This is an Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic, a 35mm half frame camera produced by Ricoh in 1964 for Ansco of Binghamton, New York. The Memo II Automatic is a name variant of the Ricoh Auto Half which had been in production since 1963, and is also an updated version of the original Ansco Memo Automatic from 1963, adding an accessory shoe to the top plate and including Ansco’s parent company, GAF in it’s name. The Memo II Automatic features shutter priority automatic exposure via a large selenium exposure meter on the front face of the camera. The AE system can be turned off for flash or manual exposures, although the shutter speed remains a fixed 1/30 speed. The camera also has a spring wound film advance in which film is tensioned by a large knob on the camera’s bottom, and after firing the shutter, the motor automatically advances the film to the next exposure and cocks the shutter. Despite it’s small size, the Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic is a capable and well built camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), Half Frame

Lens: 25mm f/2.8 Memar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity with Click Stops for Close-Ups, Near, and Far

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with Projected Frame Lines and Focus Distance Indicator

Shutter: Rotary

Speeds: 1/30 for Flash/Manual Exposure, 1/125 for Automatic Exposure

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ Shutter Priority AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Spring Wound Automatic Film Advance, Wrist Strap

Weight: 318 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/agfa_ansco/ansco_memo_ii.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic is a nicely designed and compact half frame camera built by Ricoh for the American company Ansco. This version of the camera supports full programmed AE and limited manual control. When found in working condition is a capable camera that is very easy to use. The images it makes compare favorably to other good Japanese half frame cameras by Olympus, Canon, and Fuji. The Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic has a distinct look and came in a large number of variations, making it a very good camera to shoot, as well as collect. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.4 | ||||||

History

The Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic and it’s predecessor the Ansco Memo Automatic were both made in Japan, but sold by an American company whose parent company was based out of Germany, making them quite possibly one of the most international cameras ever produced! The story is a bit confusing, but I’ll do my best to summarize it for you.

In the 1960s, the company whose name makes up the first 5 letters of the camera’s name, Ansco, was a subsidiary of a German company called General Aniline & Film Co., or GAF for short. The history of this company is quite long and complicated, and a really excellent timeline compiled by William L. Camp can be viewed here. Here is an abbreviated version.

In 1842, a Columbia University graduate named Edward Anthony opened a daguerreotype gallery in New York city called E. Anthony & Co. Anthony sold daguerreotype chemicals and supplies, but eventually started to manufacture his own cases and other accessories. In 1852, he was joined by his brother Henry T. Anthony and the company was named E. & H. T. Anthony & Company.

Over the course of the next few decades, the Anthony brothers did very well, growing their business to a point in which they claimed to be the largest photographic chemical and apparatus manufacturer in the world. They had a large retail distribution business and made all sorts of camera equipment and photo developing chemicals using all the latest processes. In 1883, the company built the world’s first mass produced instantaneous camera, called the Schmidt Patent Detective Camera.

In 1902, E. & H. T. Anthony & Company would merge with the Scovill Manufacturing Company out of Waterbury, Connecticut who had been in business since 1802. The merged company became the Anthony & Scovil Company, or Ansco for short and they moved their headquarters to Binghamton, NY. The newly merged company was now the second largest photographic film and camera maker in the United States, right behind the Eastman Kodak Company.

Throughout the first few decades of the 20th century, Ansco remained a film first company, but in 1924, would release their first camera, the Automatic Ansco . Four years later, in 1928, the company was bought by the German company AGFA (some sources say they merged, but it’s not 100% clear who was the controlling interest).

In 1939, the parent company of AGFA-Ansco was renamed to General Aniline & Film Company, or GAF for short. GAF was a large multi-national organization whose products extended into the chemical business, one of which was the parent company of Bayer aspirin. GAF would have it’s hand in a large number of other industries as well. Later that same year, AGFA-Ansco officially became a subsidiary of GAF.

Over the course of the next few decades, the two companies operated under the name AGFA-Ansco and would begin a partnership of releasing nearly identical cameras under both names. Some of the cameras sold in the United States were copies of existing AGFA models, but actually made in the USA, and some were directly imported from Germany.

