This is an Opema II, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Meopta in Přerov, Czechoslovakia starting in 1954. The Opema II featured a coupled rangefinder, cloth focal plane shutter with top 1/500 speed and an interchangeable 38mm thread mount for changing lenses. Although very similar to the 39mm thread mount used by Leica, the lenses were not compatible and although the body bears a vague resemblance to the German Leica, should not be considered a Leica copy. This model, along with the scale focus only Opema I were the best 35mm cameras made in Czechoslovakia by Meopta at the time, but despite a clean appearance and good build quality, did not sell well inside or outside of Europe and is very hard to find today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), forty 24×32 exposures on a 36-exposure roll

Lens: 45mm f/2.8 Meopta Belar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: 38mm Thread Mount, 28.8mm Flange Distance

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: None

Weight: 630 grams, 478 grams (body only)

Manual: https://cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/meopta_opema.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Meopta Opema II is a well built and nicely designed Leica adjacent camera. It has a similar feature set, but is different enough that it cannot be called a copy. Limitations of the camera are its 38mm lens mount and 24mm x 32mm exposure size, otherwise I think this is a camera that could have sold far better than it did. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

Meopta was founded in 1933 as Optikotechna in Přerov, Czechoslovakia. The company made all kinds of optics related products such as condensers and lenses. Their lenses were used by other manufacturers for enlargers, binoculars, projectors, and cameras. As the company grew, they started making their own cameras, binoculars, rifle scopes, and slide projectors.

Meopta was founded in 1933 as Optikotechna in Přerov, Czechoslovakia. The company made all kinds of optics related products such as condensers and lenses. Their lenses were used by other manufacturers for enlargers, binoculars, projectors, and cameras. As the company grew, they started making their own cameras, binoculars, rifle scopes, and slide projectors.

By the mid 1930s, as tensions grew in Europe, Optikotechna became a major supplier of military optics for the Czech military. Once war broke out and Germany occupied the country, Optikotechna continued making military optics for the German war effort.

In 1938 (some sites say 1939), Optikotechna bought out a company called Bradac Brothers who made a couple of different Twin Lens Reflex models known as the Kamarad I and II, the Autoflex, and Optiflex. This line of cameras would be re-released as the Flexette in 1939, which would be the basis for future Flexaret models.

After the war, the company was nationalized and renamed to Meopta, which is short for Mechanická Optická Výroba, which means ‘mechanical optical manufacturing’ in English. Although Meopta continued production of optical equipment for the Czech military, they continued to expand as one of the world’s largest suppliers of cinema projectors in the 50s and 60s. By 1955, as a result of decreased need for military applications, Meopta strongly shifted their focus towards civilian products.

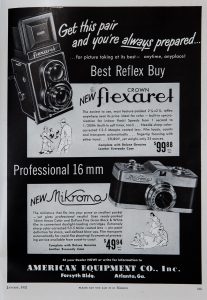

Although the company still exists today, Meopta’s greatest success as a camera maker happened in the 1950s when their successful lineup of Flexaret TLRs were being produced. The first models were sold in Europe only, but by the early 1950s, some models started to find their way out west. An American importer named American Equipment Co., Inc, based out of Atlanta, GA began importing Flexaret TLRs under the name “Crown Flexaret”. The appeal for Czech made TLRs came at a time when Germany TLRs like the Rolleiflex and Rolleicord were still very expensive.

In the January 1952 ad to the right for the Crown Flexaret, the camera was advertised with a retail price of $99.88. Compared to the 1952 Montgomery Wards camera catalog, both the Rolleiflex Automat K4A and Rolleicord III sold for $285 and $149.50 respectively, making the Flexaret a much more attractive option.

Even though Meopta was most successful as a maker of medium format TLRs, the company did also produce some 35mm models. The first was a strange device called the Optikotechna Spektaretta came in 1939, and it used a complex series of color-separation prisms and red, green, and blue filters which exposed three 24mm x 24mm images onto black and white 35mm film. For each exposure, three images were formed, and after developing, the three images could be merged back together to create a single color image.

