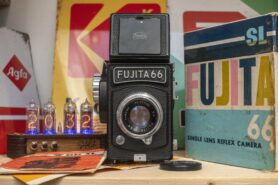

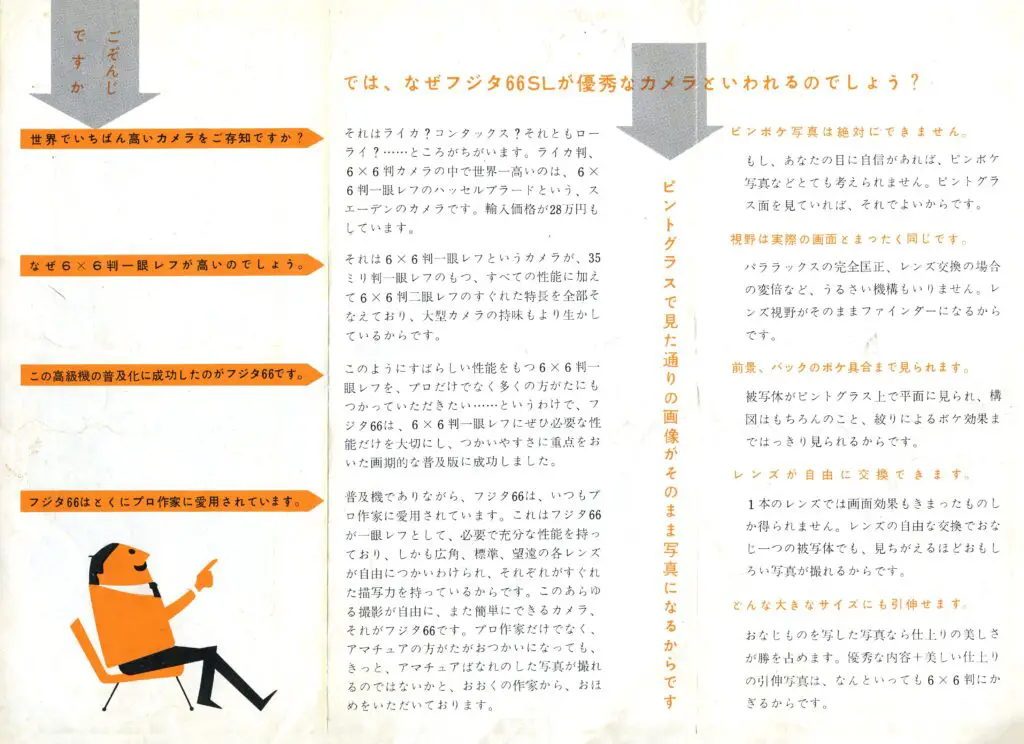

This is a Fujita 66SL, a medium format interchangeable lens Single Lens Reflex camera made by the Fujita Optical Company in Tokyo, Japan between the years 1958 and 1960. The Fujita 66SL is an evolution of the original Fujita 66 from 1956 with the biggest change being the addition of slow shutter speeds. The Fujita 66 series shoots 6cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film and was considered an economic alternative to much more expensive 6×6 SLRs like the Hasselblad and Bronica SLRs. Resembling a TLR with the top half removed, the Fujita offer true through the lens composition allowing for easy focusing and framing, a cloth focal plane shutter, flash synchronization, and an automatic exposure counter. This same camera can also be found rebadged under a variety of brands, such as Kalimar, Soligor, Haco, and Fodor.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 80mm f/3.5 Fujita coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: M44 Screw Mount (Unique to Fujita)

Focus: 1.1 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Reflex Viewfinder and Sports Finder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/5 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold with and PC Socket FP and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Quick Return Mirror, Exposure Counter

Weight: 1086 grams, 912 grams (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/Fujita66SLManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Fujita 66SL is an interesting medium format SLR with a focal plane shutter, interchangeable lens mount, a large viewfinder, and a quick return mirror. Despite having half as many lenses as a TLR, the camera isn’t a whole lot smaller. These cameras have a poor reputation for reliability and are often found today with non-working shutters, but when working are decent shooters, capable of great images. For the entry level photographer in the late 1950s who liked the large size of 6×6 images on medium format film, but preferred through the lens composition, the Fujia series was an affordable option. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

For most people familiar with cameras or photography, the name “Fuji” immediately reminds you of the film company who also makes some pretty terrific digital mirrorless cameras and once made even more terrific-er film cameras back in the day. If you’re not into cameras (then why are you here), there are a huge number of other industries in which a company called “Fuji” does business. There is a Fuji Electric, Fuji Bank, Fuji Heavy Industries, a Fuji television network, a logistics company called Fuji Seal International, and probably a dozen others that still exist today or at one time existed.

