This is a Chinon Bellami, a compact 35mm point and shoot camera made by Chinon International Corp in Tokyo, Japan starting in 1980. The Chinon Bellami was one of the smallest full frame 35mm cameras ever made and has a design and feature set very comparable to the Olympus XA2 which came out at the exact same time, suggesting the two models competed against each other. The Chinon Bellami has a unique barn door mechanism that protects the lens when not in use which is opened and closed by pressing forward on the film advance lever. The camera has full programmed automatic exposure with no option for manual control. It is a manual focus camera and has manual film advance and rewind. The camera supports flash photography via a detachable Chinon Auto S-120 Flash which was usually sold with the camera when new. When the flash is not needed, it can be removed from the camera, significantly lowering the size of camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35mm f/2.8 Chinonex Color Lens coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 3.5 feet / 1 meter to Infinity with Green Click Stops at 10 feet / 3 meters

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 35mm Albada Type Frame Lines, 0.5x Magnification

Shutter: Seiko Program EE Shutter

Speeds: 1/8 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ Red LED Slow Shutter Speed Warning and Programmed AE

Battery: (2x) 1.5v SR44 Silver Oxide Battery, 1.5v AA Alkaline Battery for Flash

Flash Mount: Removable Chinon Auto S-120 Electronic Flash, Flash fixed to f/4 at all speeds

Other Features: Power Switch and Front Barn Doors Close with Film Advance Lever

Weight: 228 grams, 316 grams w/ Flash

Manual: https://butkus.org/chinon/chinon/belami/chinon_bellami.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Chinon Bellami is an equal part economic point and shoot, yet extremely capable camera. The camera is easy to focus, handles exposure extremely well, and makes excellent looking images with it’s 4-element Chinonex lens. There are a number of cameras that have a similar feature set which the Bellami compares favorably to, and like those other cameras, its small size makes it extremely portable for the perfect “zoo camera” or spontaneous street shooter. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for excellent balance of quality and portability, the ultimate compact point and shoot | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

![]() Chinon was a brand of cameras that for a couple decades in the late 20th century produced a huge number of cameras of all different sizes and styles, some under their own name, but many branded by other people. If the primary types of cameras you like to collect are from the early or middle 20th century, you likely have never heard of Chinon, nor have people who shoot digital photography today.

Chinon was a brand of cameras that for a couple decades in the late 20th century produced a huge number of cameras of all different sizes and styles, some under their own name, but many branded by other people. If the primary types of cameras you like to collect are from the early or middle 20th century, you likely have never heard of Chinon, nor have people who shoot digital photography today.

For those active in the 1970s, you probably remember them as a maker of discount screw mount and Pentax K-mount SLRs. Their cameras were quite well built, but they weren’t exactly a company known for innovation. In fact, many Chinon made cameras were rebadged and sold under the brand names of other manufacturers such as Argus, GAF/AGFA, Revue, Sears, Alpa, and Albinar. As a result, there are far more Chinon made cameras out there than most people probably realize.

The company was originally formed by Chino Hiroshi in September 1948 as Sanshin Seisakusho in Tokyo, Japan. Unlike other Japanese optical companies of the time, Chinon seemed to be in the business of making parts for other optics companies. As best as I can tell, in the 1950s, they made camera lens frames and lens barrels for a variety of companies. It doesn’t look like Chinon had any of their own optical products until 1958 at which time they released their first 8mm motion picture camera lens.

The company would change its name in 1962 to Sanshin Optics Industrial Co. Ltd, and then once again in 1973 to Chinon Industries Inc. As best as I can tell, the company’s first 35mm camera was made in either 1971 or 1972, and I believe it was the Chinon M-1, a rather basic mechanical SLR with an M42 lens mount.

Finding a comprehensive history of Chinon and their early products has proven to be a bit of a challenge. For a brief moment in the mid 1970s, they released a couple of innovative aperture priority auto exposure cameras using the M42 screw mount called the CE Memotron series. The Memotrons used a clever shutter release that would stop down the iris and take an AE reading moments before firing the shutter. Other companies had attempted AE on screw mount cameras, but they usually had a compromise such as requiring a special lens for it to work correctly. The Memotron series would work with any screw mount lens, as long as it had the automatic diaphragm pin.