Very few of Ansco’s cameras were designed or manufactured in the United States by the American branch of Ansco . It would seem that Ansco continued to operate as a film first company, and would primarily sell models made by other companies, with their name affixed to them. One notable exception to this was the Ansco Automatic Reflex 3.5 TLR from 1947 which was built in response to an inability to get quality twin lens reflex cameras out of Germany after the war.

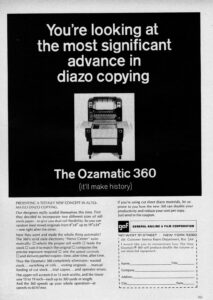

In the late 1950s, one of GAF’s other businesses was making photo copiers, and they had pioneered a new method of copying documents using something called a “Dry Diazo Process”. Prior to the dry process, the method for making photocopies involved wet ink which was slower, took time to dry, and was prone to smears. While I won’t pretend to know much about how these early photocopiers worked, my guess is the dry method is similar to modern “toner” in which a dry powder is used to make a duplicate of an original.

It was around this time that Riken Kōgaku Kōgyō K. K. (later known as Ricoh), had been investing in photocopier technology and was interested in GAF’s dry process. Ansco was looking to expand it’s camera offerings beyond entry level German cameras, so a deal was made. Riken would receive GAF’s technology to produce photocopiers using their dry process, and in exchange, Riken would produce cameras specifically for the American market that would be sold as Ansco cameras. The first camera part of this deal was a rebadge of the Japan only Ricoh 999, called the Anscomark M.

Manufactured in Japan by Riken, the Anscomark M was designed by famed American industrial designer Raymond Loewy. Loewy was responsible for the designs of a huge number of products from the 1920s through the 70s. He came up with designs for Boeing airplanes, automobiles and trucks made by Studebaker and American Harvester, locomotives, appliances, electric razors, and even designs of the famous Coca-Cola bottles and cans. His influence on corporate and consumer products in the middle of the 20th century was significant, so it was likely considered a great honor to have him design a Japanese camera specifically targeting the American market.

The Anscomark M turned out to be a very attractive camera with a compelling feature set, but sold poorly. It’s awkward ergonomics, combined with the fact that by the early 1960s, less and less people were buying interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras, meant that it was largely ignored. The camera was produced for only a short period of time before being discontinued.

In 1963, the Ansco / GAF / Riken relationship would produce another camera, this time something a little more palatable to American audiences. Based off a Ricoh model sold in Japan called the Ricoh Auto Half, the Ansco Memo Automatic was a half frame fully automatic camera with auto exposure, a wind up clockwork film advance, and a fixed focus 4-element Memar lens. The camera was identical in function to the Ricoh version, but was sold in the United States.

The original Memo Automatic was only sold for a very short time, before it was redesigned and upgraded only a year later. In 1964, the Ansco / GAF Memo Automatic II made it’s debut with new cosmetics, the inclusion of Ansco’s parent company, GAF in it’s name, a three zone focusing lens, and an accessory shoe on the top plate.

An ad from the June 1964 issue of Modern Photography to the right suggests the retail price with a soft case and wrist strap was under $70, which likely means $69.50. When adjusted for inflation, this price compares to around $675 today, making it a not-inexpensive, but also not out of reach camera for the photographer wanting a modern Japanese camera with the economy of half frame, but the convenience of automatic exposure.

The Ansco / GAF Memo Automatic II would prove to be popular as the camera was in production through at least 1967, but I could not find an official end date. I also could not find any record of how many were made, but searching for this model on eBay and Google turn up many results, many more than for the original Ansco Memo Automatic which appears to have been made only for a very short amount of time.

Overseas, Japan sold this model under a variety of different names and with some additional features such as a self timer, and also with different color combinations.

A version of the camera called the Ricoh Auto Half SL came with a fast 35mm f/1.7 lens, and versions supporting an accessory electronic flash were also created.

In Europe, another version made for the German photo retailer Photo-Quelle called the Revue Auto Half also exists.

The appeal of half frame cameras was very strong in Japan and the rest of the world in the 1960s, but by the end of the decade would disappear everywhere except Japan. While more half frame cameras would continue to be produced until the 1980s, resistance from American photo finishers plus the increased availability of smaller and more compact full frame 35mm compact cameras ended the demand for half frame 35mm cameras in the United States.