This article is not about any of them. Fujita and Fuji, despite sounding very similar are not at all the same company. In fact, there are even multiple Fujitas. One of my favorites is Fujita Shouten C, Ltd which was founded by a man named Den Fujita whose many accomplishments includes bringing McDonald’s and other fast food industries to Japan. Wouldn’t it be cool if I could tell you that the same man who is responsible for Ronald McDonald and the Big Mac also made cameras in the 1950s? Well, I can’t because this isn’t about that Fujita either.

As it turns out, at least two companies with similar names once existed, one called Fujita Kōgaku Kikai, and the other Fujita Kōgaku Kōgyō. According to camera-wiki, the relationship between these two companies (if any) is unclear, but also, it is unclear whether or not these names belong to the same company as it was very common for Japanese companies to change their names as they ebbed and flowed through multiple industries. Many early Japanese companies who produced cameras and lenses, did not start out that way. The company that became Konica can trace its roots to a drug store, Fuji (the film company) was once primarily a cellulose company, and Kowa was once a textiles company.

Whatever the case, Fujita the optics company seems to have started during or immediately after World War II, probably as some sort of manufacturer or distributor of photographic goods. At least one site suggests Fujita started out in 1928, but I don’t believe that to be true as the same site credits Japanese Wikipedia which only has a page for Fujita the industrial company who had a significant event in 1928.

Camera-wiki suggests that Fujita Kōgaku Kikai was listed in an 1943 listing of Japanese lens makers, which seems plausible to me as there were a great deal of small companies in Japan making lenses at the time. We also know that at some time between 1953 and 1954, Fujita Kōgaku Kōgyō began work on a prototype medium format 6×6 SLR. The difference in the two names Fujita Kōgaku Kikai and Fujita Kōgaku Kōgyō is “Fujita Optical Machinery” versus “Fujita Optical Industry”. I am going to go on a limb here and suggest that either the two companies are exactly the same, and just changed their name, or the original Fujita Kōgaku Kikai was reorganized into a new entity called Fujita Kōgaku Kōgyō. I think that is going to be the most plausible explanation anyone will be able to find with the resources we have today.

Prototype Mystery: In my research for this review, I came across a single page that claims a prototype version of the Fujita 66 was actually designed by Heinz Kilfitt as early as 1952. Kilfitt is best known for creating the original version of the Berning Robot, and for creating Kilar lenses usually designed for the Alpa SLR, but have been made in a variety of other mounts. In 1953, a 35mm SLR camera designed by Kilfitt and made by a company called Metz Apparatefabrik was released. The Mecaflex exclusively featured Kilfitt’s own Kilar lenses, and remained in production until 1958.

A prototype SLR simply called the Kilfitt 6×6 was shown around the same time the Mecaflex was released suggesting that Kilfitt perhaps wanted to get into both 35mm and medium format SLRs. Although two Kilfitt 6×6 SLRs have been shown, one looks very different from the Fujita, but the one to the right shares some similarities. The design of the viewfinder and location of the various knobs, accessory shoe, and flash sync port on the camera’s left side are all in the exact same locations as would appear on the Fujita. In addition, the camera very clearly has a lens mount with a built in focus helix, just like the Fujita. The one and only image I was able to find for this camera is too low of resolution to see fine details, and we don’t know exactly when this camera was designed, or when it might have gone on sale, but it looks close enough to the first Fujita to where it seems plausible that Kilfitt’s 6×6 SLR eventually became the Fujita.

What relation Heinz Kilfitt might have had with Fujita Kōgaku Kōgyō is unknown, nor is there any info as to why the Kilfitt version was never released. If I had to make a wild guess, perhaps Fujita was tapped to build the camera all along, but negotiations broke down, or perhaps production delays thwarted Kilfitt’s original plan, and rather than abandon the project altogether, perhaps Fujita decided to tweak the mostly finished design and release the camera themselves.

