim as the first ever auto exposure camera. With only 786 ever made, it’s not a camera that you’ll see often, let alone get a chance to use.

As I write this, there are actually three for sale on eBay, ranging in price from $1475 to $2842, all accepting offers. What these cameras will eventually sell for is anyone’s guess. While they are undoubtedly valuable, with so few examples sold, determining a fair market value is very difficult. Needless to say, if you absolutely HAVE to have one, they are out there. Just be prepared to open your wallet!

My Thoughts

In a couple of previous reviews, I’ve made the comment that I do not have an endless supply of cameras to review. Sometimes people will ask me, “why don’t you review this camera or that”, and my response is that I can only review a camera I have access to. Yet, as my list of reviewed models grows and includes rare and historically significant cameras like the Super Kodak Six-20, I’m starting to realize that perhaps my reach for models is larger than I realize.

I had never so much as seen a Super Kodak Six-20 before having the opportunity to review this example. As has been the case for the past couple of years, some of my coolest loaners have come from my friend and fellow collector, Kurt Ingham. Interestingly, Kurt purchased this camera from another collector I know, who wishes to remain anonymous. Needless to say, for those of you who trawl eBay for rare cameras to buy, you’ve almost certainly come across this seller before (no, it’s not Paul).

The Super Kodak Six-20 is a wonderfully strange looking camera, that in addition to it’s historical significance, looks like no other camera made. Using a folding clamshell design, the camera perpetually looks half opened, even when it’s not. Having only seen photos of it online, I was always curious to feel how the opening and closing procedure felt.

When it arrived, the camera was stored in it’s original leather carrying case along with some filters, and a really cool letter from Kodak sent to one of it’s original owners summarizing a repair they had done on it.

The camera is both larger and heavier than I would have expected. The exposure meter, viewfinder, and rangefinder are all stacked in their own module on top of the main body. The outer shell, including both clamshell doors are made of steel covered in some type of genuine leather and accented with chrome bits all over the camera. Kodak often used Moroccan leather in the 1920s and 30s on their premium cameras, but I am unsure if that is what this is. Whatever it is, the leather on this example is in excellent condition, showing no signs of peeling or cracking, and retains it’s soft, supple feel.

The first challenge I encountered after the camera arrived was in how to open it. Although I have handled a great deal of folding cameras and clamshell cameras before, none were like the Super Kodak Six-20. Finding the door release button on the side of the camera below the film loading knob was easy enough, but pressing the button only seemed to pop open the lower clamshell by a small amount. Clearly, this wasn’t a self-erecting camera.

Afraid of damaging one of the rarest and most valuable cameras I’ve ever handled, I pulled down on the lower clamshell until I felt a great amount of resistance and stopped. I could see the top clamshell start to come up and the bellows start to open but it wouldn’t open all the way. Afraid of using too much force, I settled on helping it open by lifting up on the top clamshell while simultaneously pulling out the shutter and lens mount until it was fully erect. It was only after handling the camera for a while that I read the manual and realized that this is the rare case where brute force is necessary. I found that after pressing the door release and the bottom clam shell popping open, that by giving it a firm, but swift tug, I could get the entire camera to pop open erect without damaging anything. I guess this is just how it is!

The Super Kodak Six-20 has a natural portrait orientation, much like most folding cameras of the day. Holding the camera this way is pretty comfortable, however it’s weight combined with it’s strange shape make it awkward to carry for long shooting sessions. This camera still has a weaved leather hand strap on top, but if I were someone that wanted to shoot this camera regularly, I would definitely recommend replacing this strap with something more sturdy, like a neck strap. You can shoot landscape oriented photos on it, but it is very awkward, with the viewfinder now on the side and the shutter release in a rather precarious location.

Looking down upon the top of the viewfinder, the only things you’ll see are the door release latch near the back edge of the left side, and above the top door, is a window showing both the selected shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/200 plus Bulb, and a red shutter readiness flag.