Today, there is a niche market of collectors who enjoy half frame 35mm cameras. As film photography gains popularity and prices rise, the original appeal of twice as many exposures per roll of film is still just as valid today as it was in the 1960s. In addition, half frame cameras often eschewed the generic look of full fame cameras from the same era. With a smaller body came more opportunities for designers to try something new and most half frame cameras have a style that you don’t always see in larger cameras. And of course, the smaller size of the camera makes them easier to carry around so there is still a lot to like about cameras like the Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic.

If you find one of these, whether it’s the plain looking one I have, one of the colored ones available in Japan, or one with the faster lens, these are fun and interesting cameras. They are easy to use and make pretty good images, but the best part is they usually sell for very little, so pick one up if you can!

My Thoughts

Back in 2018 when I reviewed the Riken built, Anscomark M, I told the story of how Riken and Ansco’s parent company GAF reached and agreement to trade GAF’s photocopier technology to Riken in exchange for some cameras to be build for release in the United States. The Anscomark M was the first result of that arrangement, but not the last. The Ricoh Auto Half from 1963 may not have had the distinct Loewy design or interchangeable lenses, but was an interesting camera nonetheless, and when I saw that there was an Ansco name variant, I had to pick it up.

As photos of the camera suggest, the Memo II is a compact camera. It’s square body maximizes the smaller size of the 18mm x 24mm film gate, wasting almost no space. That Riken was able to fit in a selenium meter with the electronics needed for AE, plus a clockwork motorized film transport is impressive. At a weight of only 318 grams, the camera is extremely portable, and hangs comfortably from it’s wrist strap without causing the user much fatigue.

Despite it’s small size and light weight, the camera does not feel cheap. Most of the body is metal, with the only plastic bits being the frame around the selenium cell, the lens cap, and part of the take up spool. Combining a compact size with lots of metal gives a feeling of quality and precision that a more plastic camera might not have. This is clearly not a cheap camera.

Up top there’s not a lot to see. On the right is the accessory shoe which is unique to the Memo II as the original model did not have one. In the center is the name of the camera engraved into the metal, and on the left is a round multifunction dial which sets the film speed, shutter speed, and also functions as a flash guide distance reminder.

Around the perimeter of the multifunction dial is a metal ring which controls the shutter speed and also puts the camera into AE mode. A small window displays f/stops from f/2.8 to f/22 plus an orange “A” for Auto mode. With the camera in any of the manual exposure modes, the shutter speed is set to a fixed 1/30 speed. This is primarily designed for flash photography, but there is no requirement to use a flash. Using slower ASA 25 or 50 film speeds and adjusting for a single shutter speed, it is still within the camera’s ability to shoot those films manually. In AE mode, the shutter speed jumps up to 1/125, and the meter controls the diaphragm. There are no other shutter speed options than 1/30 and 1/125.

In the center of the dial is a second control for film speed. This is needed to use the camera in AE mode but can also serve as a reminder dial for manual exposure. Film speeds from ASA 12 to 200 are supported, somewhat limiting your exposure options.

Finally, near the top of the dial are the letters F, N, and C which correspond to the focus distances of Far, Near, and Closeups which are needed for flash photography. With the camera in manual exposure, you should limit your distance to one of the three settings depending on which f/stop you’ve selected. Using a flash guide number of 100, you are limited to f/4 with the lens set to Far, f/8 with the lens at Near, and f/16 shooting Closeups.

Around back, there’s little to see other than the rectangular eyepiece for the opening. To the left of the eyepiece is a small metal plate reminding you that the camera you are about to put to your eye is, in fact, an Ansco camera.

Flip the camera over and the bottom is where you’ll see the film rewind knob, automatic resetting exposure counter and the large knob for winding up the clockwork film transport. In the center of the motor wind knob is a release button which both acts as a rewind release knob, but also releases tension on the clockwork mechanism so that you may rewind your film at the end of a roll, without having to work against the motor. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made up to the maximum of 72.

The left side of the camera has a PC flash sync port needed to use the camera in flash mode, and a metal 1/4 tripod socket. That the socket is on the side isn’t much of a deal considering the compact size of the camera. With a tripod mounted, the camera would be oriented to shoot landscapes, but if you wanted to shoot in portrait orientation, you’d need a swiveling or 90 degree head. On the opposite side of the camera is a sliding switch which functions both as a shutter lock and door release. Moving the slider in the direction of the Lock arrow, prevents the shutter release from accidentally firing while the camera is in storage, and sliding it in the direction of the Open arrow, releases the film door for changing film. Beneath the slider is a single anchor point for the wrist strap, which thankfully, this example still has attached.

