This is a FED 2, a 35mm rangefinder camera made at the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune in Kharkiv, Ukraine during the reign of the Soviet Union between the years 1955 and 1970. The FED 2 was an upgrade to the original FED camera which itself was a copy of the Leica II. Along with a wider rangefinder base, a combined coincident image viewfinder and rangefinder, removable film back, strap lugs, flash synchronization, and a self-timer, the FED 2 was a pretty big upgrade from the original. Like all Soviet Leica “copies”, the FED series offer a compelling alternative to Leica cameras, but without the Leica prices.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 52mm f/2.8 coated Industar-61 4 elements

Lens Mount: M39 Screw (Leica Thread Mount)

Focus: 1m to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Coincident Image Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and PC Sync

Weight: 644 grams (w/ lens), 521 (body only)

Manual: http://www.butkus.org/chinon/russian/fed_2/fed_2.htm

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The FED 2 was the first major redesign of the original “Soviet Leica” built at the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune in Kharkiv, Ukraine in the 1930s. It offers a number of significant improvements to the original design, such as a longer coincident image rangefinder, a removable film back, flash synchronization, adjustable viewfinder diopter, strap lugs, and a self timer. Although the size increased from the original FED camera, it is still a compact and easy to carry camera with good ergonomics and as such is perhaps my favorite Soviet 35mm rangefinder. If you are looking for your first Leica-style camera, but don’t want to pay Leica prices, the FED 2 is a very compelling, and much more affordable alternative. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

December 2019 Update:

This month marks the 5th anniversary of this site’s first camera review. To commemorate this milestone, I’ve gone back and updated some of the site’s very first reviews, including this one for the FED 2. Although that original review contained a lot of great information, my style of writing has changed dramatically over the past 5 years, so what follows is an updated review.

I’ve made significant edits to that first review, leaving only a little of the original information. If you’d like to read the original version, here is an archived copy. This 2019 version has an updated history section, more artwork, all new images of a later FED 2 that I acquired after that original one, and a new gallery.

History

Credit: A large amount of the information that follows comes from the publication, “The Dzerzhinsky Commune: Birth of the Soviet 35mm Camera Industry” by Oscar Fricke, published in the History of Photography Journal, Volume 3, 1979.

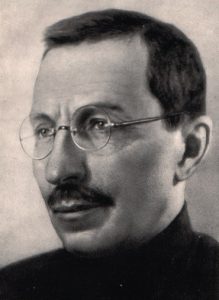

The history of the FED camera is one of the more fascinating stories in all of camera-history-dom involving child labor, Bolsheviks, and a Ukrainian educator named Anton Semyonovich Makarenko.

Makarenko first became a school teacher in the small town of Kryukov, Ukraine in 1905. In 1914, he entered the Poltava Teachers Institute, graduating with honors in 1917, at which time he was appointed the director of his school in Kryukov.

After the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1917, Makarenko became very outspoken in his views on Soviet education. In 1920, the Ukrainian Narkompros (People’s Commissariat of Education) tasked him with creating a colony for the rehabilitation of the growing number of orphaned children, or Besprizorniki. Abandoned and dressed in ragged clothes, the Besprizorniki squatted in slums or roamed the countryside, making a living from crime and begging. Their numbers reached millions by the early 1920s, creating a serious social problem for the Soviet Union which lasted for more than a decade.

Makarenko’s colony was named after Soviet writer, Maxim Gorky as simply the Gorky Colony. Makarenko employed a military-style of regimentation and discipline at the colony in which competition between work groups was encouraged to create a sense of pride, achievement, and community. In addition to education, the students were tasked with some form of productive agricultural work.

Makarenko’s unique blend of military discipline with traditional education was largely a success. He achieved a level of reform not seen at other similar Soviet institutions. Unfortunately, Makarenko’s efforts were not fully appreciated by Ukrainian education officials, who preferred a less military style of leadership, and in 1927 forced him to resign. Later that year, Anton Makarenko was hired by the Ukrainian Police (OGPU) to supervise the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune on the outskirts of Kharkiv.

The commune was named after the Polish immigrant, Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky who in his youth, led a troubled life. Imprisoned a number of times for his revolutionist ideas, in 1917, Dzerzhinsky joined the Bolshevik Party and aimed to organize Polish refugees to fight for freedom in Russia. His activism within the party allowed him to quickly gain notoriety and respect. Eventually elected to the Executive Committee of the Moscow Soviet, Dzerzhinsky earned the respect of Lenin and as a result, in December 1917, appointed Dzerzhinsky as director of a new organization called the “All-Russia Extraordinary Commission to Combat Counter-revolution and Sabotage”, or Cheka for short.