Clearly a niche camera, the company’s next 35mm cameras wouldn’t come until the 1950s. A selection of simple scale focus cameras with names like Etareta, Etaretam and Axoma were created, along with an upscale interchangeable lens camera called the Opema.

In the era the Opema was released, the hottest selling 35mm rangefinders all came from Germany. The Leitz Leica and Zeiss-Ikon Contax were very high quality and expensive cameras with interchangeable lenses and focal plane shutters. Between the two, the Leica was the most common and a large number of companies from many other countries in Europe, the Soviet Union, Japan, and the United States had released models with similar feature sets and similar designs.

The designers at Meopta realized that their camera would never match the Leica rangefinders success, but they didn’t need to. If they could successfully build an affordable “Leica adjacent” model with similar features, but could be sold at a more affordable price like their Flexaret TLRs, they probably thought they’d have a popular model on their hands.

Two versions of the Opema would be released, both in 1954, one with a rangefinder and one without. The Opema I was a scale focus camera, and the Opema II had a rangefinder. While sharing a similarly shaped body as a Leica II, the two cameras had more differences than things in common. One of the most significant is that the Opemas did not expose 24mm x 36mm images like both the Leica and Contax, rather, smaller 24mm x 32mm images. This size was also used by a variety of Japanese camera makers as 24×32 images not only allow you to fit more exposures on a roll of film, but that size has a more appealing 3×4 aspect ratio and were easier to enlarge to 8×10 prints.

Other differences between the Opema and Leica is that the although both cameras use an interchangeable threaded lens mount, the one on the Opema was 38mm vs 39mm on the Leica, making the lenses incompatible. Another big difference was that the film back took a cue from the Zeiss-Ikon Contax in which the entire back and bottom come off in one piece, making the camera easier to load. The arrangement and style of the rangefinder was different too, more in line with Leica’s then new M3 in which both the rangefinder and viewfinder windows were combined.

The use of a 38mm lens mount proved to be a strange choice for Meopta as it meant that the huge numbers of already available Leica lenses could not be used. This likely proved a challenge towards more widespread adoption, but also considering the Leica Thread Mount patents had been nullified after the war, there’s really no reason why Opema couldn’t have used it.

Meopta would build a total of eight lenses in the Opema’s 38mm mount with a ninth lens, a Carl Zeiss 60mm f/1.5 Sonnar made with a special Opema adapter that could be special ordered. Of the eight Meopta lenses, five were rangefinder coupled, and two, a 30mm f/6.8 Largor and 180mm f/6 Telex were not coupled. A special reflex housing was also made for a 210mm f/4.5 Belar lens was also made. In addition to lenses, additional accessories such as a microscope adapter, copying stand, and other specific use devices were produced.

Unlike the company’s more successful Flexaret TLRs, the Opema was not exported to the United States, so I was unable to find any prices in US dollars, but in a catalog page shown to the right, with the 45mm f/2.8 Belar lenses, the Opema I and IIs had a retail price of 660 and 790 Czech Korunas. This represents an approximate 20% premium for the rangefinder model.

In my research for this review, I found no information regarding production numbers of either Opema camera, but the models relative obscurity and limited sales in Czechoslovakia suggests that not a lot were made. I also do not know the exact years the camera was made. One estimate suggests the cameras were produced from 1954 to 1959. While I think the 1954 estimate seems likely, I doubt the cameras were still in production 5 years later.

No further updates to the Opema or a follow-up Opema III were ever released. If a third model ever were to be released, I have to believe that a change to the 39mm Leica Thread Mount and possibly the inclusion of slow speeds would have been likely considerations.