When looking at Chinon’s product offerings in the 1970s, it was clear the company didn’t strive for the cheapest possible product, but also didn’t aim for the top either. Chinon cameras, whether it was one of many screw mount or Pentax K-mount SLRs, or one of the company’s compact point and shoots, were sold on value. Chinon cameras were good enough for most people, but would never impress a pro or advanced amateur looking for the highest possible quality lenses and state of the art features.

Which is why in 1980 at the Chicago PMA show, the company released a curious little camera called the Bellami. Hot off the heels of the Olympus XA2, which was an incredibly compact 35mm full frame camera with clam shell design, manual focus, and manual film advance, the Bellami answered the question of “how small can you make a full frame 35mm camera, but still give it a good lens, and the ability to make good photos”.

Head to head, the Olympus XA2 and Chinon Bellami had an almost identical feature set, from a similar 4-element in 3-group 35mm lens, support for full programmed AE, manual focus, manual film advance, optional accessory flash module, and a clamshell design that protected the lens and powered down the camera when not in use. Minor differences between the two were a slightly faster f/2.8 lens and top 1/1000 shutter speed in the Bellami, but the XA2 had a still very good f/3.5 lens and top 1/750 shutter speed. The XA2 supported a self-timer whereas the Bellami did not, and relied on a three zone focus system compared to the full focusing lens of the Chinon.

In terms of size and price, both cameras were nearly identical in size and weight, and carried list prices within $10 of each other, although I suspect that street prices for the Olympus might have been a tick higher due to better brand recognition.

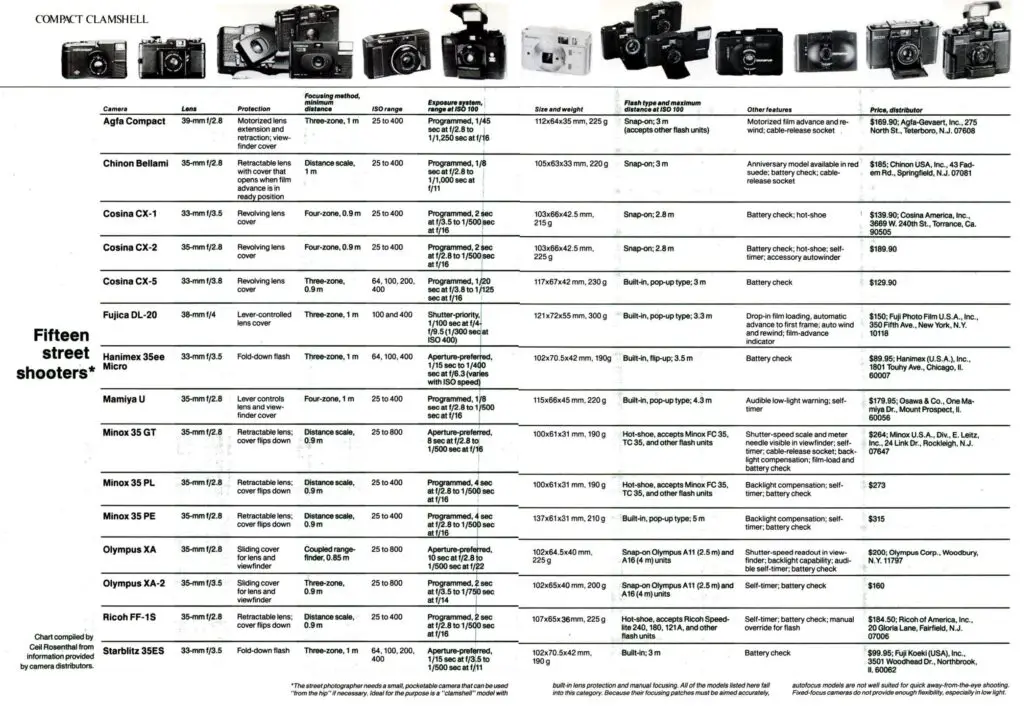

The formula Olympus and Chinon both chose for their new compact cameras clearly hit a chord with consumers as over the next couple of years, a huge number of similar cameras were released by a large number of companies like Agfa, Cosina, Fuji, Mamiya, Ricoh, and others. Although each camera took their own unique spin on the overall design, most followed the same basic template using a semi-wide angle f/3.5 or f/2.8 lens, auto exposure, manual focus, and with some type of removable flash module.