When this flag is visible, the shutter is not set. Advancing the film will also set the shutter and move this flag out of the way. Shutter speeds from 1/25 and up are printed in white, with speeds 1 through 1/10 in red. The four white speeds are the only in which the auto exposure system will work. With a red speed from 1/10 and under, auto exposure is disabled. Although the camera lacks a T or Timed shutter mode, a locking shutter release cable can be used with the shutter set to Bulb.

Flip the camera upside down and the bottom of the camera has the 3/8″ tripod socket, which in this example is filled with a chrome plug that must be removed before you can mount the camera to a tripod, and a small chrome kickstand which when pulled out, allows you to rest the camera on a flat surface. There is no tripod socket on either side of the camera to allow for landscape shots on a tripod, but the camera’s manual suggests that something called an Optipod or Tilt-a-pod can be used.

Around back you can see the rather large opening for the coupled coincident image rangefinder and viewfinder window. The size of the window is truly remarkable, as most rangefinder cameras of this era had very small viewfinder openings. Near the bottom left corner of the door is a red window for reading exposure numbers on the film’s backing paper. Behind this window, inside of the film compartment is a metal door that cleverly swings down, blocking the window from excess light coming in, when the film is not being advanced.

To advance the film, a chrome winding lever on the right side of the camera is used. This lever is normally in a locked position and requires you to lift up on a small handle on the lever’s tip in order to swing it out. Once you pull up on the winding lever, the metal door blocking the red window will automatically swing out of the way allowing you to see the exposure numbers. Advancing the film one full exposure requires multiple motions of the advance lever until the next number shows. Once you’ve made it to the next exposure, push the lever back to it’s original position and lift up on the small handle to lock it into position and close the metal door again. An interlock exists preventing you from firing the shutter unless the winding lever is fully seated into it’s locked position.

The camera’s right side shows several things. First, you can see the tip of the film winding lever that I previously mentioned. Above and to the right of the lever is a chrome knob which is used only when loading in a new roll of film to secure the paper leader to the take up spool. Once a new roll of film is loaded into the camera and the film door is closed, this knob is no longer used. Beneath this knob is a small chrome door release button for opening the front of the camera. Below this, near the leading edge is one of two strut release buttons, the other of which is on the exact opposite side of the camera, and are both used to close the camera. Squeezing these two buttons together allows you to fold the camera shut for storage.

The long rectangular metal slider on the side of the top door is the shutter release. With the shutter set, sliding this lever toward the rear of the camera fires the shutter. In front of the shutter release is a threaded shutter cable socket.

On the left of the camera we see the other strut release button which must be squeezed with the same knob on the other side to close the camera. On the side of the top door is a knurled wheel which changes shutter speeds visible from the top of the camera. This wheel turns smoothly between most speeds, but additional resistance is encountered when moving between Bulb and 1 second, between 1/25 and 1/50, and once again between 1/100 and 1/250.

Warning: There is a large amount of resistance when changing the shutter speed to 1/200. This can only be done when the shutter is not set. Attempting to select 1/200 with the shutter set will not only shred the skin on your fingers, but can also damage the camera, so don’t try it!

Behind the shutter speed wheel is a rectangular slider for the self-timer. The self-timer can only be set after the shutter is set. Trying to do it before won’t hurt anything, but it just won’t work. With the self-timer set, pressing the shutter release will begin an approximate 12 second delay before the shutter is released. The manual doesn’t mention, nor does it appear there is a way to cancel the self-timer once it is set.

Warning 2: The manual also warns that the self-timer cannot be used with the shutter set to either Bulb or 1/200, suggesting that damage to the shutter can occur.

On this side of the metal shutter plate is the aperture and exposure control. A white needle behind a small glass window with f/stops f/3.5 to f/22 indicates the selected f/stop determined by the selenium exposure meter. The metering system on the Super Kodak Six-20 uses a trap needle system that was used by many other companies in the 20th century, in which the meter is continuously measuring light causing the needle to move.

