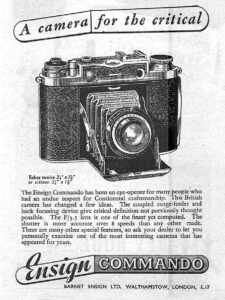

This is an Ensign Commando, a folding roll film camera made by Barnet Ensign Ltd. between the years 1945 and 1949. The Ensign Commando shoots both 6cm x 6cm and 4.5cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film and was originally made for the British military near the end of World War II. A small number of military use versions of this camera were made in 1945, but civilian versions were introduced in 1946, adding the dual format capability along with a couple cosmetic changes. The Ensign Commando is an advanced camera with features not commonly found on other Ensign cameras and was later replaced by the later Ensign Selfix series in 1950.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm or sixteen 4.5cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 75mm f/3.5 Ensar Anastigmat uncoated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ Sliding Mask for 4.5×6

Shutter: Epsilon Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold Shoe, No Flash Sync

Other Features: Moving Focal Plane Focus, Dual Aspect Ratios

Weight: 880 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Ensign Commando is a large and heavy folding camera built during World War II, originally intended for wartime use. With a rugged build quality and oversized controls, the Commando is an interesting camera with a high quality lens and features not found on any other British camera. Supporting a wide range of shutter speeds, two different aspect ratios, and a clever moving focal plane focus, the Ensign Commando is worthy of adding to any collection. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for wartime ‘street cred’ | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

Ensign was the name of a London based company that made a variety of cameras and photographic supplies in the 1800s and first half of the 20th century. I’ll try to keep this short as there is a very thorough history of the Ensign company on Adrian Richmond’s Ensign Camera site. Ensign went through many name changes, acquisitions, and mergers over the years which causes their complete history to be a bit confusing. Rather than repeat everything here, I’ll try to come up with just a short summary, but if you’re interested to know more, I strongly recommend reading Adrian’s site.

Ensign was the name of a London based company that made a variety of cameras and photographic supplies in the 1800s and first half of the 20th century. I’ll try to keep this short as there is a very thorough history of the Ensign company on Adrian Richmond’s Ensign Camera site. Ensign went through many name changes, acquisitions, and mergers over the years which causes their complete history to be a bit confusing. Rather than repeat everything here, I’ll try to come up with just a short summary, but if you’re interested to know more, I strongly recommend reading Adrian’s site.

Ensign got its start in 1836 when two men, George Houghton, and a Frenchman named Antoine Claudet opened a glass warehouse in London. The company was called Claudet and Houghton and they specialized in all forms of sheet glass and that for optical products. The company continually increased their product offerings over the next 3 decades, eventually becoming one of the largest glass suppliers in all of England.

In 1867, George Houghton’s son joined the company and Antoine Claudet died, which resulted in a name change to George Houghton & Son. The new company would continue to expand its product offerings beyond glass, expanding into new markets, including photographic supplies. In 1903, George Houghton & Son introduced its first photographic film, which they branded as Ensign Daylight Loading Film.

In 1867, George Houghton’s son joined the company and Antoine Claudet died, which resulted in a name change to George Houghton & Son. The new company would continue to expand its product offerings beyond glass, expanding into new markets, including photographic supplies. In 1903, George Houghton & Son introduced its first photographic film, which they branded as Ensign Daylight Loading Film.

In 1904, Houghtons would acquire 4 different camera companies, Holmes Bros, A.C. Jackson, Spratt Bros., and Joseph Levi & Co., and would become a Limited company known as Houghtons Ltd. The patents and expertise of these 4 companies allowed Houghtons Ltd to become a major supplier of optical glass, film, and cameras in the early part of the 20th century, employing over 1000 people at all of their locations combined.

In 1915, Houghtons Ltd would acquire W. Butcher and Sons Ltd. and would be known as the Houghton-Butcher Manufacturing Company furthering expanding their product offerings and manufacturing prowess. In 1930, Houghton-Butcher would rename itself to match the name of its products, and would become Ensign Ltd. During this time, Ensign Ltd had a variety of cameras, from simple box cameras, folding cameras, and a miniature camera called the Ensign Multex.

