In the early days of still photography, the idea of a variable focal length lens was fantasy. Since the dawn of photography, lens designers, engineers, and mathematicians worked at calculating optical formulas to correct for astigmatism, coma, spherical aberrations, and a vast number of other optical anomalies in lenses of a single focal length.

John Henry Dallmeyer, Ernst Abbe, Paul Rudolph, Dennis Taylor, and Ludwig Bertele are just some of the names of people who created innovative lenses which added features or corrected for anomalies not previously done. Each time a new lens formula was computed and successfully built, future lens designers would build upon the lessons learned on previous lenses, to make something even better.

By the early mid 20th century, many of the world’s most successful lens formulas had already been created. Lenses like the 4-element Tessar are still in use today and provide the basis for lenses found on many inexpensive cameras and those found on smartphones. These lenses were certainly good, but they all had one limitation, which was they only worked at a single focal length. Once your lens was mounted to a camera, if you needed to change the amount of visual information present in your composition, you needed to physically move the camera.

The idea for a variable focal length lens had been proposed as far back as 1834 when early patents were applied for use in telescopes. The challenge with making any lens is that the math needed to correct for optical anomalies only works at a single focal length. When you change that focal length, you need to change the makeup of the lens by physically moving one or many individual elements within a lens. These early examples of variable focal length lenses were crude and had a significant negative effect on the performance of the lens, as we didn’t yet have an understanding of how to correct for all known optical aberrations at multiple focal lengths.

Note: The term ‘zoom’ wasn’t used in the early days of variable focal length lenses, but for the remainder of this article, I will use the term ‘zoom’ since it is easier to keep typing than ‘variable focal length lens’.

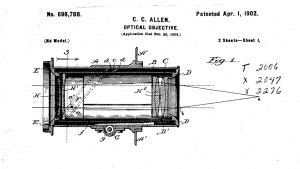

In 1901, a US patent would appear by someone named Clile C. Allen of Chicago, USA who proposed the idea of a lens with moving elements which allowed it to change its focal length. This patent is often cited in books and online as the first real evidence of a zoom lens, however no such example has ever been found, suggesting that the patent was based in theory only and no one had been successful at making one.

The first real evidence of an early Zoom lens is in a 1927 movie by Paramount Pictures showing a scene in which a single shot changes focal length in a single take. The technology behind this lens is credited to a Paramount employee named Joseph B. Walker who created what he called a “traveling telephoto” lens.

In the YouTube video below, you see what is likely the first ever use of a Zoom lens in a motion picture, from the 1927 silent film, “It” starring actress Clara Bow.

Over the course of the next couple decades, zoom lenses would remain a niche product. Their complex design required a huge amount of effort to build, and poor performance compared to prime lenses meant that still photographers likely had little interest in them. Because a lack of extreme sharpness is easier to hide in a moving picture as opposed to a still photograph that could be enlarged, meant that the only advancements at this time were in cinema and later television lenses such as the Bell and Howell Cooke “Varo” 40–120mm and the Rank Taylor Hobson VAROTAL III television lens.

The first significant advancement of a varifocal lens for still photography was the Zoomar 36-82mm f/2.8 lens. The Zoomar was created by an Austrian engineer named Frank Gerhard Back, and is based on an earlier television lens he created around 1947.

Back’s design was revolutionary, creating a system where 4 of the lens’s 14-elements and 2 of its 11 groups move from 36mm to 82mm. A modest 2.3x range from 36mm to 82mm meant that the lens could retain a reasonable speed of f/2.8, good image sharpness, and that optical anomalies could be kept to a minimum, something earlier varifocal lenses couldn’t do. The use of the word ‘zoom’ likely came as a result of the Zoomar name and would be how future varifocal designs would be known by.

A version of the Zoomar would not be produced for still photography until 1959, when the German optics firm run by Heinz Kilfitt would build the lens, initially under contract with Voigtländer for their Bessamatic SLR, but would later make the lens with Pentacon (M42) and Exakta mounts. The Bessamatic’s Deckel bayonet mount is almost identical to the Deckel mount used on the Kodak Retina Reflex, so although the lens was never officially offered for Kodak’s SLR, it could easily be modified to fit on that camera as well.

When it was released, the Bessamatic’s Zoomar was a revolutionary success. For the first time, still photographers could achieve both wide and long focal lengths without changing lenses. Although the Zoomar’s performance was not on par with dedicated prime wide and telephoto lenses, its flexibility more than made up for the disparity.

Over the next 15 or so years, more and more optics firms slowly released their first zoom lenses. Carl Zeiss, Nippon Kogaku, and a few others improved upon the optical performance of the Zoomar, but only marginally. The flaw with how zoom lenses were constructed was that in order to move the elements, a helical, not unlike the helixes used for focus controlled the movement of a group of elements within the lens itself. Each time any piece of glass inside of a lens is moved, the light path is changed, adding back in unwanted optical anomalies that lens designers had spent the better part of a century trying to avoid. The math needed to account for not one focal length but many was extremely complicated.

