This is an Olympus Ace, a 35mm interchangeable lens rangefinder camera produced by Olympus Optical Co., Ltd starting in 1958. The Ace was the first and only rangefinder camera produced by Olympus with interchangeable lenses and had features like an automatic exposure counter, rapid wind lever, projected frame lines, and automatic parallax correction. Only four lenses ranging from 35mm to 80mm were made using its own unique bayonet lens mount. The Ace was quickly replaced a year after its release by the Ace-E, which included an uncoupled selenium exposure meter. A variation of the Olympus Ace-E was sold by Sears as the Tower 19. The Ace lineup did not sell well and ended production in 1961.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lenses: 4.5cm f/2.8 Olympus E.Zuiko coated 5-elements in 4-groups and 3.5cm f/2.8 E.Zuiko coated 5-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Olympus Ace Bayonet

Focus: 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: No. 00 Copal SV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 640 grams (w/ 4.5cm lens), 616 grams (w/ 3.5cm lens), 522 grams (body only)

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/olympus_pdf/olympus_ace-e.pdf

The era of Olympus as a maker of interchangeable lens rangefinder cameras predates most Japanese companies like Nikon, Minolta, Konica, and Nicca. If that statement has you scratching your heads because you don’t remember such an early interchangeable lens rangefinder camera made by Olympus, you’re not alone.

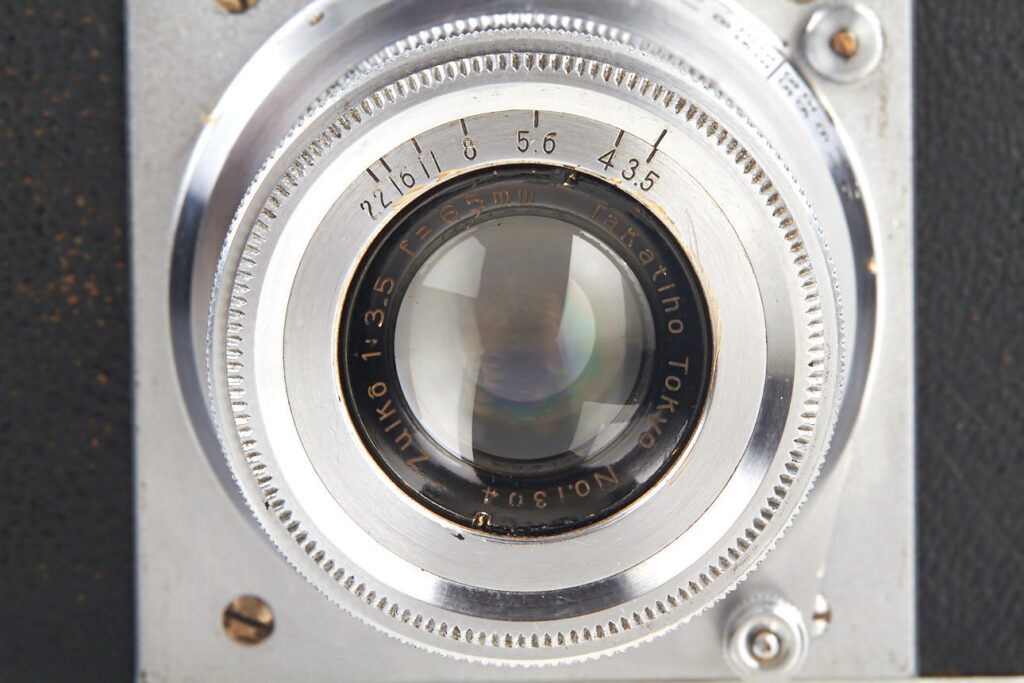

For the first Olympus camera with interchangeable lenses, we have to go back to 1937 when an ambitious rangefinder camera called the Olympus Standard made its debut in a large number of Japanese trade magazines such as Asahi Camera. The Olympus Standard was made while the company was called K.K. Takachiho Seisakusho who had previously used the Olympus brand name on a camera called the Semi Olympus, released in September 1936. The Semi Olympus was a fairly ordinary folding camera that shot 4.5cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film.

The company’s second camera was announced less than a year later, in June 1937 and in several more issues throughout the year. Despite sharing the Olympus name, the new camera would share almost nothing with the Semi including the type of film it used. Instead of 120 film, the Olympus Standard used 127 “Vest Pocket” film and would make 4cm x 5cm images. Although double perforated 35mm film was widely in use in Europe and North America, the film was difficult to find in Japan and very few cameras were made to use 35mm film.