Meopta would never again produce a premium 35mm camera, instead staying put on inexpensive scale focus cameras and their Flexaret TLRs. The Flexarets would see continued success through the 1960s and end production with the Flexaret VII around 1971. Meopta would continue to exist, producing other types of products such as military and civilian use rifle scopes, binoculars, and other optical goods. The company still exists today with their current day website focusing on Industrial, Sport, and Military use products.

Today, there is a large interest in Leica copies and Leica equivalents. While I believe this camera falls into the latter category, there is demand for models like these. Czech cameras often fly under the radar of some collectors, but those who have been around long enough know them to be well made and capable devices. The build quality and ergonomics of this camera are very good, so it is well deserving of both a place on your shelf, and as long as you don’t mind images that are 4mm narrower than a typical 35mm camera, can be a lot of fun to shoot.

My Thoughts

The term “GAS” is affectionately known among camera collectors as “Gear Acquisition Syndrome”, its that contagious desire passed along from one collector to another to add something to the collection that you probably don’t need. GAS is most commonly applied to cameras, but can be anything photography related from lenses, light meters, motor drives, bags, or pretty much everything else. I am well aware that in the years I have been writing on this site and recording the Camerosity Podcast, I have evoked GAS in a huge number of other people. I review something and then someone says they must go out and get one of their own. But sometimes the opposite happens.

As I am exposed to more and more people, often a camera gets brought up which is not currently on my shelf, and while the number of things missing from my collection is smaller than it used to be, I am not immune to the cruel grip of GAS.

Such an occasion happened on Episode 65: The One with all the Europeans where the topic of Czech cameras came up. A participant showed off his Meopta Opema II and I was doomed. I had to have one. Of course, sourcing an uncommon Czech camera in the United States which is both in good condition and affordable proved to be a challenge, but I employed one of the most successful cures for GAS…patience.

As I waited, the days turned into weeks, and weeks turned into months, until one day, a very nice and supposedly working Meopta Opema II showed up on everyone’s favorite online auction site for a reasonable price. I won the auction and patiently awaited for its arrival from Germany.

When I first handled the Opema II, I was impressed with its build quality. The camera had a very dense and compact feel to it, not unlike quality 35mm rangefinders from Germany and Japan. The chrome had a deep finish that showed little wear and no oxidation and the body covering was in tact with no tears or cracks. A Leica copy this camera is not, but it is pretty clear that whoever was responsible for the design of this camera took inspiration from it. I refer to cameras like these as “Leica adjacent” cameras.

The top plate controls are laid out slightly differently than the Leica, but are in the same general order as to still be familiar. A low profile rewind knob starts things off on the left, but strangely does not pop up, which makes rewinding film a bit of a challenge. Next is a nicely engraved Meopta logo with the words “Made in Czechoslovakia” engraved next to an ordinary accessory shoe.

On the lower step is the shutter speed dial with engraved speeds from 25 – 500 plus Bulb. The shutter speed dial rotates as the shutter is cocked and fired, so you must wind the shutter first before changing speeds or else the index mark won’t line up correctly. Also care should be taken not to let any part of your hand touch the dial as you press the shutter release as it will slow down the operation of the shutter. Next is the cable threaded shutter release button, surrounded by a film transport collar. Rotate the collar in the direction of the arrow to rewind your film, and towards a red dot for normal transport. Finally, is the film combination film advance knob surrounded by the exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made and must be manually reset after loading in a new cassette.

Around back, apart from the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, there is nothing else to see other than a large swath of body covering on the rear door.

Flip the camera over and we see one of the biggest differences from a Leica, which are the Contax style dual film door locks. This style of lock must be flipped up and rotated 180 degrees to unlock the back of the camera which completely slides off. An additional purpose of these locks is to open and close reloadable metal cassettes that would have allowed for cassette to cassette transport. In the center is a 3/8″ tripod socket which was the standard size of many European cameras of the 1950s. This is larger than the 1/4″ size that we use today, so if you’d like to mount this camera to a modern tripod, an adapter would be required.

