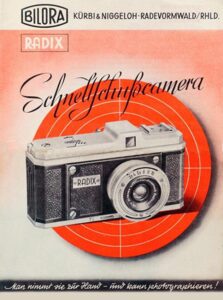

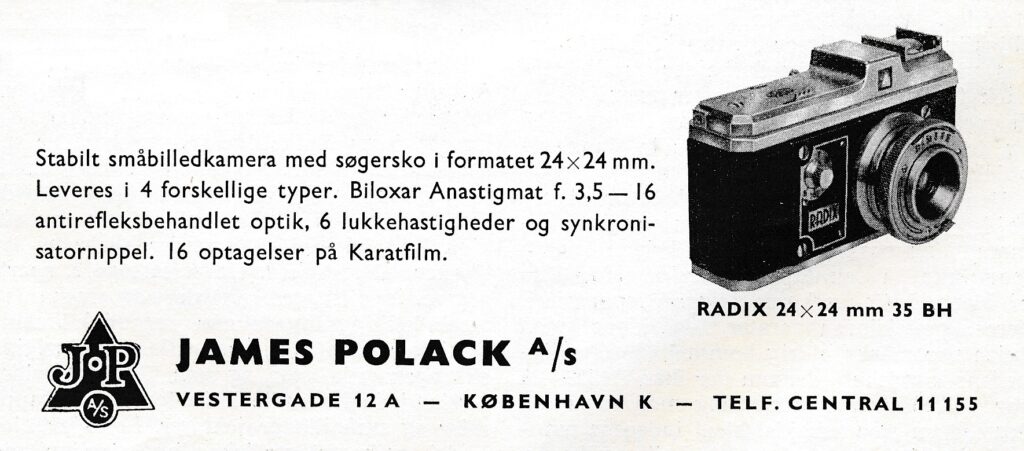

This is a Bilora Radix 35 BH, a simple scale focus camera made by Kürbi & Niggeloh of Radevormwald, West Germany between 1948 and 1952. The Bilora Radix shoots double perforated 35mm film loaded in Agfa Karat cassettes. Marketed as a competitor to Kodak’s type 135 daylight loading cassette, Karat film cameras transport film from cassette to cassette without any ability to rewind film. The Bilora Radix was one of the only cameras to use this film not made by Agfa and was produced in a large number of variants. Most Radixes came with a single speed shutter and an anastigmat f/5.6 lens, but this version had an upgraded f/3.5 triplet lens and a 5 speed (plus Bulb) shutter, controlled by a knob on the front face of the camera.

Film Type: Double Perforated 35mm Agfa Karat Film, 24mm x 24mm Exposures

Lens: 38mm f/3.5 Biloxar Anastigmat coated 3-elements

Focus: 1.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Glass Viewfinder

Shutter: Spring Tensioned Rotary

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/200 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None, with M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 462 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Bilora Radix series were the first 35mm models with the Bilora name, but used Agfa’s Karat cassettes instead of Kodak’s type 135 cassette meaning that film must be hand loaded into empty Karat cassettes. Beyond that, the Radix shoots like any other simple camera, with good ergonomics, simple operation and delivers better than expected results. I shot two models, one each with a f/5.6 and f/3.5 lens and both produced sharp images with some vignetting and low contrast, likely due to the uncoated optics. This is a fun camera to shoot and worth checking out if the price is right. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.1 | ||||||

History

Bilora is a German company with a long history as a maker of tripods, flashes, backpacks, and other photographic accessories. They have long since abandoned actual camera production, focusing entirely on the accessories market.

Bilora is a German company with a long history as a maker of tripods, flashes, backpacks, and other photographic accessories. They have long since abandoned actual camera production, focusing entirely on the accessories market.

The company can trace its roots back to 1909 when it was founded by Wilhelm Kürbi and Carl Niggeloh as Kürbi & Niggeloh. The company started in almost the same industry as they continue today, making accessories like tripods, stands, and other similar products like hat and sheet music stands. They seemed to have almost immediate success as by 1911, they expanded into a new warehouse in Radevormwald where the current company headquarters still remains.