The Olympus Standard was an ambitious solid bodied camera that had a coupled rangefinder and an interchangeable lens mount. According to advertisements at the time, five lenses were being developed with focal lengths of 5cm, 6.5cm, and 13.5cm. The standard lens included with the camera was a 6.5cm f/3.5 lens, but an f/2.7 version is thought to exist. A “large aperture” 6.5cm f/2 lens was reportedly in works as well. Due to the larger 4cm x 5cm image size compared to regular 35mm film, the 6.5cm lens was the standard focal length, the 5cm would have been a wide angle lens and the 13.5cm a telephoto.

Between June and December 1937, ads for the Olympus Standard appeared in each month’s issue, each time revealing something different (the November and December ads were the same). In the August 1937 ad, the price was revealed to be ¥275 for a version with the 6.5cm f/3.5 lens which would have priced it at exactly the same as the Hansa Canon 35mm rangefinder. In all of the advertisements, images of the camera can be seen, but in two, serial numbers 101 and 107 can be seen on two different cameras, suggesting that up to 10 prototypes might have been completed.

After the December 1937 issue, all references to the Olympus Standard disappeared and the camera was never mentioned again. Reasons for the cameras disappearance are not completely clear, however in a later interview with the camera’s designer, Sakurai Eiichi, he said that the reason was the company lacked the resources to produce such a complicated camera in large numbers. Other possible reasons were that the film flatness was a problem with 127 film of the day, and subtle variations caused images to appear soft in test examples. Another theory that has been thrown around is that in 1937, Japan was engaged in the Second Sino-Japanese War with China, and that Takachiho had a contract to produce optical goods for the Japanese Navy and that they needed to redirect their resources for military production. Considering Japan’s war with China coincided with World War II, by the time Japan was no longer engaged in war with anyone in 1945, the priorities of the entire industry changed significantly enough, that a camera like the Olympus Standard was no longer needed.

Takachiho would adopt the name Olympus Kōgaku Kōgyō K.K. in January 1949 and their postwar production largely consisted of the 6cm x 6cm folding Olympus Six, and the later Olympus 35 camera. While both the Olympus Six and Olympus 35 were certainly good cameras, they were hardly the ambitious models that the Olympus Standard promised.

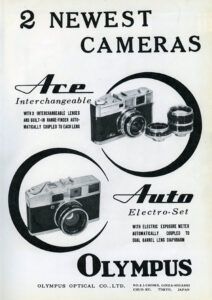

Olympus would stick to largely simple cameras throughout most of the 1950s, with their top of the line models being their Olympus Flex TLR and their Olympus 35 S rangefinder cameras. The idea of another interchangeable lens Olympus camera didn’t come until almost 2 decades with the December 1958 release of a compact 35mm rangefinder called the Olympus Ace.

The Olympus Ace was an innovative camera, which at the time was one of only two Japanese rangefinder cameras with both interchangeable lenses and a leaf shutter. For most of the world, interchangeable lenses required a focal plane shutter as the shutter needed to be entirely behind the lens. With most fixed lens cameras with leaf shutters, the shutter was in between lens elements, and if you wanted to change the lens, you could only change some of the elements, so it took some advancement of shutter design to come up with a way to have the entire lens in front of the shutter blades.

The only other Japanese camera to accomplish this feat before the Ace was the Aires 35-V which used a large medium format shutter to have enough clearance for the lenses, but with Olympus’s Ace, the camera was designed in a way where the entire lens assembly would fit in front of the Copal SV Leaf shutter, with the only sacrifice being that nothing faster than f/2.8 would ever work. This was hardly a consolation though as Olympus saw the Ace as an affordable alternative to more expensive German and Japanese focal plane shutter interchangeable lens cameras.

There is very little information online about the development of the Olympus Ace, or who it was designed by. I am not even certain the camera was ever sold outside of Japan as there is almost no English language marketing material for it. Only the following article and one advertisement (see below) from the May/June 1959 issue of Camerart magazine has anything in English written. Camerart was an entirely Japanese publication, written entirely in English, so this may very well be the only contemporary information about it ever written in English.

According to the article above, the camera was said to be available in the US and Canada for $79.95 with the 4.5cm f/2.8 lens and both the 3.5cm wide angle and 8cm telephoto would be an additional $49.95 each. This is the only evidence I have ever been able to find about the camera being sold outside of Japan however, so either a very small number ever made it to North America, or this article was printed before the decision was made to not sell it here.

In Japan, the camera was sold with any combination of the three lenses, or in a kit with all three together. The prices according to a 1959 ad from Asahi camera were as follows.

