This camera is called the Wica, it is a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Wiener Camerawerkstätte (Vienna Camera Workshop) in Vienna, Austria in 1948. The Wica is a loose copy of the Leica II rangefinder as it shares some similar design elements, but is otherwise a very different camera. The Wica is extremely rare with less than 200 thought to have been made. This example is serial number 139 so is an earlier version with a short top plate similar to that of the Leica. It has a coincident image rangefinder window separate from the main viewfinder, a unique ~32mm screw lens mount with body mounted focus helix, a removable back, cloth focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/20 to 1/1000, and some type of 2-post flash synchronization. The film gate is narrower than a typical 35mm camera, shooting images that are about 32mm wide. The Wica is entirely hand crafted, so there are many subtle variances between models with later versions have a completely different top plate, different flash sync, and other cosmetic and functional differences.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), 24mm x 32mm exposures

Lens: 5cm f/2 Rodenstock Heligon uncoated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: 32mm Screw Mount

Focus: 0.4 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder and Viewfinder Window

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: Z (Bulb), 1/20 – 1/1000 seconds (slow speeds indicated on dial, but not selectable)

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Twin Post Flash Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 792 grams / 652 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Wiener Camerawerkstätte Wica is an ambitious Austrian made 35mm rangefinder camera in the style of the Leica II. While it shares many features with other cameras of the era, the way in which the Wica operates is different. The camera is equal parts high quality, but also very crude at the same time, with open holes and rough corners in the viewfinder, but with an accurate and easy to use rangefinder and excellent Rodenstock lens. This is a rare camera not likely to show up for sale often and probably belongs on a shelf, rather than in use, but if you are crazy enough to shoot some film in one, is a pretty good camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for extreme rareness and wow factor | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.7 | ||||||

History

A great deal of time has been invested on this site and elsewhere regarding the earliest days of the photo industry, but a huge portion of what most people know is limited to what was going on in Germany. What is less discussed (at least on the sites I’ve read), is how much of a roll Austria, specifically Vienna, played in those early days.

Going back to the earliest days of photography, the world’s oldest optics company, Voigtländer was founded in Vienna in 1756 by Johann Christoph Voigtländer. Often credited as a German company, Voigtländer was originally from Austria. Almost a hundred years later, Voigtländer teamed up with Jozef Maximilián Petzval to build the original brass Petzval lens, a design that is credited for influencing nearly every photographic lens which came after. Petzal himself studied and taught mathematics at the University of Vienna from 1836 to 1877 which helped to advance the creation of more advance optical lenses for use in telescopes and other military optics in the years and decades to come.

Throughout the rest of the 19th century, a large number of photographers were active in Austrian and Hungarian empire. A large number of cameras were built in or around Vienna such as the Stereo Daguerreotype camera to the right, created by Wenzel Prokesch around 1845. According to the list of cameras at photohistory.at, the Austrian photo industry was quite prolific.

By the 20th century it seems, the photographic capital of the world had shifted to Germany, with a large concentration of camera makers in the Dresden area, likely due to that regions huge manufacturing infrastructure and excellent transportation hubs. Still, many small Austrian companies such as Österreichische Telefon Fabrik AG, Präcita, and R. Lechner churned out a huge number of large and medium format cameras.

In my research for this article, a name that came up a couple of times was Raimund Gerstendörfer who worked for a company in Vienna called Wiener Camerawerkstätte which translates to English as Vienna Camera Works or Factory. The first reference to a camera designed by Gerstendörfer was a prototype 16mm stereo panoramic camera from 1926. The camera used dual Citonar lenses to produce 11mm x 40mm panoramic images on bulk 16mm film.

A second camera designed by Gerstendörfer and credited to Wiener Camerawerkstätte was a twin lens reflex called the Picoflex which shot 3cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film. The Picoflex was created in 1929 and bares a similar appearance to the KW Pilot TLR, which was another 3×4 TLR camera made around that time. The Picoflex appears to have made it past the prototype stage as a few are known to have been sold, but was still produced in very low numbers. The Picoflex to the left was sold in June 2015 at Westlicht for 5400 Euro.

