This is a Gamma II, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Gamma Officine Meccaniche de Precisione in Rome, Italy between the years 1947 and 1950. The Gamma II was the first in a series of Gamma cameras and the only one with a unique bayonet lens mount. Later Gamma cameras switched to the 39mm Leica Thread Mount for greater lens compatibility. The Gamma II has a coupled rangefinder and shutter speeds from 1/20 to 1/1000. A characteristic of all Gamma cameras is the focal plane shutter which consists of a curved piece of metal that is responsible for the two humps on the front of the body. The curved focal plane shutter has the benefit of being impervious to light leaks but has the side effect of being quite loud. Although an uncommon camera built in small numbers, the Gamma series proved to be popular, staying in production for a decade.

Film Type: 135 (35mm) in Special Gamma Cassettes

Lens: 55mm f/3.5 Koristka Victor-Gamma uncoated 4-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Gamma Bayonet

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder and Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Curved Metal Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/20 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Accessory Shoe

Other Features: None

Weight: 578 grams, 400 grams (body only)

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Gamma II is a camera that was built to compete with the Leica rangefinder, but unlike most Leica copies, the Gamma has more things different than the same, including a very unique curved shutter, a different body casting, an inability to rewind film, and a film cutting blade inside the film compartment. Despite these differences, in use, the cameras are very similar, and although this early version uses a proprietary bayonet lens mount, later Gamma rangefinders used the LTM which meant all lenses were compatible. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

History

The years immediately following World War II brought a halt of exported cameras, lenses, and other photographic goods to other areas of the world. In Europe, countries like France, England, and Italy were forced to develop their own products in order to fill demand for new products. For the few German companies who were still making products, trade restrictions imparted extremely high tariffs and other penalties on German goods, making getting anything from Germany almost impossible.

Note: The history of the Gamma camera is not well documented in English. The only two sources for information about this camera come from the book “Made in Italy: apparecchi fotografici italiani” by Marco Antonetto and Mario Malavolti, and from the excellent Italian language website, bencinihistory.altervista.com. The history and the naming of each model varies between the two sources and is very confusing, especially when also having to translate from Italian to English. Most Gamma cameras are engraved only with the “Gamma” name and not a suffix or specific model number, so determining which Gamma you have is not easy. Between the two sources, I lean more towards the bencinihistory website as the amount of information is much more thorough than the book. What follows is my best attempt to piece together and translate what I learned reading both sources.

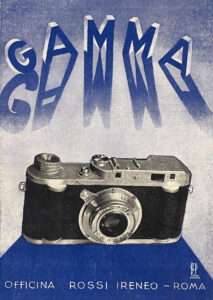

After World War II, with a halt in the availability of imported goods into Italy, a man named Ireneo Rossi would form his own manufacturing company in Rome. Working for him were his two sons, Giuliano and Silvano Rossi, who had an interest in photography and got to work on a new 35mm rangefinder camera which they would eventually call the Gamma.

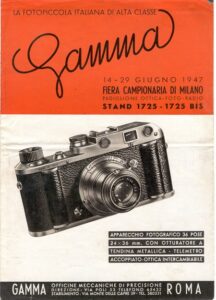

It is not clear exactly when work on the new camera began, but the first evidence of what look to be working prototypes would appear at the Fair of Milan in 1946. Unable to produce their own lenses, the Gamma factory turned to another Italian optics firm, Fratelli Koristka to design lenses for their new camera. It was at the booth for Fratelli Koristka that three camera prototypes were shown, listed in a pamphlet as the Gamma I, II, and III. All three cameras had an interchangeable threaded lens mount with a 55mm f/3.5 Koristka Victor lens and shot 24mm x 36mm images on double perforated 35mm film.

The Gamma I was the base model and was scale focus only, without a rangefinder. It also had a shutter with speeds from 1/20 to 1/500 plus Bulb. The Gamma II added a coupled rangefinder and increased the top shutter speed to 1/750, and the Gamma III added a slow speed governor, extending the slow speeds down to 1 second.

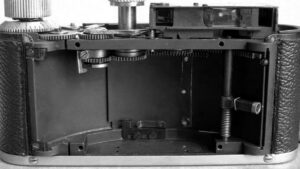

Perhaps the most distinct design of the new camera was its focal plane shutter. Unlike the Ernst Leitz Leica, which at the time was the most well known interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder which used horizontally travelling cloth curtains, the Gamma camera used rigid metal curtains that were curved across the focal plane. The use of metal curtains meant that they would be less fragile and immune from tears or light leaks that could penetrate some cloth curtains. The curved design of the curtains added rigidity to the curtains, further enhancing its durability, but also improving cold weather performance, allowing for reliable operation down to -20 degrees Celsius.