- ¥17,800 – With 4.5cm f/2.8 lens

- ¥18,800 – With 3.5cm f/2.8 lens

- ¥19,800 – With 8cm f/5.6 lens

- ¥32,400 – With all 3 Lenses

It is not clear whether or not the Olympus Ace was exported to North America, but if it was, it couldn’t have been for long as the camera was only made for about 12 months. In December 1959, an updated model called the Olympus Ace-E was released, featuring a slightly different body and an uncoupled selenium meter. With the release of the Ace-E, the 8cm f/5.6 lens was replaced with a slightly faster 8cm f/4 model, bringing the total number of Ace mount lenses to four.

During production of the Ace-E, an agreement with the American department store chain, Sears, Roebuck & Company was reached where Sears would sell a version of the Ace-E as the Sears Tower 19. Other than name, the Tower 19 was identical to the Ace-E. In the 1960 Sears Camera Catalog, the Tower 19 appeared with the 4.5cm f/2.8 lens for $79.95 with both the 3.5cm and 8cm lenses selling for $39.95 each. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $860 and $430 today. Both cameras were sold until April 1961 at which point production of the Ace series ended.

My first experience with an Olympus Ace was actually with the Sears Tower 19 variant. The Tower 19 came to me in physically nice but completely inoperable condition. The lens was wobbly and looked as if it had been partially disassembled and not put back together correctly. I tried what little I could to get it running, but it was beyond repair so it sat on a shelf for years until one day I saw a lot of four Olympus Ace cameras on eBay for a very reasonable price. I put in my bid and won the auction for a per camera cost of about $25. The seller did not claim any were working, but I figured that out of four, at least one had to work, right?

To my surprise, all four worked, at least somewhat. Of the two best ones, one had the standard 4.5cm f/2.8 lens, but the other had the much less common 3.5cm f/2.8 wide angle lens. I didn’t need four Olympus Aces, but I needed at least two bodies to display the lenses, so two stayed with me and the others went into the “to trade/sell” pile.

Although I had already handled the Tower 19, its condition left a sour taste in my mouth, so I never really paid much attention to it. Now with two good working Aces I had a better opportunity to appreciate the camera’s build quality, to which I was impressed. While I won’t go as far as to compare it to a Leica M3, some of the styling cues, especially the bezels around the viewfinder and rangefinder windows definitely gave off some Leitz vibes. The Olympus Ace is remarkably compact. Where most interchangeable lens rangefinders were growing in size, the Ace has compact dimensions. The Olympus Ace would have been designed in the era before Maitani released the first Olympus Pen, but it is clear that Olympus had some internal design language in which compactness was a treasured virtue.

The camera’s ergonomics are classic Japanese rangefinder. Everything from the design and location of the rewind knob, film advance lever, shutter release, and exposure controls around the perimeter of the lens are exactly where you’d expect them to be. The forward location of the cable threaded shutter release is comfortably located for your right index finger.

There’s little to see on the bottom, sides, or back of the camera, other than normal things like a 1/4″ tripod socket and a rewind release button on the bottom, forward angled strap lugs and door latch on the side, and the rectangular opening for the viewfinder on the rear.

Loading film is refined, yet uneventful from the solid metal sprocket shaft and brightly polished dual film rails. The camera has a couple subtle, yet convenient features such as a black dot on the rewind release button which rotates to indicate forward and backwards film transport and an automatic resetting exposure counter, something that wasn’t entirely standard when this camera was first released.

The viewfinder is of average size, but is very bright with extremely good contrast, showing a large rectangular rangefinder patch and three sets of frame lines with automatic parallax correction, one each for the 35mm, 45mm, and 80mm lenses made for it. Strangely, in the image to the left, I struggled to capture all three sets of frame lines in the image, but they are all there. While nothing about the viewfinder is innovative, it is clear Olympus put some effort into the design of the viewfinder and didn’t skimp on features like a lesser camera maker might have.

If there’s one area where the Olympus Ace falls short, it is in the design of the lens mount. A proprietary bayonet mount which was unique to this series of cameras, the release latch is extremely small and difficult to use. Between the four Olympus Aces I had, two of them were of moderate tightness, one was quite a bit tighter, but still usable, and the fourth was so tight, I needed to use the edge of a screwdriver to get the release to work. Even on the cameras where the lenses were easy to get off, they are all a bit difficult to get back on. Lining up the dots to attach a lens didn’t always guarantee a smooth experience as I found I needed to jiggle the lens while mounting it. While certainly each of these variations can be attributed to age, that it was like this at all suggests a less than perfect design.