Pressing the shutter release does three things. The first, is that a metal feeler presses down on the needle, “trapping” it in whatever position the amount of light detected, then a second feeler which is directly coupled to the lens diaphragm feels the position of the trapped needle and stops down the lens only until the point where the needle will allow. The diaphragm always starts small at f/22 and opens to whatever point the needle is trapped and uses that for the last step, which is when the shutter is actually fired. Upon releasing pressure on the shutter release button, the two feelers lift up, opening the diaphragm all the way, and allowing the needle to move again.

If you’d like to see how a trap needle exposure system works, check out this excellent video showing how it works on an Olympus Pen EES-2. Although the two cameras are very different, how it works on the Olympus is very typical of the design and almost certainly what’s going on inside the Kodak.

Below this meter window is a metal slider that is used for manual control of the diaphragm. Contrary to some information online which say the Super Kodak Six-20 is completely dependent on the meter, this is not true. In the event the meter is dead, or you just don’t agree with it’s settings, you can use this lever to manually select an f/stop from f/22 to f/3.5. In fact, the Kodak’s user manual states that this is how you control the exposure at speeds slower than 1/25. Moving this slider upward from it’s bottom position raises a metal bar inside the meter window with a black line on it. Position the slider so that the black line points to whatever indicated f/stop you wish, and that is what will be used when the next exposure is made. To use the camera in auto exposure mode, this slider must be all the way down in it’s locked position.

When this camera was new, the idea that a camera could not only detect the amount of light in a given scene, but also adjust the exposure to compensate would have been revolutionary. Although limited in application, the method in which the Super Kodak Six-20 was able to accomplish this was very clever. This “trap needle” system would be the most common method for automatic exposure cameras for the next 20-25 years. It wouldn’t be until the early 1960s when more advanced metering systems would use something different.

A flaw in Kodak’s implementation of the metering system in the Super Kodak Six-20, is that they made no effort to compensate for various film speeds. There is no ASA or DIN speed dial to set on the camera to tell it what kind of film you have in the camera. The camera’s user manual states that the camera is calibrated only for Kodak Panatomic-X and Verichrome films which then would have had a speed of 25 and 50, respectively. It goes on to say that when using a faster film like Kodak Super-XX Panchromatic film which had a speed of 100, that you needed to manually compensate your exposure by changing shutter speeds.

Although you cannot calibrate the meter for faster films, there are ways to account for slower films or when using lens filters. The large selenium meter on the front of the camera has two posts on either side of it which could be used with one of seven masks created for the camera in special lighting conditions. Two masks are designed specially for using the camera with artificial light, and five more masks when using filters over the lens.

A neat feature of the meter, is that behind the clear plastic lens is a set of blinds that are used to block light from entering the actual selenium cell. These blinds are coupled to the shutter speed wheel, so when setting the shutter speed to 1/25, the blinds are completely open, but as you select faster speeds, the blinds start to close, blocking some of the light, calibrating it for the faster shutter speeds. Another feature of these blinds is that when closing the camera, the blinds close all the way, completely blocking light from entering the cell when not in use. This helps protect the cell from wearing out while not in use. I attempt to show how these blades work in a video later in this article.

Up front, the taking lens rotates for focus. You can see the focus distances engraved from just under 4 feet to infinity in the ring around the lens from the side. The focus ring rotates almost completely 360 degrees from minimum to infinity focus meaning that getting precise focus from within the rangefinder is easy, however it does slow you down as it’s nearly impossible to rotate the lens in a single motion.

The viewfinder is surprisingly large and bright, especially for a rangefinder camera from the 1930s. Compared to early Kodak Retinas or the German made Kodak Regent whose viewfinder and rangefinder windows are extremely tiny, the one on the Super Six-20 is quite big and easy to see all four edges, even while wearing prescription glasses. The rangefinder patch is in the shape of a triangle, similar to the one used in the Kodak Signet 35.