In the 1930s, Ensign would release a new folding camera called the Selfix. The new camera was similar to many other folding cameras made by American and German companies of the era, but one feature that would become a staple of the Selfix series was that they included masks to support two, sometimes three different aspect ratios. Manny of the 6×6 models would support 4.5×6 images, and 6×9 models would support 4.5×6 images.

Most Selfix models were basic, offering a flip up or optical viewfinder and Ensign’s own lenses, but some “Autorange” models were created with uncoupled rangefinders, and a small number even came with Carl Zeiss lenses.

In 1939, Ensign would release a new box camera called the Ensign Ful-Vue. The Ful-Vue was a simple camera with a large brilliant viewfinder on top with a large viewing lens that was said to be bigger and brighter than any offered by any other company up until this point. The Ful-Vue was very popular with amateur photographers, and was often purchased for children due to its simplicity. It is one of the company’s most recognizable cameras today and one that most collectors think of when mentioning the brand Ensign.

Looking at Ensign’s prewar offerings, most cameras were of the simple folding or box type. If you were a British photographer at the time looking for a top tier camera, you almost certainly got something made in Germany. In most countries, German companies like Zeiss-Ikon, Voigtländer, and Ernst Leitz were seen as the top of the line camera and lens makers, and for good reason, their cameras were quite good.

As war broke out throughout Europe, supply of these high quality German products came to a halt as most companies in and out of Germany concentrated on manufacturing for the war effort, and for what cameras were still made, they were not exported from one country to another. England saw this as a problem, with the unavailability of German cameras and optical products, they turned to their own manufacturers to meet the demand of high end cameras.

As war broke out throughout Europe, supply of these high quality German products came to a halt as most companies in and out of Germany concentrated on manufacturing for the war effort, and for what cameras were still made, they were not exported from one country to another. England saw this as a problem, with the unavailability of German cameras and optical products, they turned to their own manufacturers to meet the demand of high end cameras.

Early in the war, Ensign Ltd got to work on a high quality and portable medium format camera that could be used by the military and anyone who needed such a device. It is not clear exactly when work started or who was involved, but an unnamed folding camera would be revealed in 1945 for military use. Although unnamed, this new camera would eventually be known as the Ensign Commando.

The Commando was intended to be a high quality camera with an ambitious feature set. While not an exact copy of any German design, it borrowed some features from multiple German cameras and possibly even a Japanese camera. Featuring a combined image coupled rangefinder on the top of the camera, the Commando had oversized controls which allowed for easy use with gloves. Instead of changing focus by moving a helix or rotating one or many lens elements, the Commando had a movable focal plane which controlled the distance at which the lens focused. This design was very similar to the Mamiya Six, who patented a similar design in 1939. It is not clear whether or not Ensign borrowed this feature from Mamiya, or if the two companies just thought of the same idea together. Although requiring more moving parts within the body, the advantage to focusing with the film plane is that the linkages for the rangefinder do not have to travel through the fragile folding mechanism, plus in body focus also allowed for a focus knob to be located on the camera’s top plate, similar to some models made by Voigtländer.

Other features of the camera were a built in exposure counter which relied on gearing built into the film advance knob that could measure the distance the film was advanced to know when the next exposure had been reached, and also to automatically advance the exposure counter. This was a complicated feature found on very few cameras of the era, most notably the Zeiss-Ikon Super Ikonta series. Like the Super Ikonta, the automatic gearing was not precise enough to count off exactly 12 exposures per roll, so a limit was set to 11. On the plus side, the entire mechanism could be disabled and instead exposures counted by the numbers printed on film backing paper and read through a red window in the back of the camera.

By the time Ensign’s new camera was revealed, the war was nearly over and very few, if any were ever used in combat. Having a completed camera ready to go, and Germany’s manufacturing and economy in ruins, Ensign saw an opportunity to release the camera to the public to fill the void of German models. In addition, the release of a high quality British made camera could also help dispel prewar stereotypes that British cameras were inferior to those by German companies, and possibly even elevate the entire British optical industry to new levels of reverence.

In 1946, a slightly redesigned camera, now called the Ensign Commando was previewed to the public. Unlike the wartime camera which never featured the name “Ensign Commando” anywhere on the camera, the postwar, or consumer model, proudly had the cameras name embossed into the leather covering the body. Other changes include a redesigned film transport and the addition of support for 4.5cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film. The wartime “military” model only supported 6cm x 6cm images. A few other cosmetic changes were made, including a black leather piece on the front face of the camera.