A few other cameras were credited to Raimund Gerstendörfer such as a prototype SLR and spring wind motorized film camera, suggesting that Gerstendörfer was all over the place with his work. He did not seem to have one single type of camera that he preferred to work on. He did everything!

Perhaps as a way to produce something more consumer friendly, in 1948 a new camera called the Wica, seemingly short for WIener CAmera, made its debut at the Vienna Autumn Fair in 1948. It was promoted as the definitive Austrian camera, built to satisfy even the most pampered demands.

The Wica is considered by many to be a competitor or even a copy to the Leica rangefinder which was the most popular 35mm rangefinder camera in the world at the time. Comparisons between the Leica and Wica show a body with a vaguely similar shape and an interchangeable screw mount, and separate viewfinder and coupled rangefinder windows, but upon even the quickest of inspection, the two cameras are more different than they have in common.

For starters, all Wicas were built entirely by hand using available parts and materials, which at the time were still very scarce after the war. As a result, each and every Wica camera is unique, and has small variances in machining and materials compared to others made. The feature set of the Wica was pretty good, with a flash synchronized focal plane shutter, accurate rangefinder, removable film back, and a selection of high quality German, French, and Austrian lenses available.

Two distinct versions of the Wica were produced, the earliest of which are called the short top where a raised portion of the top plate covers only the viewfinder and rangefinder mechanics, but not the rewind knob, and a second model from 1950 called the long top, where the top plate extends to the edge of the camera, encapsulating the rewind knob into a recess. In total about 150 of the short top models were made, with even less of the long top models. According to coelncameras.com, less than 50 of the long tops were made, with total production of all Wicas at 200 or less.

Most Wicas use a 32mm screw mount with some later ones using a 39mm mount similar to the Leica. Whether you have the 32mm or 39mm screw mounts, no lenses are interchangeable with the Leica. In the 32mm mount, at least seven different 5cm or 50mm lenses were made by companies like Angenieux, Berthiot Flor, Rodenstock, Steinheil München, and Carl Zeiss, with options from Steinheil, Zeiss, Schneider-Kreuznach, and Kahles were made. With such a seemingly random selection of lenses made for such a short produced camera, it is very possible these lenses were modified or adapted by the factory or even third parties to fit the camera, as it seems implausible that companies as big as Carl Zeiss and Schneider would create lenses in such small numbers. Two different 10cm telephoto lenses were also produced for the Wiha, both by Kahles, but no wide angles.

Comparing a Wica to an original Leica, in addition to all of the cosmetic differences between the two, another major difference is in the build quality of the camera. The Wica very much resembles a hand built low production camera with inconsistent quality control. Machining marks in the chrome plates, especially around the edges are common, as are sharp edges to the metal inside of the film compartment. The latch used to attach the film back to the body of the camera is very crude, and almost certainly was prone to light leaks.

With so few produced, it is not clear how this camera would have been marketed or sold. Did Wiener Camerawerkstätte intend to mass produce this camera as an Austrian alternative to the Leica, or was it always supposed to be a “by request only” model sold through boutique dealers? If there was a plan to distribute this camera, were there ever any promotional materials made, and if so, how much was the camera going to cost? If the plan all along was to make these one at a time, who was their target customer? By the time these cameras would have went on sale, Ernst Leitz had already started production of real Leicas, and while I don’t pretend to know what kind of commerce existed between Germany and Austria at that time, I have to imagine Leicas weren’t impossible to get in Austria. We’ll likely never know the answers to this question as most, if not all, the people directly involved with this camera are likely all gone by now and there doesn’t appear to be any surviving documentation.