When Nippon Kogaku released their first commercially available zoom lens, the Zoom-Nikkor Auto 43-86mm f/3.5 lens in February 1963, it was heralded as a massive achievement as its 9-element in 7-group design was optically superior to the Zoomar and other early zooms, but its limited 2x reach and relatively slow maximum aperture of f/3.5 was not ideal. While good for its time, this lens was quickly outperformed by later zoom lenses, and by today’s standards is considered to be one of the worst performing Nikkor lenses ever made.

Like with the development of early prime lenses, as each new zoom lens was released, optical engineers learned how to improve later designs. In addition, the increasing use of computers helped speed up the complex math which previously was done by hand on paper. The optical performance of zoom lenses from the late 1960s and into the 1970s got better, closing the gap between the optical performance of a single focal length lens and one with variable focal lengths.

Although zoom lens performance was improving, the basic design of these new lenses used the same basic concept as earlier designs conceived by Clile C. Allen, Joseph Walker, and Frank Gerhard Back wherein groups of optical elements are moved forward and back using a helical inside the lens. The problem still remained that each piece of glass can only bend light a certain way, and while the math was improving, there was always going to be compromises either on the long (tele) end of the zoom, or the short (wide).

In the early 1970s, engineers at Minolta decided to try a new approach. Rather than slide groups of lenses using a helical, what if there was a way to move individual elements using a gearbox, similar to that of an automobile’s transmission? Such a lens would avoid the compromises needed of a traditional zoom lens because at every focal length, each piece of glass within the lens would always be at the perfect distance to properly focus light with the least amount of optical imperfections.

Bad News: Sadly, in my research for this article, I could find absolutely no historical information about the development of Minolta’s “gearbox” lens. While we know that the lens was completed and went on sale in 1975, I found nothing about its development, who created it, or even what the photographic press had to say about it. Sadly, my reference material from around 1975 and 1976 has holes, so it is possible articles out there exist for it, but I have been unable to find anything. If anyone reading this article has any printed reference material from this era which gives more background info about the development of the Minolta gearbox lens, or even period reviews of it, please let me know!

Minolta’s gearbox lens would go on sale in December 1975 and would have a limited zoom range of only 40-80mm, but would have a relatively fast (for a zoom) maximum aperture of f/2.8, but most importantly, avoided most of the comprises that competing zoom lenses had, delivering extremely sharp images with little to no optical compromises.

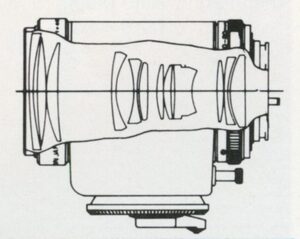

The Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 lens was a strange looking lens with a cube shaped gearbox with both a large dial for focus and a handle for zoom sticking out of one side of the lens. The lens still used a helical for focus, but inside the box were all of the mechanical gears and other bits that allowed the lens to do its magic. Tests of the lens at various focal lengths produced results consistent with prime lenses of matching focal lengths.

An additional benefit to the lens is that Minolta engineers also found a way to add macro capability to the lens. Since they were already moving lens elements around inside the gearbox, an additional lever was added which when activated would shift the focus range to allow for a close focus distance of 15 inches or 37 cm.

The very high image quality combined with a fast maximum aperture and close focus ability meant that the Zoom Rokkor had no competition. This lens performed at a level that no others could. The biggest downside? The price.

The lens had a 12-element in 12-group design but the complexity of the gearbox meant that it took a lot longer to build and required far more individual parts than a normal zoom lens would require. Normal zoom lenses were much simpler, could be built faster, and most importantly, sold cheaper.

Is is Really a Gearbox? Although this review, and most online refer to the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 as having a “gearbox”, in reality, there are no gears in there, rather a series of sliding tracks, levers, and pins that move the lens elements around.

Two versions of the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 were created. The first is an earlier “MC” style lens which lacks support for later models with Programmed AE support. The second was released in November 1977, which was an upgraded “MD” model that supported exposure modes on newer cameras. If you had an earlier MC lens and mounted it to a later body like an XD11 or X-700, you could still use the lens, but only in manual or Aperture Priority AE modes.

I could not find any production numbers for either version of the lenses, but that they were produced for at least two years suggests that at least a decent amount were sold.

Today, the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 is a bit of a cult lens, both for its unique design, but also its excellent performance. Back in the 1970s, our understanding of how to make lenses was still limited to the speed and accuracy of the calculations that made up each element in a lens. As computer technology improved, our ability to refine and improve lens designs is why we are able to produce zoom lenses with excellent image quality, without having to rely on such a complicated design. A quick online search today produces fast lenses with focal lengths never before seen in the 20th century, and each of these designs would not be possible without modern technology.

Still, it is a fascinating look back at a time when in order to make something different, we had to do something different, and for that, the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 is a wonderful lens to play with. Of course, this wouldn’t be a review without some sample images, so this first gallery shows some test images I shot using the lens mounted to a Minolta XE-7, a camera that was around at the same time this lens would have been sold new.

Since it is more likely that someone who might seek out this lens today is going to want to adapt it to digital, I mounted the lens to my Sony α7 II digital mirrorless using a Minolta to Sony E-Mount adapter and shot some photos digitally. Here are those images with slight amounts of post processing in Adobe Photoshop.

