This is a No. 1A Automatic Ansco, a folding roll film camera made by the Ansco Company of Binghamton, New York starting in 1924. The Automatic Ansco was Ansco’s top of the line camera in the 1920s, featuring a faster f/6.3 Anastigmat lens, a 7 speed Universal Ilex shutter, and came in a Morocco leather covered aluminum body. By far, the most interesting feature of the camera was that it had a wind up motor drive, capable of shooting up to 1 exposure per second without having to manually advance the film. Using special 6A Automatic Ansco film, six 2 ½” x 4 ¼” exposures could be made on a single roll. If the user didn’t have the special Automatic Ansco film, regular 6A Ansco film could be used, although only five exposures could be made. As one of the first motor driven cameras, the Automatic Ansco was certainly a historically significant camera.

Film Type: 116 Roll Film (five or six 2 ½” x 4 ¼” exposures per roll)

Lens: 4 ⅞ inch (~124mm) f/6.3 Ansco Anastigmat uncoated 4-elements

Focus: 6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Rotating Waist Level Finder

Shutter: Universal Ilex Leaf Shutter

Speeds: T, 1 – 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 1160 grams

Manual: https://www.camarassinfronteras.com/ansco_automatic_1A/manual/manual_ansco_automatic_1A.pdf

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/agfa_ansco/ansco_no_1a.pdf

The early 20th century was a period of great change in the photographic community. With the invention of photographic film in the 1880s to the release of the first Kodak camera in 1888, a large number of easy to use and portable cameras were being produced by companies all around the world. In the United States, the two biggest camera makers were Ansco (formerly Anthony & Scovill), and Eastman Kodak. In addition, other camera makers like Blair, Seneca, and Century also produced a wide range of cameras.

For collectors today, these early 20th century box and folding cameras are interesting, but rarely collectible. With the exception of a few premium models, a large majority of folding and box cameras have slow lenses with single or limited speed shutters. In an era when 1/100 speed shutters and f/6.3 lenses were considered fast, it can be difficult to get excited about a fixed focus camera with a single shutter speed and f/7.7 doublet lens.