Unlike most coincident image rangefinders that rely on a semi-transparent beamsplitter to both split light entering the rangefinder with the main viewfinder, the one in the Super Six-20 uses a prism that does not allow you see both images on top of one another. How the rangefinder works, is the light passing through the triangle rangefinder patch is shifted to the side. By focusing the lens, the light passing through the rangefinder will move, and once it is completely lined up with light in the main part of the viewfinder, then your image is properly in focus. It works exactly the same way as a more traditional beamsplitter rangefinder, but does take a little bit of getting used to as you have to pay attention to the light near the edges of the triangle. Looking directly in the center of the triangle won’t help you get your focus correct.

In a recent review for the Welta Superfekta, which was another strange looking 1930s camera, I found myself struggling to explain all of the camera’s operations so I made a video showing how that camera works. I received positive feedback for the video from readers telling me that the video was helpful in getting some points across that I struggled to do with words, so I decided to do the same thing with the Super Kodak Six-20. The following video shows the entire operation of the camera, from opening it, loading film, and using the camera.

I probably don’t need to tell you that the Super Kodak Six-20 is a cool camera. Not only is it cool, but it is historically significant, innovative, fun to use, and still manages to make great pictures. Sure it’s also awkward to hold, isn’t well suited for images in landscape orientation, and definitely requires you to read the manual (or this review) before you use it, but considering we’re talking about an auto exposure camera from 1938, I think a bit of leeway is deserved.

I would have been absolutely happy if all I ever had a chance to do was hold this camera as having to opportunity to see one in person is not something that every collector can claim. But I was even luckier in that I could actually use it. So if you want to see some images from a camera in which only 786 were ever made, keep reading…

My Results

For owners of the Super Kodak Six-20 back when it was new, in order to make good use of the camera’s automatic exposure, you needed to stick with one of two films recommended for it, which both have slow speeds. As is the case with most of these cameras today, the meter is no longer operational, but thankfully you can still shoot it manually so for that, I was free to use whatever I wanted. Since I had recently gotten a large batch of fresh Foma 100, I chose that for what might be the first roll shot in a Super Kodak Six-20 by anyone in the world, in a very long time!

Seeing the first images from this particular example in what is likely a very long time, I was enchanted by the image quality. Sadly, some issues that I failed to detect before shooting it came to light. The most obvious are pin hole light leaks that are in every image. Even those that don’t appear to show light leaks, they’re there, they just blend into the background. The second issue was some haze that shows up the most images where the sky is present.

Disappointed at the flaws in the images, but also amazed that they looked as good as they did, I knew I needed to shoot one more roll. Normally, I don’t like to use more than a single roll on cameras with issues like this, but the rarity of this camera meant that I didn’t want to send it back without trying again. For the second roll, I used some expired Fuji NPS 160 color. I had shot other rolls from this same batch before and I knew it was good at ASA 100 with some muted colors, but otherwise would still give an idea of what this camera could do with color.

The expired Fuji performed as well as I had hoped, but unfortunately I noticed that with this, the second roll through the camera, the light leaks were getting worse. As I handled the camera and continued to open and close it, the over eighty year old bellows were continuing to degrade, opening up more pinholes. It is clear that if anyone wanted to continue to shoot with this camera, replacement bellows would be a must.

Kodak was no stranger to making good lenses. On models like the Kodak Monitor Six-20 and Kodak 35, their Anastigmat Specials produce images on par with the best German lenses of the day. Sharpness in the center is excellent with only slight softness and vigneting in the corners. Compared to other 2 ¼ inch x 3 ¼ inch or 6 cm x 9 cm cameras of the era, the images from the Super Kodak Six-20 compare favorably.

The Super Kodak Six-20 isn’t a rugged camera as it’s folding struts and clamshell body are subject to damage from bumps and bruises, and like any folding camera, touching the fragile bellows material can cause light leaks to protrude into the film compartment. The camera clearly is no Kodak Medalist, but I also wouldn’t call it cheaply built either. It is clear that Mihayli cared very much about quality, and didn’t want to invest the time and energy in creating the world’s first automatic exposure “electric eye” camera and put it in a cheap body.