At the 1946 fair, the cameras attracted the attention of a Roman lawyer named Telemaco Corsi who himself was interested in photography and was working on a camera which would eventually be released as the Rectaflex. Corsi saw an opportunity and contacted the Rossi brothers and agreed to a business deal which would create an all new company called Gamma Officine Meccaniche de Precisione in Rome, Italy. Manufacture of the camera would be done at a factory in nearby Magliana.

Work continued on the new Gamma, further improving its design and changing a few things. Of the three prototypes shown in 1946, the Gamma II was the one which evolved into what would be shown a year later at the 1947 Fair of Milan. The square rangefinder windows of the prototype were replaced by round ones, the top speed of the shutter was extended to 1/1000 seconds and the original threaded lens mount was replaced with a new bayonet mount unique to this camera.

New versions of the scale focus only Gamma I and rangefinder equipped Gamma II would officially go into production in September 1947 and would come standard with the 55mm f/3.5 Koristka Victor lens from the 1946 prototype. The only other lens made in the Gamma’s bayonet lens mount was a SOM Berthiot Flor 50mm f/2.8 lens, but no others in any other focal lengths were made.

The bayonet lens mount proved to be unpopular as in 1949, a new model called the Gamma III would be released which had the slow speed governor of the 1946 Gamma III prototype, but retained the 39mm Leica Thread Mount meaning it was compatible with a huge number of pre-existing lenses for the Leica system. For a short while the bayonet Gamma II and thread mount Gamma III were offered at the same time, but within a few short months, the Gamma II was discontinued although some have been found which were modified to use the 39mm Leica Thread Mount. No records for how many were made have ever been found, but according to the bencinihistory website, the highest serial number ever found suggests that around 800 were ever made.

The Gamma III appears to have been more successful, with two variants made, a version unofficially called the IIIA which lacked flash synchronization and a IIIB which did. Although supporting a huge number of Leica lenses, the Gamma III and its variants had a number of lenses designed specifically for it by Koristka, SOM Berthiot, and Schneider, ranging in focal lengths from 38mm to 145mm.

Despite a competitive feature set, good ergonomics, and support for one of the most popular lens mounts in the world, sales of all Gamma cameras didn’t meet expectations. Disagreements between management of Gamma Officine Meccaniche de Precisione and the Rossi family who held the original patents came to an impasse in 1951 and production of the entire lineup ended. Unsold inventory continued to be sold for a few years after, but no other Gamma cameras would ever be made.

At the 1951 Milan Fair, the Gamma Officine Meccaniche de Precisione company would release a fixed lens 35nn rangefinder camera called the Perla. Instead of the Gamma’s unique focal plane shutter, the Perla had a much simpler leaf shutter and came in a more compact body. The Perla sold for less than the Gamma, but saw a moderate level of success, staying in production until at least 1955. A scale focus version called the Stella would be released in 1953 and was sold concurrently with the Perla.

Gamma Officine Meccaniche de Precisione would continue producing inexpensive 35mm cameras throughout the 1950s, but an increase in available of imported cameras from Japan and Germany diluted the Italian camera market to the point where it was no longer economically feasible to keep making them. By 1960, the company had been dissolved, never to make another camera again.

Today, there is a small, but loyal following of Italian camera collectors. Models like the Gamma, Rectaflex, and compact Ducati half frame camera are desirable for their high quality, unique appearances, and obscurity. No Italian camera was ever produced in large numbers, making cameras like the Gamma difficult to find but for the collector who wants a complete picture of the postwar interchangeable lens 35mm camera industry, having a Gamma camera in your collection is a must. For everyone else however, the price may be difficult to justify. Still, these are cool cameras that deserve some recognition by those fortunate enough to own one.

My Thoughts

There are Leica copies and there are cameras that “loosely fit a vague set of parameters that define what a 35mm rangefinder camera was like in the mid 20th century”. The Gamma II falls in the later category. With a body that only resembles the most popular German rangefinder when viewed at more than 10 feet away and with a bit of help from some hallucinogenic mushrooms, the Gamma is more different than it is similar to a Leica, but at the very least, you can see that the people in charge with the camera’s design knew who they’d be going up against when the camera would eventually go on sale.