The sides of the camera are symmetrical as the removable back negates any need for a hinge or door latch. The Opema II has metal strap lugs on both sides of the camera meaning that attaching a strap can be done without relying on the original leather case.

With the back off, we see the Opema’s rather ordinary looking film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a removable metal take up spool or a compatible reloadable metal cassette. The design of the spool looks nearly identical to those used by the Ihagee Exakta. I checked with an Exakta I had here and found that the two spools could be interchanged without issue, so if you ever find yourself in possession of a Meopta Opema with a missing take up spool, one from an Exakta should work.

Two unpainted rails above and below the film gate should reduce friction as film passes along it, however the pressure plate on the inside of the door is flat black metal without any resistance saving features. No foam or fabric based light seals are found anywhere in or around the film compartment. The camera’s serial number is engraved directly below the film gate.

One of the more familiar parts of the Opema is when looking at the collapsible 45mm f/2.8 Belar lens. Resembling a Leitz Elmar, all of the lenses controls are all where you expect them to be. An engraved depth of field scale is nearest the camera body, with the focus scale in front of it. Distances from 1 meter to infinity are engraved and can be moved by turning a small round tipped handle on the lens focus ring. Like the Elmar, the lens must be extended before shooting the camera, although there is no protection to prevent accidental exposures with it collapsed. With the lens extended, a short clockwise twist will lock it into position to prevent it from collapsing while shooting. Up front, on the face of the lens is the aperture ring with engraved marks from f/2.8 to f/22.

If the collapsible Belar lens is a familiar part of the Opema, you might think its threaded screw mount would also be, but you’d be wrong. At a quick glance, this looks like any normal interchangeable lens rangefinder with the Leica Thread Mount, the one here is 1mm smaller, at 38mm wide. In the 1930s and early 40s, companies like Canon, Clarus, and Perfex made interchangeable lens rangefinder with 38mm lens mounts to avoid a patent infringement that Leitz owned on the 39mm Leica Thread Mount, but as all prewar German patents were nullified after the war, any company was free to use the mount on their camera, and it is strange that Meopta didn’t. In my research for this article, I found no explanation why they went this route, but if I had to make a while guess, it could be that Czechoslovakia’s close ties with Germany during the war, might have suggested there was still some misguided prewar loyalty. Whatever the reason, the Opema’s 38mm lens mount is not compatible with any Leica lenses, or lenses made for any other rangefinder. Nevertheless, removing and attaching the lenses works the same way, righty tighty, lefty loosey.

The Opema has a combined image coupled rangefinder which relies on a beamsplitter to combine light entering both windows on the front of the camera into a single image. While the preferred method of rangefinder design for most companies in the 1950s, it does have the side effect of being a bit darker than earlier rangefinders where the viewfinder and rangefinder are separate. The Opema shoots slightly more square 24mm x 32mm images, and the shape of the viewfinder reflects that, giving it a slightly more narrow view than most other cameras. The circular rangefinder patch in the middle is tinted yellow with the rest of the viewfinder having a blue tint. Despite the slightly dark view, I found the contrast between the two images to be pretty good. I was fortunate as this example did not suffer from any haze in the viewfinder which is common from mid century rangefinders. As you’d expect from a camera of this vintage, no exposure information is visible, nor is there any attempt at parallax correction. Overall, the viewfinder was good, but unremarkable.

The Meopta Opema II has a lot going for it with only one major con, which if you’ve read the section above, you should be able to guess what it is. The design and cosmetics of the camera is quite nice. The chrome and body covering are as good as any Leica adjacent camera out there, the ergonomics are good with controls in all the places you’d expect them to be. The viewfinder, while a bit dark is on par with other 1950s rangefinders, and the lens, although not made by an A-list German lens makers like Zeiss or Schneider, should be capable of pretty good images. The one con? That the Opema uses its own diameter lens mount and cannot accept the millions of LTM lenses out there severely hampered the success of this camera, which is a shame because everything else is pretty good. While it is unlikely a small company from Czechoslovakia would have significantly disrupted the German or Japanese camera industries, there was the potential for this to be an economical third option.