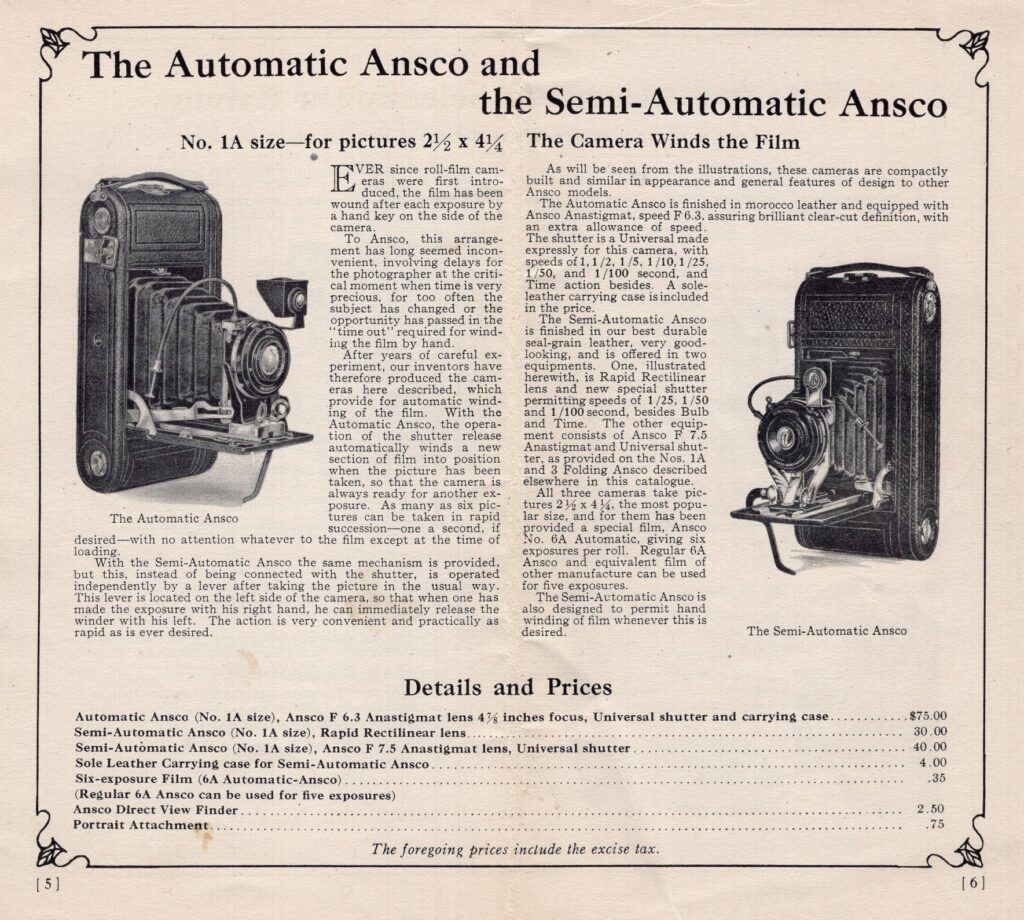

In 1924, Ansco released one such camera that was worthy of notice. The Automatic Ansco was an otherwise standard folding camera with a Moroccan leather covered aluminum body with the company’s premium f/6.3 lens and a 7 speed Universal Ilex shutter, but with one additional feature. The word “automatic” in the camera’s name refers to its spring wound motorized film transport which when wound up would automatically advance the camera to the next exposure allowing for exposures up to 1 per second to be made. An internal linkage was coupled to the shutter release upon which the film would advance, and automatically set the shutter for the next exposure.

Upon its release, the No. 1A Ansco Automatic was the only paper backed roll film camera with a motorized film transport, but it was not the camera with a spring wound film transport. That honor goes to a French camera called the Japy Le Pascal which was patented in 1899 and started production in 1900. The Pascal was a compact box camera which used a proprietary roll film with a paper leader and trailer that was wound onto a spring tensioned drum. Each roll of film made twelve 40mm x 55mm exposures and could expose the entire roll in as little as 3 to 4 seconds.

Unlike other Ansco folding cameras which came in different sizes, the Automatic Ansco only came in a single size, using the company’s No. 6A which was the same thing as Kodak type 116 roll film. In order to accommodate variances in the spring wind mechanism, frame spacing was a bit wider than most roll film cameras, so special film called No. 6A Automatic Ansco film was made for the camera which would allow for six exposures per roll. Optionally, the user could use regular No. 6A Ansco or Kodak 116 film, but when doing so, there would only be enough room for five exposures.

When it sold new, the Automatic Ansco sold for $75 with a roll of No.6A Automatic Ansco film costing 35 cents per roll. When adjusted for inflation, this compares to a little over $1400 and $6.50 for the camera and a roll of film respectively. In their 1926 catalog, the Ansco Automatic dropped in price to $60.

Shortly after the release of the Automatic Ansco, a more affordable camera called the Semi-Automatic Ansco was released which removed the coupling arm between the shutter and motor drive, requiring the shutter to be fired and the film to be advanced in two separate steps. Other changes with the lesser model were simpler shutters and lenses, plus the Moroccan covered body was changed to a lower quality seal-grain leather. This lesser featured camera sold for $40 with an f/7.5 Ansco Anastigmat lens, or $30 with a Rapid Rectilinear lens. Inflation adjusted prices for these were $930 and $700 today.

It is unclear how well the Ansco Automatics sold or for how long they were produced. I found entries for them in both Ansco’s 1924 and 1926 catalogs, but they were not in the company’s 1930 catalog. The most likely time when they were discontinued probably happened in 1928 when Ansco merged with Agfa and a large number of other Ansco branded models were discontinued. Considering how little information can be found, and how few show up for sale today, it is likely that these cameras were never built in large quantities.

Even if the Ansco Automatic wasn’t a big seller, the idea of a spring wound motor drive would be revisited many times in the years to come. In the 1930s, a German company called the Otto Berning & Co. produced a compact 35mm camera with a wind up motor drive called the Robot. The Robot would be immensely popular and remained in production for several decades. Other companies would soon follow with wind up models being released in the 1940s and 50s, by Bell & Howell, Kodak, Concava, and many others.

The Ansco Automatic came to me from a large collection of cameras, and I came very close to this review never happening as I initially dismissed it as yet another unremarkable early 20th century folding camera. The collection this came from had a huge number of folders, many of which were of little interest to me. The Ansco Automatic was stored in a large leather satchel which was an optional accessory for the camera, and had it not been for this satchel, I might have given the camera away in a lot of folders that I donated.

What caught my eye with this one was the quality of the leather satchel. It was a very thick and well made material which caused me to set it aside for further investigation, When I pulled the camera out, I didn’t even know what it was, but I could feel this was something a bit more special than everything else in the same box it came in. It wasn’t until I noticed the large wind up key on the side, above a nickel metal plate that said “Motor” which piqued my interest. A quick Google search for “Ansco Automatic No 1A” did I learn what this was.