Whether you look at the images I got on film or digital, one thing that is certain is this lens definitely stands apart from other 1970s zoom lenses in terms of image quality. In the images I shot, I did a pretty even mixture at 40mm, 80mm, and some in between. I also experimented with the macro mode, taking close up photos of flowers and a few other things.

Although the lens has only a 2x zoom, this range was not that uncommon in the early days of zoom lenses. Other early zooms like the Zoom-Nikkor 43-86mm f/3.5 lens were chastised for softness and undesirable optical artifacts. As zooms got more capable, they were usually designed to have a “sweet” spot in which the lens performed best at a certain focal length, but then would get worse the farther away you got from that sweet spot. Results were certainly acceptable with those lenses, but some compromises had to be made.

Compromises certainly exist with the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8, but not in terms of optical quality. I was very impressed with the sharpness and image quality of the images, especially those shot on digital in which the 24 Megapixel sensor in the Sony α7 II clearly out resolved the film by a significant margin.

In the image above I show a 1:1 crop of the underside of the Mackinac Bridge. I am standing on the southern shore looking under the bridge in this angle, yet you can clearly see the bridge supports and shadow details at a distance of about half a mile away. The resolution is incredible for any lens, let alone a zoom lens from the 1970s.

It is easy to see the appeal of Minolta’s “gearbox” design in which individual lens elements can be moved as needed to alter the focal length of the lens without compromise. In fact, I would argue that calling this a zoom lens is an injustice. It is more like a variable focal length prime lens in that it exhibits the same behavior of a prime lens in the range of 40mm to 80mm.

Clearly, the designers of the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 succeeded at proving to the world that a zoom lens could make wonderful images, yet the design of this camera was never repeated beyond this one model. The reason for this is that the lens is internally complex, difficult and expensive to make, and quite simply sucks to use.

The control layout of the side mounted gearbox is awkward, and despite handling this lens quite often while shooting film and digital, I never once got the hang of it. The controls went against every fiber of my being and regularly caused me to confuse focus and zoom. In addition, the macro mode lever, while a feature I appreciated, also caused me fits while out shooting. The lever itself is rather stiff and moving the lens in and out of macro mode is not smooth as you can feel internal parts of the lens shifting around inside. It is possible that with a lot of use, I would have eventually gotten the hang of it, but I suspect switching back to a more normal zoom and then back to this lens would have required a re-familiarization with the lens every single time.

Goofy ergonomics aside, the complexity required to get “only” a 2x zoom would have likely been exponentially more complex if anyone had hoped to extend the range to 3x and beyond. I could not image what a 35mm – 135mm zoom or even a 18mm – 300mm gearbox zoom would have looked like.

As a proof of concept, the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 is an awesome piece of history and one I am very glad to have in my collection. It looks cool, it has a great story, and it makes amazing images. It is just so impractical and awkward to use, despite its strengths, it is not a lens I’ll likely ever use again.

If you like quirky cameras and want to expand into quirky lenses, I cannot think of a better lens than the Minolta MD Zoom Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8, but if you really think you want a vintage 1970s experience, there are far better options that while might not be as optically excellent, are good enough that their simpler ergonomics will more than make up for it.

I’ve been fascinated by this lens for years but have never owned one. Thanks for your usual thorough and enjoyable review. Here’s what the lens mechanism looks like inside:

https://www.lensrentals.com/blog/2017/09/the-minolta-40-80mm-f2-8-gearbox-zoom-the-clockwork-lens/

I have a question that I haven’t seen answered anywhere else… does the filter thread rotate when focusing or zooming?

Dave, I just checked my lens and I can confirm that the filter ring does not rotate either when focusing or zooming the lens. It just moves forward and back a little.

Thanks, Mike. I can add the lens to my (disappointingly short) list of standard zooms that play nicely with polarising and graduated filters… There’s the Olympus OM Zuiko 35-70mm f/3.6, some Leica R models and several Kiron and Kino-made varifocals, but otherwise few to choose from.

You forgot the Pan cinor released in 1950, the first cinema zoom manufactured industrially by Som Berthiot, ancestor of photo zooms, produced for 20 years and produced 100,000 copies without rivals until the end of the 1950s. Som Berthiot also incorporated a continuous reflex viewfinder inside the Pancinor on certain models. Its creator is Roger Cuvillier, there is an interviewer of Cuvillier https://youtu.be/BlIePHSbM04?si=R4-31kMljWLve0Tk It is angenieux who created the word ZOOM.

Thank you, Mike, for turning from cameras to lenses as subjects of your reviews. Vintage lens collectors and users know that it is the lens which creates the character of an image, whereas the camera itself is mostly just a light-tight box on which to mount that lens. More of these, please!

I appreciate the feedback and I am happy you enjoyed this one, but lens reviews is just not something I have a desire to do. I have one more lens article in my head I’d like to do showing three unique lenses for the Exakta, but digging into the histories of lenses is a lot harder than cameras, plus, I don’t think I am the best person to properly talk about the optical qualities and objective performance of lenses. There are many people out there way more qualified/talented at this than I.