The Cheka was a broad organization whose purpose is far beyond the scope of this article, but in a very simple sense, was an early version of what would become the Soviet KGB. It’s primary purpose was to provide security for the Soviet Union, but in reality, it’s reach extended far beyond that.

In 1920, around the same time Anton Makarenko formed the Gorky Colony, Felix Dzerzhinsky became inspired by the Ukrainian Narkompros’s efforts to remedy the problem of orphaned Besprizorniki and took it upon himself to include the rehabilitation of children to the Cheka’s long list of responsibilities.

As a result, in 1921 the All-Russian Central Executive Committee established the “Commission for the Improvement of the Life of Children”, with Dzerzhinsky as it’s president. This new commission was not well received by members of the Narkompros as they felt that a strong armed government organization was not well equipped to deal with the needs of children.

It would seem their concern was valid, as over the next several years, the numbers of Besprizorniki grew. Homelessness, famine, and illness continued to be a problem in many areas of the Soviet Union.

Felix Dzerzhinsky would pass away from a heart attack after an illness on July 20, 1926. In honor of his contributions, the OGPU decided to build a dedicated children’s commune, to be named the F. E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune in his honor.

The FED commune would open in December 1927 under the leadership of Anton Makarenko whose experience at the Gorky Colony made him an ideal leader. Despite his success at Gorky, Makarenko was often at odds with the Narkompros as they didn’t always support his military style of leadership. This wasn’t a problem at FED. With the full support of the government and a brand new, even lavish facility, Makarenko was freed from the distractions at his former employer.

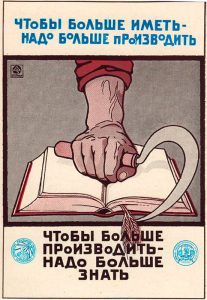

When it first opened, the FED commune contained 150 boys and girls, known as communards, ranging in age from 13 to 17 years old with additional children being added every year. Makarenko’s methods combined productive work and secondary education in a Marxist system of polytechnical education which sought to eliminate the distinction between physical and mental labor. This was accomplished by dividing each day into two four-hour shifts, with one shift devoted to productive work and the other to classroom instruction.

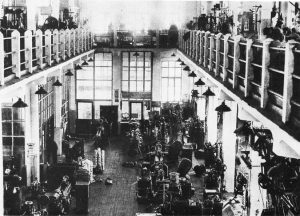

Whereas agricultural labor had been the main emphasis of the Gorky Colony, more complex types of work were developed at the FED Commune. Initially, the commune engaged in handicraft-type productions, with workshops for locksmithing, carpentry, shoemaking, and sewing. Production was started with the aid of outside craftsmen, but as commune members developed their own skills, outside help was reduced to a minimum.

The products themselves, including clothes and crudely-made furniture, initially went to serve the commune’s own needs, but orders were soon accepted from outside as well. In this way, the commune became a completely self-supporting institution and a source of considerable pride.

The value of the daily production rose steadily, and communards received wages which rose as the skill and value of their work increased. The commune even had a marching band and a wide range of clubs, including drama, various sports, photography, and service-type clubs for improving conditions within the commune. The Dzerzhinsky Commune had become a complex community and would soon undertake even greater challenges.