The Chinon Bellami was successful and spawned an anniversary model which came with a red suede body covering and gold logo on the front door, otherwise the camera was the same. In addition, the Bellami was also sold by the German retailer Photo-Quelle as the Revue 35 CC. Other than some cosmetic changes, the two cameras are identical.

I could not find any period reviews of the camera, but that it can be found for sale new in back of magazine camera store advertisements for at least until 1984 suggests the camera sold well, encouraging the company to keep making them. I could not find any specifics about when the camera ended production, but in 1989, Chinon would reuse the Bellami name in a completely unrelated and all new model called the Chinon Bellami AF. As the name implies, this version supported auto focus, but other than the name, shared nothing else with the earlier manual focus version.

Chinon would continue producing inexpensive cameras throughout the rest of the 1980s and into the 90s, but would increasingly become an OEM manufacturer. Less and less models would carry the Chinon name and none would have any innovative features or design. While the Bellami is hardly a prestige camera, it was well designed, easy to use, made great images, and was affordable. Clearly the company was on the right track making good cameras for cheap, but why they lost their relevance over the next decade is a mystery to me.

Today, compact point and shoot 35mm cameras are making a comeback. Some run of the mill models inexplicably sell on the used market for way more than they did a couple years ago, and while I don’t think the Chinon Bellami is a hot ticket item yet, I think that if there was a 1980s point and shoot that should become desirable, this is it. This is a cool looking and easy to use camera with a great lens and just the right amount of simplicity and functionality to give you decent shots, no matter how you try to use it. Even before shooting the camera, I can easily recommend the Chinon Bellami, and who knows, maybe after I post this review, prices on it will skyrocket too!

My Thoughts

Who doesn’t love small cameras? I had always known the Chinon Bellami was a compact camera as many references to it online compare it to models like the Olympus XA series and the many iterations of the Minox 35 series, but it is not until you see the camera that you realize how tiny it is. Side by side with an XA, the two cameras are identical but the Olympus’s taller top plate gives it the illusion of a larger camera. From front to back, the collapsible lens of the Bellami is comparable to a Minox 35 GL I had sitting nearby. Each of these cameras are regarded as very good, compact, full frame 35mm cameras, so I was eager to see how the “discount” Chinon compared.

The Bellami has a metal and plastic body that is covered by two thin plastic barn doors, almost like a toy version of the Voigtländer Vitessa rangefinder. The thinness of the front doors doesn’t exactly suggest the highest build quality, however the metal film compartment door does add a bit to the rigidity of the body. Excluding the barn doors, the camera feels solid and does not creak when handled normally. Weighing only 228 grams (without the flash), the size and weight of the camera is small enough that it easily fits in a front shirt pocket or the front pockets to a pair of jeans. With the attached wrist strap, you could handle this camera all day with little effort, allowing it to dangle from your wrist. With the barn doors closed, the glass lens is protected from bumps and dings as you go hiking or walk around with your kids at the zoo.

There are a couple variations of the Chinon Bellami, some with a red suede body covering and a strange embroidered horse and carriage on it. In every version of the camera, it originally came in a custom clam shell case with the optional flash also included. I was fortunate to find this camera with everything still included, I very much like the design of the all black version as I feel the red suede version looks a bit tacky, adding an additional element of cheapness to the camera.

Up top. the camera has many of the same controls you’d expect on a manual focus camera of its era, just smaller. On the left is a rewind knob with fold out handle. Lifting up on the handle unlocks the rear film door. In a raised portion in the center is the green battery check light and a small window for viewing the selected ASA film speed. Speeds are changed via a tiny wheel to the right of the window. A total of 5 speeds from ASA 25 to 400 are available.