According to Bilora’s archived 2018 website history page, in 1919 the company would begin using the brand name “Bilora” for it’s products. The name Bilora was made up of the letters of the names KürBI NiggeLOh and RAdevormwald. It is unclear when the company officially stopped using the name Kürbi & Niggeloh, but it was at least after the 1950s. For the purposes of this article, I will refer to them officially as “Bilora”.

Bilora would continue to be a leader in the tripod and photo accessory industry until 1935 at which time they would release their first camera, a simple box called the Bilora Box. Like most box cameras, the original models were made of stamped metal, and had simple meniscus lenses and single-speed shutters. There was nothing particularly advanced or innovative about Bilora’s cameras, so perhaps they were sold to accompany their tripods.

Camera production would be interrupted at the onset of World War II, and would not resume until 1946 at which time, Bilora would expand their box camera offerings to many different variants, all using the Bilora Box name. Collectors have assigned names such as Box 1, 2, 3, etc to their names as there seemed to be a lot of different versions available. It was also at this time, that Bilora began the practice of manufacturing cameras for sale by other companies. One of the first instances of this was for the American department store chain, Montgomery Wards, who sold a Bilora made box camera called the Wardette. Over the years, Bilora would make cameras for Voigtländer, Gevaert, ANSCO, Yashica, and several others.

In 1948, the company would venture into the world of 35mm cameras with an all new model called the Radix. For reasons I was not able to discover, rather than build a camera that used Kodak’s type 135 cassette film which was at the time the most popular form of 35mm film, the company instead chose Agfa’s Karat cassette system. Agfa would first release Karat film in 1936 along with their own lineup of Karat cameras. Karat film was loosely based on a similar film system first used in 1927 by Ansco in their Memo camera. Agfa, who had a partnership with Ansco, would release their own Memo film camera in 1938. Both Karat and Memo film used double perforated 35mm film, just like Kodak, however instead of a single cassette that can be rewound, the film transported from one cassette to another without any need to rewind. The Karat film system was much simpler and cheaper to produce, although it was limited to no more than twelve 24mm x 36mm exposures per roll.

Why in 1948, would a new camera be released using a form of film that Agfa themselves was already starting to distance themselves from is unknown, but with the release of the Bilora Radix, Kürbi & Niggeloh would become the only non Agfa company to release a camera to use Karat film.

The Radix would have been seen as an economically priced alternative to more expensive 35mm cameras. Early Radix models were simpler than later ones, with the first model having a single speed shutter and a slow 40mm f/5.6 lens. Only the very first model had a lens marked 40mm, as all later ones were marked 38mm. It is not clear whether the lens was actually different, or whether the difference between 38mm and 40mm was just cosmetic.

Shortly after the release of the Radix, all lenses changed to a 38mm f/5.6 Biloxar and some upgraded models came available with 5-speed shutters and faster f/3.5 lenses. When sold with an f/5.6 lens, the camera was called the Radix 56, when sold with an f/3.5 lens, it was called the Radix 35. Two different f/3.5 lenses, one called the Biloxar and a Schneider-Kreuznach Radionar were also offered and depending on which lens it came with, the ’35’ model number would have a B or and S suffix. Which shutter the camera had also changed the model number too as those with the better 5-speed shutter had an H suffix after either the number 56 or 35. Models with the single speed shutter did not get a letter indicating the shutter.

So for example, a Radix with an f/3.5 Schneider lens and the 5-speed shutter would be called the Radix 35 SH, a model with the f/5.6 lens and the 5-speed shutter was the Radix 56 H, a model with the f/3.5 Biloxar lens and a single speed shutter would be called the Radix 35 B, and so on. Camera-wiki and a few other sites list a model called the Radix A and one called the Radax, but I’ve found no evidence of these models. It is plausible that additional variants exist, but there is so little documentation found about these cameras, I have my doubts.

I found no evidence that the Bilora Radix was exported to the United States nor could I find any information about pricing. Considering the specifications of the Radixes suggest an entry level camera, the prices were probably low, making them affordable to those who couldn’t afford a Leica or Contax. Like most smaller production German optics companies, the Bilora was likely sold in developing European markets or those still recovering from the economic impacts of World War II.