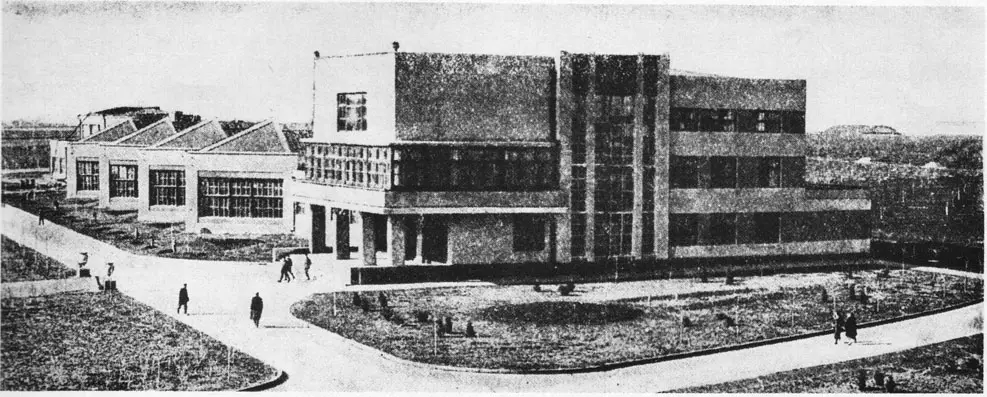

In September 1930, a new worker’s facility of the Kharkiv Engineering Institute was established at the FED commune to bring the communards up to normal university entrance standards. More importantly, the commune decided to construct it’s own full-fledged factory and begin a new industrial phase in it’s life. This undertaking would lay the groundwork and create the experience for an even more ambitious project soon to follow.

Using funds accumulated from the sale of their products, and with the aid of a state loan, a new two-story building was erected for the manufacture of portable electric hand-drills. The communards took an active part in the construction, and the building designed to house the machinery for the manufacture and assembly of the drills as well as additional sleeping quarters, was completed in November.

To cope with the commune’s new activities, the number of communards was increased to 300, now with an average age of between 15 and 20, and including 50 girls. By the end of 1932, the number reached 340, at which point there was one adult for about every four communards. These adults directed the work; they included engineers, technicians, mechanics, instructors, managers, clerks and hired workers who did some of the difficult operations and machinery repairs. Communards participated in all aspects of the production and had the opportunity to learn several different skills.

With the increased capacity of the new FED factory, in June 1932 it was decided that a copy of the Leitz Leica would be built at the FED commune. The need for a quality Soviet made camera meant that the USSR would no longer have to rely on imported cameras from Germany and become even more self-sufficient. On June 21, 1932, a special experimental department for the manufacture of Leicas was established at the commune.

On October 26, 1932, the first three Soviet Leicas were completed. The cameras were exact duplicates of the Leica A, complete with accessory rangefinder. The new cameras were shown in the November 5th issue of the official Soviet government newspaper, Izvestiya. The fact that this announcement was made in such a high profile publication shows the high degree of importance which must have been attached to the event.

The quality of the new Soviet Leicas was praised in the Izvestiya article. The writer enthusiastically claimed that “the Leningrad Optical Institute, having examined the lenses, acknowledged their higher quality in comparison with similar foreign-made lenses”. The 50mm f/3.5 anastigmat lenses of these first cameras were made in Leningrad at the Experimental Factory of the All-Union Optical Industry Association (VOOMP) in cooperation with the State Optical Institute (GOI), also in Leningrad.

The FED commune devoted 1933 to planning and preparing for camera production while the manufacture of electric drills continued at it’s normal pace. The challenge for the commune was a great one as making a Leica was much more demanding than making wooden chairs or even electric drills. With about 300 parts, tolerances to a micron and exacting optics, nothing like the Leica had ever been made in old Russia. New techniques had to be mastered and new equipment had to be made. A detailed production and financial plan was drawn up with considerable help from the State Optical Institute. Construction had begun on a new building to house the factory, with a planned capacity of 30,000 cameras per year.

By 1934, every part of the FED camera, including it’s lenses, was made in the FED factory. The camera was now a copy of the Leica II with it’s integrated rangefinder. From a distance, the only obvious differences (besides the name) between a FED camera and Leica II was the absence of an accessory clip and a different finish. The FED factory struggled to replicate the finish, so early models were painted in a black lacquer. By the end of 1934, a total of 4000 cameras had been made.

Also in 1934, two other Soviet made Leica copies were produced, the VOOMP Pioneer, and the Geodeziya FAG. The VOOMP Pioneer is almost identical in appearance to the FED, but the Geodeziya FAG had minor cosmetic differences such as a rectangular viewfinder window and changes to a couple screw locations. Production of both the Pioneer and FAG cameras were discontinued by early 1935 with only a couple hundred examples ever made. In my research for this article, I could not find any clear reason why these cameras were ever made in the first place.

Over the next few years, the FED camera would receive incremental changes to it’s appearance, lens selection, and improvements to build quality. Reception to the new camera was extremely positive and both solved the problem of not having to rely on imported cameras from Germany, but also to produce something more affordable for photographers to purchase. Demand for the new camera was so high, that photographers began to clamor for needed accessories such as enlargers, developing tanks, slide projectors, and additional lenses.