The Ansco Automatic is quite large and heavy. Weighing in at 1160 grams (~2.6 lbs) it is one of the heaviest roll film folding cameras I’ve handled. The motorized part of the camera causes one side of the camera to be thicker than the other, giving the front door somewhat of an offset appearance. The outer body is made of aluminum, covered in a soft Moroccan leather, which on this example is still in excellent condition. Inside the camera is a wooden and metal core which adds to its heft but also means that the camera is very rigid and the appearance it is built to a high quality standard.

Looking at the two sides of the camera, one has a nickel metal plate with the word “Motor” on it with the wind up key. Winding the key is done by rotating it clockwise until it can no longer be turned. The manual cautions you not to over turn the key, so be careful when it starts to get tight. Above and below the motor key at each end of the camera are two pull out spool pins which when pulled out, make removing and inserting film spools easier. This side of the camera also has a 1/4″ tripod socket for mounting the camera in landscape orientation on a tripod.

The opposite side of the camera has a spool pin only near the bottom, and a manual film advance key near the top which is needed when loading in a new roll of film, but can also be used to manually advance the film if using the motor drive has failed, or isn’t desirable to use.

The back of the camera has two red windows, both for viewing exposure numbers on the paper backed film. One window is a standard circle near the upper right corner (with the camera oriented where the motor drive key is facing up) and the other is an elongated slot near the bottom with rounded edges. Which red window you use depends on whether you are using the proper No. 6A Automatic Ansco film, or non-automatic No. 6A Ansco or Kodak 116 film. With non-automatic film, the first exposure is made with the number 1 in the round window, but after that, no other exposure numbers will be seen in either window. With automatic film, the first exposure is made with the number 1 in both the round and elongated slot windows. When using automatic film, each exposure 2 through 6 will show the correct number somewhere in the elongated window, but not necessarily in the center. This is done due to tolerances in the spring mechanism as the thickness of the film causes the spacing to vary.

A spring loaded latch on the curved edge of the camera beneath the leather handle is used to open the film compartment. Slide the latch in the direction of the Motor drive key and pull up and the rear door will release. The entire rear door is removable, so be careful to not let it fall off the camera. Place the door in a safe location and lay the camera on a flat surface with the film compartment facing up.

Film transports from right to left (when the camera oriented with the Motor drive key facing up). As is the case with any roll film camera, an empty supply spool can be used as the take up spool. To move it, pull up on the spool pins on the side of the camera to allow the spools to be easily removed and installed. A fresh roll of film is loaded opposite of the take up spool. Extend the paper leader and attach it to the take up spool and using the manual film advance key, turn it until enough of the paper leader has securely attached to the spool. Reattach the back to the camera.

Opening the front of the camera is done by pressing in on a hidden button immediately below the motor wind key and folding the door until it locks into position. This camera does not have a self erecting design, so after folding the door completely open, you must extend the bellows by squeezing two round metal grips below the lens and pulling the lens and shutter as far as it will go. As with most early 20th century non self-erecting cameras, this process isn’t always smooth. Sometimes you need to jiggle the camera to get the bellows extended all the way.

When extending the bellows, a nickel plated metal arm should automatically swing out of the camera and fall into position to the side of the camera with the focus scale. This arm is the coupling between the shutter release and the motor drive and does not appear on the Semi-Automatic Ansco camera. Assuming the camera is in good condition, a small metal tab on the shutter release should slide into an opening near the tip of the metal arm, coupling the two together. If you struggle to open the camera, check this area of the camera and make sure the tab it in its correct position. Finally, the camera has a very long and strangely shaped kickstand that folds up behind the shutter. Ansco’s promotional material claims this was a better design than most folding cameras where the kickstand is embedded into the front of the door, because there’s no chance it could snag on something when the camera is folded shut. To use it, simply pull down on the kickstand until it is able to support the camera on a flat surface.

Once the camera is open, focusing is done by pressing down on a round button next to the focus scale and sliding it along the scale. The scale shows distances in both meters and feet and has seven “click stops” at various lengths from minimum to maximum focus. These click stops are a nice feature not often seen on many folding cameras as it holds the camera at a chosen distance, minimizing accidental changes in distance. It is interesting that maximum focus is not indicated as infinity, but rather 100 feet / 30 meters. I suppose Ansco was counting on depth of field to handle anything beyond that distance.

The Universal Ilex shutter is a self-cocking rim set design in which shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/100 are changed by a black ring around the shutter, similar to shutters like the Optimo made by Wollensak. An interesting fact is that both Wollensak and Universal were making rim set shutters before the German Compur, which only made dial set shutters until 1928. For long exposures, the Ilex shutter has a Timed setting, but not a Bulb setting. The lens diaphragm is changed via a tiny metal lever near the 9 o’clock position around the outside of the shutter. A scale near the top of the shutter has marks for f/stops from f/6.3 to f/45. This location is somewhat inconvenient as the larger apertures are difficult to read due to the location of the viewfinder, which is directly in front of it.