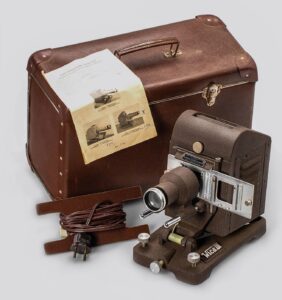

We may never know the intent of Wiener Camerawerkstätte’s desire to build the Wica, but it is pretty clear that a lack of raw materials, difficulty in production, and low interest doomed the Wica, and it appears to have been the last camera produced by either Wiener Camerawerkstätte or Raimund Gerstendörfer. In the early 1950s, Wiener Camerawerkstätte would continue on building a line of slide projectors, flash units, stereo rails, and enlargers. For at least the projectors, the “Wica” brand name was reused on at least one model. The example to the left is thought to have been built in 1952.

What became of the company after that is unknown, but it was clear that Austria’s once thriving photographic and optical industries was a distant memory.

Today, cameras from Austria are sought after by the most dedicated collectors, likely due to a combination of their rarity and obscurity. Quite simply, most beginning to moderate film enthusiasts have likely never heard of the Wica or the company who made it. Furthermore, its often unjustified categorization of “just another Leica copy” fails to do the uniqueness and interesting history of the camera any justice.

With less than 200 made, the Wica is one of the rarest cameras I’ve ever been able to give a full review of. This exact camera went unsold at the 40th Leitz Photographica Auction with an estimated selling price of between 5000 – 6000 Euro. It previously sold at Christie’s in June 1995 for 2138 GBP.

I don’t know how this particular camera went from those auctions to the person I got it from, but I have to believe that at whatever time another one shows up for sale, the prices will be comparatively high and well outside the budget of anyone reading this article, myself included.

My Thoughts

There are Leica copies and there are cameras that people say are Leica copies, but aren’t really. In the case of the Wiener Camerawerkstätte Wica I would definitely agree that the people who made this camera clearly had the Leica in mind when they started, but the finished product has so many differences, I don’t really know that it still qualifies as a “copy”. After all, if the the list of differences is longer than the list of things that are the same, how can you? Regardless of the classification, the Wica exists, is very cool, and absolutely worthy of a deeper look.

From a distance, the Wica definitely has a screw mount Leica look. Many of the camera’s controls are in the same locations as and look similar enough to support the Leica copy label. Upon closer examination, many differences become apparent.

The first, are obvious signs of this cameras hand made, low production build quality. While I wouldn’t go as far as to say it feels cheap, but looking at the quality of the chrome finish, you can clearly see machining marks all over the top and bottom plates, especially near the edges. Near the rewind knob, on the side of the raised portion of the top plate is a metal L bracket which appears to be original, helping to prevent the raised portion of the top plate from separating from the bottom. The metal used to make these plates were likely hand formed, and variances in the smoothness and finish are very apparent.

Inside of the film compartment, the metal body has sharp corners that further hint at a cruder manufacturing process. Peering through both the viewfinder and rangefinder windows, you can see the inner workings of the rangefinder mechanism including screw heads and sp;rings which are not visible in other German, Japanese, or Soviet Leica copies. Finally, the fit and finish is subpar compared to the real thing. My impression of the overall build quality of this camera would be slightly below that of even a Soviet FED or Zorki rangefinder. If this sounds like the start of a pretty poor review, the good news is that it does get better.

Up top is where the Wica most closely resembles a Leica. On the left is the rewind knob. The later “long top” versions of the Wica have a completely different rewind knob that is recessed into the plate. On the raised portion of the top plate are logos for the camera, and “R. Gerstendörfer” who designed in, accessory shoe, and the shutter speed dial. The shutter speed dial is a single piece dial that rotates while advancing and firing the shutter. Like all cameras with rotating shutter speed dials, it is important to not touch it while firing the shutter as it will throw off the timings. Engraved into the shutter speed dial are speeds from 1/1000 to 1/20 plus Z (Bulb). Strangely, the 1/20 position is marked as 20-1 which suggests the camera has slow speeds, but it does not.