This demand stressed the capacity of the FED factory far beyond what it’s original purpose was as a rehabilitation center. As a result, changes came to the leadership, and in July 1935 Anton Makarenko was relieved of his duty and transferred to another position in Kyiv. The FED commune’s daily operations continued largely unchanged for the next two years after Makarenko’s departure, but by 1937 the FED factory was turned over to the authority of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD for short, also the successor to the Cheka).

It is unclear how day to day operations might have changed under the NKVD which was a military type organization, but with the FED Commune’s very positive reputation, and the success of the FED camera, it is unlikely that significant changes were made. Workers likely continued to receive salaries and benefitted from other amenities at the factory, but there is no way to be certain.

Production of the FED camera continued over the next couple of years with incremental updates to the original design. Cameras with top 1/1000 shutter speeds and f/2 lenses were produced in 1938 along with a myriad of minor cosmetic updates.

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union and began targeting areas with high concentrations of industry and agriculture like Kharkiv. As German forces advanced, Soviet forces evacuated many industrial enterprises such as the FED factories to safety in Berdsk, beyond the Urals, while demolition teams destroyed much of what could not be moved. On October 25, 1941, Kharkiv fell to the Germans and over the course of the next couple of years, “scorched earth” policies employed by both the Germans and Soviets completely obliterated the FED camera factory and the buildings of the former Dzerzhinsky Commune.

After the war, the Soviet Union began to rebuild it’s optics industry. This period of history is not well documented, and many specific details are not known. Official Soviet figures for camera production show a total of ten cameras produced in 1945, increasing to 5700 in 1946, and 91,500 in 1947, but it’s not clear where these cameras were made. About 1800 special NKAP (Red Flag) cameras were produced in 1946 in honor of the FED workers who had to evacuate their homes during the invasion. These cameras have a special inscription on the top plate which can be seen in the image of the camera to the right.

With the entire FED factory and all of it’s administrative buildings completely destroyed in the war, it is unlikely that a fully operational production facility could have been rebuilt in that short period of time. Perhaps these early post war cameras were all assembled in Berdsk from left over parts from before the factory was destroyed, or perhaps the numbers are simply wrong, we’ll likely never know.

What we do know however, is that in 1947, camera production at the Krasnogorskii Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ for short) factory near Moscow would create their own version of the FED camera called the Zorkiy (iy in Russian, one i in English). Early versions of the Zorkiy were identical to the FED, some even containing both FED and KMZ logos on the camera’s top plate. The only other difference was the inclusion of an updated Industar-22 coated lens.

Full scale production of FED cameras would not resume in Ukraine until 1949, likely after the original factories were rebuilt. For the next 6 years, FED and Zorkiy cameras would be produced concurrently. Although based off the original designs, cameras produced in the KMZ were built both for domestic and export use, whereas FED cameras were largely sold within the Soviet Union. It is said that export Zorkis had a higher build quality, in an effort to show the world that the Soviet Union was a capable force in the optics industry.

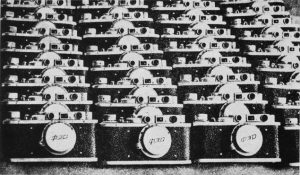

By the mid 1950s with production at full capacity, the design of the FED camera was nearly 20 years old, and it was time for an update. In 1955, a new model called the FED 2 would make it’s debut. The entire body was die cast metal which made it cheaper to manufacture and also made quality control more consistent. The shutter was all new and featured speeds from 1/25 – 1/500 sec and was much more accurate than the original design. The camera’s size increased in every dimension, but with the larger body came significant improvements including a longer 67mm wide coincident image rangefinder, a removable film back, self timer, flash synchronization, strap lugs, a new rewind lever, a threaded shutter release button, and an adjustable diopter, making the camera easier to use for people with poor vision.

The FED 2 was very successful, staying in production until 1970 and selling over 1.6 million copies. A rangefinder-less variant called the Zarya was also produced between 1959 and 1961 which is included in those numbers. As is the case of most Soviet cameras, I could not find any marketing material or anything indicating what it cost. The Soviet economy is very different from anything that exists today, so even if I did find a published price, finding an accurate way of converting it to US dollars would be mostly guesswork.

Since I love to guess, a Leica IIIF with the f/3.5 Elmar collapsible lens sold in a 1956 Montgomery Wards catalog for $177. Considering the FEDs were sold as cheaper alternatives to the Leica, let’s assume a 50% discount compared to a Leica, making a comparable FED $88.50 in 1956 US dollars. If I were to adjust that for inflation, that’s comparable to $840 today which is consistent with what a good quality semi professional camera might cost today.