This Gamma came to me from the collection of Kurt Ingham and is a surprisingly cool camera that I had only ever seen photos of online. The build quality is good, but I can’t help but feel like it is a notch below a German Leica or even a good Japanese copy. There’s an excess of screws all over the body securing various parts of the camera together, the shutter speed selector has some wobble to it as do the two levers for opening the film back and using the film cutter. None of these are deal breakers and could even be symptomatic of a low production 77 year old camera, but there’s no mistaking this for a IIIc.

I do like the camera’s design however, as I love the two bumps on the front plate which help make holding the camera more comfortable than the flat fronts of so many other mid century cameras. I like the design of the exposure counter and that the aperture ring on the Victor-Gamma 55mm f/3.5 lens is controlled by a small lever instead of a ring on the face of the Leitz 5cm f/3.5 Elmar. The leather body covering is peeling in various locations but has not cracked or shows any signs of tearing. The chrome plating has a nice matte finish up top, but is showing some signs of wear on the base plate, suggesting some cost cutting during its application.

Looking down upon the top of the camera, things look very different from a Leica. One very obvious difference is a lack of a rewind knob. The Gamma was designed for cassette to cassette transport only, with no ability to rewind it. If you wanted to swap rolls or develop a roll before you finished it, the camera has a film cutter similar to that of the Ihagee Exakta which can slice the film mid roll. To do this, a small an unmarked lever on the lower portion of the top plate, immediately to the right of the viewfinder does this. Swing the lever out so that it is pointing straight back and then pull up on it until it stops. This lever has a curved razor blade on the other end which will slice the film, allowing you to wind the exposed portion into the take up cassette and then remove it for developing.

Next to the film slicer is another lever with the letters ‘a’ and ‘c’ engraved next to it. The letter ‘c’ means the rear film door is closed or locked, and the letter ‘a’ means it is unlocked and ready to be opened. Above this lever on the raised portion is an accessory shoe. To the right of the show is the shutter speed dial with speeds from 20 to 1000 plus Bulb. The Gamma II lacks any slow speeds below 1/20. You must wind the film advance to tension the shutter before changing shutter speeds or else the correct speed will not line up with the index mark. Changing speeds requires you to lift up on the dial and rotate it. While firing the shutter, it is critical to not touch the shutter speed dial as it rotates while the shutter is moving and any resistance from your fingers will throw off the timings.

To the right of the shutter speed dial is the cable threaded shutter release button. This being the only Gamma I’ve ever handled, I found that the shutter release required a bit more pressure to fire the shutter than I was used to, but otherwise worked fine. Below and to the left of the shutter release is a small window in the top plate that acts as a film transport indicator. As you advance the film, a little black dot will jiggle around behind the window indicating that the film is advancing. This is a welcome feature not commonly found on Leicas or its copies. On the far right is the film advance knob, and in front of it an oval window for the exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing how many exposures have already been made and must be manually reset after installing a new roll of film.

The back of the camera has two small windows in the far upper left corner. The arrangement of the windows is the same as on a Leica IIIa with the coupled rangefinder on the left and the main viewfinder on the right. Below the viewfinder is an engraving that says “Gamma officine meccaniche di precisione – Roma – brev. internazionali”. To the right of the engraving is a knurled wheel which is the exposure counter reset. After loading in a new roll of film, push in on this wheel and spin it with your finger to reset the exposure counter back to ‘0’.

The sides of the camera are symmetrical and only feature a metal strap lug. This is a nice feature to have, especially on an extremely rare and valuable camera so that it can be securely attached to a neck strap while out shooting with it.

The base of the camera has a 3/8″ tripod socket and nothing else. The use of a larger 3/8″ socket is not unusual as the more common 1/4″ size was not widely used by European camera makers until later. If you wanted to mount this camera to a modern tripod today, you’d need to use a 1/4″ -> 3/8″ adapter.

The Gamma’s film compartment takes a cue from the Zeiss-Ikon Contax in which both the back and bottom come off all in one piece. To unlock it, move the smaller lever on the top plate to the ‘a’ position and the entire back and bottom slide off. With the back removed, you get a good look at the curved shutter plane that is unique to the Gamma. It works similarly to focal plane shutters on any other camera, it’s just curved!