To the right of the shutter speed dial and on the lower section of the top plate is the combination film advance knob and exposure counter both of which function exactly the same as on the Leica, and the shutter release button. The shutter release is externally threaded for a cable release. Normally cameras like this would have some type of screw in collar around the shutter release which is not present on this camera. Looking at photos of other Wica cameras I’ve found online, none of the short top versions have a collar around the shutter release, however one long top one does, so I am unsure of how this would have come from the factory. I attempted to screw in one taken from my Leica IIIg and a Leotax rangefinder and despite looking similar, neither would fit correctly. One last thing on this side of the camera is what appears to be some kind of adjustment port above the shutter release. Normally when these type of ports exist on cameras, it is to adjust the rangefinder, but the location of the one on the Wica is not where the rangefinder is, so I am unsure of its purpose.

The base of the camera has on one side a 3/8″ tripod socket in which this example is screwed in a 1/4″ adapter. The adapter does not look original and was likely put in by some previous owner of the camera. Back when the Wica was made, European cameras commonly came with 3/8″ tripod sockets. Regular use of 1/4″ sockets did not happen for another decade or so.

Both sides of the Wica look different from any other Leica or Leica copy due to the nature of the removable back. As I write this, I cannot think of another screw mount 35mm rangefinder camera with an entirely removable (not hinged) back. Chrome edges on both the main body and the back line the sides. Metal tripod lugs are on the extreme edges of the top plate which would be a good way to keep the Wica safe while out shooting with it.

Around back there are two eyepieces for the rangefinder on the left and the viewfinder on the right. The two windows are spaced apart, similarly to the Leica IIa/IIIa. Later versions moved the two windows closer together to minimize the distance your eye needs to move to go between the rangefinder and viewfinder. The only other thing you’ll see on the back of the camera is the sliding lock for the film compartment. The Wica has an entirely removable back and bottom, similar to the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and Nikon rangefinders. Although a simple design, I find the design of this lock to be precarious. Releasing the lock requires a tremendous amount of finger pressure and even after unlocking it, the rear slides along a track which has a great deal of resistance. While age certainly is contributing to the roughness of removing the back, I don’t see any damage to the back or sides on this camera, so I suspect that even when new, removing the back was not a smooth process.

By far, the crudest part of the camera is within the film compartment but I’ll get to that in a minute. The basic layout of the film compartment is pretty standard. Film transports from left to right onto a non-removable metal take up spool. The take up spool has a metal clip on the bottom for holding the leader and works similarly to pretty much any other back loading 35mm camera. Inside of the film door is a normal looking black painted metal pressure plate. There are no additional springs or rollers to help aide in film transport smoothness. The camera’s serial number is stamped into the metal film gate and the inside of the rear door. A possible explanation for why the serial number is stamped into the door is because each was machined to work together, similar to how early Nikon rangefinders were. If a collector were to have two similar Wicas, swapping doors would result in them not fitting together correctly.

As for the build quality, the crudeness I spoke of before is visible almost everywhere. The entire film gate looks like a giant metal box with sharp right angles and corners all over the place. The film gate lacks any type of polished film rail, and is entirely covered in a matte black paint. The paint is oxidizing in multiple areas of this camera, giving it an almost speckled look. Looking above and below the take up spool and the film sprocket shaft, you can see the inner workings of gears, shafts, and other parts normally covered by most cameras. Perhaps the most glaring example is on the side of the film gate, next to where the supply cassette goes, is a large rectangular opening revealing the entire shutter curtain and ribbon assembly from that side of the camera. I cannot recall any other camera which exposes its curtains like that.