Screw mount FED cameras would continue to be produced until the 5C in 1990, with the last FED camera, the FED-50 being produced until 1996, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This gives the FED line of cameras the distinction of being one of the first, and longest surviving maker of cameras.

Today, FED is considered to be one of the “big 3” Soviet rangefinder lines along with the Zorki and Kiev. Most FEDs, especially the ones made in the 50s and 60s are very well built, reliable cameras that are capable of great photography more than half a century after they were made. Like many old cameras however, they are not immune to failures due to misuse or simply, the perils of time. While these were generally reliable cameras, finding one in perfect operating condition today, is not always easy, but when you do, the prices are usually quite affordable.

My Thoughts

The FED 2 is one of my favorite Soviet 35mm rangefinder cameras. While there are those who would still consider them to be Leica copies, to see them only in that light does them an injustice. Later models expanded on available shutter speeds, had larger and easier to use viewfinders, and added more advanced features like hotshoes and exposure meters, I like the FED 2 for it’s classic design, excellent optics, and reliable operation.

The top plate shows quite a bit of evolution from the original Leica II that the first FED was based off. The rangefinder base is much longer on this camera, which means the stepped part is also bigger. The rewind knob on the left is basically the same, but underneath has an adjustable diopter which makes looking through the viewfinder much easier for people with glasses or poor vision.

The range of shutter speeds on the FED is more limited than some other FED cameras. The slowest and fastest speeds are 1/30 and 1/500, but the upside to this is that the shutter on the FED 2 is more reliable than many other Soviet cameras with focal plane shutters. While no camera is immune to failure over time, in my experience, FED 2s are more likely to be OK than many other cameras of this era as the lack of a slow speed governor and the tight tolerances needed for the 1/1000 shutter speed means there is less to go wrong. Another benefit to the shutter design on the FED 2, is that compared to many other Soviet cameras, the shutter speeds can be changed with or without the shutter being cocked.

To the right of the shutter speed selector is the threaded shutter release button surrounded by a advance/rewind collar. On this particular example, the Cyrillic letters “B” and “C” (short for Вольно and Cтандарт) are used to indicate rewind and advance, but earlier FED 2s have the Cyrillic letter П (short for Произвольно) to indicate rewind.

Finally, we have the combined film advance knob, film reminder disc, and exposure counter. The film reminder disc has symbols for daylight and tungsten film, and a GOST (ГОСТ) film scale. The GOST scale was used in the Soviet Union at this time and was similar to the ASA scale, but off by a factor of 0.9. For example, GOST 22 and 90 are the same as ASA 25 and 100, respectively.

In the center of the bottom of the camera is a 3/8″ threaded tripod socket. This is larger than the standard 1/4″ size seen on cameras sold in North America, which means if I wanted to use this camera on a tripod, I’d have to get an adapter. On both sides of the bottom are two Leica/Contax style locks for removing the back and bottom of the camera, but also for releasing reloadable metal film cassettes.

One of the biggest upgrades to the FED 2 over the original model is that the camera is no longer a bottom loader. The entire back of the camera is removed for easier film loading. Film transport goes from left to right onto a removable take up spool. Cassette to cassette film transport is possible by using two Leica/Contax style reloadable cassettes.

One thing that didn’t change, nor would it ever over every subsequent FED camera is the M39 screw lens mount shared with the Leica and countless copies. In almost every case (there are exceptions), lenses from the FED 2 can be interchanged between real Leicas and other Leica copies, making the FED 2 an excellent introduction to the system. The earliest FED 2 cameras came with collapsible FED 50/3.5 lenses, but then quickly switched to the Industar-26M. This example is a later variant that came with the Industar-61.

Although the lens mount on the FED 2 is identical to that used on other Japanese and German M39 cameras, one way in which nearly all Soviet M39 cameras differ is in the rangefinder cam that “feels” the focus distance of the lens and moves the rangefinder accordingly. On Leicas and higher quality Leica copies, this feeler has a round wheel on the end of the shaft that spins smoothly as the lens turns. On nearly every Soviet camera with an M39 mount, the feeler is a solid piece of metal with a curved tip. Although this style of feeler generally works fine most of the time, it can fail easier and cause additional friction on the lens while focusing.