In any case, Fujita Kōgaku Kōgyō produced a prototype in 1953 or 1954 and began mass production a year later in 1955. The new camera was called the Fujita 66 and was primarily made for domestic sale. The ad to the left from a 1956 issue of Asahi Camera and shows a price of ¥24,000 which was comparable to that of the Super Fujica 6 folding rangefinder camera and about double that of a Yashicaflex TLR.

Two versions of the camera were made for export to the United States starting in 1956. One version was called the Kalimar Reflex, and sold by the US distributor Kalimar Inc which imported a large number of Japanese cameras in the 1950s and 1960s. Another was the Soligor 66 which was imported by Allied Impex, the same company that distributed Miranda SLRs. In the ad to the right for the Soligor 66, the price was listed as $99.95 which when adjusted for inflation, compares to a little over $1100 today.

The original version of the Fujita 66 was updated twice, first in 1958 and was called the Fujita 66SL with the primary change being the addition of two slower shutter speeds, 1/5 and 1/10, selectable via a separate slow speed dial. Cosmetically, the only other change was to Fujita logo on the front of the camera which went from a script typeface to one that was less script-like. In addition, the words “Model SL” was engraved into the side of the camera, right above the flash sync speed lever.

The second change came in 1960 and was called the Fujita 66SQ. This camera extended the slow speeds down to 1 second, the quick return mirror was replaced with an instant return mirror, and the kit lens may or may not have been changed to a slightly faster f/2.8 design.

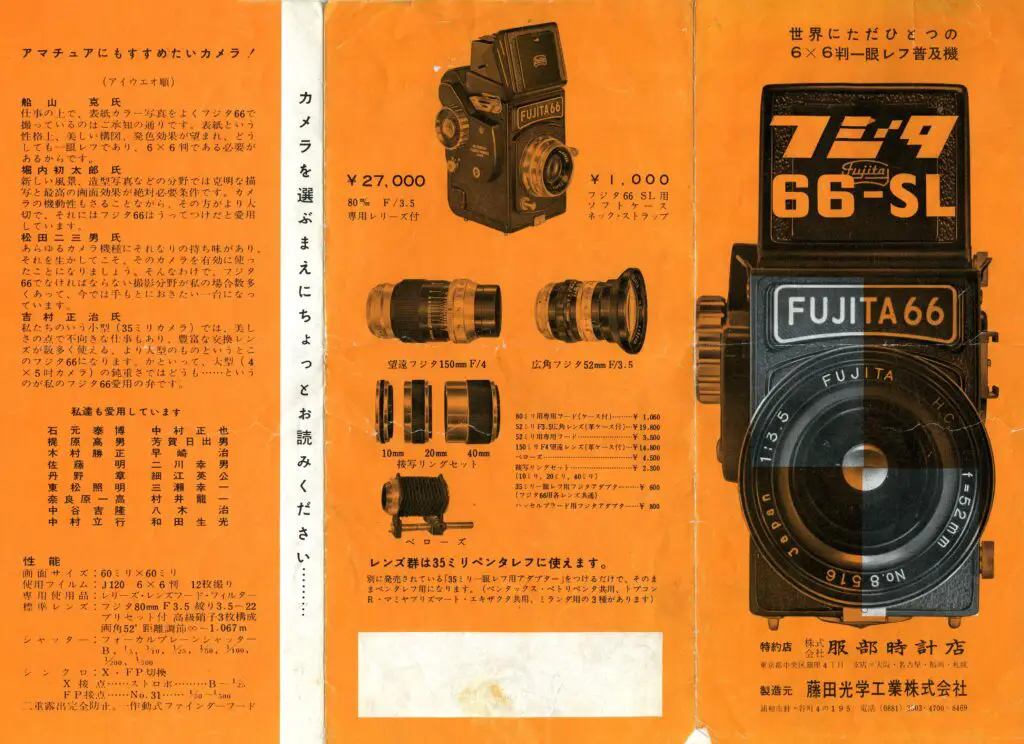

Information is scarce about the Fujita 66 cameras, and what can be found has a lot of misinformation. On the camera-wiki page for the Fujita 66, the article states that only the 80mm kit lens was ever made for the camera, yet examples of two accessory lenses, a 6-element 52mm f/3.5 wide angle lens, and a 5-element 150mm f/4 lens were mentioned in the Fujita 66’s user manual and in a pamphlet shown above. In addition, there was a bellows attachment and three different extension tubes, a 10mm, 20mm, and 40mm for close up photography also available.