Up front is where the Wica has the most changes compared to other screw mount rangefinders. Starting from the left, below the film advance knob are two flash sync ports. I am unsure of exactly what type of flash cord could be used with these ports, but that’s what they are for. This style of flash port is unique to the short top Wica. The long top versions switched to a single flash sync port elsewhere on the front of the camera. Beneath the sync ports is a large knob reminiscent of the slow speed dial on other cameras, but is actually the A/R film transport dial. Although unmarked, when the dial is turned all the way counterclockwise, film transports as normal. When turned all the way clockwise, the film can be rewound back into the cassette.

The Wica has a 32mm screw mount which is the smallest diameter screw mount I’ve seen on any 35mm rangefinder camera. A possible explanation for its smaller size is that the Wica has its own body mounted focusing helix, scale, and focusing arm. Unlike the 39mm Leica Thread Mount where each lens has its own focusing helix, the 5cm Rodenstock Heligon does not have one.

This of course causes the same problem as with the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and Nikon rangefinders in which only the 50mm or 5cm lenses will focus correctly. Since the Wica was designed to have an interchangeable lens mount, it stands to reason that lenses of different focal lengths were planned and if built, would have had to have their own focus helixes. I am unsure of how that would work as I’ve never seen an auxiliary lens in great enough detail, however a possible clue is that the 32mm lens mount is both internally and externally threaded. Perhaps these external threads were for attaching lenses of different focal lengths which likely had their own helixes.

The Wica’s viewfinder and rangefinder windows work as you’d expect. The rangefinder is on the left and has a magnification ratio that looks similar to the 1.5x of a Leica in which everything is larger than it appears. The rangefinder window is tinted yellow with a clear rangefinder patch that takes up almost the entire window, allowing easy operation. Against all odds, I found the one on this camera to be accurate! The viewfinder window is not magnified and represents a full 50mm view of what the lens will capture. Like the rangefinder, the viewfinder window on this camera is clear and very easy to use. Within both the rangefinder and viewfinder windows, some screws and other inner workings of the camera can be seen further continuing the crudeness of this camera.

Holding the Wica is a strange experience. The Wica is a heavy and solid feeling camera with a build quality that seems lower than that of even most Soviet rangefinders. As mentioned probably a dozen times already, it is a crude camera that has the feel and look of a prototype. Despite all of this, everything on this camera works as it should. The shutter fired at all speeds and had no obvious light leaks, creases, or holes. The viewfinder and rangefinder windows were both clear and accurate. I don’t know how many camera of this rarity are still in such excellent operating condition, but whatever that number is, it likely is very low.

What do you do when you have a working camera? You load in some film and take it out shooting, which is exactly what I did!

My Results

For the first time in an unknown amount of time, or perhaps ever, I loaded in a roll of bulk Kodak TMax 100 into the Wica. The shutter seemed to fire at every speed, although I couldn’t be certain of what the actual speeds were due to the shutter speed knob being a bit wobbly, but I figured that with enough latitude, I should get something. In addition to latitude, I have a huge amount of TMax 100, so even if the images don’t turn out, I had a good amount to spare.

Shooting a rare camera with questionable build quality like the Wica was an interesting experience. At times, I felt like I was using a robust and stout German camera, and at other times I felt like the thing was a ticking time bomb, ready to explode at any moment. Sometimes I would wind on the film and it felt like something was binging up and I was about to tear the film out of the cassette and others, it was smooth as any Leica. Choosing shutter speeds was an uncertain experience as the shutter speed selector is very loose and doesn’t drop into position with as much reassurance as I would like. Even though I saw the shutter fire at every speed before I loaded film in it, once you begin a roll, there’s no way to really know if it decided to stop working. Finally, even though the rangefinder did appear to line up correctly at infinity, there was a lot of debris and other obstacles in there that often got in the way causing me to sometimes question whether I was focusing correctly.