Speaking of the viewfinder, the Ansco Automatic features a swiveling reflex finder, similar to most other folding cameras of the era. In order to collapse and extend the bellows, the viewfinder must remain in a portrait orientation, however when landscape images are desired, it can be rotated 90 degrees so that the camera can be held on its side. A very clever feature of the viewfinder is a metal mask, which shows the correct rectangular aspect ratio which will be captured on film. When swiveling the viewfinder between portrait and landscape orientation, this mask also rotates 90 degrees to correctly retain the proper aspect ratio. I have never seen a folding camera with a feature like this.

Making exposures is my favorite thing to do on this camera as the sounds of the motor drive is very cool. When extending the bellows, a little metal tab on the shutter release linkage will slide into a slot on the motor drive linkage, coupling them together. A metal tab about halfway the length of this arm is where you press down to both fire the shutter and activate the motor drive. With a new roll of film loaded in the camera, the motor drive fully wound up, and the number ‘1’ appearing in one or both red windows on the back of the camera, set your focus, shutter speed, and f/stop and when you are ready to make your exposure, press down on the linkage arm as far as it will go. The shutter fires first, and then when the lever returns back to its original position, the motor drive will advance the film to the next exposure. If you are using the original No. 6A Automatic Ansco film, you’ll see each of the six exposure numbers in the elongated slot on the back of the camera. If you are using non-automatic No. 6A Ansco film, or Kodak 116 film, you will not continue to see exposure numbers, and you will only get five exposures on a roll of film due to the frame spacing.

Here is a short video I made showing the operation of the motorized film advance with a roll of 116 film loaded. Note that in the video I incorrectly refer to the Semi-Automatic Ansco as the Automatic Ansco Junior, but otherwise everything else I said is correct.

With a fully wound motor, you can fire the shutter at a rate of about one exposure per second, which for 1924 was lighting quick! As with all clockwork motors, as the tension on the spring nears its end, the motor drive slows down, so I don’t think that even when this camera was new, could you ever get six exposures in six seconds. When you’ve made your final exposure, activate the motor drive two more times to fully wind the backing paper onto the film spool to protect it from light.

When it is time to fold up the camera and put it away, you must make sure the viewfinder is in a portrait orientation, the kickstand is folded up and tucked in behind the shutter, and that the bellows are fully retracted with the shutter and lens entirely inside the body. As with extending the bellows, sometimes pushing them back in can be an erratic experience. If something feels like it is binding, do not use brute force, first check that everything is correctly where it belongs, and if so, jiggle the finger grips while trying to put firm, but consistent inward pressure until it is fully collapsed. The entire shutter and lens assembly should be behind the door hinge. Once everything is folded up properly, press inward on the two metal struts using both thumbs while pushing the door closed. You do not need to manually fold the metal motor drive linkage arm as it will automatically close as you fold the door.

Thinking back to when I first came across this camera, I am thankful that my original dismissal of the camera was later rectified as this most certainly is a camera worth playing with. Sadly, the leather bellows on the Ansco Automatic were completely shredded. In addition to every single seam having light pouring through, surface pieces of the leather were literally falling off every time I would open and close the camera. Although I do have a supply of 116 film I could have used in this camera to test it out, I do not have a good way of developing film this size, so combined with that challenge and that the bellows would have allowed more light through than the lens, I decided not to shoot it. Had I done so, my guess is the images would have looked pretty good. The f/6.3 Ansco Anastigmat lens was one of the company’s better lenses and would have compared favorably to some of the best medium format lenses of the era.

I love cameras like this, not just because of their pioneering features and thoughtful design, but also that time has mostly forgotten these kinds of cameras. While there is an incredible resource for early German cameras and simpler Kodak folders, I found very little about the Ansco Automatics. Based on their rarity, and probably a less than 4 year production run, I doubt many were sold, even fewer that have survived nearly 100 years, and sadly, of the ones that were, there is a good chance that at least some were discarded by people who like me, originally didn’t realize how special of a camera this is.

I’ll apologize to anyone out there reading this review who feels compelled to find an Automatic Asnco to add to their collection. In addition to there being very few available, using a search engine to find a camera called the “Automatic Ansco” is going to be a challenge as the majority of your results will almost certainly be for something else. If however, you are very lucky and can come across one and it is within your budget, you should definitely check it out. This is a camera worthy of inclusion in any collection!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-15380-Ansco_N%C2%B0%201A%20Automatic.html

https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/1a-automatic-ansco-built-motor-drive-1732869316

https://www.reddit.com/r/vintageads/comments/1ay4klw/ansco_automatic_no_1a_camera_brochure/