In addition, that same camera-wiki article also says the Fujita 66SL lacks an instant return mirror, which is technically true but misleading as the Fujita 66SL does have a quick return mirror. The article suggests that the mirror doesn’t return at all, similar to early SLRs in which the mirror will only drop when cocking the shutter for the next exposure. The difference between an instant return and quick return mirror, is that with an instant return mirror, the mirror action is coupled directly to the shutter and drops down immediately after the shutter closes. With a quick return mirror, the mirror action is coupled to the shutter release button, and goes up and down as you press the shutter release, independent of what the shutter is doing.

I discussed the difference between a quick and instant return mirror in my review for the Asahiflex IIa 35mm SLR which was the first 35mm SLR to have an instant return mirror. All previous Asahiflex SLRs were like the Fujita 66SL in which the mirror was of the quick return type. This minor difference is important to note as the Fujita 66SL has slow shutter speeds down to 1/5 of a second, which means you need to maintain pressure on the shutter release until after the shutter closes, because if you release the button too quick, the mirror will drop down blocking light before the exposure has finished.

A year after the original Fujita 66 was released, the Kalimar and Soligor branded versions were exported to the United States, and would remain in production for longer than Fujita branded models. As best as I can tell, the Fujita branded ones stopped being made around 1959 – 1960, but at least the Kalimar ones were sold through 1963. The final version of the Fujita 66 was sold in the US only as the Kalimar Six-Sixty.

In addition, Fujita branded TLRs called the Fujita AB and Fujita C also exist and were likely produced in the late 1950s. My best guess is that Fujita had distribution deals with these overseas importers, but chose to make a small number for sale in Japan under their own name. The domestic market was very crowded in the late 1950s and it would have likely been difficult to get products into consumers hands, so export deals were probably much more profitable.

After the Kalimar Six Sixty stopped being offered, Fujita seemed to disappear from existence. I found no other reference to the company or its name after that time. More than likely, the company probably went out of business due to extreme competition in the Japanese market and a lack of interest in economically priced medium format SLRs. If there was any part of Fuijta left in the early 1960s, it likely was absorbed by another company.

Today, 6×6 SLRs are highly desirable, as long as they’re made by Hasselblad, Mamiya, or a few select other companies. The Fujita and its American versions are but a curiosity of a forgotten era. That these cameras were cheaply made and suffered from inconsistent quality control has tarnished their reputation over the years. It is difficult to find one today in good working order, so the demand is quite low.

If however, you just like interesting Japanese cameras with unique combinations of features, or like a challenge in a quirky and unreliable camera, a Fujita might be right for you. I wouldn’t pay a lot of money for one, but when found in good condition, should be capable of wonderful images.

My Thoughts

When it comes to medium format SLRs, there’s one of three primary designs. The most popular is the “Hasselblad” style, in which a modular body, usually in the shape of a cube has a removable back, removable lenses, and removable viewfinder. Hasselblad produced cameras like this all the way from the model 1600F from 1948 all the way up to when they stopped making cameras. A few other companies like Bronica and Mamiya and the Soviet Arsenal factory with their lineup of Kiev SLRs followed this same basic approach with much success. Then you have the style of camera popularized by the Kochmann Reflex-Korelle in which a large mirror box is permanently attached to a pretty normal roll film compartment, with the general shape of a 35mm SLR, just bigger. In addition to the Korelle, many other companies copied this design, most prominently, Pentacon with its Praktisix and Pentacon Six models.

Finally, you have the “half TLR” design like the Fujita which originated with the KW Pilot Six from the late 1930s. For reasons I’ll never understand, this design seemed to be the least popular, despite being essentially a single lens version of the TLR which was very successful. Take a regular TLR, move the reflex mirror to the bottom of the camera and give it the ability to swing up and down and then chop off the entire top half of the camera and you have the basic design of this style camera. The closest camera to the Fujita’s design which I’ve used was made by Kowa and that camera didn’t work, so I was super eager to give this camera a try. It had a funky odor, but appeared to be working!

Before I begin, I probably should walk back one of my comments from the previous paragraph where I state that the Fujita is half of a TLR. While yes, it has half the number of lenses, but when placed next to a normal TLR like a Rolleiflex T, the Fujita is only a couple millimeters shorter. Next to the original Rolleiflex from 1929 and the Fujita is actually taller, so the camera isn’t quite as small as I’ve led you to believe, but it does feel smaller.