I also could not find any sort of sales information nor a conclusive date which the series ended. Some sources suggest 1951, but that unsold new inventory was available through 1952, the true end date was probably somewhere during that time. The Radixes use of Agfa Karat film which Agfa themselves had already abandoned in the film’s namesake Karat camera certainly contributed to the Radix’s demise, but that didn’t stop Bilora from continuing to make inexpensive cameras.

Throughout the 1950s, Bilora would expand their camera lineup to include many different variations of cheap cameras. One such example was a Bakelite viewfinder camera called the Bilora Boy, which literally was just a black plastic box with a single speed shutter and meniscus lens. Other models in their portfolio would include the Bilora Bella series and others named Bonita and Bellina.

The Bilora Bella series would see some success and remain in production until 1964 at which time the company mainly stuck to inexpensive 126 “Instamatic” film cameras. By this time, a majority of Bilora’s production output was for models made for other companies such as the Zeiss-Ikon Ikomatic, and Yashica Minipak.

Bilora would stop making cameras around 1975 and resume its original focus as a maker of photographic accessories such as tripods, stands, and carrying cases. I hesitate to call Bilora a success or a failure as they have managed to stay in continuous operation for over 100 years and as recently as a couple of years ago are still in the same industry as the one they started in over a century ago. Their cameras never aspired to be more than inexpensive and simple designs, and when found today, usually still work quite well.

My Thoughts

The Bilors Radix is a curious camera, an anomaly among 35mm cameras. Using Agfa’s Karat cassettes in an inexpensive postwar camera either means this camera was behind the times using a format that had already fallen out of favor by the industry, or it was a pioneering camera that was ahead of its time using what would become Rapid film in inexpensive cameras about a decade later.

Whichever way you look at it, the Radix stands alone in the era it was made. This particular example was near the top of the Radix line, featuring a faster f/3.5 Biloxar lens and a 5 speed shutter with speeds from 1/2 to 1/200. Whether you had this one or one of the simpler models, the camera has a reassuring heft you don’t always finds in cheap cameras. With a weight of 462 grams, the camera’s small size combines for a compact and dense feeling camera. The metal body does not creak in your hands, the body covering has a nice feel to it, and the chrome plating shows no signs of flaking off or oxidizing. Despite a small size, the Radix avoids some of the ergonomic snafus of other compact cameras with each of the most important controls in locations that are comfortable and easy to reach.

Up top, we start off with a simple accessory shoe which can be used for an auxiliary rangefinder or flash if you so choose.

A hump for the optical viewfinder is next, and on the right side of the camera is an engraved Bilora logo flanked above and below by the shutter release and exposure counter. Unlike most cameras, the shutter release is not a button, but rather a sliding lever with a serrated top. Firing the shutter is done by resting your finger on the release and sliding it towards the right side of the camera. While unorthodox, this works quite well and fires the Radix shutter with a satisfying ‘ka-chunk’. The location of the shutter release is in the exact location where my right index finger naturally wants to rest while holding the camera. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made on the current roll of film from 1 to 16, but strangely offers no way to reset. I suppose that with the use of Karat cassettes which cannot be rewound means that after shooting a complete roll, the counter should always be in the correct position to start a new roll, but if you ever were to shoot a short roll and need to reset it back to zero (actually an ‘A’ position), you need to repeatedly fire the shutter until it gets back to the beginning.

The base of the camera offers only a metal 1/4″ tripod socket and four large screws which I assume hold the camera together. On the plus side, the location of the tripod socket is in the center of the camera’s weight, which would improve balance while propped up on a stand.

The sides of the Radix are rather symmetrical with angled corners on both sides. On the left, the edge of the top plate has two flash sync ports, one for F-sync and the other for X-sync and a small engraving that says “Made in Germany”. Only models with the “H” shutter have an X-sync port. Models with the single speed shutter only have a single sync port for flashbulbs. On the right, the edge of the top plate has a threaded cable release socket for a remote shutter release or one of those auxiliary self-timers.