After unlocking the film door, the left hinged door swings open to reveal a cramped film compartment. Film transports from right to left onto a fixed take up spool. Like most wind up motor driven cameras, the take up spool hides some of the internal parts needed to make it work, so it’s diameter is a little thicker than on most cameras. A chrome bracket with a single tab is used to secure the film leader to the spool.

The film gate is 18mm x 24mm and is very narrow, meaning that film has a very short distance to get from the cassette to the gate to the take up spool. This means that in addition to getting twice as many exposures due to the half frame size, you can usually get a few extra images on both the leader and tail of film. A 36 exposure cassette will likely get you arounds 75-76 exposures if you are good about loading film.

The inside of the door has a metal film pressure plate with divots on it to reduce friction as film passes over it. A small metal plate on the door to the left of the pressure plate helps hold the film cassette still as it is in the camera. Unlike many Ricoh cameras of it’s era, the Ansco / GAF Memo II has cloth light seals around the door, which don’t degrade like foam seals on other cameras of the same era. On my example, the light seals still did a good job of protecting the camera, although it is something you should check on yours if you ever want to shoot one of these. Closing the door requires an extra amount of force to make sure the door is securely latched, so that is something to be aware of after loading film.

Up front, the camera would normally come with a large gray plastic lens cap that also covers both the selenium meter and viewfinder. I have to imagine that this lens cap has been lost on a great number of cameras, but if yours has it, you’ll find that by also covering the viewfinder window, it acts as a reminder not to shoot the camera with the lens cap on.

The shutter release is on the front of the camera and is in the shape of a large chrome trapezoid. There is no provision for a cable release, which likely wasn’t a big deal as the camera lacks both a Bulb setting or any speeds slower than 1/30. A chrome ring around the lens allows you to change focus with prominent click stops at letters F, N, and C which stand for Far, Near, and Closeup. Actual distances are not indicated, but the huge amount of depth of field afforded by the wide angle 25mm lens, means that you really don’t need to be very specific. Using an online depth of field calculator, with a 25mm lens at f/5.6 and the lens focused to 8 feet (Near) everything from 5 to 24 feet will be in focus. Stop it down to f/8 and it expands to 4 feet to 100 feet, essentially making it a focus free camera.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical design with yellow tinted frame lines in three of the four corners. On the right side of the viewfinder is a focus distance indicator showing the letters F, N, and C, which act as a reminder to what distance setting you’ve selected.

In the fourth corner, instead of frame lines is an exposure ready indicator. The camera’s manual calls it a “Gold Dot” but it’s more of an oblong oval. The way it works is that with the camera in AE mode, if there is sufficient light to make an exposure, the oblong oval should be visible. If it disappears, then there is not enough light. This indicator is only useful for under exposure and will never tell you if the image will be overexposed however. In the image to the left of the viewfinder, the “Gold Dot” is difficult to see, but this is a result of how I captured the image using my smartphone. In reality, it is much easier to see.

By far, the Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic’s biggest asset is it’s small size and ease of operation. Although the join venture’s earlier Anscomark M was a significantly more advanced camera with a longer list of features and impressive specifications, it was a camera that no one in the early 1960s was asking for. Too advanced for customers who valued simplicity and too proprietary for the advanced photographer looking to get into a new interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder system.

The Memo II was both advanced and simple at the same time and was more in line with what consumers were spending their money on during the years it was in production. But what is it like to use and what kinds of images does it make? Keep reading…

My Results

Sometimes over the course of accumulating cameras with the intent of reviewing them on this site, things don’t always go as planned. When I picked up the Memo II in the summer of 2018, I had intended on reviewing it right away. The camera was in nice shape and appeared to work fine, but for reasons that I cannot explain (or remember) I never got around to shooting it, and it went on my shelf, where it would sit for a couple of years.