Fujita might be a name that many people don’t know today, but it has the feel of a high quality camera made by another company with a very similar sounding name. The camera is quite heavy at 1086 grams, heavier than a Yashica D or Minoltaflex TLR. The all metal body lacks any weight saving materials, has tight tolerances, and each of its controls moves with purpose and without any looseness.

Up top, we see the lid for the viewfinder with an etched Fujita logo in it. There is no release for the viewfinder hood, to open it, you simply lift up on it. A strange quirk of the hood is that it does not open as wide as a typical TLR. Although the viewfinder screen shows a life size 6cm x 6cm image, you need to raise the camera a little closer to your eye to see the entire image without having the front or rear of the hood block any part of the image. In use, it is not a big deal, just something you don’t see too often.

The viewfinder benefits from a Fresnel focusing screen and is very bright, especially compared to similar cameras of the era. I found the image to be evenly bright in the center across most of the frame with only the slightest bit of vignetting near the corners. Inside, the viewfinder isn’t quite as bright as medium format TLRs and SLRs from the decades to come, but is still very good.

It is very important to remember that this isn’t a TLR in which the viewfinder lens is always wide open, and sometimes even brighter than the taking lens. The Fujita 66 is an SLR, so you are looking through the taking lens and the diaphragm, so you need to remember to always open it up for maximum brightness. You can still use the viewfinder with the lens stopped down, but that dims the image. There is no automatic diaphragm on this SLR like later 35mm SLRs would have, so if you do open the diaphragm to increase viewfinder brightness, you need to remember to stop it down again to your desired f/stop before firing the shutter. The center of the focus screen has a circle, which doesn’t seem to have a purpose. There is no microprism circle or split image focus aide to further help you focus the image. There are also no grid lines or any type of indicators for shutter speed or exposure information.

On the back edge of the viewfinder hood is a metal button that when slid to the right, releases a hinged magnifying glass for precision focus. The magnifying glass on the Fujita is huge! Much larger than those on pretty much any other TLR I’ve used, and is something I wish other cameras had. Also like a TLR, with the magnifying glass up, a square hole in the back edge of the hood can see through an opening on the lid that when opened works as a sports finder. This is useful when using the Fujita to take fast action shots of things at or near infinity where critical focus is not needed. Simply hold the camera up to your eye, look through both openings and what you see is about what you’ll capture on film.

Flip the camera over and the Fujita has four feet near each corner which match the height of a central 1/4″ tripod socket in the center. This combination of four feet plus the tripod plate allow the camera to sit level on a flat surface. Near the front edge of the tripod socket is the film compartment release. To open the back of the camera, push the release in the direction of the arrow and the door becomes unlocked and ready to open.

Around back, there’s nothing. Literally nothing, not even a red window for viewing exposure numbers on the film backing paper.

Both sides of the camera have strap loops which allow you to attach a neck strap without have to rely on a leather case, which is a feature I always prefer as I am not fond of using potentially stinky and dry rotted ever ready cases, half a century after they were made.

The right side of the camera is quite busy, starting with a large film advance knob and shutter speed dial in the middle. The shutter speed dial works similarly to those found on 35mm cameras with focal plane shutters in which you must lift up on the outer ring and rotate it so that a red dot aligns with one of the available shutter speeds from 1/25 to 1/500 or Bulb. The Fujita supports slow shutter speeds using a separate dial, so 1/25 is printed in red, which indicates both the speed it must be set at to use the slow speeds, and also the flash X-sync speed. With the main shutter speed selector at the 25 position, you can choose two additional slow speeds using a smaller dial beneath the film advance knob, 1/5 and 1/10.

To the right of the slow speed dial is a window for the automatic exposure counter. Every control I’ve mentioned, the film advance knob, both shutter speed selectors, and the exposure counter are on a raised protrusion \which sticks out from the main body of the camera. On the rear edge of this protrusion is a sliding button with the word “SET” and an arrow which functions as the exposure counter reset. Pressing this button in the direction of the arrow resets the counter to the “S” position, which is where it must be to start a new roll of film.

The left side has an accessory shoe with the flash sync port below it, and a switch underneath a raised protrusion with a sync speed lever letting you choose between FP bulbs and electronic X-sync. Above and to the right of the sync switch and below the sync port are two knobs that are connected to pins inside the film compartment. Pulling these out while installing film in the camera allows you to more easily insert the spools without the pins getting in the way.