Although shown in 1946 and widely advertised as being available, Ensign Commandos were in short supply and very few ever made it into dealer’s hands to be sold to the public. A combination of supply chain problems, plus difficulties in convincing the public that a British camera could be better than the German cameras everyone was used to, further decreased demand.

For two years, the Ensign Commando sold poorly, and in 1948, responding to criticisms of the camera’s difficult to load design and the shutter’s relatively slow top 1/200 speed, changes were made to the film transport and a new Epsilon shutter was revealed which increased the top speed to 1/300. In addition, the price of the camera was reduced to £43, although I do not know how much it previously sold for.

The changes did improve the camera’s perception among the photographic press as a few positive reviews for the camera were published in 1949, but it was too little too late, and the return of imported German exports and the demands for a simpler and less expensive camera resulted in Ensign pulling the plug on the camera in 1950, and replacing it with the similar, but also simpler Ensign Selfix 12-20.

Ensign, now called Barnet Ensign Ltd., would have marginally more success with the Selfix series which remained in production until 1961. A combination of good lenses and affordable prices appealed to the British press, something the Commando failed to do.

By the start of the 1960s, Barnet Ensign, along with other British camera makers found it difficult to remain competitive with the return of quality German cameras reintroduced back into the market. In addition to German competition, the rise of the Japanese camera industry brought in a large number of well built and inexpensive cameras, giving stiff competition to smaller companies like Barnet Ensign. A huge number of these smaller photographic firms would find it to be no longer economical to keep producing their own products, so many exited the camera making business.

Today, there is a loyal following of British camera collectors. Models like the Ensign Commando represent the best of what the country could make. Without access to German cameras immediately after the war, these models offered features and designs which were comparable to what was previously available. While the window of opportunity for British camera makers quickly closed, for the time it was open, a large number of interesting and capable cameras were produced which collectors seek out today. The Ensign Commando’s role as a wartime camera further adds to its appeal to both camera collectors and World War II aficionados, making this camera difficult to find, especially in the United States. If however, you have a chance to pick one up, this is definitely one which I would recommend checking out, regardless of where you live.

My Thoughts

I didn’t realize it before I ever handled one, but my collection of military spec cameras has increased with the addition of the Ensign Commando. A camera originally build to be used by the British military, the Commando is larger and heavier than many 6×6 folding cameras and has a large shutter release, film advance knob and top plate focus knob which can easily be used while wearing gloves. At a weight of 880 grams, the Commando is topped by only other other 6×6 folding camera in my collection, which is the Zeiss-Ikon Super Ikonta 530/16 at 920 grams. The Commando may be small enough to fold up and fit into a medium coat pocket, but you’ll never forget it is there.

On the upside, the Commando has a rugged and high quality build, that compares favorably to many other German cameras of the same era. With a dull chrome finish that shows no signs of oxidation or corrosion and a body covering that is entirely in tact, this particular example has aged well, no doubt a result of additional quality control during the manufacturing process.

While the Ensign Commando is a worthwhile camera to own, one thing working against it is that a huge number of folding cameras were made by companies all over the world shooting square or rectangular images on 120 and 620 roll film. Many of these cameras made by different companies in different countries all over the world share the same basic control layout, features, and image quality, so it can be difficult to get excited over the prospect of shooting yet another 6×6 folding camera. As I handled the Commando for the first time however, I got the sense that this camera might be special, so I was excited to get started on this review.

Up top, two knobs on both sides of the camera give the Commando somewhat of a symmetrical look. Earlier versions of this camera had a different design for the film advance knob, but as I’ve come to learn this is the second variation of the civilian camera built near the end of Commando production, it has a flat top to the film advance knob on the right.

The Commando shows its military use roots with the focus knob on top of the camera, which functions similarly to the Voigtländer Prominent and Vito III. With the camera to your eye, rotate this knob with your left hand to focus the lens from just under 6 feet to Infinity. A full motion requires a 270 degree rotation which typically requires you to rotate it in several smaller movements, repositioning your fingers each time. The knobs close proximity to the raised middle portion makes it impossible to turn in one motion. Engraved focus distances are upside down when looked at normally but can be read right side up while looking down at the top of the camera.