Around back, next to the small circular eyepiece is the film advance lever. Moving the lever from left to right advances the film one full exposure, readies the shutter, and advances the exposure counter one. The movement of this level is firm, but smooth and can easily be done in one swift motion with your right thumb while holding the camera to your eye. With the comfortable location of the shutter release and film advance, the Radix can easily be shot quickly from exposure to exposure without having to lower it from your eye. In the center of the back is a large disk with two raised chrome posts which are used to unlock the rear door to access the film compartment. With the two chrome posts pointing directly up and down, the door is locked, and to unlock it, an approximate 30 degree counterclockwise turn unlocks the door.

The door lifts straight back and does not include the base of the camera. Interestingly, the top and bottom of the door are exactly the same which means there is no wrong way to reattach it back to the camera when you are done loading film. The film compartment resembles most Karat and Rapid film cameras with the biggest difference being the square film gate which provides 24mm x 24mm exposures. Since Karat film stock is identical to Kodak type 135 cassettes, both styles of film need to leave room for both sets of perforations above and below the gate. Film transports from left to right. Although Rapid film would not debut until the 1960s, it is possible to use those cassettes in this camera since they are so similar.

Neither Karat nor Rapid cassettes are designed to be reloaded, but it can be done simply by pushing unexposed film back through the felt light trap into the cassette. The biggest concern with reloading these cassettes is not to push too much film into them as they can easily jam. A normal Karat cassette only had enough film for twelve 24mm x 36mm exposures or sixteen 24mm square images. This ends up being a length of film that is about 15-18 inches long. The inside of the film door has a large black painted film pressure plate and there are no foam or felt light seals anywhere in the camera for you to replace.

Looking down upon the top of the shutter and lens, you’ll see on the inside of the focus ring a distance scale with engravings for 1.5 meters to infinity. The entire motion from minimum to maximum focus is only about a 45 degree turn. This focus scale only appears on Radix cameras with the faster f/3.5 lenses. Those with the slower f/5.6 lenses show no focus distance markings, only an infinity indicator and a black dot which indicates a fixed zone focus distance of about 3 meters. The minimum focus distance is not indicated on the f/5.6 models.

Up front, all Bilora Radix models with an “H” in the model number have a 5-speed shutter with a dial to the left of the lens and shutter for selecting speeds 1/2 to 1/250 plus Bulb. Non “H” models have a single speed shutter with a tab below the shutter with a sliding switch that selects between Instant (indicated by an ‘M’) and Bulb (indicated by a ‘T’). Models with the f/3.5 lens have an aperture selector above and below the lens on the face of the shutter with marks from f/3.5 to f/16. Models with the f/5.6 lens have a small window showing apertures of f/5.6 to f/16 selectable by a tab behind the lens. A small number of Bilora Radixes have a 38mm f/3.5 Schneider Radionar lens, but otherwise work exactly the same as those with the 38mm f/3.5 Biloxar lens models.

The viewfinder is as simple as they come. A straight through optical design, peering through the tiny hole shows a square approximation of what will be captured on film. There are no frame lines nor any attempt to correct for parallax not that there really needs to be as the minimum focus distance is a rather long 1.5 meters. I could not find any specifications for the Radix’s viewfinder but the magnification ratio is quite small, showing a smaller than life view through the glass. This has the positive benefit however, of being able to see all four edges of the frame while wearing prescription glasses.

The Bilora Radix is a surprisingly well put together camera. Build quality feels better than average for an economically priced and simple camera. The ergonomics are quite good, the shutter (on the ‘H’ models) offers enough flexibility to be used in a wide range of lighting situations, and the speed which you can operate the camera means you should have no problem making it through a whole roll of sixteen exposures. If you’ve never handled one of these cameras before, I wouldn’t blame you for dismissing these as cheap cameras not worth your time, but the more I handled the Bilora Radix, the more excited I got thinking about putting some film through it. Would my excitement be warranted or short lived? Keep reading…

My Results

In an early draft of this review, I was ready to put an early Bilora Radix 56 B through its paces for a review. I was fortunate to have two empty Karat cassettes, so I pushed in strip of bulk Kodak TMax 100 and took it out shooting. I had barely started writing that review when I came across a second, more upscale Radix 35 BH, so I postponed the review until I had a chance to shoot it. Originally, I was just going to scrap the shots from the earlier camera, but liked them enough that I thought I would share galleries from both cameras. The first set of images below are from the Bilora Radix 56 B.