Many of the Super Kodak’s features are well thought out and work well. The film advance lever is a nice touch that adds a bit of a modern feel to what would have otherwise been a simple knob wind. That there isn’t a mechanical exposure counter isn’t a big deal as it would have further added complexity and cost to the camera, but the automatic cover for the red window that opens and closes when advancing the film is a nice touch. The viewfinder with it’s triangular split field rangefinder patch works REALLY well and gives you the feel of a high class camera every time you look through it.

The camera’s controls, although not obvious when first looking at the camera, end up being in comfortably located positions while shooting. I found the location of the shutter release to look strange, but to work quite well when handled in portrait orientation. Also, I appreciated being able to change shutter speeds with the wheel on the side of the top part of the clamshell. Again, you’d definitely need to RTFM to know how to use it, but once you figure it out, it’s location actually makes quite a bit of sense.

Sadly, the list of cons is quite long too. Despite ergonomics which I would describe as “better than they look” they’re still not great. While I applaud Kodak and Joseph Mihayli’s futuristic approach, the camera is awkward to hold. Erecting the front of the camera requires an uncomfortably high amount of force. With the camera open, I would be terrified to carry it with me all day shooting images. I would want to keep folding it back shut and reopening it each time I wanted to make a new exposure so as not to damage the folding mechanism or the bellows.

Although the viewfinder works very well in portrait orientation, it becomes very awkward to use for landscape shots, which for me, is my preferred way of shooting a camera that makes rectangular images. It feels very weird to hold this large and heavy object to the side of my face as I look through the viewfinder on the camera’s far edge. I found it was a little more comfortable when shooting landscapes to have the viewfinder turned to the left, so that the shutter release was facing up, rather than the other way around.

Another major flaw in what turned out to be a pretty good first attempt at an auto exposure camera, was that the meter had a default calibration only for films with a speed of ASA 25 or 50. In order to shoot slower films or use filters on the camera, a complex system of filters and masks needed to be used. For faster films, you needed to factor an extra stop using the shutter speed dial. Considering that auto exposure was such a new concept, all these complex “if this then that” adjustments would have likely put off anyone curious about the new technology.

In the camera’s original manual, Kodak only recommends two films for use in the camera, but no mention is made for color film at all. I might have been a little more understanding if this camera was a technology preview by a company who only made cameras, but for this to be made by Eastman Kodak, the world’s largest producer of photographic film seems like an enormous oversight. They should have seen the need for more flexible metering and the need to compensate.

Perhaps I’m being too harsh on such a pioneering camera however, as the technology to do some of the things that we take for granted today (or even in the mid 20th century) simply weren’t there in 1938 when this camera came out.

Nevertheless, the Super Kodak Six-20 sold slowly, most likely due to the 1-2 punch of being incredibly expensive for the time, and featuring a technology that few were asking for, and even fewer still understood. As a result, with such a small number produced, these cameras are extremely rare today. Many collectors consider this camera to be a golden goose or a bucket list camera as finding one, regardless of condition, is not likely to happen often.

Although this camera wasn’t perfect, that it worked enough for me to shoot it at all is amazing, and I consider myself to be extremely fortunate to have the opportunity to put two rolls of film through it. I know most reading this won’t have that chance, and for you, hopefully the text in this review, plus the accompanying video, will help you live vicariously through me!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Super_Six-20

http://www.bnphoto.org/bnphoto/KodakSuper620.htm

https://www.dancuny.com/camera-collecting-blog/2020/5/25/kodak-super-six-20

http://www.phsc.ca/Show_Tell_2001/Text_Files/Bill_Kantymir.html

https://www.flickr.com/photos/kodakcollector/albums/72157649680819394

Thank you for a valuable review, Mike – a keeper along with those Kodak prototypes you told us about a couple years ago. As a regular user of 120 folders, I really like that red window shutter linked to the film advance. In a world of ISO 400 +, tht would be a great feature to have.

Thanks, Mike. Your articles always add a new dimension to my understanding of any camera you review!

Always happy to share what I find! And I appreciate you sending me these wonderful cameras! 🙂