On the front of the camera, to the left of the lens mount is the self timer, which does not appear on the earliest FED 2s. It was a mid-model revision somewhere around 1958. When deactivated, the self timer points down, which is opposite of most cameras in which it points up. Rotating the lever clockwise 180 degrees will set it to an approximate 10 second delay when pressing the shutter release.

The viewfinder is predictably small for a 1950s Soviet camera, but with the use of the adjustable diopter seen on the top plate and the bluish-green tinted main viewfinder, composing and focusing images on the FED 2 is surprisingly easy. For someone used to a genuine Leica II or III, the FED 2’s viewfinder would have been seen as an improvement. As a prescription glasses wearer, normally earlier rangefinder cameras are difficult for me to use, and while this camera still isn’t perfect, it’s much more usable than others I’ve tried.

With all the changes to the FED 2 from the original model, it’s size did grow a bit. The FED 2 is wider, taller, thicker, and heavier than the original, but still manages to keep a level of compactness that makes it easy to carry. Later FED 2s would lose the strap lugs, but as far as I can tell, all Vulcanite ones like the one here have them, making them convenient to carry without relying on a leather case.

The FED 2 is a fantastic camera. It offers practical improvements over the original FED such as a wide base coincident image rangefinder, a removable film back, and an adjustable diopter in the viewfinder. It has a simpler shutter that only goes to 1/500 and offers nothing slower than 1/25, but is very reliable and doesn’t exhibit many of the quirks of other Soviet 35mm rangefinder cameras. It supports a huge variety of Soviet M39 lenses, many of which are optically just as good as their German and Japanese counterparts. And it does all of this in a compact, and easy to carry body with terrific ergonomics. What isn’t there to like about the FED 2?

My Results

When I first reviewed the FED 2 in December 2014, it was one of the first 10 classic cameras I had ever shot. I was not used to using entirely mechanical cameras with no light meter. I had barely begun to understand the concept of Sunny 16 and was still new to using rangefinders. My first roll of film was on fresh Fuji 200, a film which would later become my go to film for testing cameras as it’s cheap, predictable, and has a pretty good amount of leniency for exposure errors, which is useful to someone new to film.

The images below are from that first experience, shot in late November 2014 on mostly overcast days and a couple indoor shots.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the rear shutter curtain had several pin-sized holes in the curtain allowing light to expose the film when the shutter was cocked. You can see this heavily in the shot of the pond, and to a lesser degree in the railroad shot. I did not know this until after I got my film back, but basically every shot shows these white orbs of light in the same locations on the frame.

Sadly, that camera had more issues than pinholes as the curtain straps would break halfway through that first roll. The image to the left was taken of my first FED 2 showing one of the curtains sitting loosely at an angle. If you come across any camera with a cloth focal plane shutter and see this, stay away as it will need a shutter curtain replacement.

Of the images I did get, the results were very pleasing. The Industar 26M on that first FED 2 resolved a lot of detail. The shot of the Christmas tree in the gallery above is very sharp and has and excellent colors.

When I first wrote this article, I talked about attempts I made at repairing the curtains of the camera. I ordered some replacement curtains from Fedka which at the time were only $13, and attempted to replace them myself. As I type this in December 2019, replacing curtains is something that is still beyond my capabilities and only shows my naivete back then as I was very much in over my head. The repairs didn’t work, and all I managed to do was create a Ziplock bag of FED 2 parts, which is still in some box somewhere in my basement.

A much easier repair for the broken shutter curtain ribbons on that first FED 2 was simply to buy a new camera and hope it was better, so that’s what I did. Over the next 5 years, I would take that second FED 2 out twice. The first time I would shoot some heavily expired ORWO film (I think it was NP55) and again shooting Fuji 200 again. Here is a gallery of images from those two rolls.

It took me five years to come back and revisit the FED 2, but one thing that immediately struck me was how much I still liked this camera. Reading the original version of this review, I share the same level of adulation as my 5 year younger self and that’s a credit to how good of a camera the FED 2 is. There is a lot more information online about Soviet rangefinders today than there was when I first started this page, and back then, I think there was still a lot of people who weren’t willing to recommend a Soviet camera to someone just getting started out.

The cool thing about coming back to this review is that I can recommend it as a great first film camera because I know someone new to film photography who had a great experience with one, ME!