On the raised portion of the viewfinder is an accessory shoe with the camera’s serial number engraved in the middle. It is interesting to find an accessory shoe on the Ensign Commando as it lacks any obvious flash synchronization and it already has a rangefinder, so the only use for the shoe would be for a meter or a flash system externally triggered by the shutter release. A curiosity of the serial number is that all versions of the Ensign Commando I found online have serial numbers that begin with the letter “C”. If this was a Zeiss-Ikon camera, that letter would be a date code, but that every single version of this camera where I could read the serial number has this letter, I doubt that’s what it is. If anyone knows more about the significance of this “C” in the serial number, please let me know in the comments below.

To the right of the shoe is a small button which is used to open the front of the camera, and to its right is the exposure counter. The exposure counter is linked to the film transport and is additive, showing how many exposures have been made on the current roll, but only when shooting 6cm x 6cm images. The Commando shares another similarity with the Zeiss-Ikon Super Ikonta 530/16 not only in size, but that the exposure counter only goes up to 11 and offers no indicated numbers for shooting the smaller 4.5cm x 6cm images. The reason for displaying numbers only up to eleven on both the Commando and Super Ikonta is that cameras with automatic exposure counters weren’t accurate enough to space the images evenly to guarantee twelve images on a roll of 120. In addition, discrepancies in the exact location of where the film begins and ends on the backing paper meant that getting all twelve images on each roll couldn’t be guaranteed, so these companies just accepted that if you wanted to use the exposure counter, you should only count on eleven. Since the Commando has a window to read the exposure numbers on the backing paper, you can optionally just use that, and get that last exposure back.

On the far right is a very large film advance knob with a tall shutter release above and to the right. The size of the shutter release is a requirement not only to be used with gloves, but also because its location is tightly cramped between the advance knob and top plate. The shutter release had to be tall, otherwise it wouldn’t be usable!

Around back are two sliding doors for reading exposure numbers both for twelve 6×6 images or sixteen 4.5×6 images. While the built in exposure counter on the top plate seems like a nice idea, considering its limitations, I feel as though using the backing paper numbers is the better option. Near the top right corner, immediately below the exposure counter is the round eyepiece for the viewfinder. I normally prefer cameras with viewfinders near the upper left corner, so the upper right location of the Commando’s viewfinder does take some getting used to, but in use isn’t a dealbreaker.

The two sides of the camera are mostly symmetrical both with metal strap loops near the top, but the camera’s left side has a sliding latch for opening the film compartment door. The inclusion of the strap loops is a welcome addition as the weight of the camera would cause a lot of stress on the thin leather straps found on most ever ready cases. A thicker aftermarket strap would be a welcome accessory to the Commando!

The base of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket centrally located in the center of the camera’s mass, flanked on both sides by two small feet which help the camera sit on a flat surface without tipping over. Unlike many roll film cameras where the feet can be pulled down to aide in film loading, the feet on the Commando do not move.

Film transports inside the film compartment from left to right onto standard 120 spools. Like all roll film cameras, an old supply spool can be moved to the other side of the camera and used as the take up spool. Unlike many folding cameras however, there is no way to move the lower post which holds the spool in position, out of the way. Instead, you must lift up on the film advance and focus knobs into a raised position to get the spools in and out. While this works fine, it probably adds complexity which other cameras don’t require.

One of the Commando’s most interesting features is the moving film plane, which in the image to the right is difficult to see. But like the Japanese Mamiya Six, focusing the camera moves the film gate forward and back to change the focus distance. This has the benefit of not having any complex rangefinder coupling from the body to the folding mechanism where the shutter is, and there is no need for a helix or front element focus.

All versions of the Ensign Commando except the earlier Military versions support two different exposure sizes which require hinged baffles built into the film compartment. Unlike many other cameras which rely on a removable baffle, the ones in the Commando can never be lost, and fold into the film chambers on either side. For obvious reasons, this means that you cannot switch exposure sizes with film already loaded into the camera.