Inside the film compartment, the Fujita reveals one of its most interesting features, the cloth focal plane shutter. Although some TLRs were made with focal plane shutters, they were not common, so seeing one here is a bit of a surprise. Otherwise, the film compartment looks like a regular TLR. New spools of film are loaded into the chamber at the bottom of the camera and an empty take up spool is moved to the top. As previously mentioned, two knobs on the left side of the camera can be pulled out to make inserting the spools in each of the supply and take up sides easier. A red dot on one of the left film rails indicates the position the “Start” mark on a new roll of film must be at before closing the door. Having this film in this exact position ensures that the first exposure is made at the beginning of the film.

Up front, the lens is the most significant feature, or rather, the lens mount as the Fujita supports interchangeable lenses via a 44mm screw mount. Although the 80mm f/3,5 lens is the only standard lens available, both a 52mm wide angle and 150mm telephoto lens were also made. Later versions of this camera were sold under the Kalimar name as were lenses made for that camera which also work on the Fujita. The standard 80mm lens has a focus ring with a handle which makes changing focus easy and a depth of field scale nearest the body which allows you to easily zone focus the camera. Not well documented online, but the 80mm lens is a preset type, in which you can pre-select an f/stop between f/3.5 and f/22 and using a smaller ring in front of it, you can quickly open and close the diaphragm without having to look at the scale again. This makes using the viewfinder easy as you can preset the lens to something like f/11, then open the diaphragm to maximize brightness, then stop it back down to f/11 without having to remove your eye from the viewfinder.

The lens mount is an ordinary screw mount, turn counterclockwise to remove the lens and clockwise to install it. Below and to the left of the lens mount is the shutter release, which works as you’d expect. The 44mm diameter of the lens mount matches that of Miranda SLRs, but is not compatible as the flange focus distance is way off. If however you want to shoot some extreme closeups, you could use a Miranda lens on the Fujita. If it were me however, I would prefer one of the accessory lenses made for this, or one of the Kalimar branded cameras instead.

Overall, there’s little to not like about the Fujita 66SL. It has what feels to be a very good build quality, most of the advantages of a TLR, but also some of the advantages of an SLR. It has what appears to be a good lens with the option to change to something else, a focal plane shutter with a decent range of speeds, and pretty straightforward operation, what could go wrong?

My Results

I go through a bottle of HC-110 about once every two years, and this past summer was time for my every other year order, so upon adding some of my favorite developer into my cart, I perused what kinds of film was available. Realizing that my supply of black and white 120 film was mostly expired stocks, I decided I should get something fresh. Of course I am a cheapskate, so I didn’t want to get anything too expensive. Good for me because at that time Foma 200 was on sale, so I picked up several rolls. I got a mixture of rolls in their generic packaging and a few of those “retro” ones they sell in the colored FOMA boxes. I know the film isn’t any different, but I liked the look of the boxes and thought they would display nice on my shelf next to some cameras, so I ordered some, and as it would turn out, the Fujita 66SL would be the first camera to use one of those rolls in a September trip to the local cemetery.

I have to imagine that at some point in the mid to late 1950s, the standard for what you should expect from a 6×6 SLR had reached a level to where it wasn’t just about image quality anymore. Things like usability and additional features were likely the things that sales people used to sell one model to a customer over another. I say that because when a camera from a little known company like Fujita can make images that look as good as the ones above, trying to tell images apart from an entry level Japanese SLR compared to a top of the line Hasselblad would be pretty tricky for all but the most discerning photographers.

The images I got from the 80mm Fujita lens were quite stunning. Sharpness is excellent in the center, and tapers off to a slightly soft, but still pleasant amount near the corners. In images where the sky was present, I noticed a slight amount of vignetting, but nothing that would detract from the overall look. In fact, what few imperfections I could see in these images, gave them more character than those you might get from a technically perfect Zeiss Planar on a much more expensive medium format SLR.