Beyond the lens mount though, the Olympus Ace is a wonderful camera. My favorite features were its compact design with nearly perfect ergonomics. While out shooting, I never once needed to refer back to the user manual as the camera’s controls were intuitive and easy to use. The viewfinder was excellent and I had no problems finding focus in everything from bright sunlight to heavy shade.

Satisfied that I had a camera and lens combination worthy of a roll of film, I loaded up some bulk Jessop Pan 100S, a film that I had recently picked up on eBay for a good price. Jessops is a chain of photographic stores in the UK whose history dates back more than 90 years and for a while would sell their own house brand film which was made by a variety of different companies. Who exactly made this film was initially uncertain to me, however after doing some research online and consulting with my friend and film guru Alex Luyckx, he identified this as Ilford PAN 100 which made me happy as this was an emulsion I had never shot before.

Does it really surprise you to see a whole roll of sharp and great looking black and white images shot with an Olympus camera with a Zuiko lens? It shouldn’t, as Olympus was well regarded as one of the top tier Japanese camera and lens makers of the 20th century. Even before Olympus was producing their own cameras, their lenses appeared on a great deal of other camera makers bodies, including Leicas, Canons, and Mamiyas.

Although I did have access to both the 4.5cm standard and 3.5cm wide angle lenses, the wide angle lens had a good deal of haze in it, so the entirety of my test roll was done with the 4.5cm lens.

As you can see, the entire roll of rebadged Ilford 100 film returned wonderfully sharp and contrasty images with nary an optical defect in sight. A small amount of vignetting appeared in the corners, not unlike what you’d see with a Zeiss Tessar. I often find that lenses of this style produce images which perfectly walk the line of having near modern sharpness, while still maintaining a vintage, film-like look. Although I did not shoot any color film in the camera, based on these images, I see no reason to think that I wouldn’t have been pleased with the colors shot on subsequent rolls of film. I was definitely bummed I didn’t have a good example of the 3.5cm lens as I tend to prefer slightly wider lenses, but the 4.5cm lens did a great job.

Using the Olympus Ace, I was pleased with the ergonomics. Although a small camera that is much more compact than typical Japanese rangefinders of its day, I never once felt cramped while using it. I have average sized adult male hands and never struggled to locate the shutter release, change exposure settings, or wind the film. I also appreciated the order of controls around the shutter and lens. Focus is up front, which is the one you’re going to change the most. Next is the aperture ring which is the exposure setting I change far more often than shutter speed, which is closest to the body. The viewfinder, although not huge, is good enough for me, and I did not have any issues seeing the entire frame or rangefinder patch while wearing prescription glasses.

By far, the biggest ergonomic snafu of the camera is the lens mount, which I found to be difficult to both remove and attach lenses. The extremely tiny little lever on the side of the lens which acts as the lens release is just hard to use. Strangely, it was much harder to release on the 3.5cm lens than the 4.5cm, suggesting there is some variance depending on which lens you use. Thankfully, without another option besides the 4.5cm lens, I’m not going to change lenses often, and I don’t believe that original owners of these cameras did either.

Overall, I really enjoyed the Olympus Ace and might even consider it my favorite Olympus rangefinder I’ve ever used. I have liked many of the company’s other cameras, like the wonderful Olympus 35 SP, but with the option to change lenses and the more compact body, the Olympus Ace is a winner. While reflecting on this camera for this review, I am saddened that the Ace series was not more successful. Apart from the lens mount, these are great cameras with little to complain about. In addition to being very capable, fun, and easy to use, they are also very attractive. Some have suggested that these look like a miniature Leica M3, something that I don’t agree with, but I will say that they belong in the same category of capable and attractive cameras, just like the M3.

These aren’t easy cameras to find today, especially in great cosmetic or fully operational condition, but if you are a fan of compact rangefinders, and like the idea of changing lenses, or just simply like Olympus and want something different, the Ace is definitely a camera I’d recommend!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Olympus_Ace

https://www.biofos.com/cornucop/ace.html

https://www.flickr.com/photos/olympusrf/albums/72157626157260477/

Thanks for bringing this unusual camera to our attention. It was one of several innovative Olympus designs from this period, and one that I’d never hear of. Andy

This sounds like a real “Ace” of a camera. Damn you Mike, now I want tone…..

I feel pretty confident, you’ll like them! Just make sure get one that is confirmed working as they’re not immune to issues.

I’ve owned an Ace and Ace-E for many years with all the lenses, including the much rarer 8cm/F4 which I paid $$$, 15 yrs ago. Only time I ever shot it was a few rolls in Key West on vacation, and it was a very easy camera to carry with extra lenses. I agree with your assessment of a nice compact camera with interchangeable lenses which are decent optics.

Bravo…