The inside of the film door has a large painted metal pressure plate with two holes for the exposure numbers. The Ensign Compando lacks any sort of light seal material either in the door channels or near the hinge. This means that it is not necessary to replace rotted seals, although care should be taken to inspect the condition of the door before shooting a roll of film to ensure no light can leak in.

The Ensign Commando has a self erecting design which means pressing the front door release will open the door and cause the shutter and lens to automatically extend into shooting position. Like most cameras of this type, sometimes the shutter might need a little help getting out all the way, but otherwise should be an uneventful experience. Looking down upon the top of the shutter, a chrome aperture scale has numbers from f/3.5 to f/22 from left to right. Moving the selector also moves a chrome square frame which displays the chosen f/stop. The aperture scale has no click stops. Shutter speeds are changed via a ring around the perimeter of the shutter like any other ring set leaf shutter. Although shutter speeds are engraved in the front face of the shutter, they can still easily be read and are indicated by a red mark next to your selected shutter speed.

A metal lever nestled between the aperture and shutter speed rings is the cocking lever. The Ensign Commando lacks a self-cocking shutter, so this must be done in a separate step. It is very important to remember to cock the shutter before pressing the shutter release as the camera has a double exposure prevention interlock which will prevent you from pressing the shutter release a second time without first advancing the film, should you forget to cock it. In the event this happens, a small manual shutter release button near the lower left strut on the front door can be pressed to engage the shutter release directly on the shutter so that you can recock and fire the shutter without having to advance the film again.

On the front face of the camera, below the film advance knob is a small lever near the bottom of the shutter release which activates and deactivates the exposure counter and automatic film stop feature. To use it, slide the lever to the left and up into a notch which holds it in that position. With the lever activated, turning the film advance knob will advance the film exactly one exposure and engage an interlock when you’ve reached the next exposure, preventing you from overwinding. The exposure counter only works when shooting 6cm x 6cm images as there is no way to recalibrate the counter for the narrower 4.5cm width of the smaller images.

It is very important to remember to cock the shutter first before pressing the shutter release as doing so, will lock the shutter release again until you advance the film, wasting an exposure. This is extra important as pressing the shutter release with the exposure counter lever set, but the shutter not cocked makes a sound similar to what a shutter sounds like when it is firing. This sound could fool you into thinking the shutter is firing, when it is not. If this happens, you must use the manual shutter release button described in the paragraph above to fire the shutter.

Warning: In the event you didn’t read everything I typed above, I’ll give a short warning here to let you know that the Commando requires you to manually cock the shutter before every exposure. A double exposure prevention interlock prevents you from pressing the top shutter release twice in the event you forget to cock the shutter. If this happens, you must press a manual shutter release button near the bottom corner of the shutter, near the edge of the left strut.

The viewfinder has a strong yellow tint with a clear round rangefinder patch in the center. The yellow tint increases contrast between the two windows, making focusing easy as it is the rangefinder patch is very easy to see.

A sliding lever on the front face of the camera, in between the viewfinder and rangefinder window, activates a mask which changes the view from square for 6×6 images to rectangular for 4.5×6 images. This slider is not connected in any way to the baffles inside the film compartment, so changing this mask does not actually change the aspect ratio of the film.

The Ensign Commando is an interesting camera. Although build for the military, it is clear the designers took some design cues and features from other cameras. A little bit of this and a little bit of that, all mixed together in a British melting pot and you have the makings of a pretty cool camera. Like other wartime cameras such as the Kodak Medalist and Premiere Instrument Kardon, this camera was built to withstand extreme use in battle but later sold to the general public as a consumer camera. How does the Ensign Commando stack up against those two worthy cameras? It is time to load in some film and find out!

My Results

Any time I use a camera from a country who also produced film, I like to make an effort to shoot something that is at least close to what would have likely been used in that camera when it was new. In the case of British cameras, I often reach for a roll of some kind of Ilford film, but in the case of the Ensign Commando, I didn’t have any usable Ilford 120 at the time, I went with the next best thing, Kentmere 400. Kentmere isn’t an Ilford film directly, but is made by Harman Technology who also makes current day Ilford film, so since it was close, I went for it. The roll I used expired in 2022, which was close enough so I made the decision to shoot it at box speed. To maximize the number of images I could get from it, I placed the 4.5cm x 6cm baffles in place so I could get sixteen images from my inaugural roll.