The image quality of these shots certainly were worthy of a second roll as I would have liked to see how the deep blue lens coating on the Fujita lens performed with color film, but unfortunately, shutter issues started to present themselves while shooting the camera. I could detect the sound of a shutter “not sounding right” a couple times while using the camera. Immediately upon hearing what sounded like a shutter failure, I would retake the shot, and things would return to normal. After developing this first roll, it was clear the shutter was not separating correctly as I got 3 shots out of 12 in which only the bottom 20% of the image was exposed and the rest was blackness, confirming my suspicions that something was amiss. Considering this camera likely hasn’t seen a service bench in many decades, and never had the best reputation for reliability even when new, I didn’t want to continue to push my luck with another roll. Still, from what I got, I feel comfortable declaring that when properly serviced, the Fujita 66SL is a winner!

Using the camera was unremarkable, but in a good way. I found the ergonomics of the camera to be good. I didn’t care for the location of the shutter speed dial as I had to fiddle with it to change speeds, unlike that of a Hasselblad or Bronica in which the ring is around the shutter, but to be fair, those are significantly more expensive cameras. I liked the location of the shutter release and focus arm. Using them both while looking through the viewfinder was intuitive.

I was not a fan of the viewfinder, but it had nothing to do with brightness as I found it to be bright enough that I had no issues seeing focus in moderate light, however dark interiors were still a challenge. The issue for me was the way in which the hood was designed. Compared to a normal TLR in which the sides of the viewfinder hood stand up nearly perpendicular from the ground glass, on the Fujita, both the front and back parts of the hood are tapered in somewhat, giving the actual opening into the viewfinder a slightly rectangle shape.

To be clear, the viewfinder is square, it is the opening to the hood that isn’t. This meant that if I held the waist level viewfinder at waist level, I could not see the top and bottom edges of the focus screen. In order to see the full square image, I had to raise the camera almost to chin level to see past the hood. I found this to be a strange design choice of whoever made this camera as I’ve never seen another camera like it. In fact, the first time I opened the hood on this camera, I didn’t think it was open all the way, as if something was obstructing it, but that appears to be normal. In any case, it is not a dealbreaker, just a strange and unnecessary oddity.

The lack of an instant return mirror was not at all a problem for me. The only time I would think this could cause a problem is at the slowest shutter speed, which I did not test. Pressing the shutter release to raise and lower the mirror seems like an acceptable compromise for what was essentially an entry level medium format SLR.

Beyond the viewfinder, a slightly unfavorable location of the shutter speed dial, and the lack of a feature that wouldn’t have made a significant improvement into the usability of the camera, there is a lot to like about the Fujita 66SL, especially when you consider its price. The Fujita/Soligor/Kalimar branded 6×6 cameras were produced for over 5 years for good reason, they were simple, easy to use, produced good images, and were affordable. Sadly, their reliability has come into question in the years since their release, so finding one in good operating condition is going to be a challenge, but when found working, this is a fun, and very capable camera.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Fujita_66

http://rick_oleson.tripod.com/index-36.html

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/247836-fujita-66-medium-format-slr/

https://web.archive.org/web/20100104113718/http://medfmt.8k.com/mf/fujita66.html (archived)

There was also a 240mm F/4 and a 300mm F/5.5 or 5.6 released later on for these cameras, both with PAD type automatic aperture stop down mechanisms. The 52mm F/3.5 lens was notable for being the first retrofocus lens available for MF, released at some point during 1957. It’s not easy to pinpoint the exact release date for the lens, but I’m of the opinion that this lens most likely beat Asahi’s 35mm F4 to the title of first Japanese SLR retrofocus lens, that’s if Fujita’s 35mm F/2.5 lens they released in several mounts, wasn’t even earlier.

Compare this Fujita to the KW Super Pilot 6×6, and you’ll discover that Fujita’s camera is well ahead of the KW item in build quality. The Super Pilot boasts the feel of a square tin can.

I have a KW Super Pilot 6×6 also and while the two cameras share a similar shape and are technically 6×6 SLRs, they are quite different. For one, the KW uses a trap “guillotine” style shutter, similar to the early Ihagee Exas, the Fujita uses a focal plane shutter. The KW is much more crude, and was built 20 years earlier. Interestingly, if you want to see a camera thats almost a copy of the Super Pilot, look at the Chinese Great Wall DF-series from the 1980s. Those are very similar.

Ilford Kentmere is a good, relatively low-cost 120 film stock.

An 44mm adapter to mount the Fujita/Kaligar lenses onto the Hasselblad f1000/1600 bodies was available, as the 3.5/52 was a unique wide angle that was not available in any other system. I have the 3.5/52 and 4/150 with the adapter to work on an old (mostly working) f1000…