I’ve certainly handled more capable Soviet cameras like the Zorki 4 with it’s huge viewfinder, the GOMZ Leningrad with it’s prism viewfinder and motorized film transport, and the KMZ Start SLR which was the Soviet Union’s first attempt at a professional system camera, but the FED 2 might still be my favorite. It’s small, easy to use, reliable, and it makes great photographs.

I have never done an A/B comparison between the various lenses that were available on the FED, so whether you have the original collapsible lens, the Industar 26M or the Industar 61, the results will likely be nearly the same. If you need a lens faster than f/2.8, you can swap an f/2 Jupiter 8 from a Zorki or even an f/1.5 Jupiter 3, they’ll all work.

If you’re like I was five years ago, and are interested in old film cameras and want to try a Leica or some other expensive camera, but don’t want to spend the money on one, then maybe you should consider a camera like the FED 2. Leica enthusiasts will tell you that the quality of the two cameras is not the same, and they’re right. Leicas are built to a higher quality than any Soviet camera ever was, but that’s really not the point. To the casual user, you can get 90% of the camera for less than half the cost and that’s a pretty good deal if you ask me!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FED_2

https://sites.google.com/site/fromthefocalplanetoinfinity/fed2

https://funwithcameras.blogspot.com/2020/03/more-gas-from-east-fed-2.html

http://stephenc7.tripod.com/cameras/fed2.htm

http://mattsclassiccameras.com/fed_2.html

http://galactinus.net/vilva/retro/fed-2.html

http://www.fedka.com/Useful_info/Commune_by_Fricke/commune_A.htm

http://www.sovietcams.com/index.php?1073574902

http://aperturepriority.co.nz/fed-2/

http://www.commiecameras.com/sov/35mmrangefindercameras/cameras/fed/index.htm

Hi!

Exactly my experience with my FED-2 but I sent it to Yuriy Marchenko in Ukraine who put it together for USD 50 plus shipping USD 14 to Sweden. Good for me, good for him and good for my dear FED-2! Try [email protected] and say hello from me!

Best regards,

Stefan

Thanks for the reference Stefan! There are several people out there who repair these old cameras, and they all do a great job. I may one day still get mine repaired, or I may just get another FED 2 that has already had a CLA. The shipping two ways to the USA is pretty high. It might be more cost effective to just get another one thats already had the work done. I will update this post if I ever get another.

Very compelling read Mike, you should really be a writing and historian. This was much more detailed than any other account of the FED commune I have read which generally implies a sort of shady cast to the whole enterprise. I have poor eyesight and these are some of the only cameras I can frame and focus with accurately.I just ordered another “Mir” rangefinder so that makes 3 of each. One example of both is inoperative and I haven’t sent them out for service because of shipping as you said. I also have a bunch of Canon rangefinders and they haven’t fared any better, more are broken than working.

Thanks for the kind words, Jon! There’s conflicting info out there about how good the conditions were at the FED plant where these were made, but my article does tend to paint a more positive picture about the working conditions there. I doubt we’ll ever get a true idea of what went on behind the scenes, but I think it’s safe to say, making FED cameras was better than being in a Gulag!

And you touch upon a great point about the working condition of your Canons. It seems that the often recited claim that Soviet cameras were not made with the same quality as their German and Japanese counterparts, my experience today is that Soviet cameras are no more or less likely to have issues today, suggesting that the build quality of them was more on par than many people give them credit for! Sometimes they work, sometimes they don’t, but thats also true of Leicas and Canons too!

I appreciate your reviews, and find them to be of a high standard and educational. However, I found it too difficult to read much of this one due to the “bubbles” flying around over the screen. It was much like trying to read a book with a distracting fly whizzing in front of you.

Maybe it is just me affected this way and others may love the effect, so please take this comment as one kindly meant as I much prefer giving praise.

Arnold, thanks for the feedback both on the review and my falling snow effect! It’s just something I enabled for Christmas. Don’t worry, it wont be permanent, as I’ll probably disable it around the 26th or so. If it helps, it’s only enabled on desktop browsers, and shouldn’t show on mobile phones or tablets.

Great post, the most comprehensive I’ve seen so far! It actually motivates me to try my grandfather’s FED-3 (and maybe someday I’ll buy FED-2). Greetings from Ukraine 🙂

I consider my Fed-2 to be one of my favorites in my collection. Mine has the Industar 26m lens and I have taken some decent photos with it. I had to repair some holes on the shutter curtain but after that it worked like a charm.

Thanks for the in-depth review and history.