For the second gallery, I loaded up the same bulk Kodak TMax 100, for a true apples to apples comparison between two Radixes with the two different lens and shutter combinations. I assumed that the faster f/3.5 lens model with a more flexible range of shutter speeds would deliver improved results.

After comparing the results from both cameras, I was doubly surprised. First, that images from both cameras came out quite nice and better than I expected, but also that images from both cameras showed very little difference.

Sharpness is good in the center with minimal fall off near the edges. Vignetting is evident from both cameras, but not in any way that I found distracting. That the Radix shoots 24mm square images means that some softness that would be farther away from center in a 36mm wide image isn’t visible, but for what is here, I was pleasantly surprised.

Contrast was a bit better, with slightly deeper blacks from the Radix 35 BH, but was still a bit low in both cameras. This could be possibly due to a minor amount of dust and debris present in both lenses, but I suspect the lack of modern lens coatings was more to blame as images where the sky was present showed some haze.

The lack of indicated focus markings on the lesser Radix 56 B didn’t impede my ability to get in focus images. With the markings on the 35 BH, I felt more confident in closeups, but I suspect that depth of field for both was enough for most shooting situations. That I managed to get in focus and properly exposed mirror selfies using two different scale focus cameras is impressive indeed!

Certainly these images aren’t up to par with a higher end Leica or Nikon, but they’re not supposed to be. Keeping in mind that the Bilora Radixes were built for the entry level market, using a film type that was already on its way out the door, and likely sold to novice photographers, I think the results are quite good, and easily comparable to many simpler point and shoot cameras made in the years and decades to come.

I found the ergonomics of the camera to be quite good, with the sliding shutter release very easy to locate with my right index finger with the camera to my eye. I do question the decision to go with a shutter release that requires a horizontal movement as I did notice that in some of my images from both cameras, there was a tad bit of blur. I think that with a more traditional button this might have been avoided, but it is also possible that I just needed to stabilize the camera better.

Perhaps the worst thing about the Radixes is that the series came to an end so quickly. Certainly the decision to use Karat film was a bit part of the camera’s lack of success, but it makes me wonder what might have been had Bilora chose Kodak’s type 135 cassettes from the beginning? I suspect that the camera would have been more appealing in more export countries and possibly had a chance at being sold in the US where sales might have kept it going for much longer, least til the end of the decade.

But then again, that this camera has an unlikely film format and a unique design is what makes it more appealing to collectors. If this was just another entry level 35mm camera, it probably wouldn’t have been as interesting to use. I guess that’s the challenge of being a film camera blogger, sometimes it takes a camera that wasn’t successful to be interesting enough to want to write about! Bilora Radixes aren’t common, but when they are found, they usually don’t have very high asking prices, so if you have a chance to pick one nup, I definitely recommend it. And if your intention is to shoot it, based on my results from ones with the f/5.6 and f/3.5 lenses, there’s not a lot of difference between the two, so I’d say condition and functionality should be the priority over what lens it has.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Bilora_Radix

https://cameracollector.net/bilora-radix/

https://wanderinweeta.blogspot.com/2013/12/we-are-so-spoiled.html

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/other/non-folding.html#radix

https://www.kamerasamling.dk/bilora/smaa%20serien.php (in Danish)

https://www.guenterposch.de/Radix.html (in German)

There were other non Agfa cameras to use the Karat cassettes, the Oehler Infra is one. It shoots 24×24 on karat/rapid film.

Good catch Eric! This proves my point that no matter how hard to try to research, if you say things like “first, last, only, never, etc” there will always be some oddball exception! I’ve never heard of the Oehler Infra, but now I have to look for one!