When I finally finished the roll and developed it, I held my breath as I removed the lid on my Paterson tank and saw the freshly developed film for the first time. To my surprise, I saw a whole roll of properly exposed and in focus (at least to the naked eye) images. One thing that struck me which I hadn’t noticed before was the frame spacing. Instead of the usual 1-2mm gap seen on film shot in most 35mm cameras, the gap on these was about double that. At first I assumed that the frame spacing was just off, but then I noticed that each image only spanned 7 film perforations instead of 8. Upon further inspection, I learned that the film gate on the Wica was about 32mm wide, instead of the normal 36mm. Cameras that shot 24mm x 32mm images were pretty common in postwar Japan as models like the original Nikon and Minolta rangefinders shot 32mm wide images, but seeing that from a company outside Japan is not common.

Once I got the images scanned into my computer using my “new to me” Epson Perfection V750 Pro scanner, I was quite impressed by the quality of the images. For as unproven of a design that the Wica camera is, the Rodenstock Heligon is a proven performer. A 6-element design similar to a Schneider Xenon or Voigtländer Ultron, this 5cm f/2 lens returned images with excellent sharpness. I didn’t notice any vignetting, but then again with 4mm shorter images than I would normally see on a 35mm camera, its possible things might have gotten cut off.

The Wica did suffer from some random light leaks, and a few spots where you can see the shutter slowing down while moving causing inconsistent exposure, but that is completely understandable for not only a hand built camera, but also a camera that’s approaching 76 years old! I was amazed that I got anything at all!

Amazingly, the shutter speeds were close enough to be within the latitude of the Kodak TMax 100 and in my usual mirror selfie pics where I set the shutter to 1/20 and f/4, exposure was pretty spot on! I took one more interior photo at a storage unit by my house that came out properly exposed as well, suggesting the slow speeds were pretty close to accurate as well.

The rangefinder was accurate as most images were in focus, but I did notice that on over half of the images, my compositions were off to the left, suggesting the viewfinder is not correctly lined up with the lens. Most rangefinders have what’s called a parallax effect in which close focus objects are off the closer and closer you get to minimum focus. I don’t think that is what happened here as I missed it on objects focused far away as well. Looking at the gallery above, you can see my compositions shifted to the left on the images of the mausoleum steps, my feet, the storage lock pic, and the one of the sidewalk, which I had intended to be in the center.

Beyond that, the camera performed well. The lens made nice and sharp images, the shutter was accurate enough between 1/20 and 1/200 (I did not try 500 or 1000), and the rangefinder was accurate at all distances. For as much time as I’ve spent talking about how different the Wica is from a regular Leica, I’ll admit that when shooting it, the experience was very similar. There are a lot of ways in which the two cameras differ, but not the shooting experience. For the most part, I felt as though I could use this camera exactly the same way as any screw mount Leica, or any of the accurate copies made by Canon or other companies. I feel as though had the Wica been a more successful mass produced product, it likely would have drawn good praise from its customer base wanting an “Austrian Leica”.

It probably doesn’t make much sense to come up with a list of cons for a low production hand built camera that wasn’t built for very long, but there is one suggestion I might have given the design team at Wiener Camerawerkstätte had they consulted with me during the design phase of the camera. Overall, I think they did a fine job, however their choice of a unique lens mount with built in focus helix simply doesn’t make sense. It is clear this camera took inspiration from the Leica, but why not just copy the Leica’s mount like pretty much everyone else did? Not only would doing this instantly make more lenses available for their new camera, it also simplifies the design, making it cheaper, and more reliable, but also that it doesn’t require any comporises when mounting a lens with a focal length different than 50mm. Zeiss-Ikon and Nikon got around this limitation by using a lens mount with both an internal and external bayonet, but this unnecessarily complicates things. Just leave the helix in the lens and be done with it.

Maybe it is best that the odd strange lens mount remained as it makes the camera more interesting than “just another run of the mill Leica” copy. At least it makes this review more interesting!