To the right is the automatic resetting exposure counter and cable threaded shutter release. With the lens extended, a half press of the shutter release will illuminate the green battery check light if there is sufficient battery power. Finally, on the far right is a stubby film advance lever which doubles as a mechanical release for opening the front of the camera. Pressing forward on the handle retracts the lens and shutter, and closes the barn doors. Pulling back on the handle opens it. A moderate amount of force is required to open and close the camera, preventing accidental opens and closes of the camera. The action of opening and closing the camera using this lever is very cool, and one of my favorite parts of the camera.

The base has a rewind release button, sliding door for the battery compartment, and a 1/4″ tripod socket. Having a tripod socket on such a small camera isn’t something that is likely to be used often, especially when there’s no self-timer, but with a minimum 1/8 second shutter speed, can be useful in low light conditions where external stabilization is necessary.

Like most compact cameras, there’s little to see on the sides. The left side is where the accessory Bellami flash connects to the camera. A threaded hole and 4 round electrical contacts are use to communicate between the body and flash. On the right is a strap loop for the included wrist strap. There is no ability to connect a traditional neck strap to the camera, not that you’d ever need it.

Around back is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder a small red LED which lights up at shutter speeds below 1/60 seconds. On the main part of the body is a metal plate saying Made in Japan plus the camera’s serial number.

Lifting up on the rewind lever opens the right hinged film door, revealing a film compartment which looks like most other film compartments, just smaller. Film transports from left to right onto a multi-slotted plastic take up spool. From within the film gate you get a peek at the fabric bellows that extend when opening and closing the camera. Inside the rear door is a large metal film pressure plate which is covered in divots to help reduce friction as film transports through the camera. Along the top and bottom edges of the rear door are thick foam light seals which on this camera are showing signs of degradation, and although I was able to shoot the camera without replacing them, it is still something I would recommend doing as all examples of these cameras are approaching half a century old.

When looking down upon the top of the camera with the lens extended, you see two sets of distance markings in meters and feet on the lens. All of the numbers are printed in white except 10 feet and 3 meters which are in green, indicating an ideal “group” distance for shots maximizing depth of field in good lighting. You can skip focusing the camera outdoors at these distances assuming your subject is not too close or at infinity. Despite the Bellami being a manual focus camera without a rangefinder like the Olympus XA, achieving in focus images is very easy, and not the problem it might seem for anyone who has never used one before.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical design with Albada type frame lines visible. The frame lines offer no parallax correction as the camera is so small, parallax is not an issue, even at minimum focus. I am able to see all four frame lines even while wearing prescription glasses. Aside from the slow shutter warning LED on the outside of the viewfinder, there is no additional information about the cameras status visible from within the viewfinder. Not even one of those oval circles in the center of many point and shoots to indicate where the metering system will take a reading of. This particular camera’s viewfinder had a good amount of haze, but I found it to not be an issue while shooting it due to how bright the viewfinder is.

The Chinon Bellami is extremely small, which is great for portability, but required a compromise in its design where there isn’t any room for a built in flash. For the designers of the Bellami to have added a flash, not only would there need to be physical space for the flash, but that flashes require more power than the tiny SR44 Silver Oxide batteries could provide, adding a flash would have required a larger battery compartment, dramatically increasing the overall size of the camera.

Not willing to lose the advantage of a small camera, the designers at Chinon took a similar approach to what a number of other companies like Olympus and eventually Canon and Minolta did, by creating a removable flash module with its own battery compartment. Included in the sale of the Bellami was the Chinon Auto S-120 flash, a small electronic strobe powered by a single AA battery. The flash module screws into a threaded hole on the left side of the camera which also has electronic contacts eliminating the need for any type of sync cable. When mounting the flash to the camera, the aperture is fixed at f/4 and the camera changes shutter speeds based on the focus distance. The flash has a guide number of 12, and can illuminate objects as far as 20 feet away with ASA 400 speed film. Even with the flash mounted, the camera is still small, no wider than a modern day smartphone.