Film transports from left to right onto a removable metal take up spool. This Gamma came to me without a spool, so I used a plastic core from a commercial 35mm cassette and it worked fine, other than having to tape the leader to the spool. If you do have a Gamma with an original spool, it is important not to lose it as you’ll need one to load film in the camera. The Gamma was intended for cassette to cassette transport only, as there is no way to rewind film at the end of a roll. The film pressure plate is hinged to the bottom of the camera, folding shut to keep the film flat while it transports through the camera. The Gamma predates the use of foam light seals, so there are no sticky or crumbly light seals to replace if you want to shoot the camera.

Looking down upon the top of the collapsible 55mm f/3.5 Koristka Victor-Gamma lens, you’ll see a fixed depth of field scale closest to the body of the camera. Although the scale looks like it is part of the body, it is actually connected to the lens, so it comes off when removing the lens. I did not have access to any other Gamma lenses, but I suspect those would have appropriate scales for whatever focal length and maximum aperture that lens was capable of. Next is the focus scale with engraved numbers from 1 meter to infinity. The lens has an infinity lock, like most LTM lenses, requiring you to press a button on the handle to move it away from infinity. Next, in the middle of the lens is a curved arrow which can only be seen when the lens is properly extended. The arrow indicates the direction you must pull and twist the barrel to fully erect it. A knurled ring near the front of the lens does not control anything on the lens and is just there to help extend and collapse the lens. Finally, nearest the front is the aperture ring which has a small handle which makes turning it easier. A tiny scale showing f/stops from f/3.5 to f/18 is engraved into the outermost ring. Note that this lens shows an earlier f/stop scale with non standard stops like f/6.3, f/12.5, and f/18.

Up front, to the left and right of the lens are two bumps which function as finger grips while holding the camera, making it more secure, but are actually there to cover up part of the internal shutter mechanism. I assume that whoever designed this camera saw the ergonomically pleasing bumps as a happy accident, rather than a primary design choice.

The Gamma II features a proprietary bayonet lens mount which appeared on only one other camera, the Gamma I from 1947. Every other Gamma camera, including the 1946 prototypes used the standard M39 Leica Thread Mount. Although I found no evidence of this, most likely the people at Gamma realized that they would have much better support for their camera if existing LTM lenses could be used with it, without forcing owners to buy all new lenses. A small sliding button near the 7 o’clock position of the lens is the bayonet release. Press this button towards the lens mount while rotating the lens counterclockwise to remove it. Attaching it is opposite of removal. When looking at a Gamma camera, it is easy to tell whether it has a bayonet or LTM mount by checking for the lens release button. The thread mount cameras had no need for a lens release, making them easy to spot at a glance.

The viewfinder and rangefinder work similarly to their German counterparts with the rangefinder on the left and viewfinder on the right. The rangefinder window has an increased magnification ratio, allowing for better focus accuracy, especially when using longer lenses. For those used to more modern rangefinder cameras that combine the rangefinder patch and viewfinder window together, having to move your eye between two windows might seem like a bad choice, however one advantage to this design is that the rangefinder patch can be much larger than on other cameras, making focusing much easier. I do not know what the magnification ratio is, but an unscientific comparison with a Leica IIIa which I know is 1.5x, looks to be the same.

The viewfinder window has a clever feature in which an arm with a red dot on the end moves up to partially block the viewfinder when the shutter is not set. Turning the film advance knob to tension the shutter makes this arm move out of the way, letting you know the camera is ready to make an exposure. This feature was completely missing in Leicas and most Leica copies, but would reappear in several SLRs later in the 20th century.

In the book “300 Leica Copies”, authors Pont & Princelle often stretch the limits of what a Leica copy should and shouldn’t be. For me, the Gamma II has enough differences that it really shouldn’t be considered a copy, rather more a camera inspired by and built to compete with the Leica. On paper, the two camera systems share a lot in common, but in looks and use, there’s enough different that the people who made this camera deserve the credit for designing their own unique camera, and not another copy.

Copy or not, the Gamma II deserves to be mentioned in the same conversation as a Leica, and people generally really like Leicas, so how does the Gamma II compare? Should Pont & Princelle’s book be renamed 299 Leica Copies or are they justified sticking with 300? Keep reading…

My Results

Excited to give the old Italian camera a try, I went to my cache of film to grab some Italian Ferrania…except I was all out of it. After looking online and becoming shocked at how much Ferrania film has become over the past couple years, I decided against shooting Italian film in an Italian camera and just loaded in some fresh Fuji 200. I figured, if it is good enough for a Nikon, it should be good enough for a Gamma!