Pros and cons aside, what is the camera actually like to use and what kinds of images are it capable of? Keep reading…

My Results

When the Meopta Opema II arrived, I felt as though everything was in working condition, but wasn’t 100% sure, so whatever I chose for my first roll, it couldn’t be something valuable like my precious Kodak Pan-X which is my favorite film ever. My go to film of choice for first rolls is usually Kodak TMax 100, not because it’s not a worthwhile film, but that I still have several unopened 100′ bulk rolls of it, so I can afford to be generous with its use.

For the Opema however, I decided to try something different. I’ve had a bulk roll of something called Kodak 2484, a black and white panchromatic film that had expired in the 1980s. Looking up the film online, it is not exactly rare, but information about what it was originally designed for. I’ve heard everything from it was designed for testing missiles to taking photographs of Cathode Ray Tubes like on an oscilloscope. Whatever its intended use, Kodak 2484 was originally a very fast black and white film, with strong grain, and whose speed is also up for debate. A commonly cited speed for it is ASA 2000, but that it doesn’t age well, so you need to slow it down for modern use. I figured, “what the hell” and cut off what I approximated would be the length of a 24 exposure roll, loaded it into an empty cassette and decided to shoot it as if it was an ASA 200 speed film.

Before getting into the camera, a few comments about the film. I was quite surprised that my random guess of ASA 200 on a camera whose shutter was of questionable accuracy proved to be pretty close for most of the scenes I shot it in. Grain was definitely strong, but no worse than any ASA 800 or faster film I’ve shot. As is often the case with heavily expired film, some bromide drag where shadows line up with where the sprocket holes in the film were. The images do not have strong contrast, which I tend to like, but often erred on the side of muddy blacks than blown out whites. I feel as though one extra stop would have done the film better justice. I’ll have to make a note for the next time I shoot this film to treat it like an ASA 100 speed film.

Although most of the roll turned out okay, it did become apparent that the shutter on the camera was barely working and the camera was increasingly developing film transport problems, the more I went through the roll. Advancing the film to make 32mm wide images only requires 7 sprockets instead of 8 and for some reason, it resulted in some super tight frame spacing, that throughout the roll started to overlap more and more. The beginning of the roll had no overlap, but as I got further into it, it got worse. I doubt this is normal, but I guess its plausible that in order to change the frame spacing, this was an unintended consequence.

As for the rest of the images, I noticed that several of them showed shutter capping where the right side of the exposure was significantly darker than then left, as a result of the two curtains not separating correctly. This is a tell tale sign of any focal plane shutter being out of adjustment.

Of the images that turned out good, they were…ok. The heavy grain of the Kodak 2484 made determining sharpness a challenge, but I generally thought the images showed acceptable sharpness across the frame for a Leica adjacent camera by a small company. Many of my images were shot outdoors and I noticed no vignetting near the corners, suggesting the Belar lens has good coverage. My best guess would be with a perfectly working example on small grain film, sharpness would be on par with maybe a Zeiss Tessar or similar lens. The strong blue coating of the front lens element suggests that color accuracy might have been good, but I never shot any color film on this camera. Not wanting to risk further degradation of the shutter or the film transport, after seeing the images from this test roll, I decided not to shoot a second roll as I felt as though I already had enough information to draw a fair conclusion of the camera.

I was quite impressed with the Opema II, but having previously shot a Meopta Flexaret VII and having owned a few other Flexarets, I guess I probably shouldn’t have been so surprised as the Flexarets are very capable TLRs. I keep using the term “Leica adjacent” in comparing the Opema II to a Leica, but I would say the term “Rolleiflex adjacent” would apply to the Flexarets as well. There are enough differences to where you can’t really call them copies, but there’s also enough that’s alike to where you can clearly tell who their inspiration was.