The Chinon Bellami is equal parts cheap and advanced, with an uncommon combination of auto exposure and manual focus in a compact body. The camera has very few frills and just does enough to do one thing well, which is make easy to capture moments that look good on film. The Bellami may not have won many awards when it first came over, but in the years since its release, has garnered a reputation among collectors and film enthusiasts, giving it new life which people in 1980 when this camera was first released, likely would not have predicted. But is this compact camera’s current reputation deserved, or is this another example of people simply overhyping something and paying more for something than it is worth? Keep reading…

My Results

I was pretty eager to shoot the camera in a way which was consistent with how original owners likely would have used it, so I took it with me on a family trip to a local amusement park. As fate would have it, I would shoot the camera twice, once with color and once with black and white film, both at the same amusement park, just on different trips. I didn’t intend on doing it this way, but the opportunity presented itself that way, both times. For color, I used a fresh roll of Fuji Superia 400 and the black and white was bulk Kodak TMax 100.

I had read some reviews of this camera from other bloggers and people whom I know had one and consistently heard praise for the image quality and ease of getting nice looking images, so I kind of knew what to expect when I saw the first rolls come out of the development tank, but I was not prepared for exactly how good.

Of the first two rolls I shot, every single image was not only properly exposed, but also properly focused. That this is a 44 year old electronic point and camera, yet its metering circuits and shutter is still performing at a top notch rate is remarkable. In addition, my ability to get entire rolls of properly focused images without a rangefinder or any other type of focus aide, further cements my assertion that people should not be scared of rangefinder-less cameras.

The images from the 4-element Chinonex 35mm f/2.8 lens were very sharp, showing excellent contrast and accurate colors on both rolls. The most noticeable anomaly was a strong amount of vignetting and some softness in the corners, but nothing that took away from the overall appeal of the images. Although a 4-element in 3-group design, I am unsure if this a Tessar-based design, but I feel like the amount of vignetting suggests it is not, yet I still find the images to have that certain vintage characteristic that many Tessar lenses provide. Regardless of the formula, Chinon’s choice of this lens, in this camera, with this combination of features, was a smart move.

Using the camera was a snap, and while I didn’t plan for it when loading film into this camera, my decision to shoot both rolls at a theme park with a family in tow ended up being the perfect use for the Bellami. The camera was very compact, it fit nicely into my front shorts pockets, it was unobtrusive and fast while shooting, the metering was perfect, and as long as I didn’t attempt any closeups at minimum focus, I was able to keep the lens set to the green zone focus setting for almost the entire roll.

I did not use the Auto S-120 flash at all during my first two test rolls as I was never shooting it in a location where I needed it, but I have shot a number of early 1980s point and shoots with flashes of similar specification and can comment that they usually work well enough to capture objects in low light, often at the expense of backgrounds which have the appearance of a black void. I’ve never found flash photography on point and shoot cameras to be very appealing to me, so it is not something I like to do often, but your mileage may vary.

The Chinon Bellami was true to its promise as an easy to use compact point and shoot, so I don’t have any complaints about it. If I had one nitpick, it would be the design choice for the front barn doors. While cool looking, and I did appreciate the action of opening and closing them with the film advance lever, they just feel and look cheap. In addition, I found that the two doors would interfere with each other while closing, sometimes the incorrect one overlapping the other. I noticed that on my particular example, there was a slight crease in one of the doors near the hinge, suggesting it took a fall or some other kind of abuse at some point in the past. While it still did its job, it is clear that Asahi’s decision with the Pentax to cover the lens via a sliding door was the wiser choice.

Beyond a cheap feeling front door, the Chinon Bellami is a winner. Often times with simple cameras, some people will suggest “this camera would have been better if this or that…” and for me, the camera is perfect (except for the cheap barn door). I don’t mind that it doesn’t offer manual exposure control, or that the viewfinder doesn’t have more information, or that it doesn’t have a rangefinder. The Bellami is the perfect snapshot camera for taking the family to an amusement park. I know, because I did it twice!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Chinon_Bellami

https://oldcamera.blog/2018/01/12/chinon-bellami/

https://www.analog.cafe/r/chinon-bellami-ohrq

https://www.35mmc.com/23/05/2019/chinon-bellami-mini-review/

https://www.brennanprobst.com/2020/11/spotlight-chinon-bellami.html

I really like these for lending to friends who are going on trips! I just tell them leave it at the green focus mark and go. It always gets some fun results, and you can find them for $20-40 so if they get damaged it’s no big deal. I’ve had three and I’ve never gotten one with any problems other then light seals and the barn doors occasionally being a little wonky.