Anyway, the Wiener Camerawerkstätte Wica is a really neat camera that despite many differences from the real thing, actually shoots like a Leica and with the excellent Rodenstock Heligon lens mounted to it, is capable of excellent images, even if they are 4mm narrower.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Wica

https://coelncameras.com/blogs/coeln-cameras-blog/wica-wiener-camerawerkstaetten-35mm-camera

https://corsopolaris.net/supercameras/LeicaCopy/copieleicaIII.html

https://www.jogeier.com/gerstendoerfer-wica-wiener-camera-35mm-rangefinder-leica-2110000351984

Hi Mike,

Another very informative post and the links to the Leica Photographica show many of the unique points you describe.

You mention the fully removable back of the Wica and how you couldn’t think of another 35mm RF camera with a similar set up.

There’s the (slightly quirky) French FOCA PF series that were designed pre-war and appeared from 1947 to the mid 1960s – you reviewed a non-working copy in October 2020 – which also has a removable back too.

At the moment both my copies (a PF3L and a PF2B) are away – one having the low speeds looked at if possible and the older 2B being assessed for new shutter curtains.

And I’ve not taken a shot with either!

And a well-known dealer warned me – after I’d bought both cameras naturally – that FOCA cameras in general were known for their shutters failing, a point supported by the number of non-runners on eBay.

Goodness knows how much the cost will be!

Good call on the Focas, I forgot about them. Amazingly, I have a review of the Foca Universel R coming very soon. I didn’t think of them when I was writing the Wica review as I was only thinking of Leica copies and although the Foca is similar, there’s more differences than similarities, including the lens mount. The screw mount on the PF cameras is smaller than LTM and the Universels have a bayonet. Still, it is a 35mm rangefinder, and has a completely removable back! 🙂

Thanks for your rapid reply Mike.

In truth I think very few people think about any of the FOCA range, given the problems not just with the shutter but also the general finish.

Not only do you have to contend with a unique lens mount on the PFs (as you noted), but if you lose the take-up spool that’s a quick route to a happy weight.

I’ll look forward to reading your review of the Universel R – which was at least a little more conventional… for a French camera!

Thanks again and take care.

My earlier comment had a typo.´A quick route to a happy weight’ should have read ‘A quick route to a happy PAPER weight’.

Dont forget the zorki 3, 3m, 3C, 4, 4, and also the FED 3, 4, 5, 5B and 5C too which had completely removable backs as well

And my lovely ‘new’ Kiev 4 (plus the Contax designs it was based on) and not forgetting the Nikon S too.

Interesting how many FSU camera designs stuck to the removable back when adding a hinge and side latch would have been relatively easy.

But perhaps when you are churning out millions over decades in places like Russia and Ukraine you become conservative (with a very small ‘c’) in your outlook.

When I shot pro with the original Nikon F, I learned how to change film while crouching, with the back resting on my lap or thigh. Got to be second nature after a while.

Thanks for a review of a very rare camera. I am surprised that the crudely-finished film gate did not scratch your film.

Yeah, it’s definitely a risk of scratching film. I bet if I ran enough rolls through, some would eventually come out scratched.

Nice article!

As far as I know, Zeiss never delivered a lense to Gerstendörfer.

The only existing Wica with Tessar (demounted from a Kine-Exakta) is modern fake, as can be seen from the wrong (SLR) FFD (blurred pictures). Originally the identical specimen (“body”) was eqipped with a rare fast Angenieux (without thread mount)!

Normally, the lenses were fixed. There are only a few Short Top WICAs with 32mm thread mount: perhaps all specimens with Rodenstock and some with Angenieux.

https://blende-und-zeit.sirutor-und-compur.de/thread.php?board=3&thread=279&page=2

The Wica was advertised as the Austrian alternative to a Leica II – it even looks like a Leica III! – and was relatively high-prized. The poor workmanship was not only due to the post-war years (especially 1948) but also due to sloppiness. The mechanics is as simple as possible and the quality of the materials is very low.

Nevertheless, the Wica was the gem of Austrian 35mm cameras and has its own charm.

Roland