This review would make for a good cautionary tale for anyone wanting to use old cameras that “appear” to be working. A camera can look like and make the same noises as a camera that properly works, and might even be able to make it through a roll of film without any catastrophic failures, but it still might not be in a condition that most would call “working”. Things like light leaks, uneven exposure, soft focus, and any number of other ailments can still plague images shot with an old camera that hasn’t been serviced in decades. Such was the case with this Gamma. While my preliminary testing didn’t reveal any major issues, the gallery above from my first roll shows light leaks in nearly every image, a large thick scratch going across the top of every frame, some missed focus, and a general softness to the lens which likely is a result of the lack of modern coating.

Imperfections aside, I was pleased with the images from this strange Italian camera. It is clear that even if this example had been perfectly working, the 55mm f/3.5 Koristka Victor-Gamma lens is a less “perfect” lens then say a Zeiss Tessar or Schneider Xenar lens of the same era would be. That the lens is uncoated definitely shows in the outdoor shots with a general lack of contrast and pop. In hindsight, choosing Fuji 200 wasn’t the best first choice for this camera as I think a high contrast black and white film like Rollei RPX25 or Agfa APX100 would have delivered more pleasing contrast. Still for those who like a more muted “vintage” look the 4-element Koristka Victor-Gamma did a good job. Sharpness was good across the frame, out of focus details were vague but not distracting, and I noticed little to no vignetting near the corners.

When looking at the Gamma’s internal design and cosmetics, it shares very little with a Leica other than being an interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder camera. But even though the camera isn’t built like a Leica, in use, the resemblance is quite strong. Putting aside cosmetics, the location of the separate viewfinder and rangefinder windows, film advance, shutter release, shutter speed control, focus and aperture controls on the collapsible lens very much minick a Leica II or III with a collapsible Elmar. It is clear that the designers of this camera wanted to recreate the Leica experience, while not exactly copying the design of the camera, and for that, the Gamma is very successful.

I might even suggest that the design of the curved shutter, which necessitated the two vertical humps on the front of the camera unintentionally added dual finger grips to the camera, enhancing the grip you have on the camera while holding it. The Gamma predates finger grips like that on the Canon AE-1 and Nikon F3 by nearly three decades. Had the Gamma been a more successful camera, I suspect people would have caught onto this ergonomic enhancement, demanding it on cameras by other companies, even with the Gamma’s strange shutter.

It is clear to me that a lot of thought and love went into the design of this camera, but it wasn’t successful. Perhaps the world wasn’t interested in a low production Italian 35mm rangefinder, or perhaps the reputation of such a little known company wasn’t enough to get the camera any recognition, or perhaps it was something else.

If I were to guess what would have been in the “something else” category, I feel as though the Gamma has two fatal flaws. The first is most obviously the bayonet lens mount. If the Gamma were to have had any chance at survival, it needed to support the same lenses as the Leica did. Gamma Officine Meccaniche de Precisione eventually figured this out and switched to the 39mm LTM lens mount in 1949, but owners of the Gamma II were limited to only two lenses.

A second fatal flaw was its inability to rewind the film. Some very early 35mm cameras from the early to mid 1930s couldn’t rewind their film either, but to miss out on this feature after World War II would have been a dealbreaker for anyone wanting to try out this camera.

Even with support for LTM lenses and the ability to rewind film, I still can’t say whether the Gamma would have been more successful, but at the very least, maybe more would have been sold, making this a less obscure camera to find in the wild. As it is, the Gamma II is an attractive and very interesting camera with excellent ergonomics and a clever shutter that had more time been developed into evolving it, could have possibly influenced shutter designs by other companies.

I enjoyed shooting the Gamma II, even though the images didn’t turn out great. I’ll definitely shoot it again, learning from my experiences with this first roll, hopefully tracking down the light leaks and using a more contrasty black and white film. At whatever time I get some new sample images, I will come back and update this review.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Gamma_OMP

https://www.dpreview.com/forums/thread/4755595

https://www.mprrossi.com/macchina-gamma/ (in Italian)

http://www.topgabacho.jp/FI/Gamma.htm (in Japanese)

https://bencinistory.altervista.org/002B%20fotocamere%2047/02D%20GAMMA%20parte%201.html (in Italian)