One day while talking to the guys on the Camerosity Podcast, talk of half frame cameras came up and someone mentioned the Ricoh Auto Shot that the Memo II and the earlier Memo were both based off and I thought, “hey, I have one of those”. I reached towards the back of my camera shelf, pulled out the camera, blew some dust off it and thought, I need to give this thing a try.

Seeing that not only was the shutter working, but that the diaphragm appeared to respond to changes in light, I thought that I would shoot half of my first roll in manual mode, and the other half in AE mode to compare. Whenever I try some kind of experiment with an untested camera, I usually try to eliminate other variables, so I went with a predictable film that has a lot of latitude, good ole Kodak TMax 100. Frequent readers of this site know I shoot this film a LOT. It works great using Sunny 16 at any speed from 1/30 to 1/250 and can easily compensate for cameras with questionable reliability.

I kind of had an idea of the quality of images I was about to see as I was pulling my film out of the Paterson tank, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned reviewing cameras is that you never know what to expect. While I had high hopes for the Ricoh built Memar lens, I was uncertain how the selenium meter powered AE system would have held up over the past 60 years.

Looking at the entire strip of film, I was elated to see what looked to be properly exposed rolls both on the half I shot in Auto mode and the other half that I shot in flash mode, manually choosing f/stops to adjust exposure.

To my surprise, while scanning the images I could not tell the difference between the AE and manual exposed images suggesting this camera has held up very well. The lens was sharp with some noticeable softness and vignetting near the corners that give it a distinct vintage look. Looking back at my previous reviews of half frame cameras, the Memar appears to be a tick lower in quality than the 5-element Fujinon and Canon lenses on the Fujica Drive and Canon Dial 35-2 respectively, but comparable to the 4-element D.Zuiko on the Olympus Pen EE-S.

Shooting the camera is a mix of old and new. It’s unusual shape and ergonomics and mechanical sounds of the clockwork film advance remind you that this is an antique camera from more than half a century ago, but it’s compact size, light weight, and almost entirely fully automatic operation has the feel of a modern point and shoot camera. There’s no need to adjust for exposure with the camera in Auto, and film advance is automatic as well. Although the camera does not automatically focus, the wide depth of field when shooting Near and Far away mean that you rarely have to be concerned with distance. As long as you aren’t trying close-ups, the camera is very similar in operation to a focus free camera, further adding to it’s automatic feel.

I appreciate that the camera offers the ability to still use it without needing the meter. This will likely be very useful for those who have examples of this camera where the meter has not survived this long. I was lucky to have one that still worked, but as is the case with many other metered cameras, the selenium cells will not last forever and there are many cameras which are completely inoperable with a dead meter. Although the Memo II does not support full manual control, with a single shutter speed and manual control over the diaphragm, you still have some options, if you so choose.

I’ve always felt half frame 35mm cameras were a different breed from their full frame cameras. The 1960s brought additional features to these cameras like wind up clockwork motor drives and auto exposure which added to the appeal of a very compact and easy to use camera. That these cameras were able to produce nice and sharp images that stood up to 4×6, 5×7, and even 8×10 enlargements was impressive, especially considering those were the same sizes that full frame 35mm cameras were producing.

I quite liked my time with the Ansco Memo II as I liked the experience and the images I got from it. Sadly, this camera will likely spend a lot of time sitting on a shelf for one specific reason which is that this segment is full of so many similar excellent, fun and easy to use cameras that produce images with terrific image quality. Nearly every Japanese camera maker made a great half frame camera in the 1960s, so when I want to scratch my 18x24mm itch, I’m probably more likely to reach for the Olympus Pen F SLR, the dual format Konica Auto-Reflex, or the even cooler Canon Dial 35-2.

If you are new to half frame cameras and don’t have access to quite the number I do, or if you just really like having as many half frame cameras as possible, the Ansco / GAF Memo II Automatic is a nice camera that is absolutely worth being added to your collection. Even if you have no intent of shooting it, it’s square shape and dominant meter lens looks great on a shelf. If you are a completist, the Ricoh versions sold in Japan came in a bunch of different colors, so there are a bunch of similar variants to this one to search for. Regardless of your motivation, this is a camera worth considering.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/GAF_Ansco_Memo_II

https://vintagecameralab.com/ansco-memo-ii-automatic/

https://www.135compact.com/135_half_ansco_memo_II.htm

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/155018-ansco-memo-ii-automatic-half-frame/