The overall appearance and tactile feel was a step up from most Soviet rangefinders I’ve handled, and maybe on par with most Japanese rangefinders. Ergonomics were good, and although the viewfinder was a tad cramped, I appreciated the large circular rangefinder patch and good contrast. The lack of slow speeds probably limited some photographers, but I didn’t mind only having a choice of 25 through 500 as those are the ones I most often use anyway.

By far though, the two most limiting aspects of the camera were its non standard 24mm x 32mm image size would have turned off Kodak based photofinishers, plus those who mount slide into common size slide mounts, but mostly, the choice to not use the Leica Thread Mount. While there is some bravada with going your own way and coming up with something different than what the Germans (and pretty much everyone else) were doing, it ultimately was the downfall of this camera. That in order to buy into the Opema system meant you had to buy all new lenses would have made this a tough sell to anyone outside of its home country.

Which is a shame too, as there’s far more to like about the Meopta Opema II than not. I’m not holding the camera’s functionality against it, as this is a 70 year old camera that likely hasn’t seen a technicians desk in probably half that time. Even the best cameras need work after almost three quarters of a century. When the Opema worked, it did a great job, was easy to use, and delivered decent images. For that, I am happy to give this camera a place on my shelf and I am certain you would too.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Opema

http://www.novacon.com.br/odditycameras/Opema.htm

https://cameracollector.net/meopta-opema/

https://web.archive.org/web/20161102044409/http://homepage3.nifty.com/KAR120C/opema01.htm (Archived, in Japanese)

Interesting camera – I have some Meopta enlargers for 35mm and 6×6, and they’re both solidly built and reliable things. I’ve always secretly wanted a Flexaret to go with them, but I had no idea this was a thing. I’ll have to keep an eye out for one.

Minor correction to your review, though: you say that “looking at the inside of the locks, unlike the Contax however, I do not see the two nubs that would be used to open and close a metal reloadable film cassette, suggesting that cassette to cassette transport on this camera is not possible”. Meanwhile, the photo of the inside of the back very clearly shows the locks have nubs that would interact with “labyrinthine” cassettes! The fact the take up spool is removable, the fork it sits on matches the fork on the film cassette side, and the rewind knob is flat and doesn’t pop up suggests to me that this was very much intended to be operated cassette-to-cassette like a Contax II. In fact, rewinding one of those is borderline torturous, so cassette-to-cassette operation is the best way to use one.

I should also note that the Contax/Kiev design is also prone to similar frame spacing issues, and if I remember right, it’s usually due to the tension/friction being uneven at one end of the film transport compared to the other (i.e. the grease on the rewind fork being too thick), or something along those lines (it’s been at least 12 years since I fixed this problem on a Kiev). I suspect that based on the Contax influences on the Opema, this is probably due to a similar issue, and should be a relatively easy fix.

You’re right in regards to the reloadable cassettes. I am not sure what I was seeing while I was typing that section of the review. I have edited it to be more accurate, thanks for pointing it out. Also, I agree with your assessment of the film spacing issues. Clearly, this camera is in need of a CLA, but that’s not something that’s in the budget for me right now.

I’m curious to know if there was any cross-compatibility between the Opema and the film cassettes for other 35mm cameras, or even if they ever released any Opema-branded cassettes; I find it hard to believe they’d be making their own for just two cameras in the mid 1950s.

The keying on the underside (inside?) of the locks on the back don’t match the orientation (or even design/spacing) of the Contax and Kiev ones. It looks closer to the Leitz design, but without the small “pin” that pushes the flat spring out of the way. Very odd.

FWIW, our old Slovakian friend Gejza Dunay (“cupog” on The Bay) specializes in Czech vintage cameras. He soes not speak kindly about Meopta product, especially the Flexaret TLRs, stating that they have reliability issues and tequire quirky repairs to keep them working.