I was pleased during my initial tests of the Commando that everything appeared to be in good working order. As far as 65 year old British cameras go, this one was in great shape. I eagerly awaited the results.

First look at the images from the Kentmere 400 test roll were a bit grainier than I had expected. In addition some ink transfer from the backing paper appeared in several shots, most notably the McDonalds image. I’ve always known Kentmere to be an entry level film, often used by students learning photography, so I didn’t have extremely high expectations, but I was a bit disappointed in the results. Perhaps a second roll of some expired Fujicolor Superia 100 film would produce better results. Like the Kentmere, this film was also expired, but I have shot other rolls of this film with good success. For this roll, I set the camera to make square 6×6 images.

As I had hoped, the second roll of color film produced much better images. Sharpness was excellent across the frame with just a tad of softness near the corners and very little vignetting. The colors are a bit off on this roll, which could possibly have been a result of the uncoated optics, but is more likely due to the film being expired by about 20 years.

I could not find any information about the makeup of the 75mm Ensar lens, but with the strong similarities this camera has to other German cameras, I have to imagine the Ensar is likely a 4-element in 3-groups Tessar copy, which makes sense, as the performance is similar to other medium format Tessars I’ve shot. I don’t know that including any kind of higher spec lens would have been worth the additional cost and complexity to develop one, so this lens was a solid choice.

Unlike the first time I shot a Voigtländer Prominent where I struggled to get used to the top focus knob, for the Commando, I quite liked the experience. For someone who has never shot a camera like this, it definitely does take some getting used to as your muscle memory simply doesn’t include the necessary dexterity to focus a lens this way. However, once you get used to it, you can securely hold the camera with your left hand and grip the focus knob with your left index finger and thumb and change focus quite easily.

If there was one characteristic of the camera’s ergonomics that I never really got used to, it was the location of the viewfinder. I am a left eye shooter, and find that shooting cameras in which the viewfinder is on the right side of the camera to be extremely awkward as I have to hold the camera too far to the left of my face. In use, it didn’t affect my ability to get good images, but my instinct each time I raised it to my eye caused my eye to be in the wrong position and I was constantly having to correct it.

I shot one roll each using 4.5×6 and 6×6 images, but left the exposure counter off, relying on the red windows on the back for both rolls. Although I have no reason to believe that the auto stop feature while shooting 6×6 wouldn’t have worked, my previous experiences with features like this on cameras of this era tell me, they’re more trouble than they’re worth. I suspect that users of this camera back when it was new likely felt the same way. I also never encountered an issue with the double exposure prevention feature. I never forgot to cock the shutter before pressing the shutter release, but applaud the designer’s decision to make it so easy to manually press the shutter release directly, if the need ever arose.

Overall, the Ensign Commando is a heck of a camera. I liked the heft of the oversized body, the large knobs meant that advancing the film and focusing the lens were very comfortable and easy, and although I wasn’t wearing gloves while using the camera, I can see how these oversized controls would have been an asset rather than a hindrance. Whether you’re interesting in wartime cameras, British cameras, or just like 6×6 folding cameras, the Ensign Commando has a lot going for it and is worth checking out. Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ensign_Commando

http://www.ensignphotographic.com/commando.htm

https://www.photrio.com/forum/threads/ensign-commando-questions.153832/

Hi,

I have loads of ensign cameras, all the ensar lenses were cooke style triplets the only four element lenses fitted were either zeiss tessars in some of the carbine and 220 autoranges and 420, and the ross xpres lenses fitted to the later 1620s, 1620 autoranges, 1220, 1220 special, 820, 820 special, and not forgetting the horrendously priced 820 autorange. I have had equally good results as yours from my 1620 with a rostar lens, which I think is just an ensar with coating.

Nice to see reviews in America of these lovely English cameras.

I am currently modifying a scrap commando (disintegrated bellows, dislocated apperture leaves, battered body) by fitting a ross express and shutter from a scap 1620 autorange (delamination to rangefinder, bent top cover) new bellows made from shutter material and removal of the double exposure and frame stop/counter. This makes the shutter release a lot lighter and you can’t waste shots . Hoping to get film through it shortly.

King regards,

Tony Boddy